By the time the XPB2M-1R was delivered to the Navy, the tide of war had turned in favor of the Allies on both ocean fronts.

Glenn L. Martin was said to have been obsessed with big flying boats. His obsession would see its ultimate expression in the Martin Mars, among the largest aircraft ever built. Remarkably, two of these water-based behemoths, once destined for the scrap heap, remain in service today as firefighters, more than six decades after they first flew.

Although Martin’s role as a U.S. Navy contractor dated to 1916, his interest in flying boats actually came years later, when the Naval Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) contracted with his firm in mid-1929 to manufacture 25 PM-1s. The PM-1 was a twin-engine biplane flying boat built according to detailed plans and specifications issued by the government-owned Naval Aircraft Factory (NAF). Martin’s order was part of a larger effort by the Navy during the late 1920s to replace its obsolescent fleet of World War I–era flying boats with newer designs. Similar contracts were awarded to other aircraft manufacturers. Five more PM-1s were added to Martin’s contract in 1930, and in 1931 the Navy ordered 28 improved PM-2s.

While construction of the PM series was ongoing, BuAer assigned Martin an even more advanced flying boat project, a three-engine monoplane designated the XP2M-1. Interestingly, the design’s basic blueprint had been conceived by Consolidated Aircraft and tested in early 1929 as the XPY-1. This was a byproduct of standard naval procurement methods of the 1920s, whereby rights to a particular aircraft design became the property of the Navy and could ultimately be produced by any of its airframe contractors, including NAF.

In 1931, once the XP2M-1 had been evaluated, BuAer directed Martin to reconfigure the design for two engines as the XP2M-2. This was ordered into limited production in 1931-32 as the P3M, with three delivered as the P3M-1 and six as the P3M-2. The P3Ms operated alongside Consolidated’s analogous P2Y production series, marking the beginning of a heated rivalry between Martin and Consolidated over various flying boat contracts during the 1930s.

Having established itself as a seaplane builder of some repute, Martin received a request in 1931 from Pan American Airways to design a long-range, passenger-carrying flying boat capable of operating on transoceanic routes in the Atlantic. But in 1933, before any final design had been fixed, Pan American changed its requirements to capability for routes in the Pacific. The route, as finally determined, entailed an 8,200-mile flight from San Francisco to Manila, in the Philippines, via Hawaii, Midway, Wake and Guam. It was later extended to include Hong Kong. At a minimum, this required an airplane capable of carrying fuel, passengers and mail over the 2,410-mile segment between California and Hawaii, a highly ambitious undertaking for any aircraft manufacturer of that era.

When it flew in December 1934, the Martin Model 130, dubbed China Clipper by Pan Am, represented state-of-the-art flying boat design. A combination of advanced aerodynamics and four 850-hp Pratt & Whitney R-1830 double-row radial engines enabled it to lift more than twice its empty weight, thereby exceeding the payload ratios of contemporary landplanes such as the Boeing 247 and Douglas DC-2/-3. Two more Model 130s were delivered to Pan Am in 1935-36. In its contest against Boeing’s new Model 314, however, Martin’s efforts to sell the 20-percent-larger Model 156 were unsuccessful, and the sole example was sold to the Soviet Union in 1938.

Starting in 1933, Consolidated’s PBY series dominated the Navy’s flying boat market, as illustrated by the sale of 100 PBY-1s and -2s between 1935 and 1937 (a truly enormous quantity by Depression-era standards). Consolidated also attempted to interest BuAer in its much larger four-engine XPB2Y-1. Martin, after successfully selling large numbers of B-10 bombers to the Army, endeavored to regain a share of the naval flying boat market in 1936 by submitting a competitive proposal for the four-engine Model 160. But BuAer promptly rejected it, citing a preference on the basis of cost for twin-engine patrol boats. Apparently undeterred, Martin submitted a second proposal in early 1937 for the twin-engine Model 162, which the company claimed would be 20 percent faster than the PBY and possess twice its range and payload. When Consolidated disputed Martin’s claims and threatened the Navy with legal action, Martin quickly responded by building a three-eighths scale proof-of-concept demonstrator, the Model 162A “Tadpole Clipper,” which confirmed the company’s performance projections during tests in November 1937. By the end of the year, Martin had received an order to build 21 Model 162s as the PBM-1 Mariner. The company would manufacture a total of 1,366 PBM-1, -3 and -5 aircraft over the next 12 years.

By the late 1930s, Nazi Germany and an expansionist Japanese empire had become tangible threats to world peace. In a worst-case scenario, the isolationist United States could potentially find itself cut off from land bases on both oceans. Even before the XPBM-1 flew, Martin’s engineering staff had started work on the considerably larger four-engine Model 170. When Glenn Martin presented it to BuAer in early 1938, he touted the huge flying boat as a “sky battleship” or “flying dreadnought” able to defend itself and deliver a 10,000-pound bombload (2½ times that of the Boeing YB-17) over long distances from sea bases. The Navy was sufficiently impressed to order one prototype in August 1938 as the XPB2M-1. Due to other factory commitments, Martin was unable to begin building the aircraft until mid-1940, and it was not ready for taxiing tests until early November 1941.

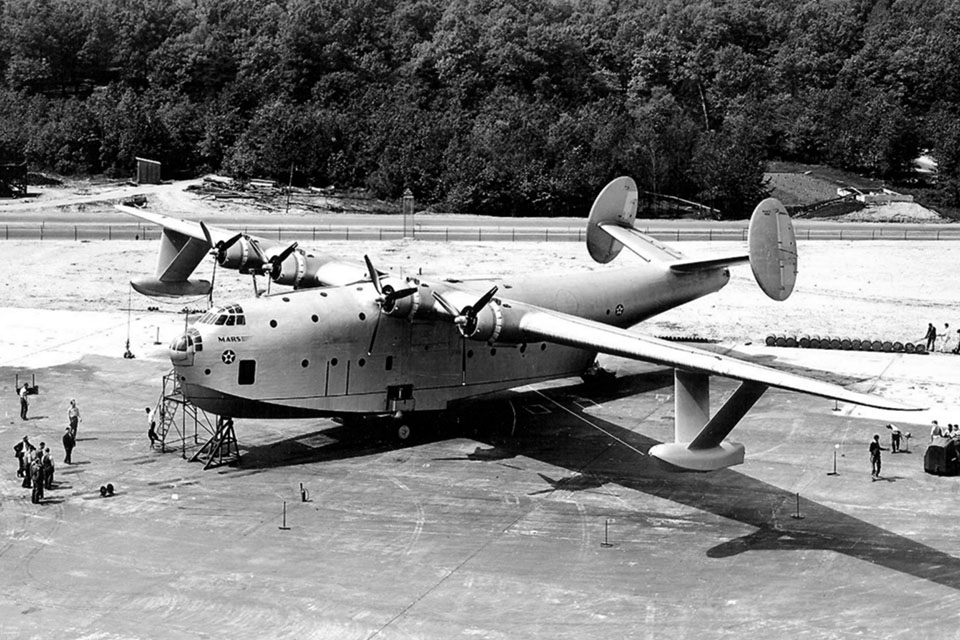

In line with the company practice of choosing names that started with “M,” the big flying boat was dubbed Mars. Sharing the general hull design and twin-fin arrangement of the PBM, the XPB2M-1 was powered by four Wright R-3350-8 engines rated at 2,200 hp each. It boasted a wingspan of 200 feet, a length of 117 feet 3 inches and a loaded weight of 144,000 pounds. Planned armament consisted of five turrets, each mounting one .30-caliber machine gun, and a bomb bay under each wing holding up to five 1,000-pound bombs. At that time it was the largest flying boat and the third largest aircraft of any type in the world (the Tupolev ANT-20bis of 1938 and the Douglas XB-19 of 1941 were fractionally larger).

The program experienced a critical setback during taxi tests when the No. 3 engine threw a propeller blade and caught fire. By the time the XPB2M-1 was towed back to shore and the fire extinguished, the aircraft had suffered serious damage to its starboard wing and No. 3 nacelle, as well as structural damage where the propeller blade had penetrated the fuselage. It took Martin more than six months to complete repairs, and the XPB2M-1 did not make its first flight until July 2, 1942. In the interval, the U.S. had declared war on Japan and Germany and had already fought two important naval battles in the Pacific. This experience caused naval planners to completely discard the notion of the sky battleship in favor of smaller combat aircraft operating from carriers, together with greater numbers of twin-engine flying boats (i.e., PBYs and PBMs) employed for maritime patrols, effectively leaving the big Mars without a combat role.

Around the time the XPB2M-1 first flew, the U.S. was confronted with a serious threat to its Atlantic shipping lanes from marauding German U-boats. Fleets of large flying boat transports—“sky freighters” that would be immune from torpedo attack—were seen as a potential means of moving large quantities of war materiel to Great Britain and other battlefronts. Thus it came as no surprise in early 1943 when BuAer authorized Martin to remove all armament and bombing gear from the Mars prototype and modify it as a transport under the new designation XPB2M-1R. To boost production, industrialist Henry J. Kaiser offered to license-build the Mars by the hundreds in his West Coast shipyards. Glenn Martin expressed no interest in sharing his production rights with another manufacturer, however, and Kaiser moved on to better prospects.

Factory testing of the transport conversion was completed in mid-1943, and the XPB2M-1R was delivered to the Navy for operational evaluation and crew training later the same year. By that time, however, the tide of the war had turned in favor of the Allies on both ocean fronts, and there was no longer a need for large numbers of sky freighters. (This turn of events also resulted in the cancellation of other big flying boat projects, including Howard Hughes’ gargantuan 400,000-pound H-4 Hercules and the proposed 250,000-pound Martin Model 193, a six-engine 25 percent scale-up of the Mars.)

Fortunately, the story of the Mars did not end here. After being assigned to transport squadron VR-2 out of Naval Air Station Alameda, Calif., the XPB2M-1R, now known as Old Lady, proved to be an excellent freight hauler, routinely carrying up to 10 tons of cargo between Hawaii and California. BuAer liked it well enough to order 20 new aircraft, designated JRM-1s, in June 1944. Also known as the Model 170A, the JRM-1 differed from the prototype in that it had a single vertical fin, a hull lengthened by 3 feet, fewer internal bulkheads and new cargo-handling equipment. The installation of 2,500-hp R-3350-24W engines, plus new four-bladed propellers, boosted takeoff weight to 148,500 pounds. The first production JRM-1, christened Hawaii Mars, was delivered in late July 1945, but was destroyed only two weeks later in a landing accident on Chesapeake Bay. Four more JRM-1s were delivered to the Navy before the end of the year. As a result of V-J Day cutbacks, however, the original order was reduced to just six aircraft.

Martin also had aspirations to sell an airliner version of the Mars, the 79-seat Model 170-24A, to be powered by Pratt & Whitney R-4360 engines. But when the postwar market for civilian flying boats failed to materialize, the project was abandoned. The sixth and final Mars built, the JRM-2, was completed in 1946 with the 3,000-hp R-4360-4 power plants originally intended for the Model 170-24A airliner. The JRM-2’s increased power permitted a takeoff weight of 165,000 pounds and added more than 10,000 pounds to its useful load. Its fully reversible propellers on the two inboard engines allowed the aircraft to back up or stop within shorter distances. During the late 1940s, in order to bring them up to the increased payload capability of the JRM-2, the four remaining JRM-1s were modified to allow installation of R-4360 engines and were redesignated JRM-3s.

Destined for Pacific service, all five JRMs were assigned to VR-2 at NAS Alameda. VR-2’s mission during the war had been to provide a fast means of moving critical supplies, spares and personnel over the vast transoceanic distances of the Pacific theater. In addition to its prior experience with the XPB2M-1R, the unit had been operating other types of large flying boats such as the Mariner and the cargo adaptation of the Consolidated PB2Y Coronado, so the big Mars was a logical fit. Once operational, the JRMs were used primarily to transport cargo and personnel on the regular run between Alameda and Pearl Harbor. But during their tenure with VR-2, the big flying boats did occasionally divert from their routine duties to chalk up some impressive records: In 1948 Caroline Mars carried a payload of 68,282 pounds (twice the normal load) from Baltimore to Cleveland; in 1950 the same plane transported 144 Marines from San Diego to Honolulu; and in 1949 Marshall Mars carried a record 301 servicemen plus a crew of seven from San Diego to Alameda.

On May 5, 1950, while Marshall Mars was flying off Diamond Head in Hawaii, one of its engines caught fire and the aircraft was forced to make an emergency landing. Although the crew escaped injury, the big flying boat was entirely consumed by flames. Other than this incident, the operational record of VR-2’s JRMs was nearly flawless, and the remaining four aircraft continued to provide safe, reliable and economical air transportation.

In 1956 the Navy decided to discontinue cargo operations with flying boats, and the final Mars military flight took place on August 22, 1956. Thereafter, the four JRMs were hauled out of the water on beaching gear and consigned to the boneyard at Alameda. After sitting idle for nearly three years, the big aircraft were offered for sale as scrap. Similar to the fate shared by so many other old airplanes that had theoretically outlived their usefulness, it appeared that the next step for the mighty Mars was the chopper, then oblivion—almost.

Enter Dan McIvor, a veteran Canadian corporate pilot. During the 1950s western Canada had been plagued by forest fires that destroyed thousands of acres of timberland, and McIvor was one of small group of pioneers who were developing the concept of using aircraft to fight them. When he learned that the U.S. Navy was selling off four Martin Mars flying boats at scrap metal prices, he figured the big planes would be ideally suited to serve as firefighters. Upon further inquiry, however, he discovered that all four had already been sold to a scrap dealer (who apparently planned to part them out) for a total of $23,650. After making a convincing case to his financial backers—several of Canada’s major lumber corporations—he was able to persuade the scrap dealer to resell the big airplanes for $25,000 each, and ownership of the four JRMs was subsequently transferred to Forest Industries Flying Tankers (FIFT).

In addition to closing the deal on the planes, McIvor had the presence of mind to anticipate the maintenance and logistical difficulties associated with supporting such large aircraft, and almost immediately made arrangements to purchase spare engines, eventually buying 35 at scrap metal prices, as well as many new spare parts for the JRMs that remained in the Navy inventory. With this level of preparation, the Mars flying boats could be kept airworthy on a very long-term—almost indefinite—basis.

Once they were flyable, the four JRMs were moved one at a time to Fairley Aviation of Canada, at Victoria International Airport in Sidney, British Columbia, off Patricia Bay. Initially, two of them underwent an extensive air tanker conversion process, which involved retrofitting newly overhauled R-3350-24WA engines (in place of the R-4360s), removing all unnecessary military equipment and installing 6,000-gallon water tanks in the fuselage along with retractable scoops on the bottom of the hull. The scoops were designed to enable the aircraft to replenish its water tanks while skimming across a lake, allowing a rapid turnaround between water drops. The decision to switch to R-3350 engines, and accept the resultant reduction in payload, was likely due to long-term maintenance considerations. The original plan involved converting two of the planes and holding the other two in reserve—a wise choice as it turned out, because FIFT’s flight operations got off to a very shaky start.

The first aircraft to be converted, Marianas Mars, was ready for service by the spring of 1960, but disaster struck on June 23 when the pilot, misjudging his altitude, cartwheeled the big flying boat into the forest, killing himself and three crew members. McIvor was temporarily grounded at the time due to eyesight problems. Conversion of the second aircraft, Caroline Mars, was completed in early 1962, and with McIvor at the controls it began responding to fire calls that rapidly demonstrated its superior firefighting qualities. Unfortunately, in October of that year, while ashore for maintenance, the plane was wrecked beyond repair by Typhoon Freda.

But these misfortunes did not deter McIvor and his associates. Philippine Mars and Hawaii Mars were ready to enter service in 1963 and 1964, respectively. During the conversion, Philippine Mars received water tanks in the main fuselage, where the cargo holds were located, with water drop ports located on either side of the fuselage. Hawaii Mars was given a more conventional treatment in which the water tanks were installed near the bottom of the hull (in place of fuel tanks), with drop ports in the belly. Both aircraft were subsequently rated to operate with a load of 7,200 gallons, together with separate tanks containing 600 gallons of chemical foam concentrate. The separate elements of water and foam concentrate were designed to mix and catalyze as they exited the drop ports.

From their base on Sproat Lake, west of Port Alberni, B.C., FIFT’s two tankers resumed water-bombing operations, which would continue, virtually without mishap, for the next 44 years. Both big flying boats, adorned with vivid red-and-white paint schemes, became a common sight over the forests of western Canada. It is said that whenever the Mars tankers arrived in response to a call, no fire ever got out of control.

In its water-bomber role, the potency of the Mars is unsurpassed by any aircraft. Rated under firefighting guidelines as a Type I Tanker, the Mars can take off with 2.4 times the load carried by other converted aircraft such as the Lockheed C-130 Hercules and P-3C Orion and Douglas DC-7 transport, and possesses the added capability of refilling its tanks on the fly. The most comparable flying boat equipped with water scoops, the Canadair CL-415, has a capacity of only 1,600 gallons. When a Mars makes a water drop, typically from 150 feet, the water and foam mixture can cover up to four acres with a 4-inch carpet of foam. A firefighting Mars normally carries a crew of four: a captain, first officer (co-pilot) and two flight engineers. Lightheartedly referring to themselves as “Martians,” the pilots selected to fly them generally possess considerable flying experience (i.e., 10,000-plus hours) and plenty of logbook time as pilot-in-command of flying boats and seaplanes.

On April 13, 2007, FIFT announced plans to sell Philippine Mars and Hawaii Mars to Coulson Aircane Ltd., another British Columbia–based company, for an undisclosed amount. Its Coulson Flying Tankers subsidiary now operates the two mammoth flying boats as firefighters, just as they have been used for the past 47 years. That announcement ended an almost six-month “Save the Mars” fundraising effort by the Glenn L. Martin Museum in Baltimore, Md., to purchase one of the planes. The giant flying boats were closely associated with Baltimore, where they were built and where reminders include the Mars supermarket chain and Mars Estates Elementary School.

According to Coulson’s Web site (martinmars.com), “The Mars are spreading their 200 ft. wingspan to provide firefighting protection on a call out service or contract basis to any company or agency requiring the unique initial attack and sustained action qualities of the Mars.” One can only hope that at some point in the future, once they have fought their last fire, at least one of these magnificent aircraft will be preserved for posterity.

U.S. Navy veteran E.R. Johnson is a pilot, aviation author and major in the Arkansas Wing of the Civil Air Patrol.

The Mighty Mars originally appeared in the January 2009 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today!