The swashbuckling Italian American congressman and future New York City mayor proved his mettle in the skies over Italy during World War I.

Fiorello La Guardia was a 35-year-old freshman congressman when the United States went to war in 1917. He had already earned a reputation as a shrewd and ambitious politician with a strong sense of social justice, a fighter against corruption, a defender of the poor and the underdog. But the “Little Flower”—at 5 feet 2, a bundle of volcanic energy and acerbic wit—was little known outside of New York. And he still had much to prove before he could attain the stature that would propel him to three terms as New York City mayor in the 1930s and ’40s.

As the sole Italian American in the 65th Congress, La Guardia was determined to show that the sons of Italian immigrants were as patriotic as other citizens. Having supported President Woodrow Wilson’s declaration of war as well as a controversial draft law, he felt duty-bound to join the military himself. Taking an unpaid leave from Congress, he signed up for the Army’s nascent air service, then part of the Signal Corps.

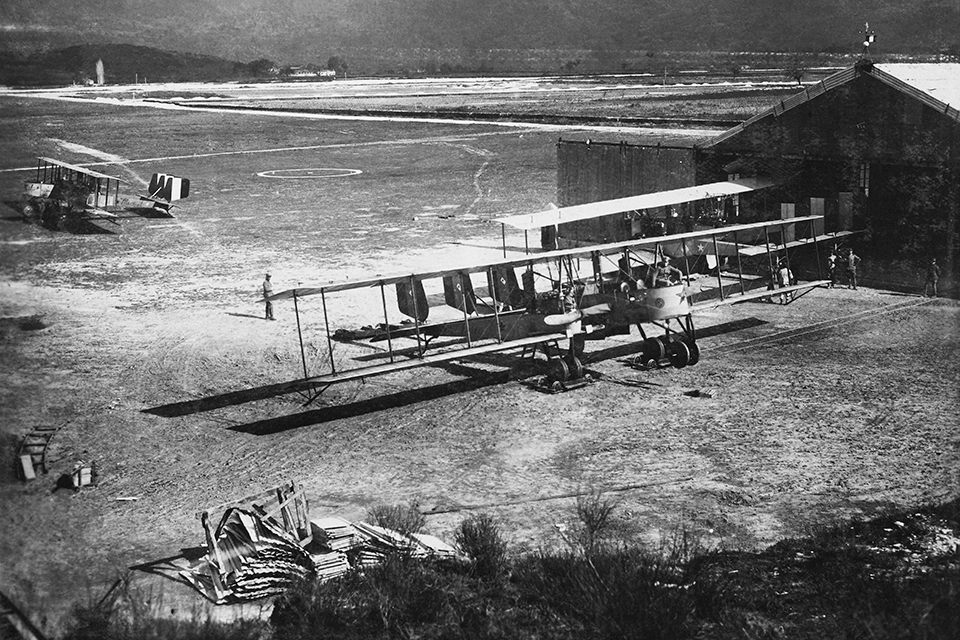

On the brink of war, the U.S. military had only about 50 obsolete aircraft, few flight instructors and not nearly enough trained pilots. The Italian government offered to build a base where American aviation cadets could be given preliminary flight training, under Italian instructors, for service on the Western Front. They chose Foggia, southeast of Rome, which happened to be the birthplace of Fiorello’s father and generations of his family.

La Guardia was a natural choice to head one of the Foggia training camps. He had taken a few basic flying lessons at an airfield in Mineola, on Long Island, in a plane built by his engineer friend Giuseppe Bellanca. Growing up an Army brat on posts out West, La Guardia was familiar with military discipline and routines. And he spoke Italian, New York–style.

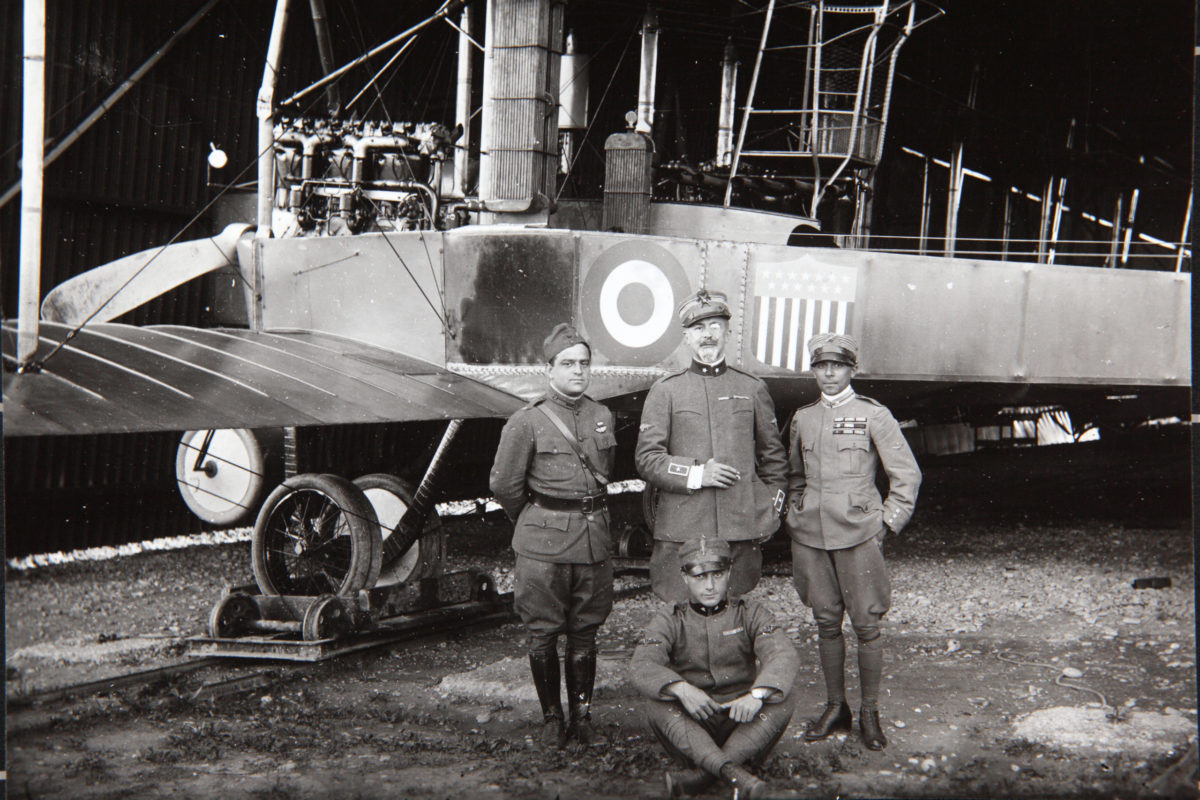

Commissioned a captain, La Guardia was sent to Europe with a shipload of U.S. Army Air Service student pilots going to flight schools in Britain, France and Italy. There were already 46 American cadets at the Foggia base when he arrived in October 1917 with another 125. He became second-in-command to Major William Ord Ryan, who later put him in charge of a second camp established at the school.

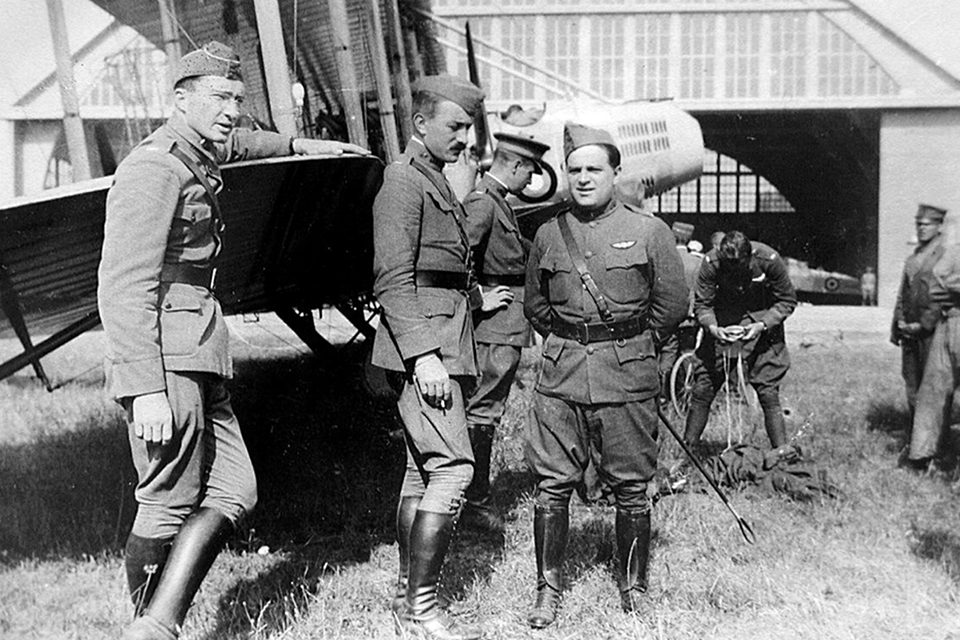

La Guardia’s close-knit fraternity of aviators soon became known as “Fiorello’s Foggiani.” They were an elite group of well-born, well-educated, athletic young Americans attracted to the risks and chivalric glory of aerial warfare. Like his men, La Guardia had been bitten by the flying bug and yearned to prove his mettle and bravery in combat. He would take flight training alongside his Foggiani cadets, and eventually fly missions against the armies of Austria-Hungary and Germany.

The American airmen couldn’t wait to complete the course in Foggia and get into the action. But bad weather and a shortage of planes severely limited their time in the air. Even on a good day, they could hope for at most 10-12 minutes of flight with an instructor. The long downtimes were filled with letters home, repairs and cleanup work, as well as dice and baseball games. (La Guardia coached one team, keeping up a stream of chatter from the sidelines in his high-pitched voice.)

During the journey to Europe, Captain La Guardia had met accomplished violinist Albert Spalding, who had played on some of the world’s most prestigious concert stages. As a young prodigy, Spalding had studied for years in Europe and spoke Italian. La Guardia, from a music-loving family, knew him by reputation and had heard him play. He requested Spalding be assigned to his command.

The tall, slender Private Spalding arrived in Foggia in early 1918 in a tailor-made uniform La Guardia described as “the last word in what a soldier should wear.” He, too, was excited about learning to fly, but La Guardia wouldn’t let him; instead, he made Spalding his adjutant, suggesting that, at 29, he was a little too old for a military pilot (La Guardia himself was nearly 36!). “I wanted a good adjutant—not a mediocre pilot,” he told the violinist. Spalding suspected the real reason was he wanted to spare harm to a “fiddler’s fingers.”

Before soloing, the cadets had to demonstrate various maneuvers with an instructor close at hand. At first, they flew French-made Farman pusher biplanes. Crackups were frequent, from wild landings, engine failures, broken wing ribs and splintered propellers.

Three of La Guardia’s contingent were killed when their two planes collided head-on in a fog bank over the field. Walter Wanger, later a renowned Hollywood film producer, was famous at Foggia for crashing seven planes. He walked away unscathed each time, but, finally, to avoid further losses of expensive equipment, was given a desk job in Rome.

La Guardia himself crashed in a Farman while on a solo cross-country “raid test.” Luckily, his seat belt snapped and he was thrown from the plane before the wreckage and heavy engine could roll over him.

La Guardia had to fit in his own flight trials between administrative duties, but he let nothing stand in the way of his mission and the well-being of “his boys.” When the cadets complained that Italian rations were monotonous and barely enough to sustain them, he hired a caterer to bring in more substantial meals. To cope with swarms of flies and mosquitoes, he had screen doors and windows made for their barracks. And to protect the men against venereal disease, he introduced a course in which he gave lectures on “social disease and commercialized vice,” while a junior medical officer spoke to them about prophylaxis.

La Guardia’s immediate superiors in Italy resented his tendency to use his standing as a congressman to intimidate and go around them. Major Ryan, for one, felt that La Guardia often spoke for the base with higher-ups and the Italian authorities even though Ryan outranked him. The major ultimately filed a report with the Army condemning La Guardia for “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.”

But the top brass recognized La Guardia was a take-charge guy who cut through red tape and moved comfortably among Italy’s most powerful leaders. In February 1918 he was chosen to represent the U.S. Army and Navy Aircraft Board in Italy, with an office in Rome. That made him virtually the commander of training for all American pilots in Italy. It also put him in charge of working with Italian industry to speed up production of badly needed planes, spare parts and materiel for the Italian front.

The obsolete Farmans were to be replaced by a new, experimental version of a lightweight reconnaissance plane, the SIA 7B-1. Built by Fiat’s air subsidiary, the Societá Italiana Aviazione, the SIAs were fast, agile and good climbers. But the new version had structural weaknesses that had already caused the deaths of Italian test pilots. One of the best American aviators, Marine Corps Lieutenant Marcus Jordan, was fatally injured when a new SIA “pulled apart under him” in midair and crashed.

Acting on his own, La Guardia suspended all training on the SIAs. Instead, he recommended that American pilots take advanced training in Caproni Ca.5 heavy bombers ordered by the U.S. government. The Ca.5 was a giant wood-and-fabric aircraft designed by aviation pioneer Gianni Caproni. The main production version, the Ca.44 (also known as the Caproni 600), had a 77-foot wingspan and was powered by three 200-hp Fiat engines—one on each side of the lower wing and a central pusher engine mounted in the rear. The four-man crew consisted of pilot, copilot, front gunner and rear gunner/mechanic.

A fully loaded Caproni carried 17 bombs and enough fuel for 5½ hours of flight, with a top speed of about 100 mph. The Fiat engines could be erratic. “The big Fiat motor on the 600s…had the bad habit of catching fire when throttled down for glides or descents,” wrote Foggiani airman Frederick “Fritz” Weyerhaeuser.

In his autobiography La Guardia called the bomber “as efficient a plane as any then built.” American cadet George M.D. Lewis wrote home excitedly to his girlfriend in Scranton, Pa.: “I am now soloing on the big Caproni—my, but it’s some wonderful machine. I was in the air alone, made a ‘giro’ [circuit, or turn]…and landed like a bird.”

The rout of Italian armies at Caporetto, soon after La Guardia arrived in Foggia, led to an even bigger role for him. By October 25, 1917, Austro-Hungarian armies, reinforced by elite German divisions, had broken through the lines at several points along the border with Italy. Panicked Italian soldiers threw down their weapons and retreated in disarray, joining masses of fleeing civilians on the narrow roads. Upwards of 275,000 Italians were taken prisoner and 10,000 were killed.

At the Piave River, just 15 miles from Venice, the Italians managed to hold the line. But morale in the country had sunk to rock bottom. Shortages of food and worker strikes fueled a peace movement that was growing stronger. The Russians had left the war and the Western Allies worried the Italians might do the same. The Germans were flooding the country with anti-American propaganda.

The Allies had done little up to then to aid the Italian cause; now they were under heavy pressure to show their support by sending troops and aircraft units to assist in throwing back the enemy. General John J. Pershing, supreme commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, hinted that he might send a small force of American soldiers to bolster the Italian counteroffensive, but he didn’t get around to it until a few months before war’s end. The small corps of American aviators was the only visible U.S. military in Italy. Reluctantly, persuaded by La Guardia, among others, Pershing agreed to allow some American pilots to temporarily fly combat missions in Italian squadrons as part of the final phase of their training for action on the Western Front.

Less than a month later, after a big sendoff at Rome’s Hotel Royal, 18 American pilots departed for the front in Padua accompanied by La Guardia. There they were assigned to Caproni squadrons and crews, and on June 20, 1918, a group of the Americans took off on their first mission, flying over the lines to bomb a bridge on the Piave and cut off retreating enemy forces.

La Guardia did not participate in the first raid because he was not yet qualified to fly combat missions. After returning to his office in Rome, he was called on by U.S. Ambassador Thomas Nelson Page to throw his talents into the war on another front: the propaganda campaign to convince Italians not to give up the fight.

La Guardia addressed patriotic rallies in major cities up and down the peninsula, urging Italians to redouble their efforts to win the war. Crowds of as many as 200,000 people stamped and clapped and roared their approval. Despite his street-pidgin Italian, the crowds loved this son of Italy wearing the uniform of the United States, a symbol of Italian success in America. The stocky Latin orator was sometimes joined by his Italian-speaking sidekick, Spalding—tall, Anglo-Saxon—the American melting pot on full display.

While assuring Italians of American help, La Guardia also scolded them in terms rarely heard in the country. Italians ate too much, didn’t work enough, tried to evade military service. They had diverted funds from U.S. loans meant for the war effort to “build buildings.” Financial “slackers” had failed to support the Italian war loans. “You either win this war and preserve your place among nations,” he warned them, “or you will become the gardeners of Germany.”

These speech-making trips, often involving two nights away from Foggia, cut into La Guardia’s flight training. Somehow, however, he put together the 180 minutes of air time needed to graduate from basic training. Only one obstacle remained: a pilot endurance test challenging La Guardia to keep his machine in the air as long as he could on a single flight.

Two journalists who knew him, Lowell Limpus and Burr Leyson, described La Guardia’s hair-raising experience as he took the exam in a patched-up Caproni that had been wrecked in combat. Four hours into the flight, “there was a sudden, rending crash—and the crankshaft splintered.” La Guardia quickly cut the ignition to prevent flying engine parts from tearing the aircraft apart. He managed to nurse the bomber back to earth intact, landing in a swamp. His Italian instructors assessed this performance as proof of his ability; in late August they cleared him for combat. At the same time, his promotion to major came through.

La Guardia took part in bombing missions across the lines a total of five times, at least twice at night, all in September 1918. His total combat time was 10 hours and 20 minutes. He usually flew with two of Italy’s best aviators as chief pilot: Major Piero Negrotto, a member of the Italian parliament, and Captain Federico Zapelloni, an Italian bombing ace. They called their Caproni the Congressional Limited, and dared enemy gunners to try to bring it down. The Austro-Hungarians did their best, without success.

La Guardia had a close call during his very first mission, on September 13, to bomb the Austro-Hungarian air base at Pergine. Seventeen Italian bombers were to lure enemy fighters into the skies, where a flock of British and Italian pursuit planes high above the bombers could swoop down and pick them off. But to the surprise of the attacking Italians, the fighters were slow to take off and never made it into the air. The Capronis unloaded their bombs, decimating the field and the planes still lined up on it.

La Guardia filed this terse report on his participation in the mission: “Enemy fire intense and accurate. Plane hit twice in left wing. Right-hand pilot. One large bomb hit on hangar. The rest seem to have gone to the right. Enemy fire on return, accurate and intense.”

Years later, Lieutenant Donald G. Frost, a Foggiani airman who had seen the plane after it landed, took issue with La Guardia’s account: “Plane hit twice! Hell! Why, I saw it myself, and there were over two-hundred holes in it! His machine gun had a piece of shrapnel right through the magazine. It was a wonder he wasn’t blown

to shreds!”

La Guardia was never really a polished flier, but the Foggiani—as well as the Italians—loved him for his guts. Lieutenant Willis S. Fitch described La Guardia’s response to an airman who asked how he was doing with the Caproni: “I can’t take the buzzard off, and I can’t land him, but I CAN FLY the son of a gun!” Fitch suggested La Guardia was being overmodest. His takeoffs and landings were sometimes ragged, he wrote, “but they showed his daring.”

Of the 450 American pilots trained in Foggia, about 80 were kept behind to fly on the Italian front. They took part in 65 missions, for a total of 587 hours in combat. Teamed with Italian fliers aboard the Capronis, they bombed Austro-Hungarian troop concentrations, airfields, bridges, rail lines, munitions depots, and naval bases and factories on the Adriatic.

Only two American airmen lost their lives on the Italian front. Lieutenants Dewitt Coleman and James L. Bahl Jr. were killed with their Italian crewmen just a few days before the armistice was declared. Their Caproni 600 set out with seven other bombers on the afternoon of October 27 to support Italian forces at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto. Separated from the squadron, their Caproni was engaged by five enemy fighters. In a furious running battle, they drove down two before their riddled aircraft went down in flames.

The Italians’ decisive victory at Vittorio Veneto led to the final collapse of the Austrian-German army, and on November 3 Austria—abandoned by Hungary as of October 31—agreed to an armistice. La Guardia had been ordered to return to the U.S. in October for a mission that proved unnecessary. Meanwhile, favorable press coverage of his role on the Italian front had earned him nationwide acclaim as the “American congressman-aviator.”

Almost immediately he went to work campaigning to preserve his seat in Congress. Critics in his district had been attacking him for leaving his voters unrepresented while abroad. There was also substantial antiwar sentiment among district voters. Nevertheless, La Guardia soundly defeated his opponent.

The irony of Fiorello La Guardia’s service in World War I is that he had always said he was against war. He had volunteered for service—and dropped bombs—to end wars, to fight for democracy. La Guardia remained a staunch pacifist throughout his life, fervently promoting many peace causes. Nations, he argued, wasted millions of dollars on wars better spent helping needy and oppressed peoples around the world.

Barely a decade and a half after the Wright brothers flew at Kitty Hawk, the Foggiani had shared the exhilaration of flying above snow-capped peaks, winding rivers and deep gorges. The experience left some of them with conflicting emotions. “The sheer beauty of it all gave one a feeling of unreality and of being in a dream…,” Fritz Weyerhaeuser, a Yale graduate and heir to a lumber empire, told his biographer. “It seemed impossible that the killing of people could be the reason for flight through such a paradise.”

Howard Muson is a journalist whose career spanned stints at Associated Press, Time magazine and The New York Times. Further reading: The Making of an Insurgent: An Autobiography, 1882-1919, by Fiorello H. La Guardia; This Man La Guardia, by Lowell M. Limpus and Burr Leyson; and Wings in the Night: Flying the Caproni Bomber in World War I, by Willis S. Fitch.

This feature originally appeared in the September 2020 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!