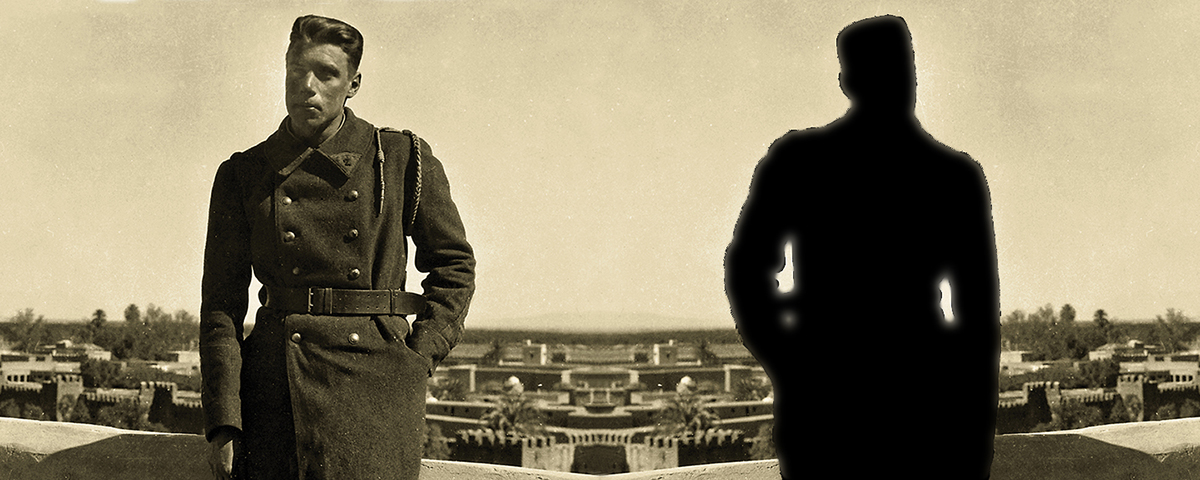

One evening in the spring of 1944, the story goes, a tall, handsome man sat at a table in a bar in Nazi-occupied Lyons, France, listening with increasing irritation to the conversation among his drinking partners. The men, officers of the German Wehrmacht, were complaining about how a uniformed U.S. Marine Corps officer was helping the local Maquis attack German troops and installations. One man explained in lurid detail what he would do to the American if given the chance, and then the entire group began cursing the French resistance, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Allies and the Marine Corps in particular.

The tall man excused himself and discreetly slipped out of the bar. Minutes later he returned wearing a long raincoat. After ordering another round of drinks for the Germans, he suddenly flipped back his coat, beneath which he wore the uniform of a Marine captain and held a drawn .45-caliber pistol. Shocked into silence, the Wehrmacht officers could only comply as the American ordered them to toast first Roosevelt and then the Corps. Grinning widely, the Marine then backed out the doorway and disappeared into the darkness.

Pierre Ortiz had struck again, in typical swashbuckling style.

‘I wanted to live a man’s life’

The man who would eventually become a legendary Marine and member of the clandestine U.S. Office of Strategic Services was born in New York City on July 5, 1913, as Pierre Julien Ortiz. His French-Spanish father, Philippe, and Swiss-born mother, Marie Louise, separated when he was a young man, and Pete, as he was known, lived with his socially connected mother after his father returned to Europe. On graduation from high school Ortiz himself traveled to France, where he enrolled in the University of Grenoble. Though intelligent and multilingual—he spoke English, French and Spanish with equal fluency—Ortiz grew bored with the college curriculum and in 1932 dropped out to enlist for a five-year stint in the French Foreign Legion. His father sought in vain to rescue his son from what he saw as potentially disastrous youthful folly. After induction and initial processing in Marseilles, the young man was sent to Sidi Bel Abbès in French Algeria.

At Sidi, the legion’s basic training center and spiritual home, Ortiz and fellow recruits from across Europe underwent schooling that was intentionally harsh. It had to be, for at the time the legion was bearing the brunt of France’s ongoing colonial unrest in Morocco, Tunisia and Indochina. Despite the intense physical and mental challenges, Ortiz thrived on the training. George Ward Price, a British journalist who met him during that period, wrote of the young legionnaire, “This distinguished-looking young American would have made an officer of whom any army in the world would have been proud.” When Price asked why a young man of means would willingly subject himself to the hardships of service in the legion, Ortiz had a clear answer: “Yes, it’s as hard as anything in the world, I suppose, but I don’t regret going for it. I wanted to live a man’s life. What should I have been doing if I had stayed in Paris? Cocktail parties, nightclubs?”

During his time in the legion Ortiz added Arabic to his list of languages, while proving a natural and highly gifted warrior. He completed parachute training, saw extensive combat in Morocco and rose steadily in rank. Appointed a corporal, he was soon named the youngest sergeant in the legion to that time and ultimately rose to become acting lieutenant in command of an armored car squadron. During his tour Ortiz received numerous awards for valor in combat, including the Croix de guerre with two palms, the Croix de combattant and the Médaille militaire. His superiors also offered him a permanent commission, which Ortiz declined, as he did not wish to give up his American citizenship, as required.

When Ortiz’s enlistment in the legion ended in 1937, he headed to California to rejoin his mother and seek new challenges. Once stateside he worked on a dude ranch, served as a technical adviser on Hollywood war films and, according to family legend, even briefly “ran away with the circus.” He also kept a sharp eye on events in Europe, and following the September 1939 German invasion of Poland and subsequent outbreak of war, he made his way to Canada and signed on as a deckhand aboard a ship bound for France. He survived the vessel’s sinking by a German U-boat, was picked up by a French destroyer and in October re-enlisted in the legion.

After additional training at Sidi, Ortiz and his unit were shipped to France. Following the May 1940 German invasion he received battlefield commissions to second lieutenant and soon first lieutenant. Within weeks the Germans overran his unit, and the severely wounded Ortiz was captured and sent to a series of prisoner of war camps. In October 1941, though only partially recovered, he managed to escape. Eluding his pursuers, he reached his father’s apartment in Paris. Following several weeks of recuperation he made his way through unoccupied France, crossed the border into neutral Spain and in Lisbon boarded a ship headed to the United States.

Ortiz fully intended to return to Europe and fight the Nazis. But as his native country remained neutral, he was initially unsure just how to go about it. When his ship was two days from port in New York, the problem resolved itself.

The date was Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into the war ensured Ortiz could at last serve in his own nation’s armed forces. But joining the U.S. war effort initially proved more difficult than he had imagined.

The first issue was his health. His wound and the rigors of his captivity and escape across Europe had left Ortiz in poor physical condition. To get back into fighting trim, he decided to continue his recuperation at his mother’s home near San Diego.

The second issue—how best to serve his nation—was not such an easy decision. On his return to the United States, military intelligence officials in Washington, D.C., had interrogated Ortiz about what he had witnessed in Europe. During those meetings they had suggested he would make an ideal intelligence officer, and over the following weeks Ortiz had initiated the necessary paperwork toward a commission in Army Air Forces intelligence. When red tape stalled the process, Ortiz considered other options. Perhaps motivated by a meeting he’d had in Sidi with a visiting Marine Corps officer during his initial stint in the legion, Ortiz began to think his martial talents might be better used as a combat Marine than as a staff intelligence officer. In the early summer of 1942 he left California for the East Coast, and in Baltimore on June 22 he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps.

Sent to Parris Island, S.C., for basic training, Ortiz must have been amused by the frightened faces of the new recruits and the posturing of drill instructors. Even more humorous must have been the reaction of his instructors when Ortiz appeared on the drill field wearing the French valor awards to which he was entitled. A July 14 letter from a senior commander at Parris Island to Marine Corps Commandant Lt. Gen. Thomas Holcomb in Washington described the “unique new recruit” and suggested that offering him a commission might be in the best interest of the corps. On completion of basic training Ortiz was duly commissioned a second lieutenant and sent to Camp Lejeune, N.C., as a training officer. He was then ordered to attend the Marine Parachute Training School in New River, N.C. Though Ortiz already had dozens of jumps under his belt, he took the training in stride. “The legion had its way, and the Marine Corps had the right way,” he quipped. “I never minded jumping.”

Sent to Parris Island, S.C., for basic training, Ortiz must have been amused by the frightened faces of the new recruits and the posturing of drill instructors. Even more humorous must have been the reaction of his instructors when Ortiz appeared on the drill field wearing the French valor awards to which he was entitled. A July 14 letter from a senior commander at Parris Island to Marine Corps Commandant Lt. Gen. Thomas Holcomb in Washington described the “unique new recruit” and suggested that offering him a commission might be in the best interest of the corps. On completion of basic training Ortiz was duly commissioned a second lieutenant and sent to Camp Lejeune, N.C., as a training officer. He was then ordered to attend the Marine Parachute Training School in New River, N.C. Though Ortiz already had dozens of jumps under his belt, he took the training in stride. “The legion had its way, and the Marine Corps had the right way,” he quipped. “I never minded jumping.”

‘The legion had its way, and the Marine Corps had the right way’

In November Ortiz’s superiors suggested to Commandant Holcomb the young man’s unique talents and experiences might prove useful in North Africa, where American and British forces had just launched Operation Torch. Ortiz was temporarily assigned to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency, and ordered to report to Marine Corps Lt. Col. William Eddy, a legend in Middle East intelligence gathering then based in Tangier, Morocco. Promoted to captain and bearing the title of assistant naval attaché, Ortiz flew a circuitous route from Washington to London, Gibraltar, Algeria and, finally, Casablanca, Morocco. From there he took a train to Tangier.

During the two-week trek his fluency in French, Arabic and other languages enabled him to gather useful information, as did his social network—from his legion days Ortiz was acquainted with many of the region’s influential military and political leaders, and his conversations with them gave him a unique perspective on French activities and intentions in North Africa. He shared this intelligence on his arrival in Tangier on Jan. 15, 1943.

As a military attaché and OSS operative Ortiz spent time with U.S., Free French and British units in the region, though he did not limit himself to simply observing their activities. He took part in combat operations against German forces on several occasions and in Tunisia was attached to both the U.S. 1st Infantry Division and a French Foreign Legion unit during the brutal February 19–24 Battle of Kasserine Pass. By early March he had been given temporary command of a reconnaissance and sabotage team belonging to Britain’s Special Operations Executive (after which OSS had been modeled) and was operating in Tunisia.

He then attached himself to a British light armored unit, and while undertaking a solo night reconnaissance mission on March 17, he was shot in the right hand during an encounter with a German patrol. Following surgery in an Allied field hospital he was told he likely faced months of hospitalization and convalescence. Not wanting to be sidelined that long, Ortiz sought help from an acquaintance who served as the operations officer at a nearby British airfield.

The man arranged for the wounded Marine to fly to Algiers, where he reported to Colonel Eddy. Though impressed by Ortiz’s capabilities, the senior officer realized his combat activities were conflicting with his diplomatic status as an attaché. Moreover, Ortiz needed to fully recover from his hand wound. Eddy therefore reluctantly ordered the young man’s evacuation back stateside.

Reporting to Headquarters Marine Corps in Washington on April 28, Ortiz wrote an in-depth report for OSS Director William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan. Also suitably impressed, Donovan personally reviewed Ortiz’s military records and then directed subordinates to arrange the young Marine’s transfer to full-time duty with the clandestine agency.

Ortiz didn’t realize it yet, but his superiors were sending him back to France.

As the Allies geared up for Operation Overlord, the planned invasion of Nazi-occupied France, the OSS was tapped to help conduct intelligence gathering and sabotage operations. Its mission necessitated cooperation with the various groups that made up the French resistance, and OSS would—at least initially—operate in conjunction with Britain’s SOE. The two services established joint Jedburgh teams (named after Jedburgh, Scotland, where they trained), typically comprising two officers—one SOE, one OSS—and an enlisted French radio operator. These teams were to be dropped into France just before the invasion to establish contact with local resistance groups and wreak havoc on the Germans.

In May 1943 OSS Director Donovan had Ortiz reassigned to the agency’s Special Operations branch, and by early August, Ortiz was in England. There he joined British army Colonel H.H.A Thackwaite and French radio operator Camille Monnier to form one of the first Jedburgh teams. After additional training the three parachuted into the Rhône-Alpes region of southeastern France on Jan. 6, 1944—six months ahead of the official start of the Jedburgh program—launching Operation Union I.

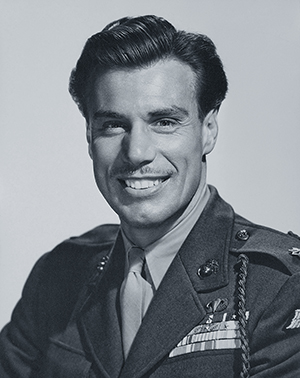

The trio quickly made contact with the local resistance, and over the next five months Ortiz and his companions helped mold the different splinter groups into organized fighting units, set up systems to help the fighters’ families, and arranged airdrops of needed weapons and equipment. When mixing with the general population, the men wore civilian clothes and used cover identities. Given his ability to speak some German and French like a native, Ortiz was especially good at gathering information. Though rather conspicuous at 6 feet 2 inches with movie star looks, he passed himself off as an effete French fashion designer who was in the region because there was no work in Paris and he liked the local winter sports.

But the Jedburghs also took an active role in the fight, attacking the Germans whenever they could. The team members donned their uniforms when carrying out combat operations, and Ortiz, with his many American and French decorations, was especially inspiring to the resistance fighters. He sabotaged rail lines, stole military vehicles from German motor pools, ambushed enemy patrols and, in one particularly audacious operation, walked into a German-run jail pretending to be a Wehrmacht officer and spirited away several captured British airmen.

Ortiz’s antics didn’t go unnoticed by the Germans, of course. They flooded the team’s area of operations with troops, repeatedly forcing the trio to change safe houses. Both the Germans and Vichy French offered increasingly higher rewards for the men’s capture, and it soon became apparent they would have to be withdrawn. Pulled out of France in late May, Thackwaite and Ortiz arrived back in London before D-Day. Their radio operator, Monnier, remained behind in France and, sadly, was killed soon after his companions departed.

Ortiz’s return to London marked the beginning of yet another phase in his World War II career. Following his promotion to major and the award of the Navy Cross for “extraordinary heroism” during Union I, he was assigned to a follow-up operation dubbed, appropriately, Union II. Ortiz, a Free French officer, five enlisted Marines and an Army captain who had also served in the French Foreign Legion would be parachuted into the Col des Saisies, a pass in the rugged mountains of Savoie. The region, in the French Alps abutting the Italian border, was a hotbed of resistance, and the OSS men were to both aid the French fighters and undertake direct combat operations to disrupt the Germans as the Allies advanced inland from Normandy.

While the mission was well planned with a clear goal, things got off to a rocky start. The team’s Aug. 1, 1944, insertion was part of a massive, 75-aircraft daylight drop of supplies over Savoie, and the team parachuted from a B-17 bomber at an altitude of just 400 feet to minimize their time in the air. Unfortunately, one Marine was killed when his parachute failed to open, and another was so severely injured that he ultimately had to be smuggled back to England for treatment. And while Ortiz and the other men did rendezvous with the waiting resistance members and begin training and support operations, they soon realized the Germans were following them with unusual tenacity. On August 16, as Ortiz and companions moved through the village of Centron, they ran smack into a convoy of heavily armed German troops. The team scattered back toward the village and sought to evade capture, but the enemy soldiers quickly cut off all escape routes. Cornered, and unwilling to expose the townspeople to possible reprisals, Ortiz and two of his Marines surrendered; the Germans soon rounded up a fourth team member.

Over the following weeks Ortiz and companions were shuttled from France to Italy to Germany, ultimately landing in Marlag/Milag Nord, a POW camp for Allied naval personnel outside the village of Westertimke, near the North Sea port of Bremen. There they remained until liberated by elements of the British Guards Armored Division on April 29, 1945. After several weeks of debriefings, medical treatment and the award of a second Navy Cross, Ortiz returned to the United States in preparation for redeployment to the Pacific. He and three members of the former Union II team were slated for duty in China, but Japanese Emperor Hirohito’s August 15 acceptance of the Allied surrender terms cancelled those plans.

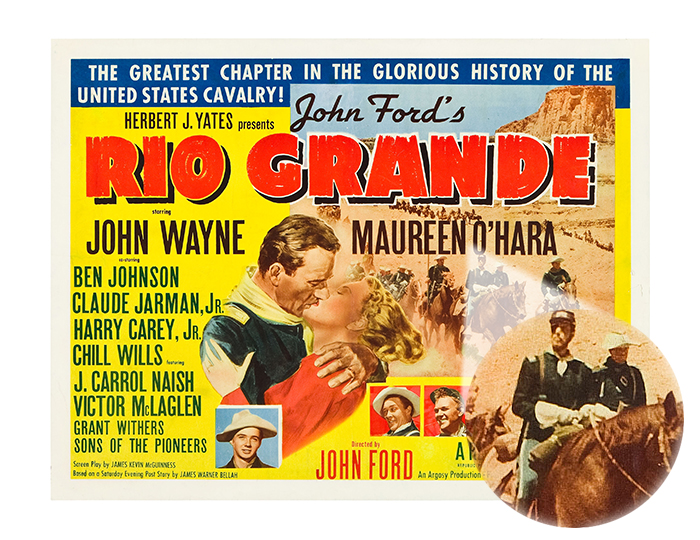

Pierre Ortiz left active duty in 1946, but remained in the Marine Corps Reserve and ultimately retired as a colonel in 1955. Arguably the most decorated of the few Marines to have served in Europe in World War II, he was also among the most successful OSS special operators in the European Theater. He kept up his life of adventure after the war, enjoying modest success as a supporting actor and technical adviser on dozens of Hollywood films and, rumor has it, carrying out the occasional covert mission for the Central Intelligence Agency.

Pierre Ortiz left active duty in 1946, but remained in the Marine Corps Reserve and ultimately retired as a colonel in 1955. Arguably the most decorated of the few Marines to have served in Europe in World War II, he was also among the most successful OSS special operators in the European Theater. He kept up his life of adventure after the war, enjoying modest success as a supporting actor and technical adviser on dozens of Hollywood films and, rumor has it, carrying out the occasional covert mission for the Central Intelligence Agency.

Ortiz spent his final years with wife Jean in Prescott, Ariz., and died of cancer on May 16, 1988. Fittingly, his funeral at Arlington National Cemetery brought together senior American, French and British military leaders and diplomats, all to render final honors to the man whose life was truly the stuff of legend. MH

Laura Homan Lacey [laurahlacey.com] is the author of Ortiz: To Live a Man’s Life. For further reading she recommends Shadow Warriors: The Untold Stories of American Special Operations During WWII, by Dick Camp, and Operatives, Spies and Saboteurs: The Unknown Story of the Men and Women of World War II’s OSS, by Patrick K. O’Donnell.