“Gentlemen, we want your money.” In retrospect, it was an unnecessary statement, as their masks and guns made manifest the men’s intentions. Anyway, passengers had heard the gunshot from up toward the express car. It had been the last sound the unfortunate express messenger would ever hear.

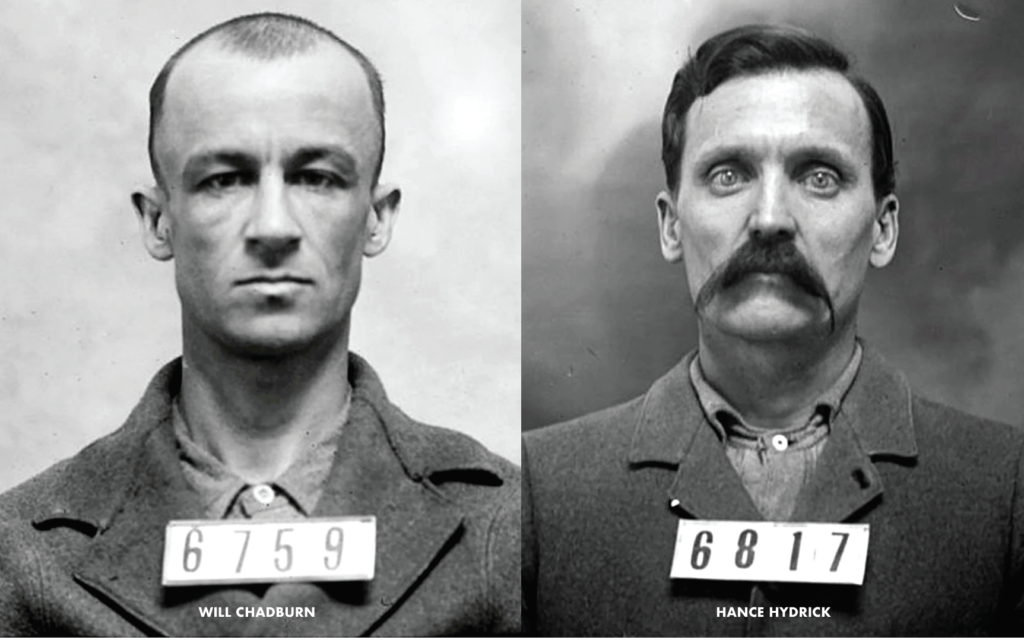

Will Chadburn was on the dodge by late August 1893. He’d committed a string of crimes in and around his hometown of Sedan, Kansas, apparently seeking to justify his adopted nickname, “Billy the Kid.” In quick succession, he’d robbed a train conductor of a fine watch and chain, stolen a horse, held up a store, shot up the town, robbed two more citizens along the road, then fled east into neighboring Montgomery County. While lying low outside Coffeyville, waiting for pal Bob Dunn (his probable partner in the store holdup) to return with supplies, Chadburn happened across fellow fugitives Hance Hydrick and Claude Shepherd.

They were on the run from Pine Bluff, Arkansas, where Hydrick had bludgeoned a livery stable owner to death and Shepherd had been pinched for burglary. The pair had escaped from the Pine Bluff jail along with four other inmates on August 15, leaving a note in their cell warning they were “heavily armed” and promising a “warm reception” for any lawmen who dared pursue them.

Recognizing kindred spirits, Chadburn asked Hydrick and Shepherd if they’d like to “turn a trick” that would bring them cash. According to a later confession by Shepherd, the partners were intrigued, so Chadburn suggested they all meet a few days later at Caney, some 18 miles west, to go over the details. Chadburn and Dunn then left. Hydrick and Shepherd, with only a .32 pocket revolver between them, felt woefully undergunned for what Chadburn had in mind, so they slipped into Coffeyville to purloin additional arms. With tools stolen from a wagon shop they burglarized the Isham brothers’ hardware store, making off with two Winchesters, several pistols, a few hundred cartridges and about $20 in cash.

Arriving in Caney, they found only Chadburn, as he and Dunn had had a falling out. Chadburn outlined his scheme to rob the eastbound St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (aka “Frisco”) train at Mound Valley, in Labette County, 17 miles northeast of Coffeyville. After holing up a couple of days with friends farther west in Chautauqua, the trio started off. They traveled by night and soon abandoned their stolen horses out of paranoia. Finally reaching Mound Valley after dark on September 2, they hid in a ravine east of town to await the train. As it came chuffing down the track around 12:50 a.m. on the 3rd, the would-be bandits’ initiated their robbery attempt, which went comically awry. They’d built a bonfire on the tracks to flag the train, but the engineer stopped closer to it than anticipated, forcing the hapless highwaymen to scramble along the tracks to catch up. Before they could reach the express car, the crew had the track cleared and the train moving again. It soon disappeared into the night.

“Disappointed but not discouraged,” the Oswego Independent later reported, the trio walked to the Mound Valley depot to await the westbound Frisco, scheduled to arrive around 3:30 a.m. This time when the train rolled to a stop, they were in position. Chadburn mounted the locomotive to hold the engineer and fireman at bay while his partners tackled the express car. What exactly took place there is uncertain, as the only surviving witnesses were the robbers themselves. According to Shepherd, express messenger Charles A. Chapman, a 24-year-old newlywed, refused to give up without a fight and apparently tried to seize the outlaw’s rifle, receiving a bullet through the head for his trouble. Unable to open the safe (a through safe with a time lock the messenger himself couldn’t have opened), the bandits elected to plunder the passengers.

After tossing Chapman’s body out onto the platform, Hydrick and Shepherd joined Chadburn aboard the locomotive and directed engineer Ollie Shaffer to pull a half-mile farther down the tracks. The trio then escorted Shaffer and his fireman back to the passenger coach and announced their intentions to the startled travelers. Hydrick and Shepherd, masked with bandannas and carrying Winchesters, guarded either end of the car, while Chadburn, wearing no disguise but a slouch hat pulled low, went to work. Brandishing a revolver, he paced the car and demanded passengers “shell out.” He collected their money and valuables in an oilskin sack.

While his cohorts were businesslike, Chadburn seemed to enjoy himself, bantering with some victims and menacing anyone who resisted. James M. Kelly from Haverhill, just east of Wichita, managed to squirrel away $15 in bills and offered up a wallet containing just $2 in silver. Forced to surrender his pocket watch, Kelly pleaded to keep the chain, which he explained had been a gift. “No, hand it out,” Chadburn replied with a smirk. “We need it in our business.” James W. Brown, a Frisco agent from Haverhill, tried to sneak his watch and chain to his wife, but the sharp-eyed robber caught him and took both items along with $3 in cash. When another man balked at giving up his goods, Chadburn threatened to pistol-whip him, growling, “Get that money, or I’ll bust your head.” The man surrendered a wad of greenbacks hidden in his shoe. Adding insult to injury, Chadburn took the victim’s shoes as well. He forced another reluctant young man to surrender his coat and vest along with his cash. A married man reluctantly parted with a ring his wife had given him, while another passenger lost his revolver to the oilskin bag.

With others Chadburn was almost jovial. When an old man asked if he had any “chew,” the bandit obligingly produced a plug. The codger bit off a chunk and moved to pocket the rest. “Hold on there,” Chadburn told him. “The damned marshals will be chasing us all day tomorrow, and I don’t want to be without tobacco.” Such antics seemed to annoy his partners. One of them, witnesses said, urged Chadburn to not waste time in idle chatter with the passengers. “Hurry up!” the nervous cohort warned. “It will be burning daylight pretty soon.”

One passenger spared Chadburn’s attention was Wichita Police Chief Rufus Cone, who was riding in the adjacent sleeper car. Awakened and alerted by the conductor and porter, Cone grabbed his .38 Smith & Wesson revolver and with the trainmen headed toward the passenger car, the porter also armed with a .38. As they reached the connecting door, Cone later claimed, he was preparing to fire through the glass at the nearest robber, whose back was to him, when the conductor warned him the pane was three-quarters of an inch thick and would likely render his shots ineffective. Cone also noted Chadburn’s “big revolver” and the two Winchesters. “When I saw their guns and looked at mine and the porter’s,” he later told The Wichita Daily Eagle, “ours seemed to be no bigger than toy pistols.” Exercising the better part of valor, Cone’s party retreated to the sleeper, where the porter doused the lights, and he and Cone took defensive positions. Shortly after, Cone said, one of the robbers tried the door but was stopped by one of his partners, who said it was time to go.

Chadburn made one last act of bravado, returning the passenger’s pistol he’d collected, then Cone and the others watched the three outlaws crest a nearby hill afoot and disappear into the predawn gloom.

The September 3, 1893, robbery and murder of Chapman made front-page news. The Oswego Independent declared the holdup, “One of the boldest and most daring train robberies that has ever occurred in Kansas,” while The Wichita Daily Eagle speculated it was “not at all improbable” the perpetrators were members of the notorious Doolin-Dalton Gang (aka “Wild Bunch”). Newspaper accounts from Mound Valley shared space with reports of that gang’s bloody shootout two days earlier with a posse of U.S. marshals at Ingalls, more than 100 miles southwest in Oklahoma Territory.

Chief Cone drew heavy press criticism for his decision not to engage the robbers. “He and the Negro porter,” the Lawrence Weekly World chided, “of all the trainload were armed, and they offered no resistance whatever.” The Sedan Times-Journal was particularly harsh. “Rufe Cone, chief of police of the city of Wichita, is a brave man,” it wrote. “He stood by, heavily armed, and saw the murderers of express messenger Chapman rob the passengers on the Frisco train at Mound Valley and never turned his hand toward preventing the outrage.” Sedan’s own lawmen, the paper fumed, “would have killed or arrested the three men in just three minutes, but then they are not populist statesmen, only plain Republican peace officers who think it their duty to protect the lives and property of their fellow citizens.”

Cone deflected such barbs with humor, telling The Wichita Daily Eagle had he been in the passengers’ shoes, “I think I would shell out to them everything I had and apologize for not having any more.” He added that wherever he next traveled, “I’ll take the biggest revolver I can find.” The Eagle couldn’t resist a parting shot at its hometown lawman: “Chief Cone, to ease his friends at home Sunday, telegraphed that he lost nothing but his nerve and that he was lucky enough to find that after the robbers had gone away.”

Not all newspaper accounts were dedicated to second-guessing Cone. “The prompt retreat of the Mound Valley train robbers to the Indian Territory [part of present-day Oklahoma],” The Kansas City Times speculated, “indicates that they know full well where safety lies.” The territory’s bordering states, it railed, were “tired of having their good name maligned by the succession of Daltons, Starrs, Kid Wilsons and whatnots.” The newspaper blamed both the U.S. government and “the irresponsible Indian governments” for allowing the territory to become a “ready haven” for such desperadoes.

Despite news reports, the outlaws didn’t immediately flee into the territory. In fact, they backtracked through Mound Valley, camping in the brush west of town. The next morning they divided their swag, which wasn’t much: a reported $32.60 each in cash, a handful of watches, chains and assorted jewelry, and the few items of clothing. After nightfall, they followed the tracks 10 miles northwest to Cherryvale, where Hydrick and Shepherd stopped in at a restaurant for a meal and picked up local gossip about the robbery. Bringing lunch out to Chadburn, they settled in till nightfall and then hiked due south. They hid in the woods all the next day, then resumed their flight south toward the territory.

Reaching Coffeyville around 4 the next morning, they headed to the Missouri-Pacific Railroad depot and clambered aboard a grain car on a train waiting to cross Indian Territory into Arkansas. They bedded down, expecting to wake in Van Buren, across the Arkansas River from Fort Smith. Around midmorning, they were disconcerted to find the train still idling on the tracks in Coffeyville. Their plan derailed, so to speak, the men set off separately, agreeing to meet again in Van Buren.

As posses crisscrossed the region looking for traces of the robbers, lawmen rounded up the likely suspects. On September 11, U.S. Deputy Marshal Ed Jackson arrested Coffeyville gambling house regulars Wallace Curry and George Rauhut and two associates after an inebriated Curry bragged in a local saloon he and Rauhut were the Mound Valley bandits. Curry’s drunken jest backfired; the pair spent three months behind bars before being cleared of all charges. Another lawman on the robbers’ trail was Wells Fargo Detective Fred Dodge, who’d made a reputation a dozen years earlier in Tombstone, Arizona Territory. Dodge combed Coffeyville for clues in the week after the robbery. After two days, he recorded in his journal, he “got a starter on a man named Bill Chadborn [sic], who was an outlaw and wanted for many crimes.” Clues to Chadburn’s partners were scarcer, Dodge observed, “[as] Bill usually played a lone hand.” Dodge shared his findings with Labette County Sheriff William Cook who, recalled Dodge, “put the machinery to work to arrest him. Bill was a hard one to catch, and we expected a long siege.”

The siege lasted just three weeks. Unable to find his cohorts in Van Buren, Chadburn gambled away what little cash he had, pawned a gold watch from the robbery for $5 traveling money and turned back for Kansas. He pawned two more watches along the way and arrived nearly broke. On September 26, Chautauqua County Sheriff Sam Hartzell, who’d been looking for Chadburn since his rampage in Sedan, received word he’d been spotted. Hartzell and Undersheriff John W. Taylor set out at once for Elgin, on the state line 10 miles southwest of town. On arrival, they learned Chadburn had moved on, last seen headed west. The sheriff telegraphed ahead to Cedar Vale, but Chadburn had already robbed a poker game there and ridden off, reportedly headed for Dexter, some 13 miles farther northwest. Hartzell wired authorities in Dexter, and by the time he and Taylor rode in, Constable Joe Church had spotted Chadburn and arrested him without incident.

Hartzell and Taylor delivered Chadburn to the jail at Sedan. Possibly still smarting over the poker game robbery, the Cedar Vale Commercial reported the robber had been “taken to Sedan, where he is now being held to wait justice, if there is such a thing left in the courts.” On October 1 Taylor took Chadburn to the Labette County jail at Oswego, to be held pending trial.

Another Chadburn would soon join him behind bars. Will’s younger brother, Fred, a Missouri-Pacific brakeman, had made a chance remark in a restaurant about having run over the body of a man killed in an earlier train wreck. The remark led eavesdroppers to believe he was referring to the murdered messenger, Chapman, and to conclude he had firsthand knowledge of the murder. Though Taylor was skeptical, he dutifully served a warrant obtained by Cook. The Coffeyville Journal criticized Taylor for the arrest of the seemingly law-abiding Chadburn brother, labeling the undersheriff a “tin horn detective.” The Sedan Times-Journal defended its local officer, insisting Taylor had “done all he could to have Fred released and told the authorities from the start that the boy was innocent and that it was an outrage to put him in jail.”

John D. McBrian, the Chadburn boys’ attorney, told The Coffeyville Journal, “The railroad people have about concluded that they have not got the right parties.” McBrian told the paper Fred had been at their sister’s home in Coffeyville the morning of the robbery, while Will had been in Indian Territory. McBrian was half right; before Fred even appeared at a preliminary hearing, authorities dropped all charges against him for lack of evidence.

Wells Fargo detective Dodge and Sheriff Cook, meanwhile, worked up enough evidence to convince Will Chadburn his only chance to avoid the noose was to confess and to name his cohorts. The lawmen brought the Frisco engineer and fireman along with two passengers to the Oswego jail. All four identified Chadburn as the sack-toting robber. Dodge and Cook then met with McBrian and Chadburn’s mother, Malissa, and persuaded them, “Our terms on the trade for Chadborn’s [sic] confession was a good trade—10 years and a day.” Malissa Chadburn pleaded with her son to accept, and on November 8 he confessed. Fingering Hydrick and Shepherd, he insisted he hadn’t known about Chapman’s killing until after they’d fled the robbery scene. He told officers where to find the buried pocketbooks they’d collected from passengers, along with the Winchester he claimed Shepherd used to shoot Chapman.

At Chadburn’s arraignment on December 12 he pleaded guilty to second-degree armed robbery. He received his “good trade” sentence from Judge Jeremiah D. McCue “with a degree of nonchalance and carelessness,” the Oswego Independent noted, “that bespoke the hardened and desperate criminal.” Indeed, the brazen outlaw had appeared in court wearing the coat and vest he’d taken from the protesting Frisco passenger.

With Chadburn bound for hard labor at the state penitentiary at Lansing, it only remained for lawmen to bring in his partners, Hydrick and Shepherd. Wells Fargo didn’t announce their names publicly but notified all relevant law enforcement agencies, including the sheriff at Pine Bluff, Ark., who was still after the pair. When Dodge learned from Pine Bluff Deputy Sheriff W.A. Clay that Hydrick and Shepherd had been arrested and convicted, under aliases, for burglarizing a store in Jackson, Miss., he obtained extradition papers from Topeka and hopped a southbound train. Four days after Christmas the Wells Fargo detective headed back to Oswego with the fugitives.

The Coffeyville Journal noted the arrest and suggested Hydrick be tried in Arkansas for the murder of the Pine Bluff livery stable owner. “If convicted there, he will be hung,” the paper coldly rationalized, “while in Kansas he will go to the penitentiary for life.” Hydrick made a full confession on Jan. 3, 1894. On January 7, Shepherd confessed not only to the robbery but also to shooting messenger Chapman, insisting it was accidental. On February 5, Hydrick and Shepherd heard the sentence of the court: Both were to be “confined in the state prison at hard labor for one year and then to be hung by the neck until dead at such time as the governor of Kansas might direct.”

No governor ever issued such a direction. Shepherd served fewer than three years, dying of tuberculosis at Lansing on May 26, 1897. Chadburn went free two years short of his sentence and continued his unreconstructed life of crime. Hydrick made unsuccessful bids for a pardon in 1898 and 1901. On the latter occasion, Governor William Eugene Stanley replied firmly he saw “no reason why Hydrick should not remain in the penitentiary.”

Hydrick was still at Lansing in July 1905, when a citizens’ posse in Hewins, Kansas, shot down his onetime cohort Chadburn. If he couldn’t gain his freedom, perhaps it contented Hydrick to know he’d outlived his fellow Mound Valley robbers. Besides, he was the lone inmate who could boast he’d once robbed a train with Billy the Kid.

Southern California author and former police officer J.R. Sanders is a frequent contributor to Wild West.

For further reading see Sanders’ Some Gave All: Forgotten Old West Lawmen Who Died With Their Boots On, as well as Under Cover for Wells Fargo: The Unvarnished Recollections of Fred Dodge, edited by Carolyn Lake.