IN 1943, SOMEWHERE NEAR THE TOWN OF ORFORD ON THE SOUTHEAST COAST OF ENGLAND, British major general Percy Hobart stood on a neatly manicured lawn with a croquet mallet in hand. He was about to wrap up a friendly game with British industrialist Miles Thomas, who was advising the government on matters related to tank production for World War II.

Hobart—“Hobo” to his friends at home and in the military—had played croquet with what Thomas would later call “saturnine fierceness,” even though he wasn’t really that much for sports and games. When he’d headed an armored division in Egypt a few years earlier, he’d been irked by his subordinates’ devotion to their late-afternoon polo matches, which typically left them too tired to come back and do more work in the evening, which was precisely what he expected of them. Hobart, they should have known, was all about the work.

A slim 58-year-old with a wispy mustache, Hobart had a piercing gaze and characteristic glower—both of which were magnified by his horn-rimmed eyeglasses. Out of uniform, he might easily have been mistaken for a dyspeptic colonial bureaucrat or cranky prep school Latin teacher. In fact, Hobart was a pioneer in the use of tanks in warfare. Many years earlier, he had envisioned a time when armored machines equipped with ingenious gadgetry would race in perpetual motion across a continually shifting battlefield, rendering traditional tactics and strategies obsolete.

Hobart’s radical views, paired with his haughty, sometimes abrasive manner, had so irritated his superiors in the army that he’d been removed from command of an armored division at the start of World War II and forced into early retirement. At his nadir, in early 1940, the iconoclastic general had been reduced to putting on an armband and serving as a lance corporal in the Home Guard—Britain’s armed civilian militia—of his small village. But just a few months later, British prime minister Winston Churchill—an equally unconventional thinker—abruptly plucked him from the military establishment’s scrap heap. In early 1943, he was given a crucial assignment: devising the technology that would allow the Allies to overcome the Atlantic Wall—the intimidating array of minefields, pillboxes, buried antitank obstacles, and other lethal impediments that the Germans had installed along the Normandy coast to thwart any invading force. This was a daunting, high-stakes mission—one that demanded a creative thinker who saw no idea as too far-fetched. Hobart was just such a man.

As Thomas and Hobart walked off the croquet lawn, Hobart posed a question to his guest: What about a rocket-propelled tank that could simply fly over the traps the Germans had laid? “His idea,” Thomas would recall many years later, “was that if you had a rocket pointing downwards at each corner of a tank or transport vehicle and touched them off simultaneously, the vehicle would jump, and if the rockets were mounted on swivels, it could be conveniently steered.”

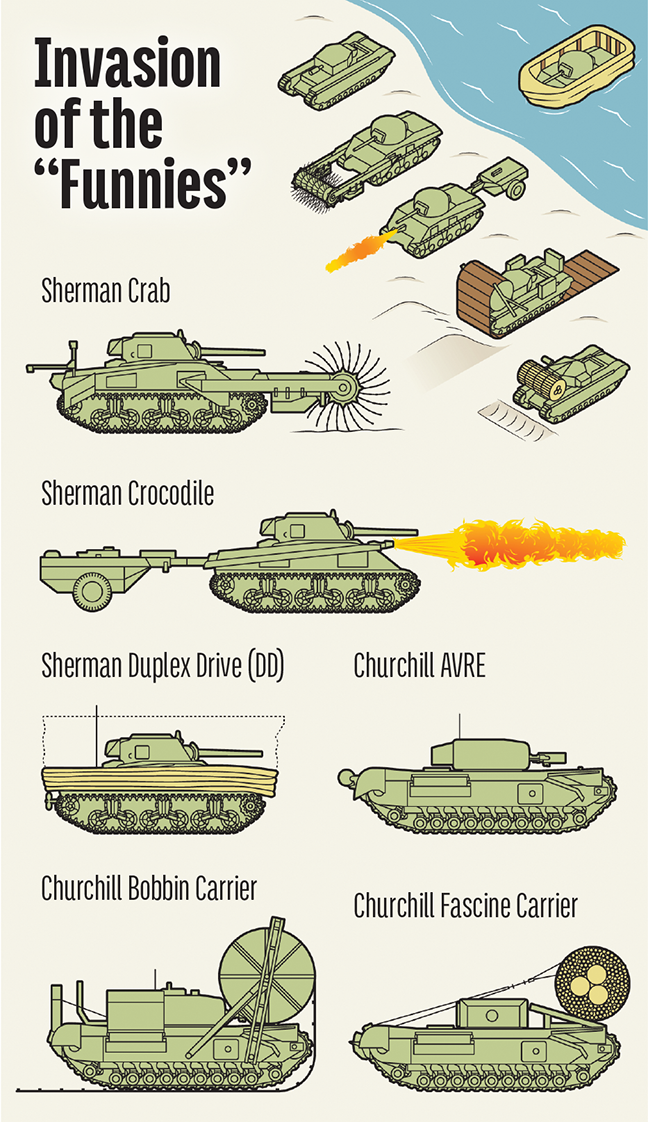

The rocket-powered tank, which never came to fruition, might well have come right out of a science-fiction novel. But it really wasn’t much more outlandish than the modified Churchill and Sherman tanks that Hobart and his 79th Armoured Division actually developed for use in World War II—from tanks that swam or laid down rolls of carpet as temporary roads to others that shot flames or flashed lights powerful enough to blind the enemy. The strange vehicles would become known as Hobart’s “Funnies,” though in truth they were fearsome war machines. Only a buck-the-brass maverick like Hobart could have gotten them from the drawing board to the battlefield. He hated being told that something couldn’t be done; the whole point, he thought, was to figure out how it could be done. Part inventor, part zealot, and part martinet, he would become one of D-Day’s unsung heroes.

IN THE MONTHS LEADING UP TO D-DAY, HOBART RACED BACK AND FORTH from meetings with industrial engineers and designers to the top-secret sites where his men were testing strange armored vehicles with names like the Crab and the Crocodile. Covering up to a thousand miles a week, he typically rode in a staff car with guards on motorcycles all around him. If he needed to be somewhere in a hurry, he and his top aides flew in a small plane piloted by an elderly Frenchman with whom Hobart would chat nonstop.

Having arrived at his destination, Hobart could inspire trepidation in the ranks of those who worked for him. He was known to berate officers, and he pushed his troops hard in tests and drills that were sometimes as terrifying as combat itself. Once he watched an amphibious duplex drive (DD) tank—also jokingly known as a Donald Duck—roll out of a landing craft at sea and sink during a simulated landing, nearly drowning its crew. Hobart’s reaction was to remind the colonel in charge of the exercise that he expected each driver to complete a half-dozen successful launches, under both day and night conditions, before the Normandy invasion. The colonel said he wasn’t sure he would be able to do that. “Oh, of course you will,” Hobart told him. In all, in the three months before D-Day, Hobart’s men managed to complete some 30,000 training launches.

Hobart was just as forceful with British industrialists and others in the private sector, pushing them to produce ever more ingenious and elaborate devices. He came up with some of the ideas himself; others were inventions or innovations he tailored for military use. In this process he could be especially brusque and impatient, which often bred resentment, but that didn’t matter. As Churchill once reminded Field Marshal Sir John Dill, who’d been reluctant to promote Hobart, “We are now at war, fighting for our lives, and we cannot afford to confine Army appointments to persons who have excited no hostile comments in their career.”

THE TANK COMMANDER WHO CREATED ALL THIS CONSTERNATION had been born in India in 1885. Instead of following his father and brother, Charles, into the colonial civil service, Percy Cleghorn Stanley Hobart opted for a military career. After graduating from the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich in 1904, he received a commission in the Royal Engineers. During World War I he served in France, where he was awarded the Military Cross, and in the Middle East, where he survived capture by the Turks and was awarded a Distinguished Service Order.

It wasn’t until after World War I that Hobart first laid eyes on one of its revolutionary innovations: the tank, a formidable new mechanical weapon that combined an internal combustion engine, continuous track, and armor plate. The idea instantly resonated with him. In the Mesopotamian campaign, Hobart had seen how horse cavalry had been supplanted by armored automobiles, which could move rapidly and withstand machine-gun fire.

After fighting on the border of Afghanistan in 1921, Hobart took a position as an instructor at the Staff College in Quetta (in present-day Pakistan). He also officially transferred from the Royal Engineers to the British Army’s then-new Royal Tank Corps, where he befriended officers who’d had experience with tanks during the war and set about learning all he could.

Tanks, Hobart became convinced, would radically alter the nature of warfare. He foresaw a future in which mechanized armor would race across the landscape, keeping pace with airplanes overhead, with infantry following behind to occupy the territory the tanks had cleared. And he envisioned a diverse array of tanks—from fast, light tanks that would be used for reconnaissance to heavier tanks equipped with artillery guns to tanks that would serve as minelayers and minesweepers. He even imagined a tank with an armored headquarters inside that could stay continually on the move. Hobart’s ideas were in sync with those of Basil Liddell Hart, a former officer in the British army who, inspired by the hit-and-run tactics of medieval Mongol cavalry, had become an early proponent of mechanized tank warfare.

Hobart’s ideas about tanks weren’t the only way in which he broke with military convention. He scandalously dared to woo Dorothea Field while she was still married to another officer and to marry her after her divorce in 1928.

By 1934 Hobart was commanding a tank brigade and increasingly pushing his view, in person and in published papers, that the British Army should make a well-equipped armored force the centerpiece of its military strategy. But Hobart’s higher-ups in the War Office, weighted down by tradition and organizational inertia, didn’t share that view. Hobart had watched with alarm as Adolf Hitler’s Nazis began rearming Germany in the mid-1930s. But the brass above him still clung to the belief that the Allies could counter the Germans as they had in World War I, with tanks and aircraft protecting the infantry rather than leading the way into battle.

Making matters worse, the military leader who most enthusiastically embraced Hobart’s views in this regard turned out to be Heinz Guderian, the general Hitler would soon tap to head the Wehrmacht’s tank battalion. Once, the German general brushed aside a skeptic by saying, “I put my faith in Hobart, the new man.”

By 1936 Hobart had grown so desperate to be heard in his own country that he went to see Churchill, who at the time was out of political office, in an effort to enlist him in his crusade to build a modern tank force and make it a key part of Britain’s military strategy. But Churchill—who, as First Lord of the Admiralty, had played a role in Great Britain’s development of tanks during World War I—wasn’t then in a position to help.

In September 1938 Hobart was sent to Egypt to create what eventually became the 7th Armoured Division, but he lasted just 14 months in the post. He repeatedly clashed with his superior officer, Lieutenant General Henry Maitland “Jumbo” Wilson, who saw him as a loose cannon. Wilson dismissed what he called Hobart’s “pernicious” belief that tank units could win an engagement without other troops or weapons. In November 1939, in a letter recommending that Hobart be sacked, Wilson wrote that he had no confidence in Hobart’s ability to command an armored division. Wilson conceded that Hobart was an excellent trainer but argued that “his tactical ideas are based upon the invincibility and invulnerability of the tank, to the exclusion of the employment of other arms in correct proportion.”

Hobart protested, but Wilson won out. In December 1939, scarcely three months into the war, Hobart was relieved, sent home to England, and relegated to reserve status. Even as the division he had trained used his tactics to battle the Germans—its men would become famous as the “Desert Rats”—Hobart’s career seemed to be over. He could only watch in frustration in 1940 as the German army embraced his concept of mobile force to overwhelm and conquer France with lightning speed.

AS HE READ AN ARTICLE IN THE LONDON SUNDAY PICTORIAL JUST WEEKS AFTER GERMANY had pulverized the French defenses, Winston Churchill, now the prime minister of Britain, was anything but amused. The headline alone—“We Have Wasted Brains”—was unsettling enough. The author, Liddell Hart, Britain’s most respected military theorist, argued that Britain’s stodgy military establishment was ignoring some of the country’s brightest thinkers. One such genius, Hart wrote, was Percy Hobart.

Churchill remembered Hobart coming to see him in 1936 and wondered what had happened to him. He soon discovered that Hobart was living in the Gloucestershire village of Chipping Campden, where he bided his time as a lowly lance corporal in the Home Guard while waiting to see whether King George VI would consider his appeal of his forced retirement, which he saw as an insult to his honor and reputation as a soldier.

Unlike those who’d pushed Hobart out of the military, Churchill was unfazed by Hobart’s obsession with mechanized armored warfare. The prime minister loved technological advances and gadgets—back in 1931 he’d written a magazine article in which he imagined such things as nuclear power plants and mobile phones. And when it came to warfare, Churchill believed that technological ingenuity could even the odds against an enemy with superior numbers or firepower. Churchill, who doubled as Britain’s defense minister, pushed the country’s scientists and engineers to come up with new inventions to win what he called the “wizard war.”

Churchill sent one of his officers, General Sir Frederick Pile, to Chipping Campden to talk Hobart into coming out of his forced retirement as a tank expert. Hobart initially resisted, telling Pile that he wouldn’t return until his honor was fully restored, but eventually relented. Hobart went to see Churchill in October 1940 at Chequers, the Gothic mansion in Buckinghamshire that served as the prime minister’s country estate. The two men went for a walk, and then Churchill invited Hobart into his library. When Churchill asked Hobart what he thought it would take to win a truly modern war, Hobart responded that it would require 10 armored divisions.

“How many tanks?” Churchill then asked. Hobart responded that 10,000 tanks would be needed. Churchill nodded. That was precisely the sort of bold thinking the prime minister appreciated.

But Field Marshal Sir John Dill, the chief of the Imperial General Staff, didn’t want Hobart back in the army. According to Churchill biographer Martin Gilbert, Dill told the prime minister that Hobart was “impatient, quick tempered, hot headed, intolerant and inclined to see things as he wished them instead of as they were.” Churchill, in turn, reminded Dill that the war wasn’t going well and that the Germans had proven that Hobart was right about the value of tanks. When another Hobart critic, General Sir Alan Brooke, complained that Hobart was too volatile, Churchill replied, “You cannot expect to have the genius type with the conventional copy-book style.”

In February 1942, on Churchill’s orders, Hobart was given command of the newly formed 11th Armoured Division. But then, after an emergency appendectomy sidelined him for several months, Hobart was reassigned to another new unit, the 79th Armoured Division, and began training exercises to suit his unconventional approach to war.

Soon Hobart would be entrusted with an even bigger and more critical assignment. In March 1943 he was called to the War Office to meet with Brooke, who had replaced Dill as chief of the Imperial General Staff. Hobart may well have gone in expecting another demotion; instead, Brooke told him that he was being put in charge of a highly secret operation, one of the utmost importance. His mission: to organize and develop doctrine and tactics for a fleet of specialized armored vehicles and devices that would be deployed in the invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe. As Brooke outlined the job—developing amphibious, minesweeping, obstacle-clearing, and night-fighting tanks for the invasion—he emphasized that they had little time to get the job done. The always blunt Hobart, who habitually distrusted his superiors, asked whether he would be just a trainer and researcher or go overseas and command the tanks. Brooke smiled at Hobart’s insolence and assured him that once he built and tested the machines and related technology, it would be natural for him to direct their use in battle as well.

That, of course, is exactly what Hobart wanted to hear.

HOBART’S NEW ASSIGNMENT WAS ENTIRELY CHURCHILL’S DOING. The Allies’ disastrous attempt to raid the German-occupied French port of Dieppe in 1942 had shown just how strong the Nazis’ coastal defenses were, and Churchill feared and respected German field marshal Erwin Rommel, who commanded them. As military historian Patrick Delaforce would later note, Churchill admitted that he needed an “antidote” to Rommel’s cleverness.

Hobart, with his mad-scientist manner, was just the man to develop it. He set up his headquarters at a training field west of Orford, whose residents were quietly relocated so that Hobo’s men could test new technology unobserved. He arranged to have several other training grounds at his disposal as well, including a live-fire area for tanks at Linney Head in South Wales, and a secrecy-shrouded lake in Norfolk, where amphibious armored vehicles could be tested before they were deployed in the unforgiving waters of the English Channel.

Once settled, Hobart tackled the job with precision and persistence. His men built mock-ups of German minefields, walls, pillboxes, and beach obstacles so they could test new inventions and figure out new technologies to overcome the enemy’s elaborate defenses. Hobart also systematically broke down the steps for a successful invasion. The first step was to land tanks on the beach so they could lead. Next the tanks should clear any immediate obstacles and barriers, allowing the invading force behind them to advance. Then the tanks would need to breach enemy fortifications and pave the way—sometimes literally—for Allied forces to cross ditches and other gaps in the terrain. Finally, the tanks would have to attack bunkers and other strongpoints of the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall.

With his own seemingly boundless energy, Hobart pushed his men to the edge of exhaustion. One evening, according to Hobart biographer Kenneth Macksey, a subordinate told him about an anti-mine device they were testing. Hobo surprised the officer by showing up early the next morning in the training field and asking to see it work. Told that it wasn’t yet ready, Hobart pointedly asked, “What have you been doing all night?”

Hobart continually came up with ideas for the engineers on his staff to tackle, but his real genius was in identifying others’ potentially useful inventions and improving them, often fixing what had been fatal flaws. A case in point: the duplex drive swimming tank, devised by Hungarian-born engineer Nicholas Straussler, who had resettled in England and in the late 1920s and early 1930s headed a company called Folding Boats and Structures Ltd. Because the floats needed to keep a tank from sinking had to be nearly as big as the tank itself, Straussler had devised a watertight canvas screen, supported by metal hoops and containing rubber tubes filled with compressed air, that was attached to the top of the tank. When the tank emerged from the water, the screen could be folded down so that it didn’t get in the way of the tank as it went into battle. When Straussler’s invention had originally been tested in June 1941, two years before Hobart began his research, officials of the War Office didn’t think it was seaworthy. But when Hobart first saw the DD swimming tank, he said he wished that he had thought of it himself.

Hobart’s growing fleet of modified tanks was nicknamed “the Zoo” because many of them were named after animals. The Crab, for example, was a Sherman tank outfitted with revolving chain flails, turning it into a minesweeper that could clear a path a mile and a half long and 10 feet wide in an hour. It became so efficient and dependable that when King George VI came to Orford to inspect Hobart’s division, Hobart impressed the monarch by sending a Crab out to clear a field full of live mines.

An even more fearsome member of the menagerie, the Crocodile, was a modified Churchill Mk VII tank equipped with a device, developed by oil-industry engineers, that ignited a mixture of diesel oil and tar and belched out a 30-foot-wide flame more than 100 yards. On seeing a demonstration of the experimental device, Hobart became fascinated with it. In practice, the Crocodile was a cumbersome weapon, since it had to drag a fuel tank behind it on a trailer and consumed the fuel in no time at all. But Hobart, realizing that even its appearance had the potential to terrify and demoralize enemy defenders, developed tactics in which a thrust by the Crocodile would be the prelude to a quick infantry assault.

Another fright-inducing machine was the Canal Defence Light, a Grant or Lee medium tank with a searchlight powerful enough to blind enemy soldiers.

Other machines in Hobart’s zoo were designed to circumvent various enemy obstacles. The ARK (Armored Ramp Carrier) was a tank whose turret had been replaced with folding front and rear ramps. The ramps, when extended, transformed the tank into a bridge. The ARK could drive up the edge of a wall or gully, extend its ramps, and other tanks would drive over it. Yet another modified tank, the AVRE (Armored Vehicle Royal Engineers), carried a box-girder bridge that could support 40 tons.

No matter how many exotic gadgets he grafted onto tanks, Hobart never seemed quite satisfied. He constantly badgered industry executives and his superiors in the War Office to come up with even more innovative technology. “There seems to be in some quarters a frigid attitude as regards mechanical matters,” he wrote to officials in London. “I believe this is due largely to inadequate coordination of the activities of designers, producers, and users and insufficient drive behind design and production.”

And when Hobart and his men found flaws, they either fixed them straightaway or devised workarounds. When they discovered that the Crab minesweepers sometimes got bogged down while flailing on soft ground, for example, Hobart’s men built a plow that, when attached to the front of the AVRE, could dig 18 inches into the soil and push mines to either side.

ONE MORNING IN LATE JANUARY 1944, BROOKE VISITED HOBART’S TRAINING FACILITY AT ORFORD, bringing with him a special guest: General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme commander of Allied forces in Europe. Hobart showed the generals his models and plans for how the equipment would be used in an assault. He then put on a demonstration, which by one account was marred when an AVRE fell off an assault bridge while trying to climb a wall and flipped over. Eisenhower stepped up anxiously to see if anyone had been injured. Hobart stopped him. “Don’t worry,” he said, seemingly unconcerned. “They do it every day.”

Two days later Eisenhower sent Hobart a note saying that he had been so impressed by the machines that he wanted his officers to take a look as well. But Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, who would command the U.S. First Army in the invasion, wasn’t quite as enthusiastic. He spurned Britain’s offer to share its exotic equipment, except for the DD swimming tanks.

As D-Day drew closer, the British learned of another trap the Germans had laid for them. An Allied reconnaissance team had slipped onto Normandy’s beaches and collected samples of soft blue clay that the Germans had embedded in long strips on the beach, in hopes that tank treads would get stuck in it. Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, who commanded the Allied land forces for the invasion, told Hobart to come up with a way to cross the soft patches. He sent his men out to scour England for samples of similar blue clay and on their return put his engineers to work. They eventually came up with a solution: the Bobbin, a tank that could lay down a 110-yard-roll of 10-foot-wide fiber matting, creating a temporary road surface directly over the soft clay.

Meanwhile, Hobart insisted that training continue at a feverish pace. Just practicing with the DD tanks in the water was so dangerous that on one day in April 1944, six tanks were lost and six men drowned. But that tragedy led to the discovery of a weakness in the design of the floating screen, which was immediately fixed.

As D-Day approached, Hobart’s crews checked their tanks, making sure they were waterproof, and went over the details of their roles in the operation again and again. Montgomery’s plan called for the Allies’ armored vehicles to penetrate German defenses early in the invasion. It would soon be time to see if Hobart’s Funnies worked in battle too.

The night before the invasion, Eisenhower was wrestling with the decision of whether to brave the bad weather. (British vice admiral Bertram Ramsay, one of the invasion planners, had expressed grave concern about the forecast.) Hobart, stationed at Montgomery’s tactical headquarters at St. Paul’s School in London, couldn’t sleep; he was worrying about his exotic tanks and how they would fare in a dangerous amphibious landing.

Montgomery, who was married to Hobart’s sister, Betty, had his own doubts about the modified tanks. He thought they were highly vulnerable to the antitank guns the Germans had placed in fortified houses and pillboxes all along the Normandy coastline. Ultimately, he had ordered some of Hobart’s machines—including the Canal Defence Lights with their blinding lights and the flame-throwing Crocodiles—to be held back from the initial beach assaults.

Shortly after 6 a.m. on June 6, Hobart’s tanks hit the beachheads. For all their experimental imperfections, they turned out to be highly effective. Just as Hobart had envisioned, the very sight of the swimming tanks emerging from the surf was a shock to the German defenders. “I still remember very vividly some of the machine-gunners standing up in their posts looking at us with their mouths wide open,” Sergeant Leo Gariepy of the 3rd Canadian Division, who was in the first tank to crawl up onto Juno beach at Normandy, later recalled. “To see tanks coming out of the water shook them rigid.”

Meanwhile, other machines in Hobart’s zoo cleared mines and overcame the Germans’ elaborate layers of defenses. On Gold Beach, for example, the carpet laid by the Bobbins enabled the British to avoid getting stuck in the Germans’ blue clay trap. By the time Hobart himself finally crossed the Channel and landed, on June 8, his unorthodox tanks—farmed out to support all the British and Canadian units fighting in Northern Europe and some in the U.S. Army as well—were already engaged in the drive to push the Germans inland. As Montgomery would later note, they played an increasingly important role as the offensive continued and were, he said, “invaluable” against fixed German defenses.

Hobart’s Funnies would roll into Germany in 1945, helping to end the war. The following March, Hobart retired from the military, this time by choice. For a while he worked as an adviser to Sir Miles Thomas, the same industrialist whom he’d tried to convince, over a croquet game, to build a jet-powered flying tank.

After the war, Eisenhower credited Hobart’s “novel mechanical contrivances,” as he called them, with helping to keep Allied casualties relatively low. In addition to the amphibious tanks, which Eisenhower noted were “conspicuously effective,” he cited the value of the British bridge-carrying AVRE and the Crabs, which, he said, “did excellent work in clearing paths through the minefields at the beach exits.”

Otherwise, though, Hobart didn’t get much personal acclaim. The BBC approached him to do an interview for a 1956 television documentary on D-Day, but by then he was too ill from cancer to participate. After his death in February 1957, a brief obituary in the Illustrated London News only noted tersely that he was “one of Britain’s leading tank experts.” It wasn’t until a decade after his death that military historian Kenneth Macksey’s biography of Hobart brought his amazing contributions to the public. In the many years since, Hobart has gradually come to be regarded as one of D-Day’s true masterminds—a maverick whose remarkable ingenuity and force of personality enabled the Allied triumph. As Liddell Hart noted on Hobart’s death, “He was one of the few soldiers I have known who could be rightly termed a military genius.” MHQ

Patrick J. Kiger is an award-winning journalist who has written for GQ, the Los Angeles Times Magazine, Mother Jones, Urban Land, and other publications.

[hr]

This article appears in the Summer 2019 issue (Vol. 31, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: D-Day’s Unsung Hero

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!