Painting in American Indian culture has long been a means not only of artistic expression but also of recording tribal history. Surviving rock art, hide paintings and ledger art most often record significant accomplishments and noteworthy tribal events. The 20th-century artists known as the Kiowa Five (or Six) doubtless drew inspiration from such works, but their chosen medium was watercolor, and they offered a broader range of expression.

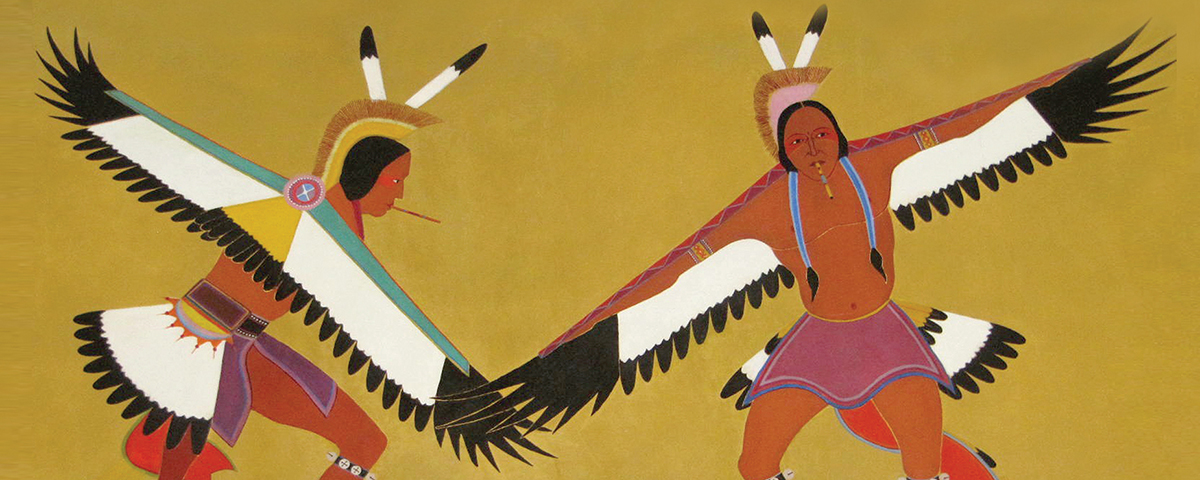

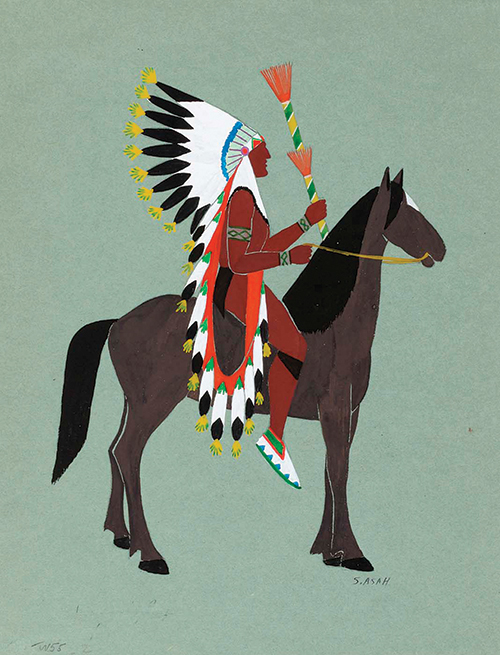

They worked in flat style, their scenes lacking perspective, the result of leaving the background empty and rendering full figures of people using bold colors. Rarely was there any softness or blending for dimension. They drew figures with sharp, well-defined outlines filled in with solid, flat paint in brilliant tints, a technique known as pochoir (French for “stencil”). Common subjects included hunting and dancing scenes, cultural paraphernalia and tribal symbolism. Larger murals often depicted everyday village life. Most evoked a sense of animation.

Thanks to early recognition of their artistic skills and support from specific individuals, the Kiowa artists ultimately achieved domestic and international acclaim. At St. Patrick’s Mission School in Anadarko, Okla., five of the group received art lessons from Choctaw-Chickasaw nun Sister Mary Olivia Taylor (1872–1931). Around 1920 Susan Peters, a field matron at the Anadarko Indian Agency, formed an art club to augment their skills. But it wasn’t until Peters brought them to the attention of Oscar Jacobson, director of the University of Oklahoma School of Art in Norman, that their potential truly blossomed.

The Kiowa artists lacked the basic qualifications to enroll in the school, so Jacobson bent a few rules. He and fellow professor Edith Mahler gave them technical instruction, and Jacobson provided them studio space and encouraged them to develop their own signature style. In 1928 he arranged to have some of their watercolors exhibited at the International Congress for Art Education, Drawing and Applied Arts in Prague, Czechoslovakia. The next year he had a folio of their work published in France. Back stateside in the early 1930s they received commissions for murals in public spaces such as the State Historical Building in Oklahoma City, the Federal Building in Muskogee, Okla., the Department of the Interior Building in Washington, D.C., and their local Anadarko Post Office.

The Kiowa artists lacked the basic qualifications to enroll in the school, so Jacobson bent a few rules. He and fellow professor Edith Mahler gave them technical instruction, and Jacobson provided them studio space and encouraged them to develop their own signature style. In 1928 he arranged to have some of their watercolors exhibited at the International Congress for Art Education, Drawing and Applied Arts in Prague, Czechoslovakia. The next year he had a folio of their work published in France. Back stateside in the early 1930s they received commissions for murals in public spaces such as the State Historical Building in Oklahoma City, the Federal Building in Muskogee, Okla., the Department of the Interior Building in Washington, D.C., and their local Anadarko Post Office.

So, who were the Kiowa Six? All were men except for Lois Smoky (1907–81), the youngest of the group. Smoky felt out of place among the male artists, as Kiowa women of the era were expected to pursue beadwork and basket weaving. She soon left to start a family. As Smoky painted fewer pieces than the others, her works are the most widely sought and valued.

The oldest member, Stephen Mopope (1898–1974), was the great nephew of ledger artist Ohettoint. Mopope was the most prolific of the Kiowa Six, known not only for his artwork but also for his “fancy dancing” and flute playing. Music often appeared as a motif in his works.

Jack Hokeah (1902–69) was another artist who showed an appreciation of and talent for dancing, a sideline that informed his paintings. He demonstrated a greater mastery of design than the other Kiowa artists, his figures conveying a sense of movement.

Monroe Tsatoke (1904–37) had an interesting lineage. His father, Hunting Horse, had served as a Kiowa scout for Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer, while one of his grandmothers had been a white captive. Though Tsatoke suffered from tuberculosis and died at age 32, he credited his illness with a spiritual awakening and often painted about his religious experiences.

Spencer Asah (1905–54), the son of a medicine man, was raised to respect the close ties of his people to the land and the buffalo, and his paintings reflect obvious influences of Kiowa culture. He, too, counted dancing as a favorite pastime, an interest reflected in his paintings.

The last member to join the group, James Auchiah (1906–74), replaced Smoky when she left the group in 1927. His grandfather was Satanta, the respected Kiowa war chief, and his work is rife with tribal symbolism. Beyond his career as an artist Auchiah served in the Coast Guard during World War II, taught some and worked as a museum curator.

To be a great painter was to be an acclaimed recorder of history of noteworthy events—and the importance of such a person to the tribe cannot be understated. The style of the Kiowa Group, whatever its beginning, is unmistakable and continues to influence Plains Indian artists who followed. WW

Canadian freelancer Les Kruger, a retired teacher from Ontario, spends much of his time traveling and researching in the American West.