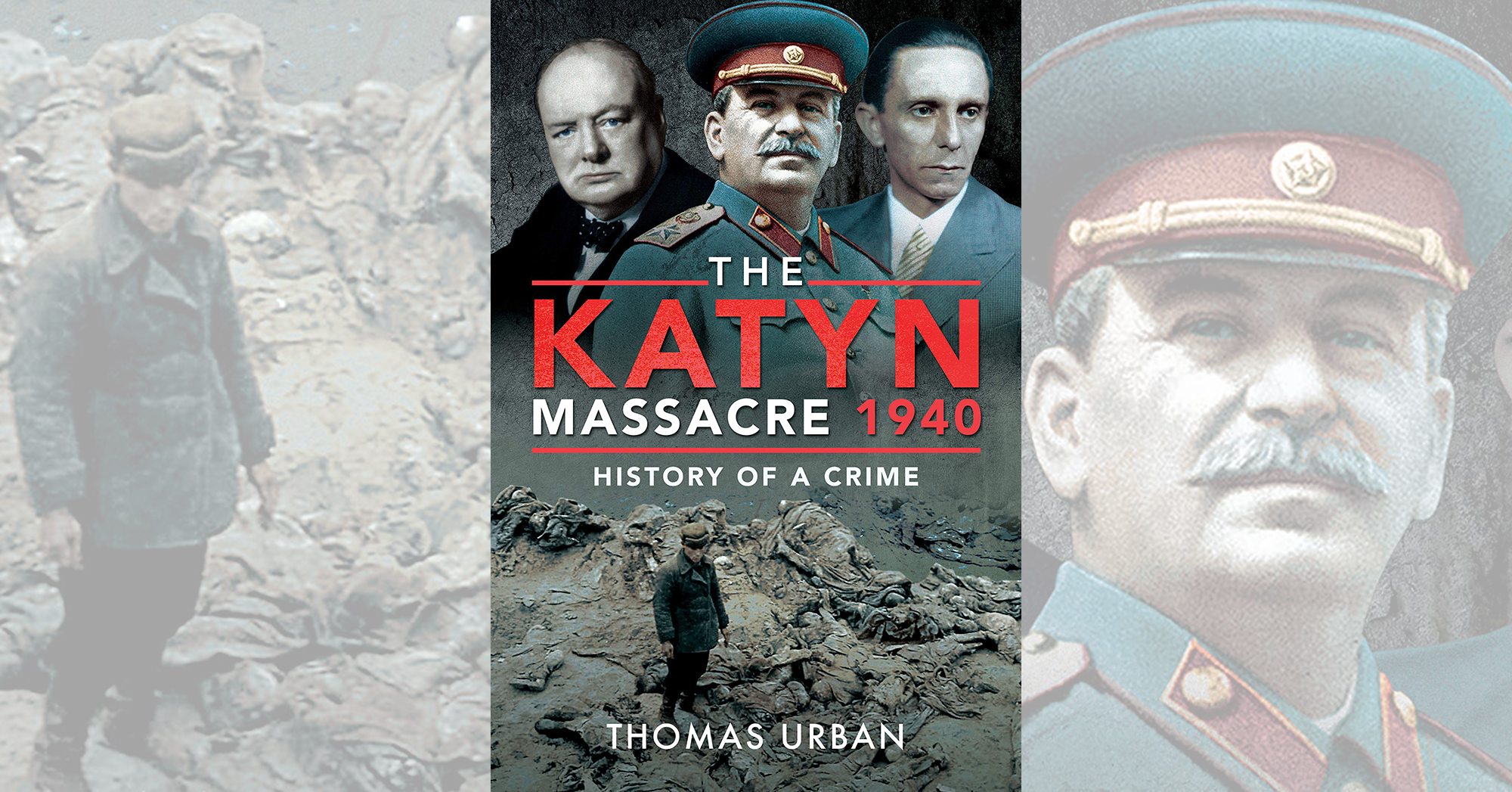

The Katyn Massacre, 1940, by Thomas Urban, Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley, U.K., and Havertown, Pa., 2020, $34.95

Decades ago this reviewer worked at a British mill that employed many Polish ex-servicemen. Captured by the Russians in 1939, they had been sent via Iran in 1942 to serve in North Africa and Italy, later refusing to return home to communist postwar Poland. One day a Polish co-worker asked whether I’d heard about the wartime Katyn massacre. I had not. Then, with tears in his eyes, he recounted how one of his friends, a cadet officer around my age, had been murdered alongside thousands of other officers.

In what has been described as a crime without parallel the Soviets slaughtered some 22,000 Polish military officers—from ensigns to generals—in April and May 1940. Loved ones simply stopped receiving letters, while anything sent to the missing men was returned as undeliverable. It was later revealed that in the days prior to their murders most of the men had been rounded up amid the vast forests near Katyn, just west of Smolensk.

It was in that region in January 1943 that a German officer noted a wolf frantically digging in the snow close to a birch cross. As the snow melted, two peasants and a railway worker, whose father had been shot by the NKVD (the Soviet secret police), led German military police troops to the same spot. Exploratory digging revealed scores of corpses in Polish uniforms. (Coincidentally, Rudolf-Christoph von Gersdorff, the officer who reported the discovery to Berlin, had escaped Gestapo detection after having participated in a failed attempt to assassinate Hitler at an exhibition of captured Soviet weapons.)

By mid-June digging parties had located eight graves containing 4,143 corpses. Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, a notorious liar and manipulator, for once told the truth as he trumpeted the discovery in hopes of driving a wedge between the Allies.

Meanwhile, in secret dispatches to Franklin D. Roosevelt, Joseph Stalin blamed the Germans for the massacre and complained that the Polish government in exile in London had adopted a “hostile attitude” to the Soviet Union. American intelligence sources subsequently confirmed Katyn as a Soviet war crime in eight separate reports, but presumably for reasons of political expedience and Allied wartime “solidarity” the Roosevelt administration dismissed the reports and buried all relevant records.

Author Thomas Urban succinctly guides the reader through the multiple investigations, as well as the numerous conflicting claims and counterclaims as to who was responsible for the massacre. The book’s epilogue draws attention to several mysterious—and still unsolved—deaths across the years of people with connections to the investigations. Urban also notes that the location of the 7,305 other murdered Polish officers remains known only to those with access to secret NKVD archives. Their fate should never be forgotten.

—David Saunders

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.