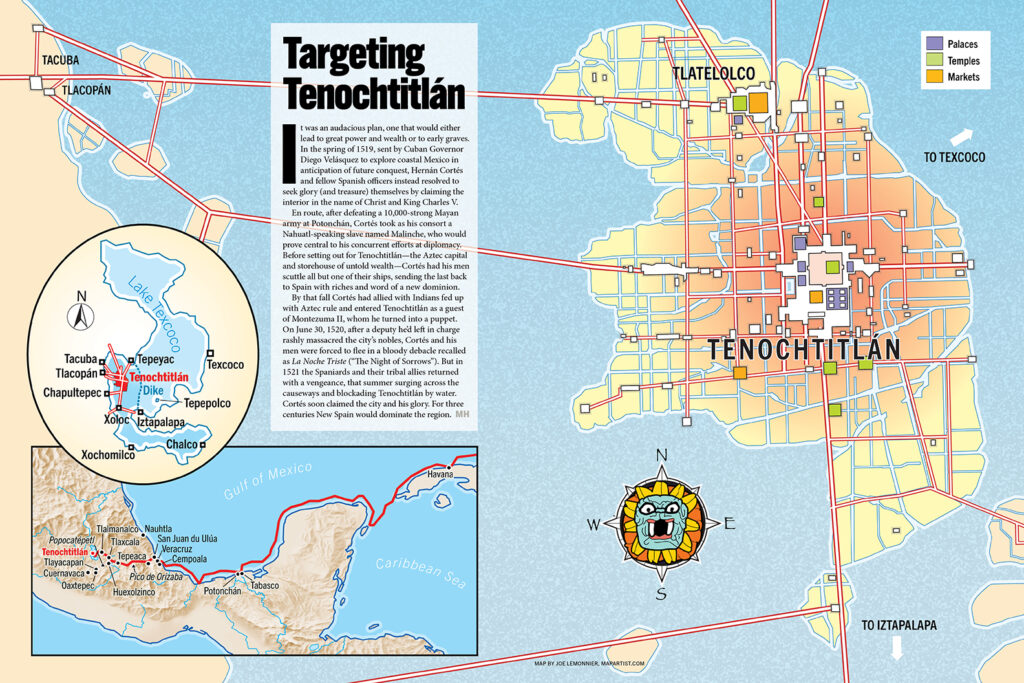

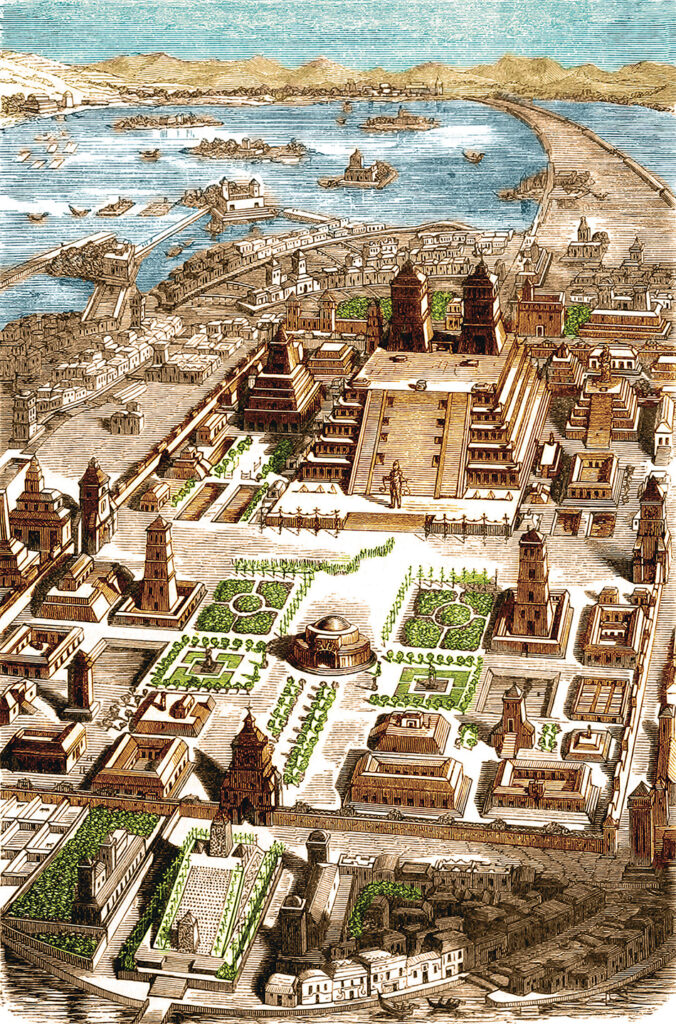

For the sick, half-starved inhabitants of Tenochtitlán, island capital of the beleaguered Aztec empire, the new year of 1521 offered only severe hardship and continued bloodshed. Over the past eight months the city’s quarter million residents had suffered through the deaths of two emperors, Montezuma II and his brother Cuitláhuac; the loss of the entire upper echelon of the empire’s military and political elites to a cowardly Spanish massacre; and a 70-day scourge of smallpox that killed tens of thousands and claimed Cuitláhuac’s life, on December 4. His nephew Cuauhtémoc, as 11th Aztec emperor (known as the huey tlahtoani, or “great speaker”) and commander in chief, was left to defend the city against a coalition army of aggrieved Indians and determined Spanish conquistadors led by Hernán Cortés.

After reaching Hispaniola in 1506, Cortés prospered in the West Indies. Several years of civil service in Cuba, in the wake of its 1511 conquest by Diego Velásquez de Cuéllar, had earned him an encomienda, a large estate complete with thousands of indigenous laborers compelled to work in mining and agriculture. Appointed governor of Cuba, Velásquez was planning to finance his own campaign of conquest on the mainland of Mexico when he sent his secretary, Cortés, on a limited mission to explore the coast in 1519. Cortés and several veteran officers, however, opted to pursue a far more ambitious, albeit unsanctioned, undertaking—the expansion of the Spanish empire into Mexico and beyond, in the name of Christianity, while acquiring vast wealth, land and renown for themselves.

Disembarking at Tabasco on March 12, Cortés and 630 Spaniards moved inland and encountered the Mayans of Potonchán, who answered his request for talks with torrents of arrows, spears and stones that had little effect on Spanish armor. Facing overwhelming numbers, Spanish soldiers armed with harquebuses, crossbows, pikes and steel swords and accompanied by heavy artillery, mounted lancers and war dogs routed some 10,000 attackers, after which the defeated Mayans provided Cortés with 20 women slaves, among them the Nahuatl-speaking Malinche, who became Cortés’ invaluable interpreter, consort and mother of his first son.

Sailing north along the coast, the Spaniards came ashore near San Juan de Ulúa on April 21 and, in a veiled attempt to legitimize their expedition, founded a new colony at Veracruz “in His Majesty’s name.” Cortés then marched north to Cempoala, home to the Totonacs, where for the first time the conquistador leader moved to exploit a tributary population’s bitterness toward Tenochtitlán. Resentful subjects of the empire since 1480, the Totonacs forged an alliance with Cortés, who directed them to cease paying tribute, which could include military service, gold, foodstuffs, trade goods or captives (some of the latter were enslaved, while others were ritually sacrificed and eaten). After scuttling all but one of his ships (which sailed for Spain carrying slaves and treasure to be presented to Charles V, king of Spain and Holy Roman emperor), Cortés pushed inland on August 16 accompanied by 800 Totonac warriors.

Cortés and his host had barely entered Tlaxcalan territory when they were ambushed by a disciplined force of warriors led by their commander in chief, Xicotencatl the Younger. Home to upward of 150,000 people, Tlaxcala was a confederation of four hill provinces united against their Aztec archenemies in Tenochtitlán, who for decades had oppressed them with embargoes on salt, gold and cotton and demands for captives as tribute. After several clashes with the Spaniards, Xicotencatl the Elder and the city’s other lords halted hostilities and invited Cortés into their capital on September 23. Awed by the expedition’s horses and gunpowder weapons, Xicotencatl the Elder, who like Cortés was looking for powerful allies, agreed to an alliance (see “The Warriors Who Nearly Destroyed Cortés—Before Joining Him,” by Justin D. Lyons, online at HistoryNet.com).

On November 8, with 2,000 Tlaxcalan warriors, porters, guides and cooks added to the Spanish ranks (the Totonacs had returned home), Cortés boldly marched into Tenochtitlán, where Montezuma extended the Spaniards a diplomatic if wary welcome. A week later events on the Gulf of Mexico gave Cortés a pretext to act. After Aztec tax collectors in the town of Nauhtla demanded local Totonacs pay their customary tribute and were refused, fighting broke out, and the Aztecs slew several Spaniards and Totonacs. Accusing Montezuma of collusion in the bloodshed, Cortés brazenly arrested the stunned emperor and ordered him to reside in the Spanish quarters under guard. After getting assurances of his safety from Malinche, the shaken emperor acquiesced, allowing Cortés to usurp his host and take effective control of the city for the next six months.

The Spaniards had amassed eight tons of looted gold and silver when, with Cortés absent from the city, his deputy, Pedro de Alvarado, led an unprovoked attack against celebrants at the Festival of Toxcatl, hacking to death hundreds of senior military and political leaders and their families. The atrocity touched off a violent citywide revolt that trapped the Spanish/Tlaxcalan forces inside their quarters under a rain of spears, stones and arrows from surrounding rooftops. Cortés returned on June 24, 1520, to find Alvarado’s actions had put the entire expedition in peril, leaving the Spaniards no choice but to flee the city with their sick, wounded, artillery and treasure in tow.

At midnight on the rainy night of June 30, Cortés led his assembled host—1,300 Spaniards and 2,000 allies—from Tenochtitlán onto the Tacuba causeway, heading west out of the city. The van had marched but a quarter mile along the causeway when the escape attempt was discovered. Hundreds of canoes soon filled surrounding Lake Texcoco, bringing the long column strung out along the span under withering missile fire while warriors streamed out of the city on foot to attack the column from the rear. After six terrifying hours Cortés and other survivors stumbled ashore, having lost as many as 800 Spaniards and more than 1,000 allies killed, captured or drowned, along with most of the horses and all the gunpowder, cannons and treasure.

Incredibly, the crushing defeat—recorded by the Spanish as La Noche Triste (“The Night of Sorrows”)—wasn’t enough to convince the redoubtable Cortés to abandon the campaign. Most of his veteran captains and mounted lancers, his interpreter, Malinche, and shipwright Martin López, the one man who could construct new warships for a return assault on Tenochtitlán, had survived the carnage. Gathering his wounded, hungry forces—about 500 Spaniards and 800 Tlaxcalans—Cortés led the small band 150 miles through hostile territory armed only with swords, crossbows, lances and pikes, reaching Tlaxcalan territory on July 9.

As Cortés himself recovered from a fractured skull, his fortunes turned for the better. Xicotencatl the Elder refused Cuauhtémoc’s offer of tribute relief and instead agreed to a new “perpetual alliance” with Cortés, while supply ships from Spain and Cuba—the Crown having dismissed mutiny charges against the expedition leader—arrived at Veracruz laden with men, horses, weapons, gunpowder and provisions. In August, backed by 2,000 loyal Tlaxcalans, Cortés captured the mountaintop redoubt of Tepeaca, a critical Aztecan ally, then used it as a base to subdue the surrounding villages. Some towns submitted voluntarily. Others were sacked, their male populations executed, their women and children branded and sold into slavery. By autumn 1520 Cortés was the strongest entity in the vast flatlands between the Popocatépetl and Pico de Orizaba volcanoes and had effectively cut off Tenochtitlán from the Gulf of Mexico. Before leaving Tepeaca, Cortés tasked López with constructing a fleet of 13 brigantines at Tlaxcala using native labor and salvaged hardware, after which the finished ships would be dismantled, carried over the mountains, reassembled and launched on Lake Texcoco.

Intent on first subduing the cities ringing the lake, Cortés gathered 550 Spanish infantry, 40 horsemen and 10,000 handpicked Tlaxcalans and in late December 1520 marched for Texcoco, still nominally an Aztec ally. As the Spaniards approached, they were met by emissaries from rebel Texcocan warlord Ixtlilxochitl II, who joined the advance with his own warriors and thousands of canoes. Arriving at Texcoco, Cortés and his growing force found it virtually abandoned, its tlahtoani and citizens having fled across the lake to Tenochtitlán. After sacking the city, Cortés pronounced Ixtlilxochitl Texcoco’s new tlahtoani, at a stroke bloodlessly adding another powerful ally to his ranks. The consequent Aztec loss of Texcoco, with its bountiful harvests and strategic location on the lake’s eastern shore, was a crippling blow to Tenochtitlán. As occurred at Tepeaca, the Spaniards’ success compelled the lords of neighboring cities to visit Cortés’ camp and offer their allegiance.

In early January 1521, on learning that Chalca cities south of the lake were restive, Cortés led 200 Spaniards and 4,000 allies to sack Iztapalapa, while his lieutenant Gonzalo de Sandoval evicted Aztec garrisons from Chalco and Tlamanalco, loosening Tenochtitlán’s grip on the region. At the urging of his two powerful allies, Cortés further isolated Tenochtitlán by subduing Tlacopán, the last city-state of the Aztec Triple Alliance. (In 1427–28 Itzcoatl, the fourth Aztec emperor, had led Tenochtitlán, Texcoco and Tlacopán to decisive victory in their rebellion against Azcapotzalco, after which the victors had formed the Triple Alliance to share in future wars of conquest. By 1519, after nearly a century of aggressive expansion, the alliance was dominated by Tenochtitlán, its borders stretching from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico south almost to Guatemala, which extracted tribute from nearly 500 cities and towns in the Valley of Mexico and beyond, backed by the constant threat of military force.)

After Sandoval repulsed a major Aztec attempt to retake Chalco on March 25, Cortés moved to subdue the region south of Lake Texcoco. With 300 infantry, 30 horsemen, 35 crossbowmen and harquebusiers, and 20,000 Tlaxcalan/Texcocan allies he seized Tlayacapan and Oaxtepec, then sacked Cuernavaca (April 13) and Xochimilco (April 16), further isolating Tenochtitlán from sources of supply and reinforcement. After five months of campaigning, Cortés had subdued or accepted the submission of almost all the cities on the lakeshore and in the Valley of Mexico, had received supplies and reinforcements, and was ready to march for Tenochtitlán. Intent on obtaining Cuauhtémoc’s unconditional surrender, Cortés was prepared to destroy the city block by block and let his allies sack it if necessary.

Cortés received good news when he returned to Texcoco: The brigantines were ready. Averaging 50 feet in length (Cortés’ flagship, La Capitana, was 65 feet long), each was armed with two guns and carried a captain, 12 oarsmen, six harquebusiers and six crossbowmen. The Spaniards launched them on Lake Texcoco on April 28. Cortés organized his remaining forces into three infantry divisions under Alvarado, Sandoval and Cristóbal de Olid, their objective to seize control of the main causeways into the city. Each division was allotted some 150 foot soldiers, 30 horsemen, 15 crossbowmen and harquebusiers and a detachment of native allies numbering around 8,000. Thousands more Texcocans and Tlaxcalans would follow Cortés’ brigantines in a flotilla of canoes commanded by Ixtlilxochitl, and the combined fleets would support the land assaults, blockade the city and destroy enemy vessels.

Alvarado and Olid departed Texcoco first, arriving at Tlacopán on May 25. The next morning they rode to Chapultepec, on the lake’s western edge, broke through the Aztec defenses and destroyed the aqueduct there, permanently severing Tenochtitlán’s source of fresh water. Over the next 75 days the city’s citizens would have to rely on grossly inadequate supplies of brackish water extracted from wells and springs.

Versus Armor

Tipped with razor-sharp obsidian points like that above, Aztec spears and arrows had little effect on Spanish armor. Cortés’ men carried harquebuses, crossbows and swords and were supported by artillery, mounted lancers and war dogs. That said, they were few in number.

With his ground units deployed, Cortés committed the brigantines to the fight on June 1. Observing smoke signals rising from the tiny island city of Tepepolco, warning Cuauhtémoc of the Spanish advance, Cortés landed with 150 men and wiped out that city’s entire garrison. Setting off once more, Cortés’ warships smashed through a flotilla of 600 Aztec canoes sent to intercept them, the brigantines’ high decks thwarting boarders and providing cover for harquebusiers and crossbowmen to fire and reload. “Nothing in the world gave me such joy as to see all 13 sails with a fair wind scatter the enemy,” recalled Sandoval, who observed the engagement from Iztapalapa. Following in Cortés’ wake, the Texcocan canoes destroyed any Aztec canoes that remained afloat. Exploiting his success, Cortés sailed on and seized the key fortress of Xoloc, on the southern causeway from Iztapalapa to Tenochtitlán. Olid then joined Cortés and Sandoval at Xoloc, further improving their strategic situation.

For his part, Cuauhtémoc was directing operations from a canoe in the lake, sending waves of Aztec warriors armed with spears and steel arrows (fashioned from Spanish swords retrieved from the lake) against Cortés, Sandoval and Olid at Xoloc and Alvarado at Tlacopán. Meanwhile, Aztec laborers erected fortifications, opened breaches along each causeway to close the roads to Spanish horsemen and planted sharp stakes in the lake’s shallow waters to pinion the brigantines. The emperor’s aggressive tactics and vast manpower reserves made Cortés’ advance slow and costly.

In mid-June, however, Sandoval sailed north of the city and blocked the last open causeway, leading from Tlatelolco (a subject of Tenochtitlán since 1473) to Tepeyac. Tenochtitlán was surrounded, cut off from all supplies, food, water and hope.

On June 10 and again on the 15th, as Sandoval and Alvarado pressed their respective attacks along the northern and western causeways, Cortés led Olid’s division on major assaults into the city from the south, encountering fierce Aztec resistance before withdrawing. A pattern soon emerged: Escorted by the brigantines, the Spaniards and their allies advanced each morning as far as possible into the city and fought all day before falling back to their fortified camps in the evening, destroying buildings along the way. Aztec laborers appeared each night to again dig ditches in the causeways, forcing the attackers to fill them in again the following day. By late June the besiegers were penetrating into the city at will, though Cortés was well aware of the danger of being ambushed and trapped inside the city. The tenacity of the defenders—facing land and water assaults daily on three fronts—was astounding.

As Aztec fortunes waned, more of its former allies joined Cortés, including contingents from Huexotzinco and Xochimilco. Morale inside the city plummeted when no festivals were held or crops were planted in June. The lack of able-bodied commoners available to sow crops brought on starvation and finally famine.

An increasingly desperate Cuauhtémoc abruptly changed tactics and moved his remaining warriors to the neighboring island suburb of Tlatelolco, whose narrow streets and fortified marketplace precinct were better suited to urban warfare. Believing the Aztecs were fleeing, Cortés led a three-pronged attack against Tlatelolco on June 30 that he hoped would end all resistance. After initial gains, the attackers fell into an ambush and, with their withdrawal route blocked, suffered a stinging defeat in which some 20 conquistadors and 2,000 allies were slain. Worse yet, dozens of Spaniards and allied warriors were captured and ritually sacrificed. After watching their comrades slaughtered, most of the remaining allied warriors melted away, leaving Cortés to fear another Noche Triste.

In the final crisis of the campaign Cortés dispatched Spanish/allied contingents to aid two of his new allies against Aztec threats. Two quick victories restored the strategic advantage to Cortés, and the indigenous army that had abandoned him returned, leaving Cuauhtémoc unable to exploit his victory. After his allies returned, daily incursions into both Tlatelolco and Tenochtitlán proper resumed, and though several brigantines had been lost, the allied fleets still controlled Lake Texcoco, and the blockade of the city remained in place.

Tactical Takeaways

Enemy of my enemy. Cortés shrewdly allied with the Aztecs’ bitter enemies and disaffected tributary states. Without them the Spanish could never have prevailed. Carrot and the stick. Cortés’ combination of diplomacy and violence bore fruit. By contrast, a deputy’s decision to massacre Aztec leaders nearly cost the Spaniards their lives and an empire. But can you keep it? Cortés conquest was undoubtedly a signal achievement. But after a few centuries of Spanish rule, the subject states of New Spain revolted.

By mid-July conditions within Tenochtitlán were appalling. Sick, starving refugees filled the streets, tribute was being interdicted and most of the chinampas (floating gardens) that provided the bulk of the city’s food had been destroyed. On their daily sorties the attackers had taken to dismantling entire city blocks, tearing down temples and houses to give Spanish horsemen room to operate and crossbowmen and harquebusiers fields of fire.

By month’s end Aztec attacks on the Spanish camps had ceased and exhausted laborers were no longer able to sever the causeways. Aztec prisoners reported that the city’s inhabitants were starving, and Cuauhtémoc had resorted to conscripting women to fill his ranks. Early on July 27 Cortés was at Xoloc when he saw smoke rising from Tlatelolco’s main temple, a sign Alvarado had overrun the last Aztec line of defenses there and captured the great marketplace, ending all organized resistance. Cuauhtémoc refused to surrender, though, prolonging his people’s suffering, and it wasn’t until August 13 that he was apprehended while fleeing across the lake with his family. With Tenochtitlán reduced to smoking ruins, the Aztec empire had ceased to exist. Brought before Cortés, Cuauhtémoc was tortured in a futile attempt to discover the whereabouts of any stashed gold, then was forced to play the role of puppet ruler before being executed on false charges in 1525.

After reaching Tenochtitlán in September 1520, smallpox claimed almost 100,000 citizens’ lives. In the ensuing decades epidemics of measles, whooping cough, mumps, influenza and typhus helped reduce the population of central Mexico from the more than 8 million when Cortés landed to little more than 1 million a half century later. The steady depopulation of the Taino peoples of Hispaniola due to disease and overwork—their numbers fell from 200,000 in 1492 to 90,000 in 1515—forced its Spanish governor in February 1510 to authorize the transport of 250 African slaves from Spain to work its gold mines. In August 1517 Charles V authorized the governor to import 4,000 more. Meanwhile, in the two centuries after 1492 some 750,000 people left Spain to escape poverty or seek adventure in the New World.

With almost no oversight from the mother country Cortés and his men acted as a law unto themselves, destroying and founding new cities and turning entire conquered populations into indentured servants, their legacy one of conquest, colonization, depopulation and exploitation. Indeed, at their peak fully a quarter of all imperial Spanish revenues would be bullion from Mexico and Peru; 180 tons of gold and 16,000 tons of silver reached Spanish shores from the New World between 1500 and 1650, fueling Spain’s rise as a superpower and funding Charles V’s wars in Italy and against the Protestant Reformation.

The conquest of central and southern Mexico was followed by the violent subjugation of the rest of Mesoamerica—comprising the modern countries of Nicaragua, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala and Belize—and parts of South America. Gradually, Franciscan friars arrived to spread Christianity, bureaucrats replaced the conquistadors, and in 1535 Antonio de Mendoza became 1st Viceroy of New Spain. “The conquistadors, who put an end to human sacrifice and torture on the Great Pyramid in Mexico City,” wrote historian Victor Davis Hanson, “sailed from a society reeling from the Grand Inquisition and the ferocious Reconquista and left a diseased and nearly ruined New World in their wake.”

John Walker is a California-based freelance writer and a Vietnam War veteran. For further reading he recommends Tenochtitlán 1519–21: Clash of Civilizations, by Si Sheppard; Conquistadores: A New History of Spanish Discovery and Conquest, by Fernando Cervantes; and Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise to Western Power, by Victor Davis Hanson.

This story appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of Military History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.