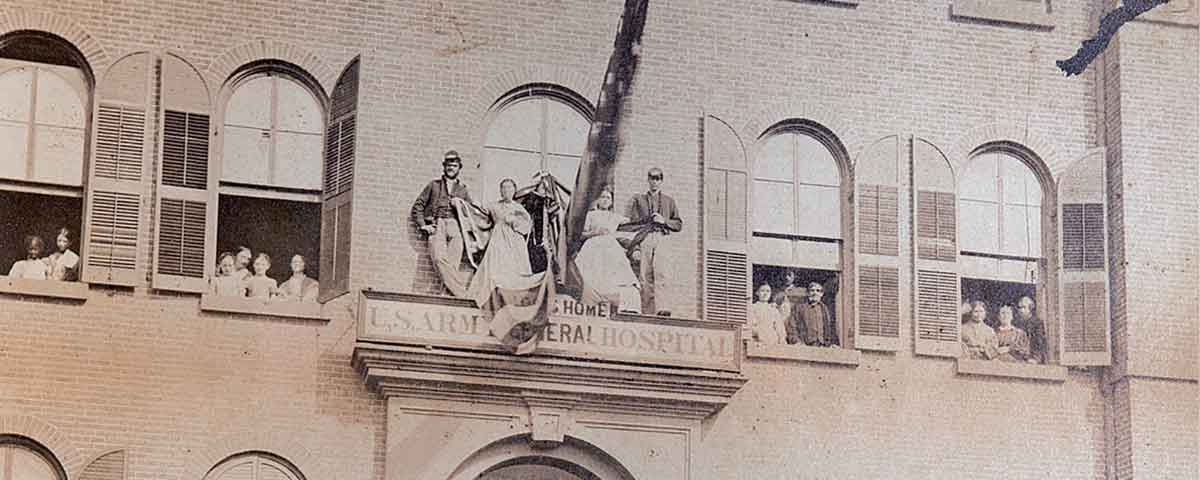

A remarkable 1865 photograph captures the staff and residents of a New York City hospital

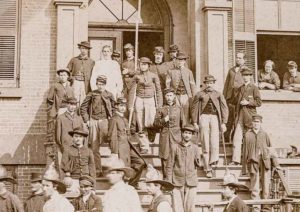

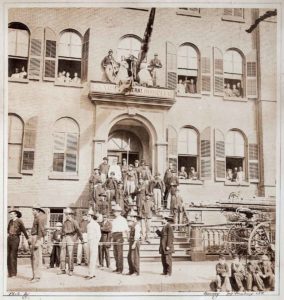

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n a bright, sunny June 1865 day, Union veterans scarred by war posed on the steps of the Ladies Home U.S. Army Hospital located at the corner of New York’s Lexington and 50th streets, on Manhattan’s east side. At least six of the soldiers were missing arms and three more were missing a leg or foot. Some may have been hiding their disfigurements and wounds behind others on the stone steps. They were the last of the hospital’s inmates, as the institution, which had opened in 1861 and had treated more than 4,000 soldiers during the war, was set to close the same month. The men would soon have to cope with their new physical realities in civilian life.

But on this day, they put on brave faces and posed with their caregivers and their temporary neighbors, a total of 55 people, 14 females and 39 males, at the front door of the hospital that had helped their recovery. They had assembled so that the photography studio of Jeremiah and Benjamin Gurney, best known as Gurney & Son, could take this fascinating albumen photograph.

But on this day, they put on brave faces and posed with their caregivers and their temporary neighbors, a total of 55 people, 14 females and 39 males, at the front door of the hospital that had helped their recovery. They had assembled so that the photography studio of Jeremiah and Benjamin Gurney, best known as Gurney & Son, could take this fascinating albumen photograph.

The image is one of only five known New York City street views taken by that studio, which had opened as one of the first daguerreotype studios in the country in 1840. The firm claimed that their 707 Broadway studio was the oldest in the United States and the first built in America exclusively for the purpose of photography. It was located less than 2.5 miles from where this image was shot. On April 24, approximately eight weeks prior to this photo being taken, Benjamin Gurney had taken an even more momentous image when he photographed the only known view of assassinated President Abraham Lincoln as he lay in his casket at New York’s City Hall.

The Rev. James Tuttle Smith, the hospital’s chaplain who is present in the large, approximately 14.5-inch wide by 15.5-inch tall photo, was the proud owner of this image. His name, “J. Tuttle Smith, Chaplain U.S. Army,” is inscribed on the photo verso and also on a small tag mounted to the back of the mahogany frame.

We don’t know the names of these men, but we can look at their faces and wonder where they suffered their injuries. Was it in a titanic fight like Gettysburg or the Wilderness? Or did a random shot along an unnamed picket line forever alter their lives? Perhaps a simple scratch refused to heal and became infected. We do know the names of several of the caregivers that helped the veterans recover so they could be sent back into the world and an uncertain future, some to limp their way through tasks that had once been effortless, and some to struggle to cut their food with one hand.

One of 10,000

An African American child, one of 9,945 African Americans known to live in New York City in 1865, poses with other children in the upper windows of the hospital.

Doctors in the House

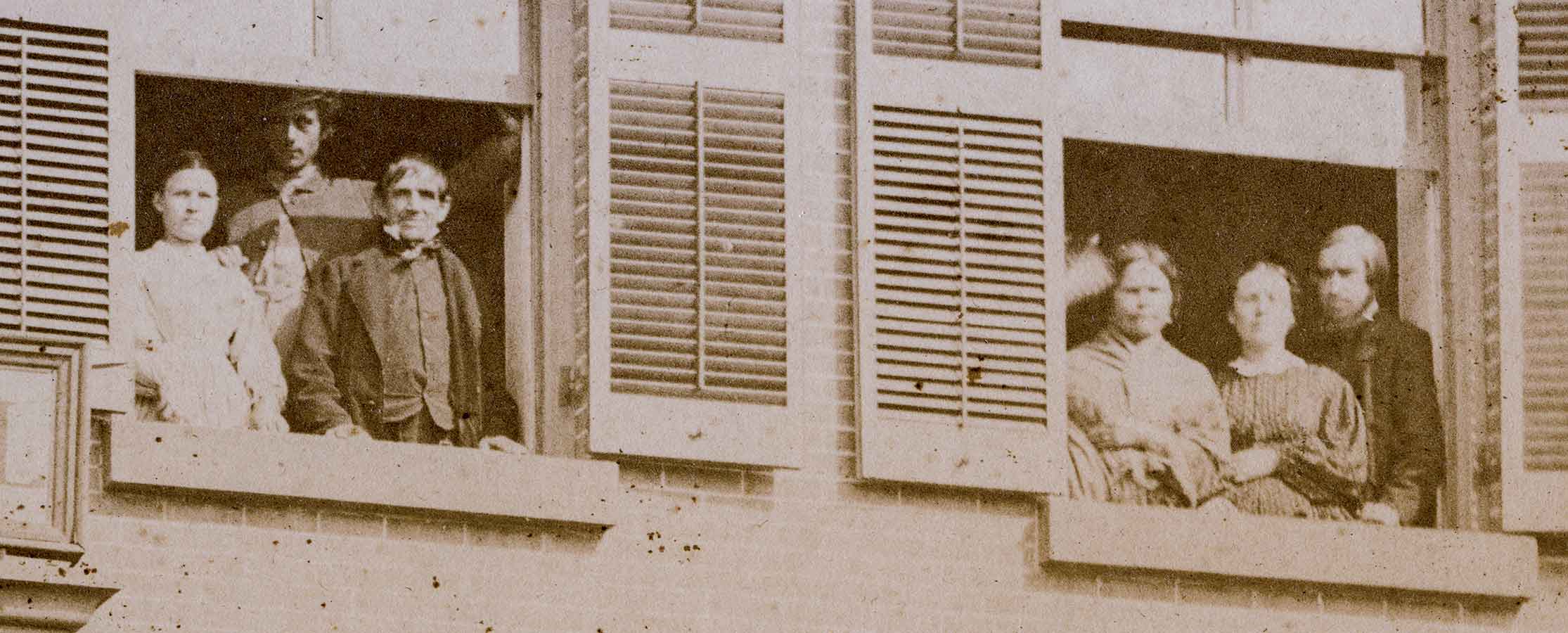

Gurney photographed most of the doctors and faculty of New York’s Bellevue Hospital, and based on a comparison with one of those images, it is possible that the man at the far right of the right window is Dr. Henry Drury Noyes, an ear and nose doctor. The image is just blurred enough to make a positive identification impossible. Nursing was a pioneering field during the Civil War, and the other women in the windows might be nurses, members of the Sanitary Commission, or simply hospital visitors.

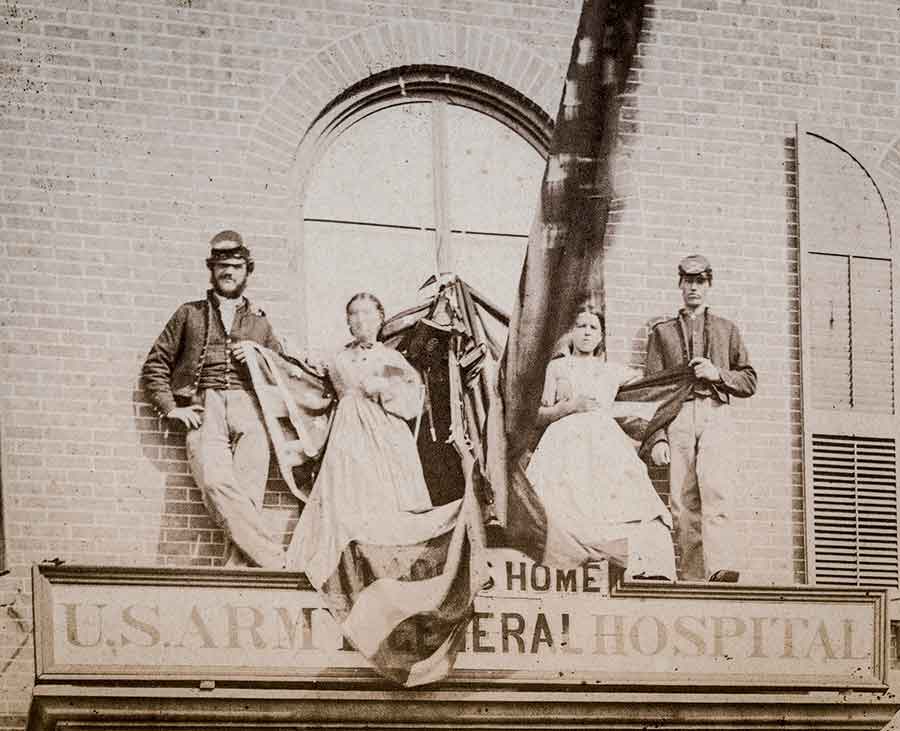

All For The Union!

Soldiers and two women form a tableau to liberty on the covered porch. Note the rifles gathered at the base of the large United States flag. Both the soldiers flanking the flag have crossed cannons on their forage caps, similiar to the one at left, indicating that they are artillerymen.

Empty Sleeves and Hollow Trousers

At least nine amputees are on the hospital steps. Generally speaking, the patients look to be fairly healthy and at the end of their recuperative process, but it is impossible to say how they actually feel and how long they have spent in the hospital. At full capacity, the hospital had room for 400 patients. It’s interesting to note the armed guard at the top of the steps. The 1863 Draft Riots indicated that not all of the city’s residents were sympathetic to the Union, so it didn’t hurt to have some security around. The man wearing white clothing could be a patient in hospital clothing, a civilian steward, or a soldier in his issue undershirt.

Man of God

A large cross hangs from the neck of Chaplain James Tuttle Smith, the original owner of this image.

Air of Authority

The shoulder boards and button grouping on the front of this officer’s coat indicate he is a major. His central location on the steps, as well as his right hand thrust into his coat, a classic Napoleonic pose, designates him as someone in charge, perhaps the commander of the hospital.

‘Sawbones’

The man standing in front of the shutter at the top right of the steps bears a resemblance to hospital Assistant Surgeon Dr. Charles Carroll Lee.

Signalman

Signalman

This soldier missing a portion of his left leg wears the uncommon jacket distinctive to the Union Signal Corps. The short jacket featured 11 buttons down the front and a patch bearing crossed signal flags on the left arm.

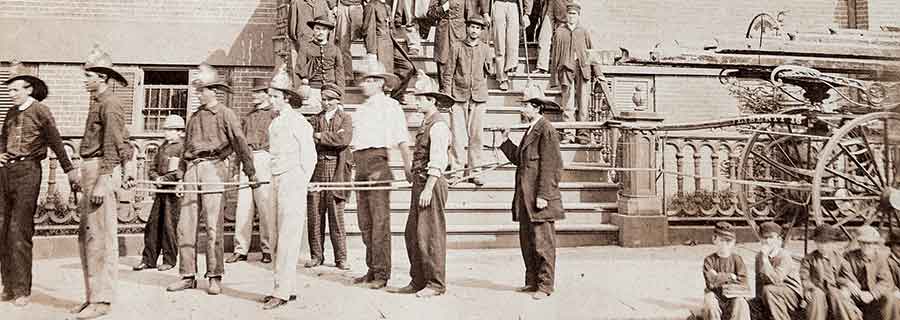

Fire! Fire! Fire!

Seven New York volunteer firemen from Liberty Hook and Ladder No. 16 pose with their engine in front of the hospital. Their station was located next door at 136 Lexington Avenue and their Fire Captain, Robert Gamble, also served as New York City’s coroner at the time. The engine’s sign plate is preserved at the Smithsonian Institution.

School is Out

Young boys with school books sit on the curb. Perhaps they regularly walked past the hospital on their way to and from school.

Terry Alphonse is a collector of early photography who specializes in images taken by the studios of J. Gurney & Son, 1840-1876. He resides in Michigan.