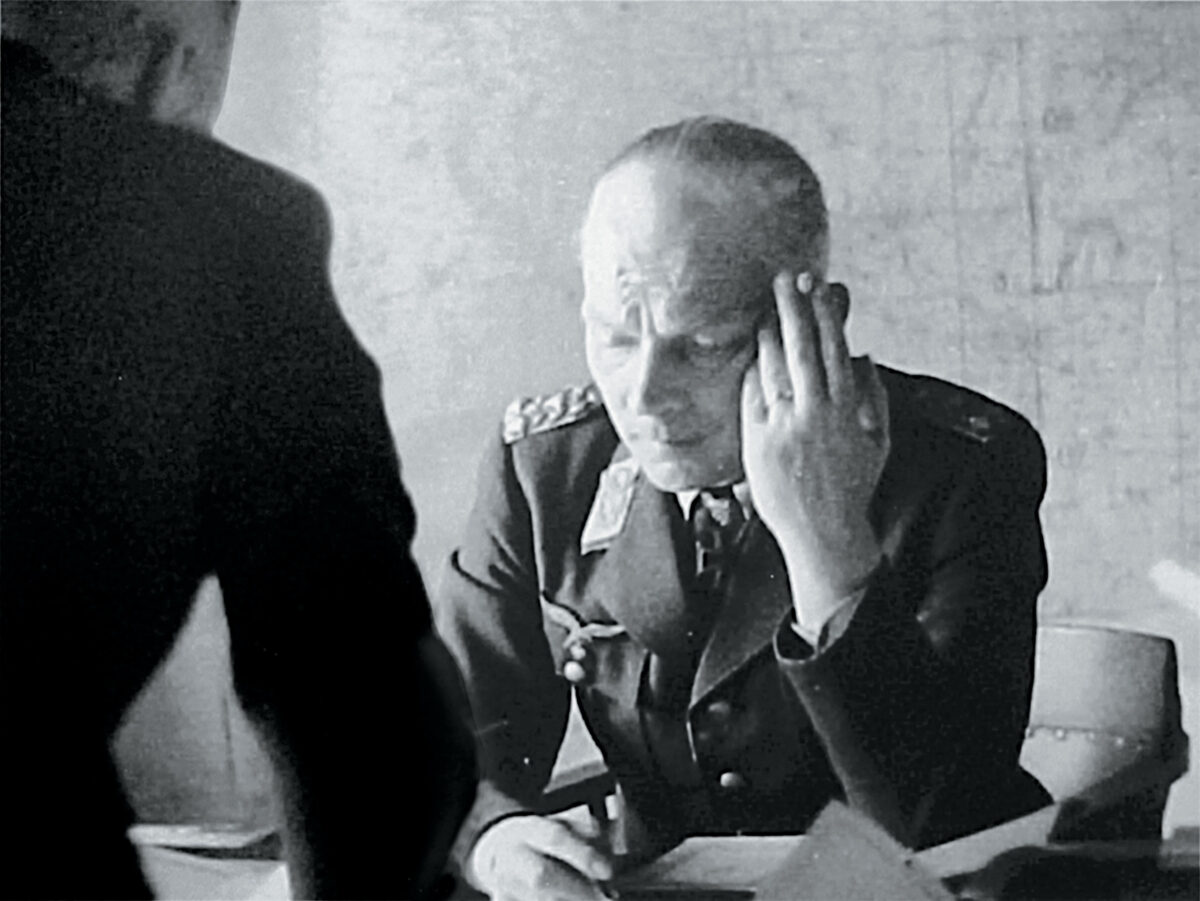

Richthofen became known as ‘the Tartar’ for combining cold-blooded ruthlessness with ingenuity in directing operations

April 21, 1918, remains one of the best-known days in aviation history. It was the day that the Red Baron, Manfred von Richthofen, the top ace of World War I, was shot down and killed after leading the fighter wing he commanded into combat. By coincidence, it was also the first time in aerial combat for his younger cousin, Baron Wolfram von Richthofen, who had recently been assigned to the same fighter wing, the famous Jagdgeschwader I.

Manfred’s deadly dogfight over northern France that day is probably the most famous single battle in the history of air warfare. The Red Baron has long been regarded as a fascinating and romantic figure, with his exploits featured in dozens of books and several films. Yet it was the lesser-known Richthofen, who barely survived his first day in combat, who would go on to have the far greater impact on aerial warfare.

The contrast between the two is striking. Manfred von Richthofen is viewed by many as a throwback to an older form of individualistic warfare, someone who fought as a “knight of the air.” His cousin, on the other hand, represented a new breed of technocrat warrior. Armed with a Ph.D. in aeronautical engineering, Wolfram von Richthofen was behind the development and manufacture of many of the aircraft that equipped the Luftwaffe in World War II. As a commander on several fronts, from Spain to Poland to Russia, he played a leading role in shaping modern tactical air power and making it a decisive force on the battlefield. First in Poland in 1939 and then in France in 1940 he inserted the Luftwaffe into the German blitzkrieg tactics that astonished the world. One of Hitler’s favorite generals, Richthofen was made a field marshal in 1943 at the relatively youthful age of forty-seven. No less an authority than Field Marshal Erich von Manstein deemed him “the most outstanding air force leader we had in World War II.”

Wolfram von Richthofen hailed from a large clan of landed aristocracy that settled in Upper Silesia, today part of Poland. Like many Richthofens before him—including his cousin Manfred—he chose the army as a career. Shortly before his nineteenth birthday in 1914, Wolfram was commissioned into a Prussian cavalry regiment, the 4th Silesian Hussars. He led a platoon into combat in August 1914, where his cool display of leadership under fire in the war’s first battles earned him an Iron Cross. In the fall, his cavalry regiment moved to the eastern front, where he saw considerable action through 1915. But as the war settled into the trenches, there was little for the cavalry to do. For an ambitious officer hoping to make his mark, it was an unbearable situation.

Manfred von Richthofen and his brother Lothar had abandoned the cavalry by this time, transferring to the Imperial Air Service in 1915. In 1917, Wolfram followed his cousins’ example, showing enough aptitude to be selected for the fighter arm. He arrived at his famous cousin’s wing in early April 1918. Lucky to survive the dogfight that killed Manfred, Wolfram went on to demonstrate the Richthofen killer instinct by shooting down eight Allied planes.

Richthofen hoped to stay with the air force after the war’s end, but the Treaty of Versailles abolished it and reduced the army to a small, 100,000-man force. So he left the army and earned a degree in aeronautical engineering at the Technical University of Hanover, one of Germany’s top engineering schools.

The German army after World War I was led by visionary general Hans von Seeckt, who turned the small army allowed by the Versailles treaty into an elite cadre to serve as a foundation for a large and modern force. Because he believed that air power would play a central role in future wars, von Seeckt ensured that a small, secret air force was camouflaged within the army. He also insisted that Reichswehr officers master the new technologies of war and established a program to send officers to earn engineering degrees in preparation for joining the army’s general staff. As a flier, qualified engineer, and decorated combat veteran, Wolfram von Richthofen was an ideal candidate to join the secret air staff. He was invited to rejoin the army in 1924 after completing his studies.

The general staff put Richthofen’s talents to use. He served as a liaison between the shadow air staff and German aviation firms, and studied how the German aircraft industry could be best employed for rapid mobilization. He also deepened his expertise. In 1929 he was awarded a doctorate in engineering from the University of Berlin; his doctoral thesis was a top-secret study on production techniques for building all-metal aircraft. It would become the foundation for the first expansion plans of the shadow Luftwaffe in 1932–1934.

Like most of the officer corps, Richthofen believed that Germany needed strong, authoritarian leadership and welcomed Hitler’s assumption of power in 1933. He was never a member of the Nazi Party because German military regulations barred officers from any political party membership or activity. Nonetheless, Richthofen was soon known as one of the more enthusiastic admirers of Hitler within the officer corps.

With the start of rearmament in 1933 Richthofen was appointed chief of aircraft development at the Luftwaffe’s Technical Office. Working with the head of that office, Col. Wilhelm Wimmer, whom Richthofen called “the best technical mind in the Luftwaffe,” he spent three happy years supervising aircraft testing and development. With ample funding from a Nazi government in a hurry to rearm, he assigned contracts to German aircraft designers and manufacturers to develop a new generation of fighters and bombers that would outperform the aircraft of Germany’s likely enemies. Under his supervision, the superb Bf 109 fighter and the He 111 and Do 17 bombers went from the drawing board to factory production in less than three years—a remarkable achievement.

Ironically, Richthofen was initially opposed to the procurement of an aircraft that would go on to perform brilliantly in the first half of the war, the Ju 87 Stuka dive-bomber, because he believed dive-bombers were too vulnerable to antiaircraft fire. However, he strongly supported the development of heavy strategic bombers and saw that two prototype four-engine bombers, the Do 19 and Ju 89, were ready for testing by mid-1936. Richthofen was disappointed when the heavy bomber program was cancelled, believing that these weapons should have top priority and presciently predicting in September 1939 that “Germany will regret going to war without heavy bombers.”

Richthofen, the Ph.D. engineer, thought far beyond the immediate requirements of the Luftwaffe. He believed the time was not far off when air forces would be equipped with rockets and high-altitude rocket planes. In 1934 and 1935 he provided Luftwaffe support for Wernher von Braun’s rocket research. The

jet impulse engine that became the engine for the V-1 rocket began with a contract issued by Richthofen. In 1935 Richthofen pushed the development of a high-altitude rocket plane that could operate at over fifty thousand feet. The eventual result was the Me 163 Komet rocket fighter.

In the summer of 1936, the Luftwaffe’s commander in chief, Hermann Göring, replaced the exceptionally capable Wimmer with an incompentent crony, Ernst Udet, and Richthofen quickly became disenchanted with his job. Udet soon put the Luftwaffe’s aircraft development programs into a muddle by insisting that bombers under development, such as the promising Ju 88 “fast bomber,” be completely redesigned as dive-bombers. An appalled Richthofen remarked, “This is nonsense, you can’t go against nature!” Udet’s decisions pushed the Luftwaffe’s development back by years, and Richthofen sought a command position elsewhere. He did not have to wait long.

In July 1936 civil war broke out in Spain, and Hitler decided to intervene on the side of Gen. Francisco Franco’s conservative Nationalists. The Luftwaffe deployed a force of one hundred aircraft, flak guns, and five thousand men to Spain. This force, known as the Condor Legion, provided Germany with an opportunity to test its new weapons and gain experience in modern warfare. Maj. Gen. Hugo Sperrle was named the Condor Legion’s commander; Richthofen, now promoted to lieutenant colonel, became his chief of staff. Richthofen directed the daily operations of the force—and seized the chance to prove his abilities as a senior officer in battle.

During the first major German operations in Spain in early 1937, Richthofen insisted on thorough planning and worked his staff long hours. He spent much of his time at the front conferring with the ground commanders in order to thoroughly understand their plans and air support requirements. Richthofen was determined to prove that air power could be decisive in battle, and he was ready to develop new tactics to do it.

During the Nationalist offensive into the Basque region in the spring of 1937, Richthofen noted that the Nationalists were deficient in artillery. Since the Condor Legion was equipped with several batteries of superb 88mm antiaircraft guns, he deployed them on the front lines as artillery pieces. The guns proved highly successful in knocking out Basque fortifications and enabling the Nationalists to advance. Richthofen gleefully noted that his new tactics had “caused consternation among the flak theorists back in Berlin,” who were shocked to see the antiaircraft gun used as an artillery piece. But using it in ground combat became standard Wehrmacht doctrine.

Richthofen became known among Condor Legion staff as “The Tartar” for combining a cold-blooded ruthlessness with ingenuity in directing operations. He devised, for example, new methods of using bombers and fighters as “flying artillery” on the front lines to destroy Basque defenses. Sperrle and Richthofen would sit on a hilltop overlooking the front lines and guide the aircraft to their targets over the radio. Such accurate air support allowed the Nationalist army to maintain its advance, and it overran the entire Basque province in several weeks.

Richthofen’s traits were combined to devastating effect in an attack that became infamous for its brutality: the bombing of the small Basque town of Guernica on April 26, 1937. German and Italian bombers dropped thirty-one tons of munitions on the town that day, killing hundreds of people and destroying nearly three-quarters of its buildings; this was one of the first instances of a city being destroyed by aerial attack and a precursor to even more destructive attacks made later in the war. After Guernica fell, Richthofen drove through the wreckage, laconically noting that “the town was leveled and closed to traffic for twenty-four hours.” His most enthusiastic diary entry that day was reserved for the new German equipment that had just been tested there: “The 250-kilogram bombs and EC B 1 bomb fuses worked wonderfully!”

In early 1938 Richthofen returned to Germany to be promoted to colonel and take command of a bomber wing. He was back in Spain in November, now as a major general in command of the Condor Legion, and directed the air support for the final Nationalist offensive in early 1939. After the Nationalist victory in March, Richthofen returned to Germany as a national hero. In June, he and Sperrle led the troops of the Condor Legion in a triumphal parade through Berlin, where Hitler lauded the assembled fourteen thousand veterans for “teaching a lesson to our enemies.”

But the most important lesson learned in Spain was by the Germans. The experience they gained there had a huge influence on the tactics of the newly revitalized Luftwaffe and put Germany well ahead of the Western Allies in modern war experience. The war had made it clear that the effective cooperation of air and ground forces was the key to victory. As a result, in the summer of 1939 the Luftwaffe formed the “Special Purpose Division,” a force of three-hundred-plus aircraft composed of Ju 87 Stukas, Henschel attack planes, a reconnaissance squad-ron, and fighter groups for escort. It was organized specifically for the close support of ground forces, and placed under Richthofen’s command. Its first deployment? Poland.

In many respects Richthofen’s use of air power in the Polish campaign of 1939 followed a traditional German approach to combat, which involved massing forces to support the main effort. For the first ten days of the Polish campaign, Richthofen’s Stukas and attack planes flew four to six sorties a day, operating from rough forward airfields and supplied with fuel and bombs by the mobile logistics columns. As in Spain, Stukas and bombers pummeled the Polish fortifications. However, most Luftwaffe attacks were concentrated behind the front lines and sought to paralyze Polish troop movement.

In order to observe the situation on the ground, Richthofen flew himself around the battlefield in a Fi 156 Storch reconnaissance plane. On several occasions he spotted targets; on another, he landed at a panzer division’s forward command post to personally coordinate air support to stop a Polish counterattack.

In less than a month it was all over. With relatively few losses, Richthofen’s airmen had performed brilliantly. Luftwaffe close air support not only brought the campaign to a speedy conclusion, but saved thousands of soldiers’ lives by destroying Polish fortifications that otherwise would have required a costly ground assault. Gen. Walther von Reichenau, commander of the main panzer forces in the campaign, declared that the Special Purpose Division had “led to the decision of the battlefield.” The Germans’ experience in Poland proved that their conception of joint operations could work. The division was enlarged and renamed the VIII Fliegerkorps (Air Corps).

The VIII Fliegerkorps moved to the western front in October 1939. Richthofen relentlessly drove his staff and commanders through a series of war games and exercises to prepare for the next campaign. He absorbed lessons learned in Poland and revised the Luftwaffe’s tactics. In his view, the greatest problem in the Polish campaign had been army/air force communications. So additional Luftwaffe ground liaison teams were trained and placed in army corps headquarters and with the panzer and motorized divisions. When the Germans began their offensive into France in May 1940, the VIII Fliegerkorps was the best-trained tactical air force in the world.

In the first week, Richthofen’s air corps of more than three hundred Stukas, bombers, and escort fighters devastated Allied airfields and supported the advance of the German armies through the Low Countries. At the same time, the main German armored force, concentrated in Gen. Paul Ludwig Ewald von Kleist’s Panzergruppe, broke through the French defense line at Sedan and crossed the Meuse River. The way was open to advance to the English Channel and separate the Allied northern army group from the rest of the Allied armies.

Von Kleist had advanced so rapidly, however, that the slow-moving infantry divisions meant to protect his flank had fallen far behind; on May 16 they were told to slow their advance. At a commanders’ conference that day, Richthofen demonstrated his operational savvy, telling Göring that von Kleist had a war-winning opportunity, but that it was fleeting and that delay would allow the Allies to organize new defenses. Göring directed the VIII Fliegerkorps to “follow Panzer Group von Kleist to the sea.”

Richthofen ordered his forces to screen and protect Panzer-gruppe von Kleist’s open flanks and to execute attacks in front of the panzer advance. Reconnaissance units of the VIII Fliegerkorps spotted French divisions moving to counterattack and relentlessly bombed troop columns, as well as French tank units that appeared on the German flanks. Richthofen’s Stukas helped repel attacks by Col. Charles de Gaulle’s 4th Armored Division at Montcornet on May 17, and at Crécy-sur-Serre on May 19. The VIII Fliegerkorps attacks threw the French and British forces into confusion. The Luftwaffe provided the infantry divisions with just enough time to move up and protect the Panzer-gruppe’s flanks. On May 20, von Kleist’s force reached the English Channel and divided the Allied armies.

The campaign of 1940 was a dramatic example of how air power could play a decisive role in maneuver warfare. Richthofen had proved himself to be one of the Wehrmacht’s coolest and boldest senior commanders. When others worried that contact reports from the front indicated major Allied counterattacks, Richthofen correctly discounted them as “panic reports.” He complained, quite accurately, that most of the army and air force generals were reluctant to take full advantage of their operational opportunities: “This nervousness, worry about flanks and various fears seem to be the natural approach to operations for the higher leadership.”

In acknowledgment of Richthofen’s key role in the victory, he was awarded the Knight’s Cross and jumped two ranks to General der Flieger.

Moving to Normandy, Richthofen reorganized his forces for the Battle of Britain. The first phase, which consisted of attacking British shipping in the English Channel, was another success for the VIII Flieger-korps, which consisted mostly of Stukas. But the next phase, the air battle over Britain itself, was a disaster. While the Stukas survived far better against antiaircraft fire than Richthofen had predicted, they were still easy prey for Allied fighters. In attacks against the RAF airfields in southern England, Richthofen’s Stukas took such heavy losses from RAF fighters that they were quickly pulled from the battle.

Over the next several months Richthofen rebuilt his force. In early 1941 he was ordered to Bulgaria to support the German army’s attack into Greece. In a three-week campaign his air corps enabled the German Twelfth Army to rapidly overrun Greece; they also inflicted heavy losses on Allied shipping. In the Greece and Crete campaigns, the Royal Navy lost four cruisers and eight destroyers to Luftwaffe attacks; dozens of merchantmen and transports were also sunk. But while Richthofen had another blitzkrieg victory to his credit, he had no time to rest. The invasion of Russia was about to begin and his air corps was needed to support Army Group Center’s advance towards Moscow.

By now, the Germans believed they had perfected the blitzkrieg style of warfare. In the first weeks of battle, Richthofen’s air corps destroyed thousands of Soviet aircraft on the ground. With complete air superiority, the VIII Fliegerkorps attacked Russian transportation and destroyed Russian fortifications. Encircled Russian armies, like those at Smolensk, were superb targets for the German airmen.

Richthofen continued to develop new tactics for his forces. Luftwaffe personnel in armored vehicles on the front lines controlled air strikes just in front of German troops. Luftwaffe support improved dramatically in accuracy and effectiveness, while friendly fire incidents were reduced. Throughout the summer and fall of 1941 Richthofen’s force shifted between the northern and central fronts, always supporting the main effort of the advance. By November 1941 the VIII Fliegerkorps was at the gates of Moscow with victory in sight.

However, the fundamental weaknesses of the Wehrmacht played a key part in sparing Moscow. Deep into Russia, front line units ran out of fuel and parts. By November 1941 the panzer divisions were at a fraction of their strength because most of their tanks and motor vehicles had broken down. It was a similar story for the Luftwaffe: only 20 percent of Richthofen’s aircraft were operational.

While snow and bitter cold hampered operations, the Germans had also underestimated the Russians’ ability to replace their colossal losses. On December 6, dozens of fresh, well-equipped Russian divisions hit the Germans outside Moscow in a surprise counteroffensive. As the Germans reeled back, Richthofen used his handful of flyable planes in a campaign that gave the army time to sort out new defenses.

The main German effort next shifted to the south, where they planned to drive all the way to Russia’s main oil fields at Baku. But first, the Germans needed to eliminate the Russian armies on the flank in the Crimea. The commanders selected to lead this operation were Gen. Erich von Manstein, commander of the Eleventh Army, and Wolfram von Richthofen, now a colonel general.

The two generals met in the spring of 1942 and immediately found common ground. Richthofen noted that Manstein, unlike other senior army generals, was “surprisingly mellow and accommodating. He understood everything. It was completely uplifting.” Manstein remarked that the strong and accurate air support from Richthofen’s units “pulled the infantry forward” through successive Russian defense lines with relatively low losses. For the next year, the two men would form one of the most productive command partnerships of the war.

By the end of June, Russian resistance was broken and ninety thousand troops surrendered at Sevastopol. But Richthofen had little time to celebrate his latest triumph. He was now given command of the Fourth Luftflotte (Air Fleet)—the entire Luftwaffe force in southern Russia. With the Crimea in German hands, the plan was to make a two-pronged offensive: to the south into the Caucasus toward Baku, and on the northern flank to Stalingrad and the Volga. With Luftwaffe support, the German army advanced rapidly as the Russians retreated. By August they had driven hundreds of miles, encountering serious resistance only from the Russians defending Stalingrad.

But the weaknesses of the German war machine again became evident. By 1942 Germany was losing the production battle, and aircraft manufacturing barely kept up with losses. The Luftwaffe training programs had not expanded enough and the air force faced a shortage of pilots and aircrew. The supply system barely worked, and Fourth Luftflotte units became short of planes, fuel, and parts as the advance continued. When the offensive started in July, Richthofen had only five hundred operational aircraft to cover a vast region; by fall he had perhaps half that many.

In the meantime, the German Sixth Army was bogged down in street fighting in Stalingrad and a whole army group was stuck in the foothills of the Caucasus. The thinness of the German front gave the Soviets a perfect opportunity to counterattack. In November Russian armies broke through the German lines north and south of Stalingrad and moved to encircle the two hundred fifty thousand men in Stalingrad. The sensible solution was to pull the Sixth Army out of Stalingrad immediately. But Hitler disliked giving up ground, and Göring promised the führer that the Luftwaffe could supply the trapped Sixth Army by air. Without consulting Richthofen, the decision to keep the Sixth Army in Stalingrad was made.

When he received the order to mount an airlift, Richthofen was virtually in a state of shock. There was no way that the Luftwaffe’s small transport force could do the job. As he went to confer with Manstein a staff officer heard him mutter, “Impossible…even to imagine such a thing….”

Battling bad weather and a strong Soviet fighter force, Richthofen tried to supply the army in Stalingrad. But failure was inevitable. On February 2, 1943, the Sixth Army surrendered. Meanwhile, Manstein and Richthofen managed to restore the front and slow the Soviet advance. A few weeks after the Stalingrad debacle the Germans struck back at the Russians, inflicting heavy losses and retaking Kharkov. On February 16, in recognition of his superb leadership in several campaigns, Hitler promoted Richthofen to the rank of field marshal.

Richthofen hoped to support Manstein’s forces in the planned offensive at Kursk, but a crisis in the Mediterranean now intervened. With the surrender of the Axis armies in Tunisia in May 1943, it was clear that Sicily was the next Allied target. And if the Allies landed in Sicily, the Italians would probably abandon their alliance with Germany. In mid-June Richthofen was ordered to Italy to take command of the Second Luftflotte.

He faced a nearly hopeless situation. By early July the Axis air forces in Italy were outnumbered five to one by the British and the Americans, and the German airfields in Sicily were so badly battered by Allied bombers that Luftwaffe attack units could barely operate. Richthofen had only one strategy to defend Sicily: “We can put every effort into attacking enemy shipping…if we are successful in disrupting the supply over the beaches we can make his ground units ineffective and vulnerable to counterattack by our forces.” Always the realist, Richthofen noted, “We can’t predict success with this strategy…but it’s the only strategy that offers a possibility of success.”

When the Allies landed in Sicily on July 10, 1943, Richthofen’s airmen made their best effort against the massive landing fleet, but they had little success in the face of superior Allied air and naval power. In several days of attacks, the Luftwaffe sank only fourteen supply ships and two destroyers—not enough to delay the Allies. The Luftwaffe retreated to the Italian mainland to await the next Allied landings.

When the Allies landed on the mainland in September, Richthofen expected to do better, as he had a dangerous new weapon to use against them. The Germans had developed two models of a guided bomb that could be dropped from twenty thousand feet, miles from the target, and be guided to it by radio-controlled tail surfaces. These were the first true “smart bombs” and the Salerno campaign was their first major test. Because of the Allied air superiority, Richthofen ordered the bombers carrying the guided bombs to attack at night.

In less than a week, they had badly damaged the cruiser USS Savannah, crippled the cruiser HMS Uganda, and disabled the battleship HMS Warspite, which had been providing gunfire support for Allied units ashore. It was an auspicious beginning for the guided bomb in warfare, but the bombs were difficult to use, and only a handful of aircrews knew how to deploy them.

Richthofen continued to ferret out other ways to inflict maximum damage. One opportunity arose at the port of Bari in southern Italy, where he noted a weakness in Allied air defenses. Through November 1943, Luftwaffe reconnaissance planes kept Bari and its shipping under careful observation. Then, in a raid meticulously planned by Richthofen, a force of 105 Ju 88s—virtually every Luftwaffe bomber in the Italian theater—attacked Bari harbor the night of December 2.

Richthofen’s tactics were superb. Most bombers first flew out to sea and dropped to low altitude to avoid Allied radar observation. Pathfinder bombers dropped aluminum foil strips to jam the Allied air defense radar, while the bombers systematically worked the port over by the light of parachute flares.

The port was crammed with shipping, and the Ju 88s hit an ammunition ship and a tanker. The ship blew up, raining explosives on the other vessels as fire from the tanker’s burning oil spread. Sixteen Allied merchant vessels were destroyed and eight others damaged. The port facilities were knocked out of operation for three weeks. Naval historian Samuel Morison described it as “the most destructive air attack since Pearl Harbor.”

Yet the raid could not be repeated elsewhere; Allied antiaircraft and night fighter defenses at other ports were too strong for the Luftwaffe’s small bomber force. Richthofen next attempted to stop the Allied landings at Anzio in January 1944. But by then the Allies had developed effective countermeasures to the guided bombs and the Luftwaffe attacks were ineffectual. By the spring of 1944, the Luftwaffe in Italy was mainly a defensive fighter force, with most of the air units withdrawn to defend the Reich. Richthofen had little left to command.

Richthofen’s end came quickly, and from an unexpected direction. In late 1944 he was diagnosed with a brain tumor. After two unsuccessful operations, he was relieved of command in November and sent to the Luftwaffe hospital in Bad Ischl, Austria. He died there as an American prisoner in July 1945 at age forty-nine, a few weeks after General Patton’s Third Army occupied the area.

By then, Richthofen had played no real role in the war for more than a year. But for pioneering—in Spain, Poland, Russia, and Italy—many of the air support doctrines and tactics that became standard in modern warfare; for his numerous contributions to aviation technology; and, primarily, in France in May 1940, for revolutionizing the role of air power in warfare by making the air force an equal partner with the army, he created a legacy that would have a much more lasting influence than that of his far more famous cousin, the Red Baron.

This article originally appeared in the August/September 2008 issue of World War II magazine.