The debate over the role of women in the military still continues today. Should women be allowed to serve in the front line? Are some of them really natural born killers?

The debate over the role of women in the military still continues today. Should women be allowed to serve in the front line? Are some of them really natural born killers?

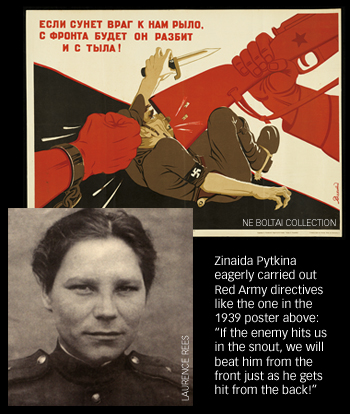

Well, there is no doubt in my mind about the answers to these questions after meeting an extraordinary woman named Zinaida Pytkina. In 1943, as an officer in the Soviet counterintelligence service—known as SMERSH, or “Death to Spies” in English—she shot a young German major after his interrogation. “My hand didn’t tremble when I killed him,” she said. “The Germans didn’t ask us to spare them. They knew they were guilty, and I was angry. I was seeing an enemy, and my father, and uncles, mother and brothers died because of them.” She said that she felt “joy” as she pulled the trigger and saw his body fall backward into his freshly dug grave. Immediately afterward, she said, “I was pleased. I had fulfilled my task. I went into the office and had a drink.”

Though she was in her late 70s when I met her in her ramshackle house in Volgograd (today’s name for Stalingrad), Pytkina was still hard and forthright. Her stare never left me as I talked to her. As she spoke I remembered a serving officer in the FSB—the Soviet national security agency previously known as the KGB— whom I had met earlier on that same trip to Russia. When I had asked him to describe his job, he said that he “solved people’s problems for them.” And now, when asked to describe what her mission had been during the war, Pytkina answered simply that her “mission was to fulfill all the orders of my commanders.” As a result, she said, she and her comrades did “whatever we were told.”

She described how captured German soldiers were tortured during interrogation—or, as she put it in the euphemistic language of SMERSH, treated “gently.” If they didn’t talk, then a “specialist” was brought in to give them a “wash”—the code word for a beating. The majority of the Germans would “sing,” she said, as “no one wants to die.” She didn’t torture the prisoners herself, nor was she allowed to go on a “reconnaissance mission” and crawl up to the German front line to capture a prisoner and bring him back for interrogation. But she relished the chance to kill this young German officer when she was told by her boss to go and

“sort him out.”

“If they had brought a dozen of them my hand wouldn’t have trembled to shoot them all,” Pytkina said. “He had to be destroyed—the same as they treated us, we had to treat them the same way…. At that time if they had lined up all those Germans I would have shot them all down, because so many Russian soldiers lost their lives at the age of 18, 19, or 20, who hadn’t lived, who had to go and fight against the Germans just be-cause they wanted more land…. As a member of the Communist Party, in front of me I saw a man who could have killed my relatives. I would have cut him up if I had been asked.”

I was astonished at the utter ruthlessness that lay within Zinaida Pytkina. “I understand the interest in how a woman can kill a man,” she said. “I wouldn’t do it now. Well, I would do it only if there was a war, and if I saw once more what I had seen during that war, then I would probably do it again.”

I was astonished at the utter ruthlessness that lay within Zinaida Pytkina. “I understand the interest in how a woman can kill a man,” she said. “I wouldn’t do it now. Well, I would do it only if there was a war, and if I saw once more what I had seen during that war, then I would probably do it again.”

She ended the interview with words that stayed with me for a long time after, mixing her capacity to kill with her femininity. “People like him had killed many Russian soldiers,” she said, talking of the young German she had shot. “Should I have kissed him for that?”