Sarojini Naidu was born in Hyderabad, India, in 1879. Her father, a prominent educator and political activist, and her mother, a poet, would both be important influences in her life. As a child Naidu learned to speak five languages, including English, and she attracted national attention when she entered the University of Madras at age 12. Around that time she began writing poems and plays, and at age 16 she went to England to study at King’s College in London and, later, at Girton College in Cambridge. She made a name for herself in the London literary scene as a protégée of Edmund Gosse and Arthur Symons, two influential poets and critics. Her first volume of poetry, The Golden Threshold, was published in 1905, and the second, The Bird of Time, in 1912. In 1914 she was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

Years earlier, incensed by Britain’s religion-based partitioning of Bengal in 1905, Naidu had joined the Indian National Congress, and with each passing year she became more deeply involved in the Indian independence movement and in advocating for women’s rights in her homeland. (In 1925 she became the first Indian woman to serve as president of the Indian National Congress.) Naidu was drawn to Mahatma Gandhi’s Noncooperation Movement—the campaign of civil disobedience he waged against British rule in India—and in time became one of his closest associates. (She playfully called Gandhi “Mickey Mouse,” while he referred to her “the nightingale of India.”) In 1930 she accompanied Gandhi on the Salt March—an epic nonviolent protest against Britain’s control of salt production and distribution in India—and the following year accompanied him to London for the second Round Table Conference, a summit on India’s future. She was twice imprisoned for her anti-British activism in the early 1930s, and in 1942 she and Gandhi were jailed for 11 months.

After India achieved independence in 1947, Naidu became the first female governor of a state, the Upper Provinces (present-day Uttar Pradesh), a post she held until her death from a heart attack in 1949. The anniversary of her death is commemorated as Women’s Day in India.

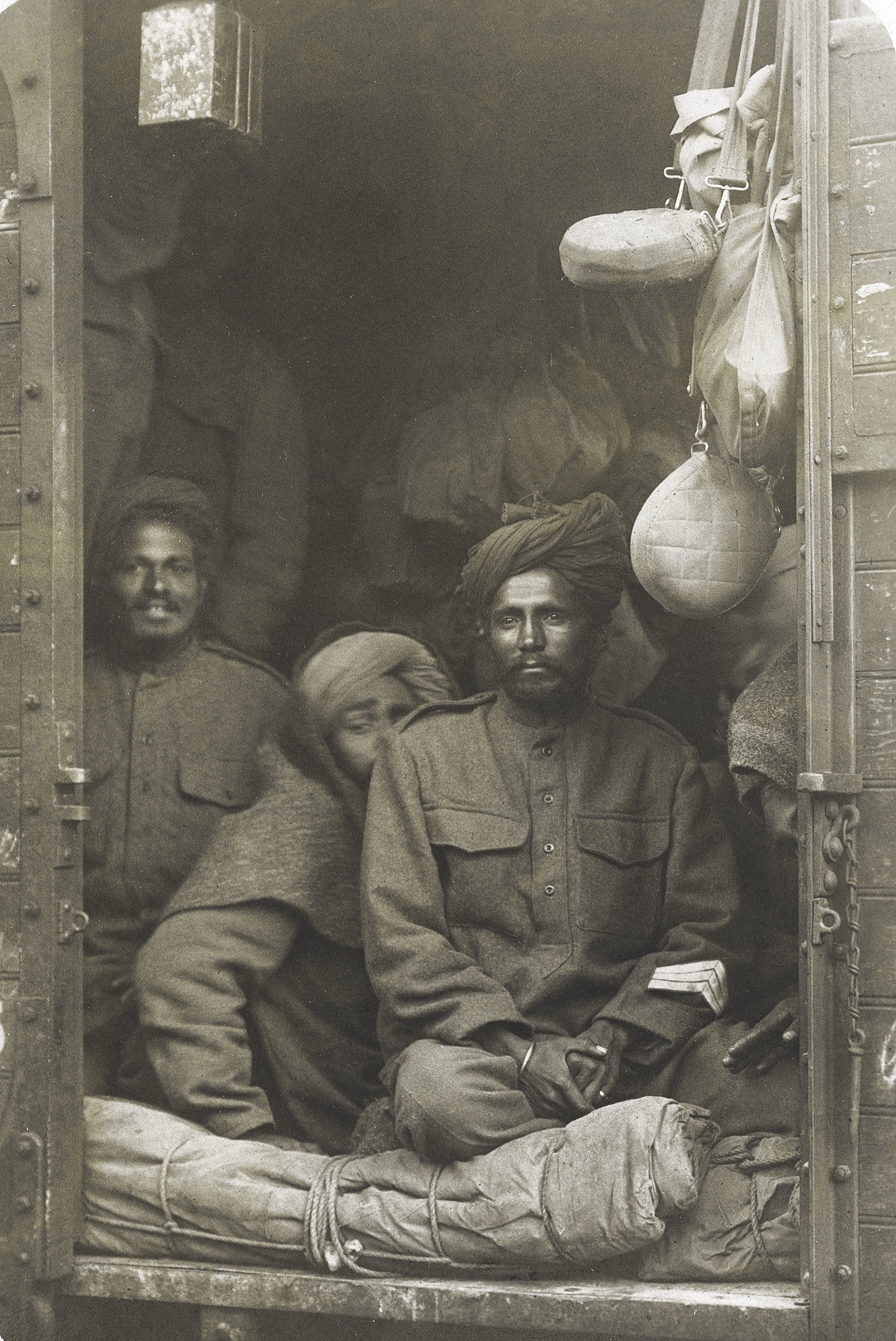

In the poem that follows, which was originally published in 1916 in the Westminster Gazette, an influential London newspaper, Naidu pays tribute to Indian soldiers who lost their lives fighting for Britain in World War I. In all, some 1.3 million Indian soldiers fought on the Western Front as well as in Mesopotamia and Gallipoli; more than 75,000 of them died.

The Gift of India

Is there aught you need that my hands withhold,

Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold?

Lo! I have flung to the East and West

Priceless treasures torn from my breast,

And yielded the sons of my stricken womb

To the drum-beats of duty, the sabres of doom.

Gathered like pearls in their alien graves

Silent they sleep by the Persian waves,

Scattered like shells on Egyptian sands,

They lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands,

They are strewn like blossoms mown down by chance

On the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France.

Can ye measure the grief of the tears I weep

Or compass the woe of the watch I keep?

Or the pride that thrills thro’ my heart’s despair

And the hope that comforts the anguish of prayer?

And the far sad glorious vision I see

Of the torn red banners of Victory?

When the terror and tumult of hate shall cease

And life be refashioned on anvils of peace,

And your love shall offer memorial thanks

To the comrades who fought in your dauntless ranks,

And you honour the deeds of the deathless ones,

Remember the blood of my martyred sons!

[hr]

This article appears in the Spring 2021 issue (Vol. 33, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Poetry | The Nightingale’s Lament

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!