People in England and France kept telling me about the statues. They were–to use a Michelin guidebook phrase that skips so easily off European tongues–”worth a visit.” I was preparing for a trip along the old Western Front and I was eager not to miss anything important.

The statues had been done by the German artist Kathe Kollvitz as a memorial to her son; they presided over a German military cemetery near a village a few miles in from the Belgian coast Vladslo. I had to ask someone to spell it.

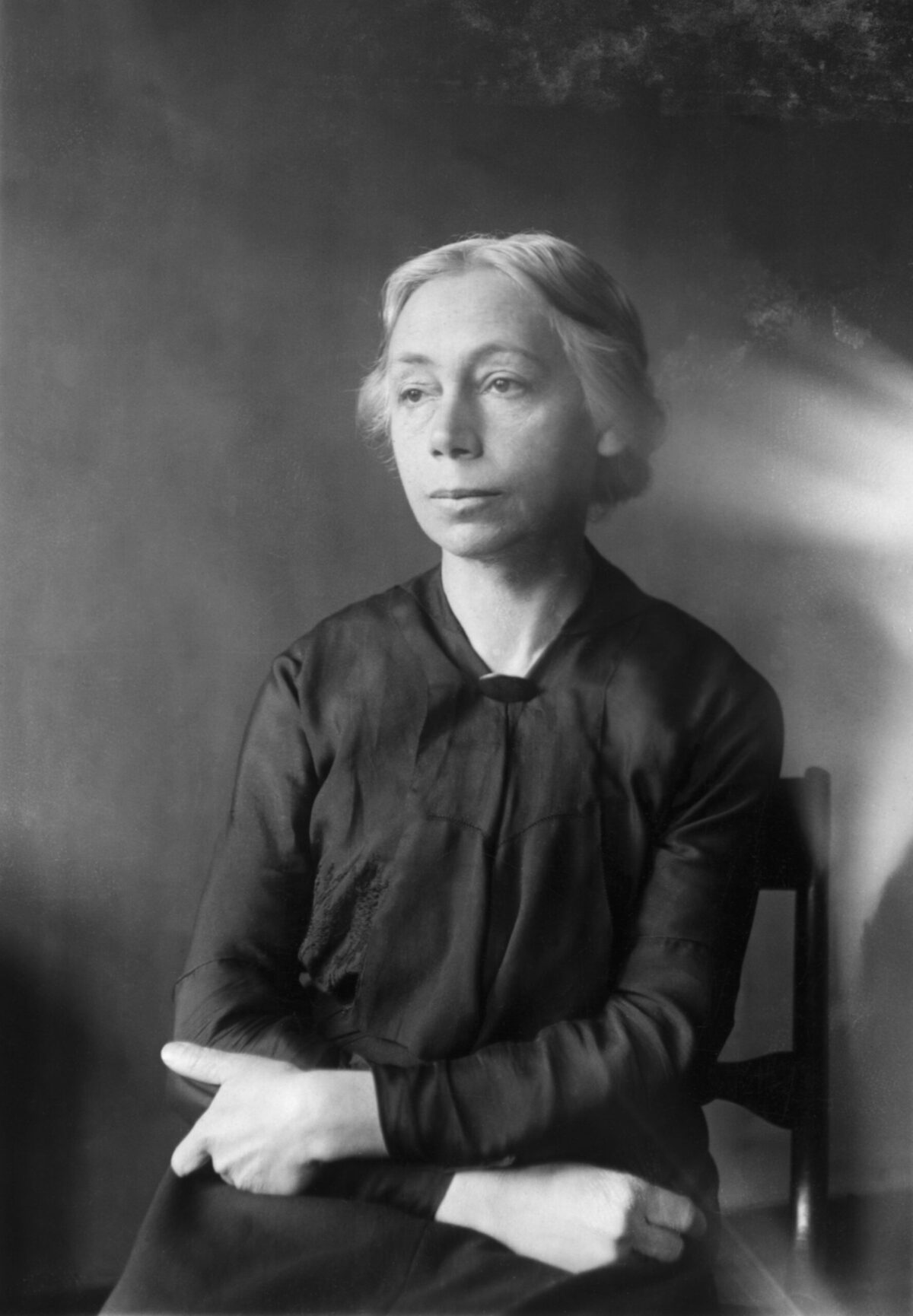

These days Kathe Kollwitz seems consigned to the same obscurity. She is not so much dismissed as ignored. A half century ago, however, many considered her Germany’s leading woman artist. She was a folk heroine of the Left, her work suppressed by the Nazis. Later, feminists made canonizing motions, which never took. People like their saints to be influential, but Kollwitz was out of the mainstream of modern art, primarily a graphic artist who worked almost exclusively in black and white at a time when color had ignited a revolution in German painting. Kollwitz produced no paintings to speak of, no works acclaimed as major. I might amend the last when it comes to statues–but that is getting ahead of my story.

For me, that story began as I floundered around the back roads of rural Belgium. I drove in circles searching for the cemetery with the Kollwitz statues. This is some of the most densely populated agricultural land in Europe–in places there are nearly 900 people per square mile–though you would never know it from casual observation. The people are well hidden. The farmers here tend to live not in isolated houses but in villages, and those villages crop up around every other bend. Take any of the narrow, tree–arched lanes that lead off from the main traveled roads and you will find not the mingy, land-consuming roadside development of our rural sticks but yet another tidy, prosperous, dark brick settlement. Strip development in the American manner hardly exists.

In these Flanders villages; it’s true, you’ll find the tentative beginnings of an outward spread, the new brick split-level villas edging into the farmland; the Flemish are fast becoming a population of managers and service workers, with suburban nesting habits similar to ours. But the fields still crowd in on the houses, rather than the other way round, and the rural maze remains as mazy as ever. Is it any wonder that in 1914 whole armies blundered down these same country lanes as blindly as I was doing now?

I found the Vladslo Military Cemetery, eventually, recognizing it by the brownstone gatehouse all but hidden in a long hedge. I had to pass through a gloomy chamber, its walls laden with a claustrophobic throng of names–”these intolerably nameless names,” Siegfried Sassoon called them, forever trapped in the elevator of history. Beyond, in the late-afternoon shadows, trees crowded in on a darkening lawn, their leaves an unbearably lush summer green. I felt a little as though I had come on a forest clearing in a tale by the brothers Grimm, a glade where a dwarf might once have guarded the waters of life. Military cemeteries, with their deliberately unreal celebration of the cult of the fallen, have that fairy-tale quality, edgy and sinister.

But there was also something faintly industrial about this place. The lines of flat, square, basalt gravestones barely rising above the grass looked like skylights on a factory roof. Each stone-and there were hundreds of them–listed the names and death dates of as many as 20 men per grave. A total of 25,664 men are buried at Vladslo, including Kathe Kollwitz’s son Peter.

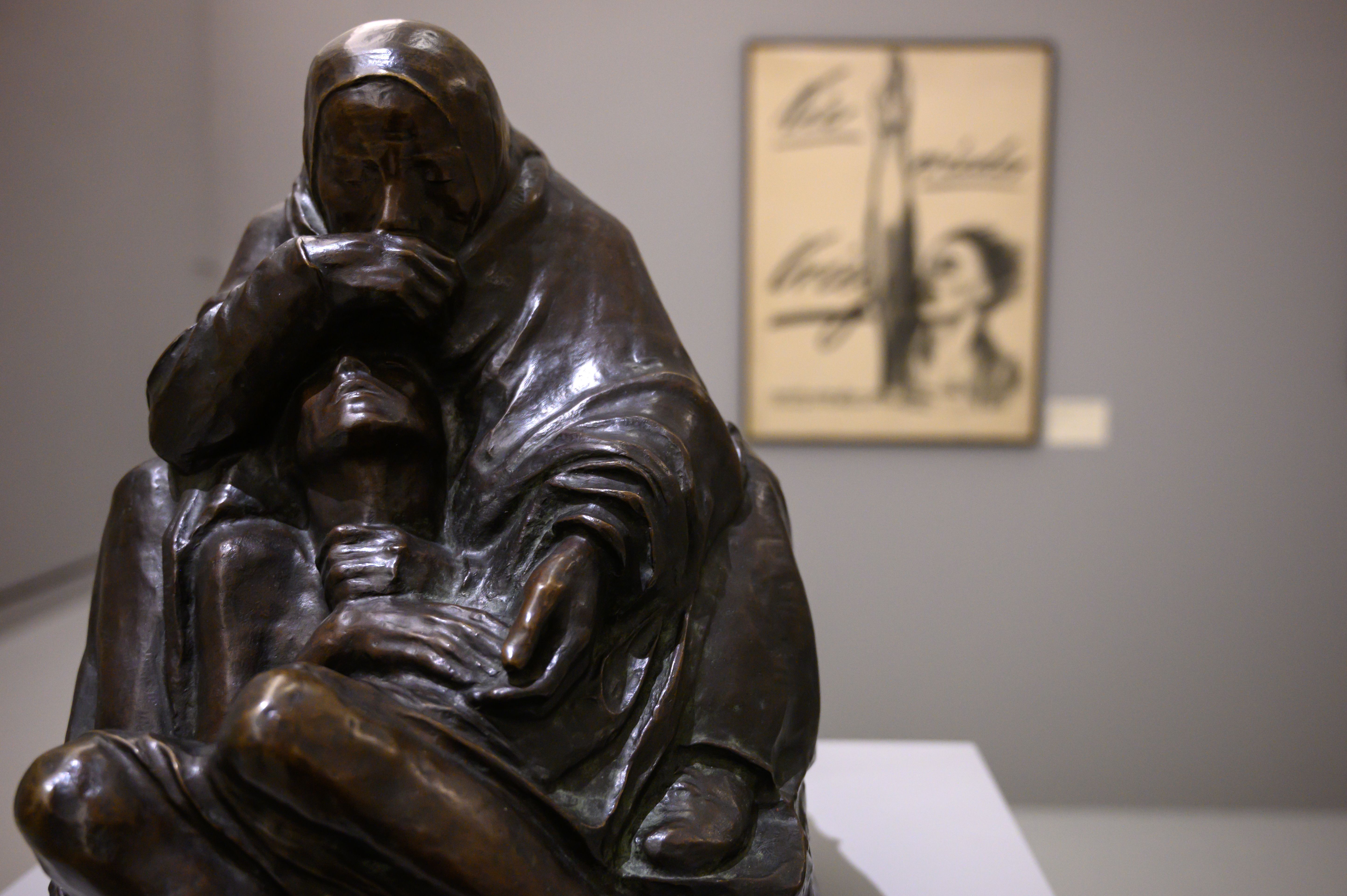

I spotted the statues at the far end of the cemetery, backed up against a dark beech hedge–”the height of a man,” an official German pamphlet notes. The statues themselves are a bit larger than life-size, kneeling figures of a man and a woman who look down from a pair of rough stone pedestals: The Mourning Parents. This is not the usual sort of martial monument, but perhaps the Belgians wouldn’t have allowed one. Perhaps, too, the diplomatic skids were greased by the fact that the figures were carved in Belgian granite. A blue gray stone, it is not a true granite but is durable enough. The statues have been placed side by side–everything is so symmetrical here–as if contemplating the skylights from that defunct workshop of Mars. (In Cologne, another version of the Parents, executed posthumously, is angled so that the two figures half-face each other, giving an effect of intimacy that I missed at Vladslo.)

The two figures are recognizably Kathe Kollwitz and her husband, Karl, the artist and the working-class doctor from Berlin, each possessed of a saintly single-mindedness–in stone as in life, curiously connected and curiously remote, an enduring mismatch. Here are two people perched on the edge of a chasm of sorrow, trying to pull back before it is too late. Wasn’t it Nietzsche who said that if you stare into a chasm long enough, the chasm will begin to stare back at you?

Kathe Kollwitz always chose her models close to home, mostly because she couldn’t afford professionals. Karl’s face is all detail; Kathe’s, less face than efface: In grief as in everything else, women had their place in those days. Around his full, downwardly sloping lips, lips that seem on the verge of a tremor, deep lines incise melancholy parentheses. His nose is long and bony; Death’s head shows through those features. His eyes, half-closed, seem focused inward, as if filled to brimming with the second sight of memory. An optical illusion? They are unforgettable. He is a man locked in a prison of grief. Could that explain the lank hair and the loose tunic that might almost belong to a convict?

Beside him, wrapped in a shawl, his wife stares at the ground, her chin sunk into her chest and, in contrast to his severely upright posture, her shoulders slumped. Her hair is pulled back to form a kind of skullcap, emphasizing the familiar wide Kollwitz nose, the heavy-lidded eyes, the broad boned face-that prematurely old face, its fresh and resilient youthful contours long gone, “that place of suffering” one acquaintance called it.

They kneel, their arms folded against their bodies, hugging themselves as if to ward off a palpable chill, one that would not disappear in their lifetime.

Only in my own has it begun to lift.

You might as well say it: Peter Kollwitz is pretty much a cipher, an unperson. Only a few photographs survive. He had his mother’s full mouth and prominent nose, his father’s long face. Intelligence and a likable wryness are written over that countenance; bad luck is not. There is a final snapshot taken just three weeks before he was killed. In his tunic and field cap Peter slouches against a barracks wall; he holds a cigarette with studied nonchalance. Underneath the youthful bravado, though, you sense a certain edgy vulnerability, as if aware of a future suddenly become finite.

Kathe Kollwitz’s diaries have survived, but they are chiefly valuable as records of her moods (mostly depressed) and the progress of her work; they tell us little about Peter. It’s not easy to re-create a personality out of her reactive vision: Hers was an art of one-sided confrontation; everything was seen from the point of view of the sufferer. Peter now exists mainly as a reflection of his mother’s grief. In that sense he is a universal soldier, more universal, perhaps, than The Mourning Parents, who were supposed to be just that.

We are left with a smattering of clues to his nature. He was born in Berlin in 1896, while his mother was working on a series of prints about a weavers’ uprising; they earned her a gold medal, which the kaiser vetoed, calling them “art from the gutter.” We hear Peter’s voice only once. In 1903, when he was seven, Kollwitz was beginning an etching called Woman with Dead Child. She held Peter across her lap, glancing up at a mirror while she sketched. She groaned from the effort. “Be quiet, Mother,” the boy said, “it is going to be very beautiful.” Years later she would call the finished etching prophetic.

Like all the Kollwitzes and most young Germans of his time, Peter was a prodigious hiker. He and his older brother, Hans, who became a doctor like his father, staged amateur theatricals. He was a collector–but then, most teenagers are. In his room he kept a cupboard full of stones and a head of Jarcissus, which he may have picked up during the months he had once spent with his mother in Italy. He showed talent as an artist, and was obviously the favorite of her two sons. After his death she took to sleeping in his room.

When war was declared, the Kollwitzes were in Konigsberg, he Baltic town in East Prussia where she had been born in 1867. “I remember hearing the departing soldiers singing as they marched past our hotel,” she wrote later. “Karl ran out to see them. I sat on the bed and cried, and cried, and cried. Even then I knew it all beforehand.”

Peter, who was 18, rushed to volunteer. His wild outpouring of enthusiasm for the war briefly convinced his mother. Everyone was stuck on the notion of sacrifice and the Death of the Hero. Heroism was the enchanted word that united an unstable nation, one in which the distinctions and divisions of class were deep and bitter. Rivers of heroes’ blood, one poem proclaimed, would flow homeward and revitalize the nation. “Rushing off to war,” as the historian Robert Wheldon Whalen points out, “was an act of love.” Peter Kollwitz was no exception. “It always strikes me as strange,” his mother later wrote, “when masses of young people profess to be pacifists. I simply don’t believe them. All it takes is one spark falling among them, and their pacifism is forgotten.”

For the record, Peter Kollwitz served in the Fourth Company in the 207th Infantry Reserve Regiment in the Forty-fourth Reserve Division in the Twenty-second Reserve Corps in the Fourth German Army. The sense of unit anonymity builds. His mother made one last visit to his army barracks and listened to a sermon blessing the departing volunteers. She gave him a flower before she left, a pink.

His division entrained for the Western Front in mid-October and went into action at Dixmude on the 22nd, a day when the Battle of the Yser River was approaching a crisis. The first Germans had pushed across the tiny stream and were threatening to pierce the last Allied line of resistance. Peter’s division was still on the other side. There had been showers throughout the day and heavy fog. The Forty-fourth Reserve Division was ordered to cross that night. Bullets whistled indiscriminately, haystacks caught fire, and Dixmude was in flames. The shellbursts reminded one French marine officer of thunder in a summer storm just before the rain falls. Wild firing broke out; officers couldn’t keep control, and the attackers gave themselves away. Men overran enemy trenches, burst into loud hurrahs, and stopped. Units became mixed with other units; headlong attacks were followed by interludes of milling around. The attackers were in turn taken from the rear. By daylight–”that great friend of humanity,” the French officer called it–the Germans were back where they had started. Sometime during those hours, Peter Kollwitz had been killed, the first man of his regiment to die.

When we next hear from Kathe Kollwitz, it is November; the Yser is, for Germany, another lost opportunity; and she is writing to two friends:

Your pretty shawl will no longer be able to warm our boy. He lies dead under the earth….He did not suffer.

At dawn the regiment buried him; his friends laid him in the grave. Then they went on with their terrible tasks. We thank God that he was so gently taken away before the carnage.

Please do not come to see us yet….

“He did not suffer.” This decorous euphemism for home consumption generally meant one of two things: Either a bullet had struck a man in the head or else a shell had blown him apart. Kathe Kollwitz was still swallowing the party line, as it were, on sacrifice. Maybe it was the only way she could cope with Peter’s death at first. She was not yet ready to go public with her deeper feelings.

Grief such as she experienced was another, less reported part of the Western Front story, and it was woven like a black band into the fabric of subsequent European history. People were unprepared for so much loss, loss that left few untouched. There was an eerie, offstage quality about all that dying. (The same thing had happened in other wars, of course, but never on such a vast scale.) Men boarded a train or waved goodbye at a barracks gate, and disappeared forever. No wonder survivors could remember the day, the hour, the weather, the last words exchanged, with such clarity.

That unreality was underscored by the way you found out that your husband or son had died–”gone west” was the soldier’s phrase. If you were lucky, an official letter or telegram brought you the news. But sometimes you simply glimpsed the name of a loved one on a huge casualty list posted on a city wall, or your last letter to the front came back to you stamped “Dead–Return to Sender.” People reacted with bewilderment and, only much later, resentment. They were even denied the purging ritual of a funeral. (In that respect the recent American custom of shipping war dead home, often to be viewed in an open coffin, is healthy. But even American ingenuity would be hard put to return hundreds of thousands of bodies.)

There was nothing remote about the aftereffects of loss. Soldiers, as has been pointed out, were not the only war victims. They included the women reduced to poverty by the death of a husband and wage earner; the children left to roam wild while their mothers worked; the families broken apart; the parents deprived not just of the consolation of heirs but of support in their old age; the intellectual and political movers and shakers stripped of their imaginative energy, their power to persuade. Considered in this light, the phrase home front takes on new meaning. “First he fell in battle,” she wrote, “and then I did.” So much of 19th-century optimism had been founded on a belief in the future, and for millions that was gone now.” I walk in half-darkness, there is seldom a star, the sun has set, long ago and forever.”

Grief, spread wide enough, and the anger that inevitably follows, can be an unspoken ingredient of social breakdown, a negative force; and the paralysis it brings, a very real affliction. For years after Peter was killed, Kathe Kollwitz produced hardly anything. As she wrote, and she was not talking only about herself: “If all the people who have been hurt in the war were to exclude joy from their lives, it would almost be as if they had died. Men without joy seem like corpses. They seem to obstruct life.”

These words come from Kollwitz’s diary, and were written in March 1918, when the worst was behind her. That diary can be read as a fever chart of her grief, and of her growing opposition to war. More important, in those papers she has left us a record of the conception and painful execution of the statues at Vladslo, which would consume her for 18 years, the span of Peter’s own life.

She began bravely. “Conceived the plan for a memorial for Peter tonight,” she wrote on December 1, 1914, “but abandoned it again because it seemed to me impossible of execution.” At 47, she was new to sculpture and was not yet sure of her skills. But the next morning the idea was back, and now she was thinking of asking the city of Berlin to donate a place for the memorial, to commemorate the deaths of all young volunteers, on heights overlooking the lake called the Havel. “The monument would have Peter’s form, lying stretched out, the father at the head, the mother at the feet.” Several days later the design seemed to take clearer shape.

My boy! On your memorial I want your figure on top, above the parents. You will lie outstretched, holding out your hands in answer to the call for sacrifice: “Here I am.” Your eyes–perhaps–open wide, so that you see the blue sky above you, and the clouds and birds. Your mouth smiling. And at your breast the pink I gave you.

But there was little indication of progress during the next months: Grief, like the damp, catarrhish chill of a Berlin winter, had settled in. “The idea of eternity and immortality doesn’t mean anything to me at present….When one says so simply that someone has ‘lost his life’–what a meaning there is in that–to lose one’s life.” And: “Recently Karl said, ‘His death has made us no better.'” Her project seemed to be floundering. On February 21, 1916, the day the Germans attacked at Verdun, she noted, with no great optimism, “Perhaps the work on the memorial will bring me back to simplicity.” But she reported on March 31 that she was

overcome by a terrible depression…When I am in the midst of artists who are all thinking about their own art, I also think of mine. Once I am back home this horrible and difficult life weighs down upon me again with all its might. Then only one thing matters: the war.

Now it was mid-April, a time when Peter’s regiment, the 207th Reserve, was being chewed up in the Mort Homme sector of the Verdun front. “Worked. I am making progress on the mother.” But another summer came, the summer of the Somme–Peter’s regiment suffered cruelly there, too–and still nothing went right: “Stagnation in my work.” She told of making a drawing in which a mother lets her dead son slide into her arms. “I might make a hundred such drawings and yet I do not get any closer to him.” Peter, she was convinced, was “somewhere” in her work, and yet she could not find him. Was it worth going on? “I have the feeling that I can no longer do it. I am too shattered, weakened, drained by tears.”

Two years after Peter’s death, Kollwitz was touching bottom, and the next pages are painful to contemplate. “My work seems so hopeless that I have decided to stop for the time being. My inward feeling is one of emptiness….Talking to people means nothing at all. Nothing and no one can help me. I see Peter far, far in the distance.”

As Peter’s image receded, so did the ideal of sacrifice. A new theme would come to dominate: the futility of this war, of all wars. Suddenly she was writing not of her own paralysis but of a paralysis of “this frightful insanity–the youth of Europe hurling themselves at one another.” She recalled that last day at the barracks outside Berlin and the sermon that a minister had delivered before a final blessing of the volunteers:

He spoke of the Roman youth who leaped into the abyss and so closed it. That was one boy. Each of these boys felt that he must act like that one. But [she would write in October 1916] what came of it was something very different. The abyss has not closed. It has swallowed up millions, and it still gapes wide. And Europe, all Europe, is still like Rome, sacrificing its finest and most precious treasure–but the sacrifice has no effect.

Kollwitz was giving in to stranger feelings, though, the sort that must have been shared, and occasionally acted out in pathetic conjurations, behind closed doors everywhere as the heaven of an old world tried to strike a deal with the oblivion of a new. She contemplated a reunion with Peter’s spirit: “I can hope …that when I too am dead we may find ourselves in a new form, come back to one another, run together like two streams.” She claimed that she could often sense his presence: “He consoles me, he helps me in my work….I am aware of him approving or rejecting, glad or sad.”

Kollwitz looked back at other signs, or what seemed like signs. She thought Peter must have exerted some mysterious sway over his brother, Hans, at the moment he died: That was the night when Hans decided to go into the Medical Corps and not into the infantry. And “Wasn’t it a sign when on October 13″–the date on which he had left for the front–”I visited the place where your memorial is to stand, and there was the same flower that I gave you when you departed?” Theosophists, she noted, maintained that you could train your faculties so that you could feel your way “toward that other world.” Was it then possible to establish such a connection–or was it just “an intellectual jest?”

It is common for people at home to experience similar clairvoyant “signs.” Conan Doyle received “messages” from his brother-in-law, killed in the retreat from Mons in 1914; they played a part in his conversion to spiritualism the following year. His eldest son and his brother served on the Western Front, and also died. Doyle’s belief in an afterlife seems to have made their losses easier to bear. “You might laugh at me because of this,” a German woman wrote, “but my husband and I had promised each other that if one of us died anywhere in the world without being able to tell the other, the one who died would somehow contact the one still living.” He left for the front, and one night she dreamed that she saw him. “As he came closer, I awoke with a terrible scream, since what was staring at me was a death’s head.” Not long after, she received the notification that she expected. Some hours before the dream, her husband had been killed.

By 1917, the year of her 50th birthday, Kollwitz seemed to have put the worst behind her. “I work without effort and without tiring,” she wrote at the end of July. “It is as if a fog had lifted.” She felt there was a chance of finishing the plaster cast of the woman that fall; then work could be started on the final, stone version. (This big work still included a figure of Peter, wrapped in a blanket, only the head left free.)

She learned that Peter’s body had been dug up from its solitary grave and reburied in a so-called concentration cemetery at Eessen-Roggevelde, a couple of miles east of Dixmude. (It would not be the last journey for those poor bones.) In addition to the major sculpture group destined for the Berlin hillside, Kollwitz now thought of doing a life-size relief in stone of the grieving parents; it would be placed at the entrance to the cemetery, with some short but suitable inscription engraved on it. She toyed with various possibilities: “Here lies German youth”–or simply, somberly, bitterly: “Here lie the young.”

Depression overtook her, as it had so often in the past. The mother was still uncompleted. In October, Kollwitz returned from vacation, but when she went to work again, she “felt no sense of refreshment at all. On the contrary, I’d lost the conception; everything was trite. I let the mother alone for a while, took up the clay figure of the father, and then dropped it too.” Now she was resigned to the possibility that it might be years before the sculptures were done.

But then, as the country headed for the “turnip winter” of 1 917-18, depression was general. Cracks were beginning to appear in the military facade, too. Ypres was turning into an unimaginable horror. The new division that Peter’s regiment now belonged to had been so roughed up at Verdun that it had to be pulled out of the line and reorganized. The men in at least one replacement unit in Germany refused to leave for the Western Front, and their mutiny was apparently tolerated. The French mutinies are well known, and at least one major disturbance erupted behind the British lines. But there are indications, ever so faint in the records, that the Germans also had to deal with soldier insurrections in 1917.

From then on, work on the statues went forward in a halfhearted way, if at all. But Kollwitz’s drawing, which she had pretty much given up in the last years, was another matter: “Curious how the sluices are opening up again,” she noted on December 17, 1917. The need to end the war consumed her thoughts. She was overcome by the feeling that by ” letting them go simply to the slaughterhouse,” she had betrayed her sons. “Peter would still be living had it not been for this terrible betrayal. Peter and millions, many millions of other boys. All betrayed.”

That was her entry for March 19, 1918. Two days later, the German supreme commander, Erich Ludendorff, would take the first of his gambles for victory on the Western Front, the great offensive in Picardy. By the time it ground to a halt, after an unheard of gain of 40 miles and the beginning of the end of trench warfare as it had been known for three and a half years, Peter’s regiment would be so weakened that it could hold no more than 160 yards of front. One thing is clear: Even if he had survived the Yser, Peter Kollwitz would have had plenty of other chances to die.

“Germany is near the end,” his mother wrote on October 1, 1918. “Wildly contradictory feelings. Germany is losing the war.” It seemed madness to continue fighting. Toward the end of that wild month, the poet Richard Dehmel published a manifesto which he called on all fit men to volunteer for a last stand to save Germany’s honor. Kollwitz immediately “penned a reply, taking passionate issue with him. Those men, she pointed out, would consist mainly of boys in their teens, the same age group that had died so plentifully in 1914. How could the nation any longer justify the deaths of the very “people on which its future depended?” In my opinion such a loss would be worse and more irreparable for Germany than the loss of whole ”

It was a view that geneticists might agree with–though considering the history of the next quarter century, you might be tempted to add that too many of the best had gone already. There has been enough of dying!” Kollwitz wrote. “Let not another man fall!” And she quoted the words of Goethe:

“‘Seed for the planting must not be ground.'” A few days later, the Great War would be over, but not before the grinding of more planting seed.

It was as if Kollwitz, like her own country, had weathered a terrible illness: The crisis had passed, but a debilitating weakness remained. For her, as for Germany, that illness, the war, had become an obsession; her very inspiration depended on it. The following summer she took what may have been an inescapable, and certainly purging, decision: She abandoned her big work. “Tomorrow,” she wrote on June 25, 1919, “it will all be taken down.” She stood by the scaffold regarding Peter’s face and then kissed the cold clay of his effigy. “I thought of Germany. For Germany’s cause was his cause, and Germany’s cause is lost now as my work is lost.”

Two years went by. On the seventh anniversary of Peter’s death, Kathe Kollwitz sat alone in his room, the room where she now slept alone, and stared at the cupboard still full of his stone collection. She could barely remember how he had looked. “His image is dissolved, even as his body has become wholly earth”–smudged by the clumsy eraser of time. There were compensations: The anguish of bereavement had vanished, too.” I am glad to be alive, intensely glad when I can work…”

The story could have ended here, on a slightly upbeat note, but it didn’t, of course.

I always imagine Kathe Kollwitz in shades of black and white; not even in her little studio room next to her husband’s dispensary was there a hint of color. Color did not become her. But her monotones were as bright as any primary, and became brighter as the war receded. The twenties were a rich period for her art. Her suffering mothers, her child victims, her hollow-eyed fraternity of the proletarian dispossessed proliferated. There was a new and fearful simplicity to her graphics, an eschewing of detail that yet hinted of deeper complexities: a highly politicized art that rose above politics. The abyss does stare back at us, and the result still has the power to unsettle. You can write it off to a maturing command of technique and the old artist’s impatience with fussy detail. But had something else been liberated after the long dry spell of grief, like a dark flower blooming in a desert of chalk?

It was a good time for other reasons. Kathe Kollwitz was glad to be alive. She grew closer to her husband. Karl had brought her through the crisis of Peter’s death, and his quiet strength, more than anything, seems to have cemented their uncertain union. They traveled to Russia. Though she was much acclaimed there, she would never embrace communism, which she found too intrinsically warlike. She delighted in her four grandchildren. (The eldest was named Peter, and he would die on the eastern front in the next war, hardly older than the uncle for whom he was named.) Occasionally she would unwrap the figures for the memorial, only to cover them once more. And then one day–her diary indicates that it was in October 1925, just before the mournful anniversary came round for the 11th time–she went back to them.

Even at this late date, she still had two distinct works in mind: the major memorial complex for Berlin and a more modest monument for the cemetery at Roggevelde. Perhaps that grandiose scheme, so alluring in concept, so difficult in execution, had been one of her troubles all along. Although she had simplified her design for the latter, taking the kneeling figures of the parents out of relief, it sometimes seemed that she was almost willing herself not to finish. There were mishaps that a psychiatrist might not find curious. In a period of only a few days, she twice knocked the figure of the mother off its turntable and had to reconstruct completely what she had destroyed.

June 1926 was another important date for Kathe Kollwitz. That month she and Karl made their first visit to Peter’s grave. From this point on, her energies would be devoted to one monument only: The Mourning Parents.

Kathe and Karl Kollwitz boarded one of those trolleylike local trains at Dixmude, rode south a few miles, and then set off on foot. Hedges had already grown up along the road, though as yet few trees; they could see fields beyond and an occasional brick farmhouse, already rebuilt. The war was still in evidence. There were dugouts everywhere. A creepy rural silence enveloped them, though she noted that “the larks sing gladly.”

This was a scene repeated countless times in those years. The hesitant and perplexed elderly parents or the widows with children grown into their teens searching for the right grove of crosses–too often it was a forest–with its predictably monotonous rows of soldiers’ graves. These stragglers rarely came in busloads, like the British to Ypres or the delegations of Gold Star Mothers from America, and they were careful not to give offense in the land of the victors.

They could be hindered, too, by their inability to speak the language. I think of that German guidebook to the Western Front, which gives key phrases and sentences, with their equivalent in French: Driver! Are you free? Can you take me to cemetery X? How much do you charge? In what part of the cemetery can I find grave number…? Do you know the address of a photographer who can take a shot of it? Where can I purchase a wreath? Waislder Preis? Que! est le prix?…

The Kollwitzes found themselves lost in a flatland labyrinth, a wizardless Oz, even as I would decades later at Vladslo. Finally a friendly young peasant led them to an opening in a hedge, bent aside some strands of barbed wire that blocked it, and left them alone. “What an impression: cross upon cross.” Roggevelde was actually medium-size as Western Front cemeteries went, with only 855 occupants. The Kollwitzes soon located Peter’s cross, low, tin, and marked like all the others with a metal identification plaque–a kind of dog tag of the dead. She described the scene in a letter to Hans:

All that is left of him lies there in a row-grave. None of the mounds are separated: there are only the same little crosses placed quite close together… and almost everywhere is the naked, yellow soil. Here and there relatives have planted flowers, mostly wild roses, which are lovely because they cover and arch over the grave and reach out to the adjoining graves which no one tends, for to the right and left at least half the graves bear the inscription allemand inconnu.

They cut three roses from a wild briar and placed them at the foot of Peter’s cross.

Kathe Kollwitz immediately set about looking for the best place to put her figures. They would not fit amid the graves; the rows were too close together. She decided that she would like to place them just across from the entrance, where “a kind of garden plot” was now laid out. “Then the kneeling figures would have the whole cemetery before them.” The mourning parents left, walking back to Dixmude.

She had one further happening to report to her surviving son. “Tonight,” she wrote, “I dreamed there would be another war….”

From now on, nothing mattered quite as much as the memorial for Roggevelde. “It is beginning,” she exulted on October 22, 1926–that day again–after a helper had built up the scaffolding and clay for the figure of the mother. “I feel as if I now stand directly before the last stage of my work.”

But completion still eluded her. Another year went by, and then three more. She ran into technical problems–on, of all things, clothing. “The naturalistic folds disgust me and the stylized folds disgust me.” (In the end she struck a successful bargain between the two.) Advancing age and diminishing physical capacities haunted her. “Sixty years old–how can I manage to do anything important anymore?” (She underestimated her staying power; she would live another 17 vigorous years.) She worried that the father figure “had no soul” and she tried crossing his arms over his chest. (That was her eventual, and utterly moving, solution.)

She also experienced moments of undeniable inspiration. An acquaintance was sitting for her, modeling for the head of the mother. Kollwitz suddenly realized that the face was all wrong. She dug out a self-portrait in plaster and unwrapped the head. “It was as if the scales fell from my eyes. I saw that my own head could be used after all.” Of course. Could the mother have been anyone else but Kathe Kollwitz?

In April 1930 two friends visited her studio, and Kollwitz did something she had never done in all the years of work on her memorial to Peter: She showed the two figures, nearly completed in clay. “The figures seemed to make the impression I had hoped for.” She felt “agitated…euphoric”–and then (this is pure Kollwitz) was overcome by “dull indifference.” But she had gone too far now not to finish.

Still, it took exactly a year more before she actually exhibited the sculptures of The Mourning Parents, in plaster, at the Prussian Academy of the Arts, Germany’s most esteemed cultural institution–where she was now head of the Department of Graphic Arts. (Two years later the Nazis would force her out, and she would never again be allowed to exhibit her work in Germany.) She was pleased with the acclaim the figures received from her fellow artists. All that remained was to have them converted to stone. She was in the final stretch, truly and at last, starting work with two sculptor-masons, one for the mother, the other for the father. “In the fall–Peter– I shall bring it to you.”

But for Kollwitz, things were never quite so easy. The year 1931 passed. Now events were catching up with her. These were the months when Japan invaded Manchuria; the Kreditanstalt failed, bringing the banking system of central Europe down with it; Herbert Hoover made his vain, gallant attempt to head off the spread of worldwide depression by seeking a moratorium on German war debts; the unemployed were gathering around Berlin in tent cities organized with military precision; and, like trench raiders bursting out of the shadows the Nazis were closing in on power. “The misery,” Kollwitz noted in her diary, “People sinking into dark wretchedness the repulsive political hate-campaigns.” The armistice was proving to be just that–not an end but an intermission in fighting.

The state of Prussia had, at the end, given Kollwitz a grant yo help pay for the conversion to stone. It hardly covered her expenses, but the state did arrange to waive toll and freight harges to Belgium, and the German war -graves people sup lied the foundation s and pedestals. The Roggevelde cemetery had changed since the Kollwitzes visited six years earlier. The mall tin crosses had been replaced with low, thick, wooden ones, all alike, and the rows had been straightened out, to run with perfect regularity and cover a rectangle that was now walled in. “Only three graves are planted with roses. On Peter’s grave they are in bloom, red ones.” (This is one of her few references to color. It also indicates two things: that the number of visitors was diminishing–and that someone must have put in a bush for the benefit of the Kollwitzes.) She found the whole effect of the improvements a bit monotonous. But then, she reflected, “a war cemetery ought to be somber.” It took two days to set up the figures and to make sure that they had the proper forward view. As the workers lowered the father onto his pedestal, she experienced a moment of dismay: His line of vision was too low; instead of looking out over the graves, he seemed to be staring downward, brooding, as if too much caught up in his own thoughts, his private grief. No amount of raising and adjusting could change it. Kollwitz left, “sad rather than happy.” Had 18 years of work come down to a misplaced glance?

The next morning, a Friday, she packed. It rained. Memorial rain. All along the old front line-Scott Fitzgerald’s words are suddenly apt-“infinitesimal sections of Wurtemburgers, Prussian Guards, Chasseurs Alpins, Manchester mill hands and old Etonians” pursued “their eternal dissolution in the warm rain.” Forever young-though for the record, Peter Kollwitz would have been 36 in July 1932, on the threshold of middle age. Around four in the afternoon, a war-graves caretaker came round with a car and drove the Kollwitzes out to the cemetery. The skies had cleared. Her depression of the previous day had “lifted.” She was, she now reported, “able to see it all in the right light.” Of course: That downward, inward look of the father is precisely what gives his face the power to haunt. The war-graves man withdrew discreetly; the old couple approached the statues. Kathe Kollwitz seemed to know that she would never see them again.

“I stood before the woman , looked at her-my own face and I wept and stroked her cheeks. Karl stood close behind me–I did not even realize it. I heard him whisper, ‘yes, yes.’ How close we were to one another then!”

Postscript: Peter Kollwitz’s posthumous travels were not quite over. At the time The Mourning Parents were erected, there were 128 German burial grounds in Belgium, ranging from single graves to clusters of thousands. But after the Second World War, the Belgian government demanded that the Germans consolidate them into four cemeteries of several acres each. The pressure of an expanding live population was the reason given. So, in the 1950s, Peter Kollwitz’s remains (a curiously cold and remote word , that) were moved to an existing cemetery at Vladslo. The statues came too, along with the bones of almost 22,000 men from all over Belgium. You can find Peter Kollwitz in the back row, slightly to the left of his mother’s figure, sharing a stone with thirteen others.

“Since it was impossible to keep bones separate during exhumation,” a German war-graves official remarked, “they could not be buried in individual graves.” There could be less efficient ways, I suppose, of creating a universal soldier.

Now, the shadows of early evening thickened and spread, enveloping that cheerless Vladsloglade–those same creeping shadows that Kathe Kollwitz always, but imperfectly, managed to keep at arm’s length. As I was about to leave, a middle-aged couple approached The Mourning Parents. They were speaking in hushed German–there is nothing about this place that encourages a natural tone of voice. The woman was dressed in a yellow, short-sleeved blouse and bright red slacks, a still trim figure in her traveling uniform. Kathe Kollwitz must have been about her age when Peter was killed. She carried a bouquet of crimson roses wrapped in a shroud of stiff cellophane; her husband had a camera around his neck. She peeled off the cellophane and handed it to him. He folded it neatly, tucked it into his trouser pocket, and motioned to his wife to stand between the pedestals. She cradled the roses as if presenting arms. He brought the camera to his eye, she stiffened, and the mirror of his single-lens reflex banged back with a sound that reverberated through that dead space. Then, still for the benefit of the camera, she placed the roses on the flagstones in front of the statues. There hardly seemed enough light for a picture, and yet he continued to snap away. It sometimes seems that we spend our lives denying the night.

“Pain,” as Kathe Kollwitz once wrote, “is very dark.”

This article originally appeared in the Autumn 1990 issue (Vol. 3, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: The Mourning Parents