Damian Shiels is an archeologist, historian and author living in Midleton, County Cork, Ireland. As Operations Manager for Rubicon Heritage Services (formerly Headland Archaeology Ireland) he has managed several high-profile projects including the Irish Battlefields Project. Formerly, he was on the curatorial staff at the National Museum of Ireland. His recent book is The Irish in the American Civil War, which he hopes will raise awareness in Ireland of the Irish experience in that conflict and take the story beyond the battlefields with family stories after 1865. He took time out for an exclusive HistoryNet interview with HN‘s senior editor, Gerald D. Swick, while preparing for a presentation, “Patrick Cleburne at the Battle of Franklin,” which Shiels will deliver in Franklin, Tennessee, during the 150th anniversary observance of that costly battle.

Gerald D. Swick: Your author biography says you are an archeologist specializing in conflict archeology. What is conflict archeology?

Damian Shiels: Conflict Archaeology essentially examines the material culture of past conflict. This can encompass a wide range of sites, from actual battlefields to training grounds to military buildings and beyond. I spend a lot of time trying to map Irish battlefield sites from the medieval, historical and modern periods. Accurately locating, plotting and analyzing battlefield finds can teach us a huge amount about these events; the United States has led the way in this, particularly through work at locations such as the Little Bighorn. I also carry out quite a bit of analysis on military artifacts from 16th- and 17th-century battle and siege sites. The most recent conflict-related work I have been doing has been looking at mapping the landscape of guerrilla war during the Irish War of Independence (1919-21) and also examining the conflict landscape of World War One in Ireland—sites such as practice trenches, military hospitals and factories that produced supplies for the Front.

Damian Shiels: Conflict Archaeology essentially examines the material culture of past conflict. This can encompass a wide range of sites, from actual battlefields to training grounds to military buildings and beyond. I spend a lot of time trying to map Irish battlefield sites from the medieval, historical and modern periods. Accurately locating, plotting and analyzing battlefield finds can teach us a huge amount about these events; the United States has led the way in this, particularly through work at locations such as the Little Bighorn. I also carry out quite a bit of analysis on military artifacts from 16th- and 17th-century battle and siege sites. The most recent conflict-related work I have been doing has been looking at mapping the landscape of guerrilla war during the Irish War of Independence (1919-21) and also examining the conflict landscape of World War One in Ireland—sites such as practice trenches, military hospitals and factories that produced supplies for the Front.

GDS: The Irish in the American Civil War says some 200,000 Irish men and women were involved in various ways with the war, including Jennie Hodgers who passed herself off as a man and served with the 95th Illinois. The Irish had been widely discriminated against in America during the great migration caused by the potato famine in the 1840s and ’50s. What are some of the reasons so many chose to fight for one side or the other in their new land?

DS: Irish emigration had been on the rise before The Great Famine, but it was that catastrophe that really tipped the scales in terms of the numbers of Irish in the United States. By 1860 there were 1.6 million people who had been born in Ireland living in America—25% of the entire population of New York alone. This does not include the hundreds of thousands more who had been born in the U.S. to Irish parents and were also seen (and who saw themselves) as part of the Irish-American community. The vast increase in the number of largely poor, Catholic, emigrants was something that alarmed many in American society, and led to the rise of parties like the Know Nothings (officially named the American Party). The vast majority of Irish-born fought for the North (perhaps about 180,000), because they were concentrated in the major cities like New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Cincinnati and Chicago. In contrast, the much smaller Irish population in the South meant that only around 20,000 fought in Confederate gray, although this represented a high percentage of the overall Irish population. It is no surprise that Louisiana boasted the most Irish-men, as New Orleans was the major emigrant port of the South.

In terms of motivation, in the North many of the Irish felt a strong desire to preserve the Union, much as their native-born counterparts did. We also see where people lived being a major factor—for example, Patrick Cleburne made clear that he was going to war on behalf of Arkansas, which was his (adopted) home. Even early in the war finance was a major consideration for those on both sides. Many Irish worked as laborers, which was a form of employment that could be erratic and seasonal; the army offered a steady wage. Of course, there were myriad reasons as to why Irishmen chose to fight. Other examples include those who wanted to gain military experience in the hope of someday using those skills to free Ireland from British rule, and those influenced by Irish propagandists on both sides who tried to harness anti-British feeling by equating the North or South (depending on who they supported) with Britain.

In terms of motivation, in the North many of the Irish felt a strong desire to preserve the Union, much as their native-born counterparts did. We also see where people lived being a major factor—for example, Patrick Cleburne made clear that he was going to war on behalf of Arkansas, which was his (adopted) home. Even early in the war finance was a major consideration for those on both sides. Many Irish worked as laborers, which was a form of employment that could be erratic and seasonal; the army offered a steady wage. Of course, there were myriad reasons as to why Irishmen chose to fight. Other examples include those who wanted to gain military experience in the hope of someday using those skills to free Ireland from British rule, and those influenced by Irish propagandists on both sides who tried to harness anti-British feeling by equating the North or South (depending on who they supported) with Britain.

GDS: In your research, have you found any significant differences in the experiences of Irish immigrants in the North and those who settled in the South?

DS: The major difference is one of scale, given the disparity in numbers between those Irish who fought for the North as opposed to the South. The Irish could be found throughout the armies of both sides, but whereas there were quite a number of ethnic Irish “green-flag” regiments in the Union, there was only one at regimental level in the South. The majority of ethnic-Irish units in the Confederate forces were found at company level. One major difference is that the Irish of the South experienced defeat. Recent analysis by Dr. David Gleeson (see The Green and the Gray: The Irish in the Confederate States of America, UNC Press) has shown that while many Southern Irish went willingly to war—and often fought extremely bravely—they were perhaps somewhat quicker to accept defeat than many of their native-born Southern comrades, suggesting they were not always as invested in the struggle. This changed in the post-war period when the Irish became heavily involved with the Lost Cause. It is interesting to consider how the Irish in the North would have reacted if defeat loomed, but certainly as the war dragged on their enthusiasm also waned. The casualties inflicted on Northern ethnic units in 1862, together with the Emancipation Proclamation, led to growing Irish-American disillusionment with the conflict, culminating in the New York Draft Riots of July 1863.

GDS: Probably the best known of the Irish units in the Civil War was New York’s Irish Brigade and their first commander, Thomas Francis Meagher from Waterford, Ireland. What were some other Irish units that distinguished themselves in the war?

GDS: Probably the best known of the Irish units in the Civil War was New York’s Irish Brigade and their first commander, Thomas Francis Meagher from Waterford, Ireland. What were some other Irish units that distinguished themselves in the war?

DS: The Irish Brigade are certainly the most famous Irish unit of the war. Indeed their fame is so great that I think they often overshadow the wider Irish story of service, both in other ethnic units and in “non-Irish” regiments. The only other brigade-level Irish formation was Corcoran’s Irish Legion, composed of New York regiments; they had many members who were staunch Fenians and were fiercely loyal to their commander, Michael Corcoran. They suffered hugely during the 1864 Overland Campaign. There were many other Union Irish regiments, like the 69th Pennsylvania which helped to turn back the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble assault at Gettysburg, and the 9th Massachusetts, which suffered the highest casualties of any Union regiment at Gaines’ Mill. The list goes on in the Northern armies: the 10th Ohio, 9th Connecticut, 35th Indiana, 23rd Illinois and 90th Illinois were just some who were regarded as largely ethnic Irish. In contrast the only full “green flag” regiment in the South was the 10th Tennessee, although a number of Southern regiments had either large Irish contingents or ethnic-Irish companies in their ranks, such as the 6th Louisiana and the 5th Confederate (which contained a large number of Irish from around Memphis).

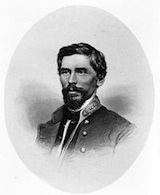

GDS: In a few days (Nov. 14, 2014), you’re going to give a presentation titled “Patrick Cleburne at the Battle of Franklin,” as part of the observance of the 150th anniversary of the battle, in Franklin, Tennessee. For those not overly familiar with his story, Cleburne—often called the Stonewall Jackson of the Western Theater— joined a unit called the Yell Rifles in January 1861, even before the war began. He entered as a private, but by December 1862 he was a Confederate major general. What factors do you attribute to his rapid rise?

DS: Patrick Cleburne’s life experiences and driven personality forged him into a leader of men. Prior to the Civil War he had some military experience, via the British Army, but he seems to have begun to develop his attributes as a leader after his arrival in the United States, particularly during his time in Helena, Arkansas. Cleburne had seen failure up close in Ireland—it had been a failed Apothecaries’ Hall exam in Dublin that had led to him enlisting in the British Army. From virtually the moment he arrived in the United States, he seemed to be someone who was determined not to fail again. This determination was complimented by the fact that he was a quick learner, something he also demonstrated in antebellum Helena in spheres such as business, politics and the law. He took these attributes into his role as a combat leader, where he continued to demonstrate an ability to build upon past experience. Added to this, Cleburne had a personality that many people liked, and he was utterly committed to the society that had given him everything in Arkansas. As the war progressed, the men under his command became more and more confident in their commander’s (and their own) ability—a recognition shared by many Union soldiers when they found themselves facing the distinctive banners of Cleburne’s Division.

GDS: He also made a very controversial proposal to arm slaves to fight for the Confederacy in exchange for their freedom and that of their families. Would you talk a bit about Cleburne’s proposition and about the various attitudes of Irish immigrants toward American slaves and slavery?

DS: Cleburne made his proposal to arm the slaves on January 2nd, 1864. He did it in the context of a period of reversals for Confederate arms, and with the conviction that unless the South could do something to match the manpower resources of the North they faced defeat. He brought his proposal to the attention of the commander of the Army of Tennessee Joseph E. Johnston and other generals at a meeting in Dalton, Georgia. Although some agreed with him, others were horrified. Men such as William B. Bate and William H.T. Walker condemned the proposal outright. Patton Anderson called it “monstrous” and “revolting to Southern sentiment, Southern pride and Southern honor.” Johnston saw the potentially divisive nature of the proposal and ordered it go no further, but an enraged Walker made sure it was sent to Jefferson Davis. Although there is no direct evidence to confirm it, it has been suggested that Cleburne’s failure to achieve corps command in 1864 was as a result of his proposal. We often forget that Patrick Cleburne spent more of his life in Ireland than in the United States. His proposal demonstrates a number of things about his character: his determination to do what he perceived as right for his adopted home, no matter the personal consequences; his directness; and ultimately it illustrated that he did not fully understand Southern society. In the proposal he made the following assumption: “As between the loss of independence and the loss of slavery, we assume that every patriot will freely give up the latter—give up the negro slave rather than be a slave himself.” Clearly, as the reaction by some generals to the proposal highlighted, this was not the case. The proposal was ordered suppressed, and we only know about it because of the discovery of a copy years after the war.

DS: Cleburne made his proposal to arm the slaves on January 2nd, 1864. He did it in the context of a period of reversals for Confederate arms, and with the conviction that unless the South could do something to match the manpower resources of the North they faced defeat. He brought his proposal to the attention of the commander of the Army of Tennessee Joseph E. Johnston and other generals at a meeting in Dalton, Georgia. Although some agreed with him, others were horrified. Men such as William B. Bate and William H.T. Walker condemned the proposal outright. Patton Anderson called it “monstrous” and “revolting to Southern sentiment, Southern pride and Southern honor.” Johnston saw the potentially divisive nature of the proposal and ordered it go no further, but an enraged Walker made sure it was sent to Jefferson Davis. Although there is no direct evidence to confirm it, it has been suggested that Cleburne’s failure to achieve corps command in 1864 was as a result of his proposal. We often forget that Patrick Cleburne spent more of his life in Ireland than in the United States. His proposal demonstrates a number of things about his character: his determination to do what he perceived as right for his adopted home, no matter the personal consequences; his directness; and ultimately it illustrated that he did not fully understand Southern society. In the proposal he made the following assumption: “As between the loss of independence and the loss of slavery, we assume that every patriot will freely give up the latter—give up the negro slave rather than be a slave himself.” Clearly, as the reaction by some generals to the proposal highlighted, this was not the case. The proposal was ordered suppressed, and we only know about it because of the discovery of a copy years after the war.

It is important to understand that Cleburne made the proposal on military grounds; history does not record his personal views on the institution on slavery, although he was almost certainly fully supportive of it. The Irishman made the proposal as he wanted to do all he could in the service of his Arkansas home and the Confederacy. Somewhat ironically, although in 1864 the proposal undoubtedly had a negative impact on Cleburne in the eyes of some contemporaries, today it is one of the central reasons for Cleburne’s popularity. As slavery has become more widely accepted as the root cause of the Civil War, Cleburne’s proposal combined with his prowess as one of the conflict’s leading fighting generals has seen his stock rise. An example of this was his position as runner-up in the Museum of the Confederacy’s “Person of the Year: 1864” symposium held last February, which was decided by audience vote following talks on each of the candidates by noted scholars. This saw him garner more votes than Lincoln, Lee and Grant (Sherman came out on top).

GDS: One last question about Patrick Cleburne. Most Americans pronounce his last name CLAY-burne, but I’ve read that in Ireland the family name is pronounced CLEE-burne, which is also the pronunciation used for the town in Texas that some of the general’s soldiers named in his honor. What is the correct pronunciation of his last name?

DS: Cleburne is not that common a name in Ireland, and many people would pronounce it CLEE-burne (Indeed, as I used to do!) but the derivation of the name suggests that CLAY-burne is the correct and intended pronunciation. I think there is little doubt that during his lifetime both forms were commonly used for him (as they were by the troops under his command).

GDS: Thank you for taking time to do this interview with HistoryNet. Is there anything you’d like to add in closing?

DS: Many thanks for having me! I am greatly looking forward to the events surrounding the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Franklin and having the great honor of talking about so notable an Irish emigrant at the place where he died. Hopefully I will meet some readers there!

Gerald D. Swick’s articles about the Civil War include “‘Atlanta is Gone'” and “Ballots and bullets,” in the September and November 2014 issues of America’s Civil War magazine, respectively.