The future Spanish dictator’s brother blazed a trail across the South Atlantic but failed to attain his ultimate goal of a round-the-world flight.

Early on January 22, 1926, the Spanish air force Dornier J Wal flying boat Plus Ultra swooped low in salute around the Christopher Columbus monument at Huelva in southwest Spain. Minutes earlier, it had taken off from the Rio Tinto at Palos de Moguer, upstream from Palos de la Frontera, where on August 3, 1492, the great Genoan seafarer had embarked on his first voyage of discovery.

Unlike Columbus, Plus Ultra then set course for West Africa, its ultimate objective being to cross the South Atlantic to Brazil and then to fly down the east coast of South America to Buenos Aires, Argentina. Apart from linking two Spanish-speaking countries by air, the flight was intended to bolster Spain’s prestige in the world of aviation at a time when it had no aircraft manufacturing industry of its own. Initially, the flying boat would follow the route taken by the Portuguese aviators Sacadura Cabral and Gago Coutinho in their 1922 first airplane crossing of the South Atlantic in stages, using three Fairey IIID floatplanes (see “Forgotten Transatlantic Odyssey,” May 2015).

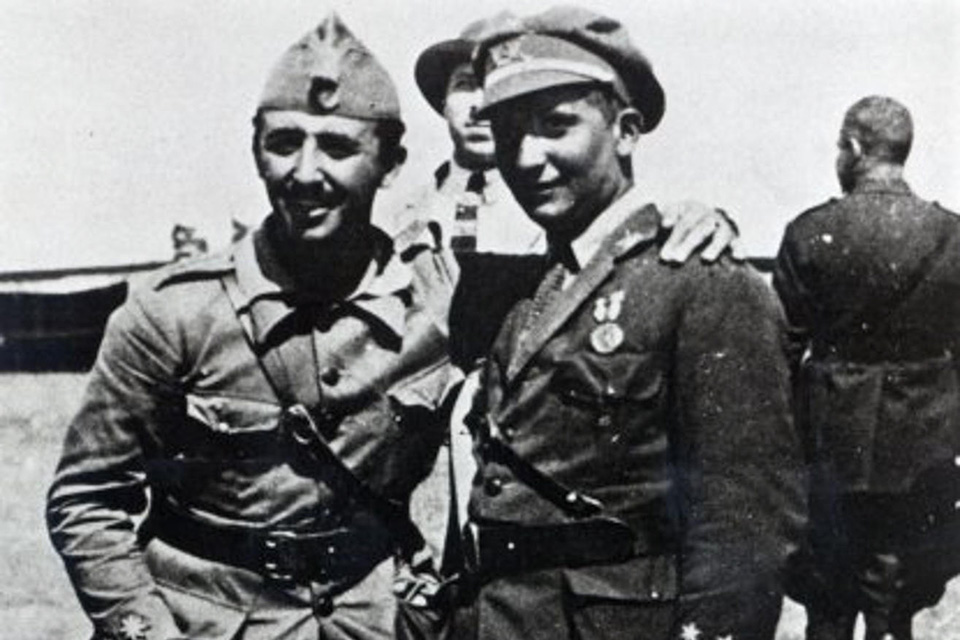

At the Dornier’s controls was pilot Major Ramon Franco Bahamonde, the prime mover of the flight. Captain Julio Ruiz de Alda Miqueleiz served as the copilot/navigator, naval Lieutenant Juan Manuel Duran Gonzalez was the second copilot and Pablo Rada Ustarroz the mechanic.

Ramon Franco was the youngest of three brothers, the second of whom, Francisco, would go on to become generalissimo and dictator of Spain from 1939 to 1975. After attending a military academy, Ramon served from 1914 as an infantry officer in Spanish Morocco during the conflict between colonial forces and Berber tribesmen from the Rif Mountains. In 1920 he transferred to the Spanish air force, the Ejercito del Aire (Army of the Air), later flying as a military aviator in Morocco.

The open-cockpit Dornier J Wal (Whale) Plus Ultra (Farther Still) had been specially adapted for the South Atlantic flight, including the installation of two 450-hp Napier Lion V engines mounted back-to-back in tandem, driving four-bladed propellers in a nacelle above the fuselage. The aircraft had been fitted with a Marconi AD6 telephone transmitter and a Marconi Type 14 direction-finder as extra navigational aids. Marconi had also arranged with its affiliated companies in South America to keep in touch with the flying boat as it approached the South American mainland and during its flight down the continent’s eastern seaboard.

First flown in 1922, the Wal introduced the classic Dornier flying boat configuration featuring a two-step hull and a strut-braced parasol wing. Stubby sponsons protruded from the fuselage below the wing to improve stability on the water and add extra lift in flight. Due to the punitive terms of the Versailles agreement, no production could be undertaken at Dornier’s German works at Friedrichshafen. So Dornier set up a subsidiary factory at Pisa, Italy, where up to 150 Wals were made. Franco’s Wal was assembled there under his close personal supervision.

After departing Palos de Moguer on January 22, bound for Las Palmas, Canary Isles, Franco and his crew completed the relatively uneventful 806-mile flight in eight hours. Minor repairs delayed Plus Ultra’s departure from Las Palmas until the 26th, when they took off on the 1,081-mile leg southward to Porto Praia in the Cape Verde Islands. This was accomplished in nine hours and 50 minutes. Although visibility was poor, the Marconi direction-finding equipment worked perfectly, providing an accurate fix on their destination.

Several days in Porto Praia were spent lightening Plus Ultra for the long transatlantic leg. To ensure that maximum fuel could be carried, any unnecessary items were offloaded. So too was Lieutenant Duran, who disembarked to board the destroyer Alsedo, which sailed almost immediately for the flight’s next destination, the Brazilian archipelago of Fernando de Noronha. Meanwhile, the cruiser Blas de Leso, loaded with spares and other equipment, waited to act as Plus Ultra’s guardian angel.

Unfavorable weather around Porto Praia on January 30 led Franco to alter their departure point to the more sheltered Barrera de Inferno, from where they eventually took off at 0611 hours. Most of the 12-hour, 1,429-mile flight was made at 1,000 feet, flitting between the clouds over a turbulent sea. Plus Ultra was out of wireless contact for four hours, but eventually they picked up Recife on the Brazilian mainland. Shortly before sunset they glimpsed Fernando de Noronha.

The sea was extremely rough, and to the assembled observers Plus Ultra initially seemed intent on overflying the islands and pressing on to Recife. It soon turned back and, in Franco’s capable hands, touched down safely amid the churning waves. The crew immediately requested fuel and assistance, but the atrocious weather and the fading light made it impossible for any boats from Fernando de Noronha to reach them, or for the flying boat to dock alongside.

At last, after several frustrating attempts, they were able to anchor, after which they spent an uncomfortable and very damp night on board. Adding to their woes, one of the propellers was damaged by the waves. Notwithstanding, they had just completed the second longest airplane flight to date (after John Alcock and Arthur Brown’s 1,890-mile transatlantic crossing in a Vickers Vimy on June 14-15, 1919), becoming the first aviators to cross the South Atlantic using only one aircraft.

The next day, January 31, Alsedo arrived with the Wal’s equipment and Lieutenant Duran rejoined the crew. After refueling, Franco took Plus Ultra into the air again for the 335-mile flight to Recife. But, as copilot Ruiz de Alda recalled: “On this short stage we suffered a grave accident. The propeller of the rear engine broke. We had to stop it but the front engine was not powerful and we had to come down to sea level. We had to throw everything overboard, including our luggage. Franco managed to stay airborne but at times we touched the waves; it was only as the fuel load lessened that we could gain any height.”

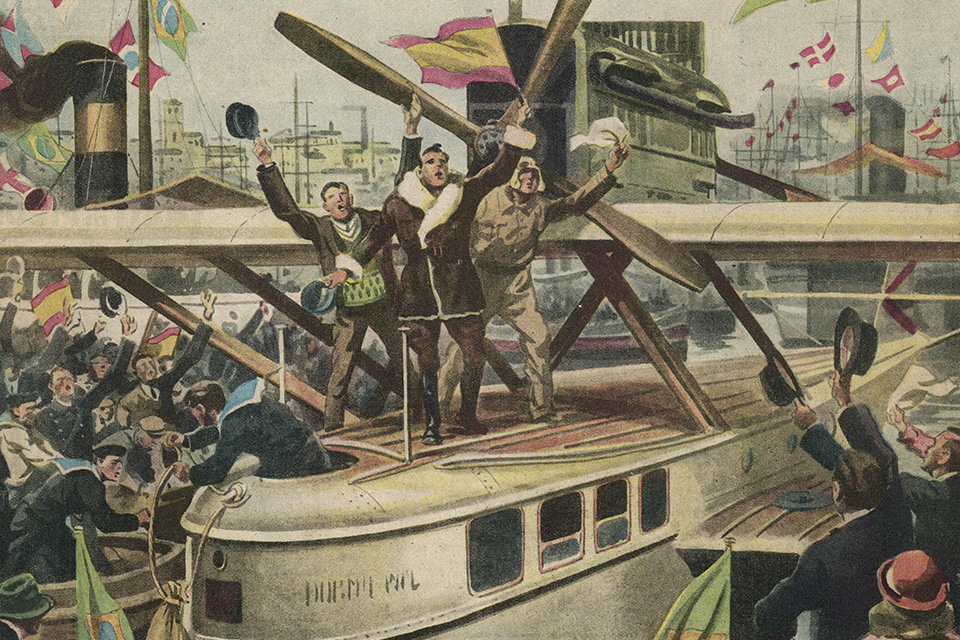

“Our arrival in Pernambuco [Recife] made up for the bad experience,” he continued. “We flew at a height lower than the coconut trees of the coast….After this chase along the coast, we arrived at Pernambuco, where an indescribable welcome awaited us.” Another contemporary account recorded, “Three miles of quays were lined with cheering crowds, and while, as guests of honor, they were being escorted aboard a Brazilian destroyer, all the ships in the harbor hooted a jazz serenade on their sirens.”

Plus Ultra’s triumphal progress continued southward along the South American coastline. Departing from Recife on February 4, the Wal crew completed the 1,302 miles to Rio de Janeiro in 12 hours, 16 minutes, with Franco remaining at the controls throughout. Ruiz de Alda recounted some of the dangers posed by the wildly overenthusiastic welcome that greeted their arrival: “The unparalleled Bay was full of every kind of boat….The landing was very difficult because of all the obstacles that endangered our plane. One of the many boats that wanted to sail beside us managed to break our rudder.”

Plus Ultra’s replacement two-bladed propeller and unsuitable fuel combined to require two long takeoff attempts before it finally departed from Rio on February 9, covering the 1,277 miles to Montevideo in 12 hours and 5 minutes. The next day they made the short 136-mile hop to Buenos Aires, where yet another tumultuous welcome awaited them at their journey’s end. They had flown more than 6,300 miles in just under 51 hours’ flying time—an outstanding achievement by the standards of the day, even if it did not receive the international acclaim generally bestowed on North Atlantic flight attempts. To some the South Atlantic—with its shorter distances, absence of fog and ice, and east-west prevailing winds—was seen as the “easy option,” although it was often anything but.

Franco had originally intended to fly Plus Ultra back to Spain via Chile, Mexico, Cuba and the Azores. The Spanish government decided, however, that as a mark of Hispanic solidarity, the Wal should be presented to the Argentine nation. (Today it is on display at a museum in Lujan, Buenos Aires.) Franco and his crew returned home aboard the Argentine navy cruiser Buenos Aires to yet another fervent welcome, including the award of decorations personally bestowed by Spanish King Alfonso XIII. Ramon Franco’s star was definitely in the ascendant.

Franco was back in the public eye again on August 1, 1928, when he took off from Cadiz in the Spanish-assembled Dornier R4 Nas Super Wal Numancia, powered, at his insistence, by four British 500-hp Napier Lion engines. With him were copilot Eduardo Gonzalo, navigator Ruiz d’Alda and mechanic Pablo Rada. They were bound for the Azores in what was intended to be the first leg of a highly ambitious 20-stage 25,000-mile westward flight around the world. Unfortunately, mechanical problems soon compelled Franco to make a forced landing off Faro, on the Gulf of Cadiz, and then to head to Huelva for urgent repairs.

The experience apparently prejudiced Franco against Wals assembled by the Cadiz-based Construcciones Aeronauticas SA. However, when the Spanish government approved a second round-the-world attempt, using a standard Hispano-Suiza powered, Spanish-assembled Wal, Franco reluctantly agreed. He and his crew took off in this Wal, also named Numancia, on June 21, 1929, bound for the Azores, Halifax and New York. But once again they never made it.

Franco later recounted in the magazine Flight: “We left Los Alcazares at 1700 hours, June 21, passing Cape St. Vincent at 2100 hours. From the Cape we were forced to gain height due to excessive air disturbances. From Cape St. Vincent to the Azores was an uninterrupted layer of cloud above which we had to fly. Later another cloud layer formed above us. The intended time of our arrival at the Azores was 0900 GMT on June 22. But a strong northeast wind, which we were unable to foresee or check in flight, caused us to pass over the Azores in the dark. At dawn we took our longitude by the sun, which showed we were to the southwest of the Azores. We therefore flew through the clouds and alighted to economize fuel and examine the situation more closely. We checked our position and took off, shaping a course for Fayal but, owing to strong headwinds, ran out of petrol about 40 miles from that point. Strong northeasterly winds drifted us to the south, and, on the following day, June 23, we were about two miles from Fayal. The wind shifted to the southwest, reaching gale force, and drifted us to the island of Santa Maria. From June 24 to 27 winds of varying force and direction drifted us about. On the morning of the 27th the situation was extremely dangerous on account of the wind and sea conditions.”

Meanwhile, as Spain waited nervously for news of Franco and his crew, ships and aircraft from several nations mounted an extensive search until on June 29, when hope of their survival had almost been abandoned, the British aircraft carrier HMS Eagle found Numancia. The exhausted crewmen were taken aboard and their battered flying boat winched up onto the deck. They arrived in Gibraltar to a heroes’ welcome, exceeded only by the outburst of patriotic fervor that followed later in Madrid.

Not long after, Franco’s popularity took a sudden nosedive. The cause was a rumor that, not wishing to use a Spanish-assembled Wal, he had somehow arranged for a German-built machine to be substituted and its registration numbers changed. There was even a suggestion that he had accepted a bribe from Dornier. The crucial flaw in the rumor was that no Wals had actually been built in Germany at that time and would not be until 1931. In another, marginally more credible version of the story, he was supposed to have substituted an Italian-built Wal for the Spanish-assembled flying boat. Inevitably some mud stuck, and Franco’s reputation as a heroic patriot was duly tarnished. Furthermore, he was disciplined for alleged gross negligence in embarking on a transatlantic flight when the weather forecast was unfavorable.

Proud, impulsive, moody and ambitious, Franco subsequently made several ill-judged forays into the maelstrom of factional politics before committing himself to his brother Francisco’s Nationalist side by the start of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. Promoted to lieutenant colonel, he took command of the Majorca air base. The appointment did not please his fellow Nationalist aviators, who felt they had been unjustly overlooked for promotion.

On October 28, 1938, Franco set out on a mission from Palma with another aircraft (which turned back) to bomb Republican-held Valencia. His Cant Z 506 Airone trimotor floatplane crashed in a storm off Pollenca, on the Majorcan coast. Franco and the three other crewmen were killed.

With such a controversial figure as Franco, rumors of conspiracies and sabotage were perhaps unavoidable, though never proven. In the fog of war, his death went largely unnoticed and to a certain extent unlamented, most notably by his elder brother Francisco, the ruthless soldier who would go on to be Spain’s dictator.

Ramon Franco deserved better. For all his foibles, he was a highly accomplished and courageous long-distance pioneer who had earned a distinguished place in aviation history.

RAF veteran and frequent contributor Derek O’Connor recommends for further reading: Atlantic Air Conquest, by F.H. and E. Ellis; Through Atlantic Clouds, by Clifford Collinson and F. McDermott; and The 91 Before Lindbergh, by Peter Allen.

This feature originally appeared in the January 2018 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today!