“The histories most of our students learn by rote focus, [is] on conflicts battle by battle and name great generals and politicians, but frequently omit those who saved lives by force of will,” writes Jane Shlensky. “Chiune (Sempo) Sugihara [is] one such person of conscience…”

Dubbed “a Japanese Schindler,” after Oskar Schindler, the German factory owner who saved the lives of 1,200 Jews during World War II, the Japanese diplomat is credited with saving the lives of as many as 6,000 Jewish men, women, and children prior to 1941.

Today, according to the Washington Post, “descendants of those with Sugihara visas number between 40,000 and 100,000.”

As a diplomat who spoke fluent Russian, Sugihara was sent to the Lithuanian city of Kaunas (formerly Kovno) in November 1939 to monitor and provide the Japanese with intelligence on German and Soviet troop movements throughout the Baltic region during the Phoney War.

Following the occupation of Lithuania by Soviet forces in June of 1940 and as the situation in Western Europe began to deteriorate, Sugihara recognized that the avenue of escape for Jewish refugees via the west was all but sealed and the eastern route through the Soviet Union to Japan was rapidly closing.

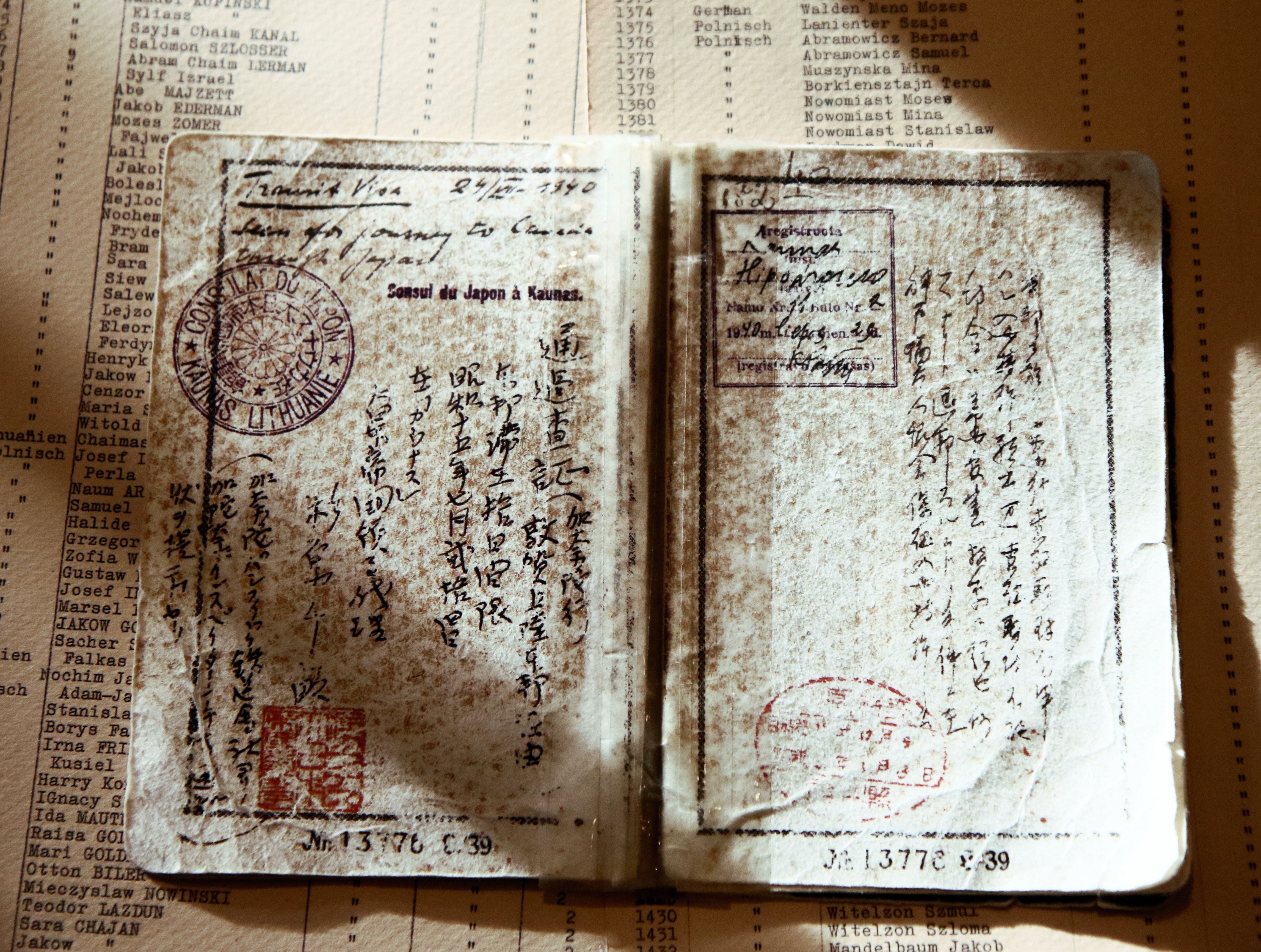

According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, when refugees came to the diplomat with bogus visas for Curacao and other Dutch possessions in America, Sugihara felt a duty to facilitate their escape from war-torn Europe.

Sugihara’s wife, Yukiko, later recalled in an interview with the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation:

At the beginning there were about 200 maybe 300 people. They stood there from morning till night, waiting for an answer. They also stood like this the following day and the day after. They stood all the time. And their small children together with them. People who had escaped from Poland, a place dangerous for them, and together with their children walking day and night, reached Kaunas and the Japanese Consulate asking for visas. They had risked their lives in order to reach this place, their bodies exhausted, their clothes torn and their faces tired. I would see them from my window, when they saw me looking at them, they would put their hands together (as if praying… We did not know what to do… We could not sleep at night… In addition to that, I had a baby, we had three young children. If my husband issues the visas contrary to the Foreign Office instructions, then when we return to Japan, my husband would for sure lose his job… We were thinking and thinking what to do, and the representatives of the refugees begged and begged “please give us the visas.”

Without clear instructions from Tokyo, Sugihara began writing visas — reportedly spending 20 hours a day for a month issuing documents for any Jew who showed up to his office.

One recipient of Sugihara’s altruism, Lucille Szepsenwol Camhi, told the Holocaust Memorial Museum:

“He asked us where our parents were. We told him. My father was not living. My mother has no papers. And he looked very sympathetic at us and he just stamped, gave us the visa right there on the spot.”

Camhi recalled that she and her sister began to hysterically cry, “And he just raised his hand, like saying, ‘It’s okay.’ And that’s it.”

After issuing nearly 2,000 visas, Sugihara was cabled by Tokyo instructing him to desist in such actions unless the refugees had “finished their procedure for their entry visas and also they must possess the travel money or the money that they need during their stay in Japan. Otherwise, you should not give them the transit visa.”

Despite the warning, the diplomat continued in his work. Transferred to Prague in early September 1940, Sugihara issued the last few visas at a hotel just before his departure.

As the Soviets marched through Eastern Europe in 1944, Sugihara and his family were captured and held as prisoners of war in relatively benign conditions for more than two years.

Upon returning home in 1947 the diplomat was forced out of the Japanese Foreign Ministry. According to his son Nobuki, Sugihara was told by a superior officer, “You know what you did. Now you need to leave the ministry.”

Holding odd jobs and later becoming an office manager for a trading company, Sugihara and his deeds lived in relative obscurity until he was tracked down by a visa recipient in 1968.

“He assumed a few people, maybe a few dozen, had actually used the visas to escape,” Nobuki told The Times of Israel in 2019. “He truly did not realize the magnitude of his actions until much, much later in life.”

Shortly before his death in 1986, Yad Vashem in Israel honored Sugihara with the Righteous Among the Nations title, an award honoring non-Jews who not only saved Jewish people, but risked their lives in doing so during the Holocaust.

Today, according to the Washington Post, “descendants of those with Sugihara visas number between 40,000 and 100,000.”