The cheering Korean crowds were enough to stop any man in his tracks—even the president of the United States. South Korea was the final layover on Lyndon Johnson’s 17-day, seven-nation tour of Asia in the fall of 1966, and he had come primarily to thank President Park Chung-hee for having committed 45,000 Korean troops to the Vietnam War effort.

Johnson’s motorcade through the streets of Seoul drew an estimated 2 million spectators, with crowds 30 people deep lining the entire route. A few individuals were reportedly trampled as onlookers waved U.S. and South Korean flags alongside homemade banners welcoming the “Texas cowboy” and wife “Bluebird” to Seoul. Ever the politician, Johnson had his driver stop the open car several times so he could shake hands with spectators en route to Seoul’s City Hall. There he gave a speech commending the people on having rebuilt their nation since the 1950–53 Korean War and proffered his thanks for joining the fight in Vietnam. Lyndon and Lady Bird then attended a state dinner in their honor followed by a program of traditional Korean folk songs and dances. The next day Johnson was scheduled to inspect troops of the Korean 26th Infantry Division and U.S. 36th Engineer Group before lunching with American enlisted men at Camp Stanley, in Uijeongbu, a dozen miles north of the capital.

As the first couple slept that night in Seoul’s Walker Hill resort complex for U.S. servicemembers, American soldiers were fighting and dying in combat scarcely 30 miles way.

The 1953 armistice that halted the Korean War did not officially end the conflict, but it did establish a 160-mile-long, roughly 2.5-mile-wide demilitarized zone dividing North and South Korea. Troops of the Republic of Korea safeguarded the southern side of the DMZ, save for an 18-mile section patrolled by the U.S. Army. From 1953 through October 1966 only eight Americans had been killed in border clashes with the North. Tensions on the DMZ had ratcheted up in the weeks before Johnson’s visit, however, and U.S. and allied intelligence organizations were certain the uptick was tied to South Korea’s deepening involvement in Vietnam. The Central Intelligence Agency and U.S. military services pointed to an unequivocal October 5 speech by North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Il-sung to the ruling communist Workers’ Party of Korea, in which he pledged to “render every possible support to the people of Vietnam” warned the status quo between the two Koreas was about to change, and insisted “U.S. imperialists should be dealt blows.”

By the time of Kim’s speech North Korea had deployed eight infantry divisions along its side of the DMZ. Eight additional infantry divisions, three motorized infantry divisions, a tank division, and various infantry and tank brigades were on standby. In addition to conventional forces, North Korea deployed the 17th Foot Reconnaissance Brigade and the 124th and 283rd Army Units, each broken down into two- to 12-man teams armed with either submachine guns or AK-47 assault rifles. North Korean personnel strength on the border was estimated at around 386,000. Facing them were upward of 585,000 South Korean and U.S. troops. Unconventional warfare seemed Kim’s preferred recourse.

In the predawn darkness of November 2, as President Johnson and the first lady slumbered in Seoul, North Korean soldiers armed with grenades and submachine guns slipped through the DMZ

In the predawn darkness of November 2, as President Johnson and the first lady slumbered in Seoul, North Korean soldiers armed with grenades and submachine guns slipped through the DMZ and ambushed a United Nations patrol comprising seven Americans from the 2nd Infantry Division and an accompanying South Korean. Though the members of the patrol fought fiercely, all but 17-year-old Pfc. David Bibee were killed. Wounded by shrapnel, Bibee played dead while the Koreans looted the bodies. “The only reason I’m alive,” he later said, “is because I didn’t move when a North Korean yanked my watch off my wrist.” (Hours later North Korean infiltrators ambushed another patrol in the area, killing two South Korean officers.)

Johnson learned of the incident later that day as he and Lady Bird boarded their stateside-bound plane in Seoul.

The November 2 ambush killing of American soldiers marked the catalyst of the Korean DMZ Conflict (aka Second Korean War), which would stretch through 1969.

Commanding U.N. forces in South Korea at the time was U.S. Gen. Charles Bonesteel III, who formed a working group to develop a counterinsurgency strategy. He had his work cut out for him. The Pentagon hamstrung Bonesteel from the start, making no secret of the fact his command was third in line for troops and materiel after Vietnam and the U.S. commitment to NATO in West Germany. His primary concern was to keep a lid on tensions along the DMZ, as there was certainly no love lost between the two Koreas.

In mid-October 1966, weeks before Johnson’s visit, North Korean infiltrators had attacked two South Korean patrols south of the DMZ, killing 17 soldiers. South Korea had promptly retaliated, sending an attack team north of the DMZ, which killed 30 North Korean troops. On Jan. 19, 1967, North Korean shore batteries sank a South Korean patrol boat that had strayed north of the maritime demarcation line in the Sea of Japan (or East Sea in Korean), killing 39 sailors and wounding 15. In April along the DMZ South Korean units used artillery for the first time since the armistice to repel an incursion of several dozen North Koreans.

Meanwhile, attacks on Americans continued. In February one U.S. soldier was killed along the DMZ when a U.N. patrol came under North Korean fire. On May 22 North Korean infiltrators set off demolition charges at the U.S. 2nd Infantry Division barracks, killing two Americans and wounding 19 other soldiers. Attacks killed eight more U.S. soldiers that summer. In September saboteurs dynamited two South Korean trains, one carrying U.S. military supplies.

The fighting spread beyond the DMZ. On June 19 four South Korean policemen and a civilian were killed in a firefight with North Korean infiltrators near Daegu, toward the southern end of the peninsula. By then South Korean intelligence officials were warning U.S. leaders North Korea sought to spark a subversive movement against Seoul and Washington, similar in tactics and execution to an offensive North Vietnamese communists were then hatching against South Vietnam.

As the number of attacks escalated that summer, Bonesteel called in U.S. special forces teams from Okinawa to engage the infiltrators and train South Korean soldiers and police in counterinsurgency tactics. From May 1967 through January 1968 U.S. forces alone logged some 300 enemy engagements south of the DMZ that left 15 Americans dead and 65 wounded.

The most serious North Korean incursion to date came on January 17, when all 31 members of the 124th Army Unit cut through the wire along the DMZ and fanned out into the South Korean countryside. Their orders from Lt. Gen. Kim Chung-tae were blunt: “Go to Seoul and cut off the head of Park Chung-hee.” By killing the South Korean president, the North hoped to throw its sister nation into chaos and spark a revolt aimed at reunification.

Two days later four South Korean brothers out cutting wood stumbled across the unit. Instead of killing the brothers, the North Korean commander sought to indoctrinate them into the communist cause. He then released the four, warning them not to betray the unit’s presence. Unbowed, the brothers immediately notified South Korean authorities, and by the next morning the national police and South Korean military were on full alert. The unit eluded all searchers.

Entering Seoul in small teams on the night of January 20–21, the North Koreans changed into South Korean army uniforms to pose as a unit returning from patrol. By 10 p.m. that evening they had passed through several checkpoints on the road to the Blue House—the presidential residence. The unit had closed to within 100 yards of its intended target, when a local police chief approached and questioned the men. Suspicious of their answers, he drew his sidearm, but the infiltrators shot him dead. Other policemen returned fire, killing two North Koreans and sparking a running gunfight as the unit dispersed, fleeing north toward the DMZ. Over the next eight days U.S. and South Korean troops scoured the area for the infiltrators, engaging in several firefights. Only one North Korean ultimately made it back across the DMZ; 25 others were killed, one committed suicide, one was captured, and one vanished. Four American soldiers and 26 South Koreans died in the fighting; 66 others were wounded, including two-dozen civilian bus passengers caught in the initial crossfire.

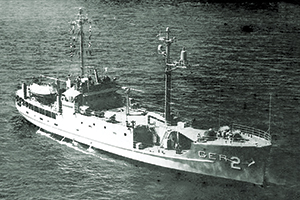

On January 23, two days after the assassination attempt, North Korean patrol boats operating in the Sea of Japan fired on and seized the American reconnaissance vessel Pueblo in international waters, killing one crewman. By the time the United States was able to mount a response, the ship was under guard in the North Korean port of Wonsan. Its 82 surviving crewmen were soon spirited off to inland POW camps.

A week later North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops launched the Tet Offensive against more than 100 towns and cities in South Vietnam. They targeted provinces with an active South Korean military presence, likely hoping to provoke further reaction along the Korean DMZ.

The assassination attempt in Seoul and the capture of Pueblo prompted Johnson to order a show of force off the Korean peninsula, a demonstration involving a half-dozen aircraft carriers and their embarked fighter squadrons. The president also ordered a partial mobilization of military reservists—the first such directive since the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

Meanwhile, North Korea’s provocative actions seemed to be eliciting at least one desired response—discord between the United States and South Korea. Seoul floated the idea of withdrawing its troops from Vietnam in order to reinforce its own position against the communist North, and South Korean leaders openly discussed retaliatory strikes north of the DMZ. The rising tensions also prompted Park’s government to cancel the deployment of a third ROK division to Vietnam. Operating behind the scenes, the Johnson administration pulled diplomatic strings to prevent both a retaliatory strike from Seoul and a South Korean withdrawal from Vietnam. At the same time, Johnson extended the tours of South Korea–based U.S. troops, while also diverting thousands of Vietnam-bound American soldiers to the peninsula.

U.S. commanders moved two brigade headquarters, four battalions from the 2nd Infantry Division and one battalion from the 7th Infantry Division to face communist troops directly north of the Imjin River, which flows across the DMZ and joins the Han River, which leads upriver to Seoul. Early in the Korean War primarily British elements of the U.N. forces defending the waterway slugged it out against Chinese troops to keep Seoul from falling to the communists. South of the 2nd Infantry Division positions along the Imjin, the 7th Infantry Division moved into the mountains and dispatched foot and air patrols intended to thwart infiltrating North Koreans. Regardless, isolated radio relay sites soon came under attack. Short on manpower, the 7th reinforced the vulnerable outposts with scouts, cooks, supply clerks and medics. To reduce the potential of ambush, plows continually cleared roadsides leading to and along the border, while aircraft sprayed defoliants.

The personnel shortages in Korea-based American units were, of course, a result of the priority given to operations in Vietnam. In an effort to fill out vacancies in Korea, qualified junior enlisted soldiers were sent to noncommissioned officer academies, and promising NCOs received field promotions to lieutenant. To improve combat readiness, the two divisions along the Imjin also undertook intensive refresher training in light infantry and counterinsurgency tactics. The training proved timely, as in 1968 alone U.S. and South Korean troops engaged the enemy in some 700 firefights and captured 1,245 North Korean agents south of the DMZ.

The hardening of the DMZ prompted Pyongyang to mount an amphibious operation against South Korea that fall, aimed at establishing guerrilla camps in the Taebaek Mountains. After midnight on October 30 patrol boats dropped 120 commandos at eight predetermined locations along the eastern coast. After failing to indoctrinate local villagers, the infiltrators were forced to flee for their lives in the face of a massive manhunt by South Korean and U.S. forces. More than 100 North Koreans were killed for a loss of 40 South Korean soldiers, policemen and militiamen, three U.S. troops and 23 civilians. Like the earlier assassination attempt in Seoul, the operation was a fiasco for Pyongyang.

To further reassure Seoul, the Johnson administration also secured from Congress $100 million in special military aid to South Korea, on top of $32 million in equipment and a $12 million loan for industrial development. In return, Park agreed not to go north.

Military analysts floated various theories to explain why North Korea discontinued its cross-border operations. Some believed Pyongyang had lost the backing of China

The Johnson administration’s doubling down in Korea slowly began to show positive results. Following extensive negotiations regarding the fate of Pueblo’s crew—including an almost immediately retracted U.S. admission they had been conducting espionage operations—North Korea finally released the men. Shuttled among various POW camps, they had undergone torture and deprivation for 11 months. On Dec. 23, 1968, bearing the body of the sailor killed during Pueblo’s capture, the 82 survivors walked to freedom across the “Bridge of No Return” at Panmunjom. (Pueblo remains in North Korean hands, serving as a museum ship along the Potong River in Pyongyang; it also remains a commissioned vessel in the U.S. Navy.)

Still, the situation remained tense. On April 15, 1969, a North Korean MiG-21 fighter shot down a U.S. Navy Lockheed EC-121M Warning Star reconnaissance aircraft, killing all 31 men aboard—the worst single loss of a U.S. aircrew during the Cold War. The newly installed administration of President Richard Nixon responded to the provocation by stationing a 23-ship task force in the Sea of Japan and making it known intelligence flights would thereafter have fighter escorts.

That year the number of hostile incidents by the North dropped to little more than 100. Then, suddenly, the fighting was over. North Korea attempted no more mass incursions. The undeclared war had cost the lives of 43 American soldiers, 299 South Korean troops and nearly 400 North Korean soldiers and agents.

Military analysts floated various theories to explain why North Korea discontinued its cross-border operations. Some believed Pyongyang had lost the backing of China, as a distracted Beijing had seen a concurrent increase in tensions with the Soviet Union—tensions that twice led to an exchange of fire along the China-Siberia border. Others posit North Korea ultimately accepted the failure of its own disruption campaign, as the South Korean people never rose against their own government.

Whatever the reasons for the winding down of the conflict, it is officially considered to have ended on Dec. 3, 1969, the day North Korea released three captured U.S. Army aviators whose Hiller OH-23 Raven helicopter had been shot down four months earlier after having strayed into enemy airspace. Nearly a half-century would pass before leaders on either side made serious inroads toward ending the broader Korean War. On April 27, 2018, South Korean President Moon Jae-in met with North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un on the south side of the Joint Security Area in the DMZ. The two leaders adopted the Panmunjom Declaration, pledging to cease all hostile acts and seek a formal end to the war. Whether tensions along the DMZ will keep in check remains to be seen. MH

Mike Coppock writes from Enid, Oklahoma. For further reading he recommends Scenes From an Unfinished War: Low-Intensity Conflict in Korea, 1966–1969, by Maj. Daniel P. Bolger; “The Forgotten DMZ,” by Maj. Vandon E. Jenerette, available online [koreanwar.org]; and “The Quiet War: Combat Operations in the Korean Militarized Zone, 1966–1969,” by Nicholas Sarantakes, also available online [sarantakes.com].