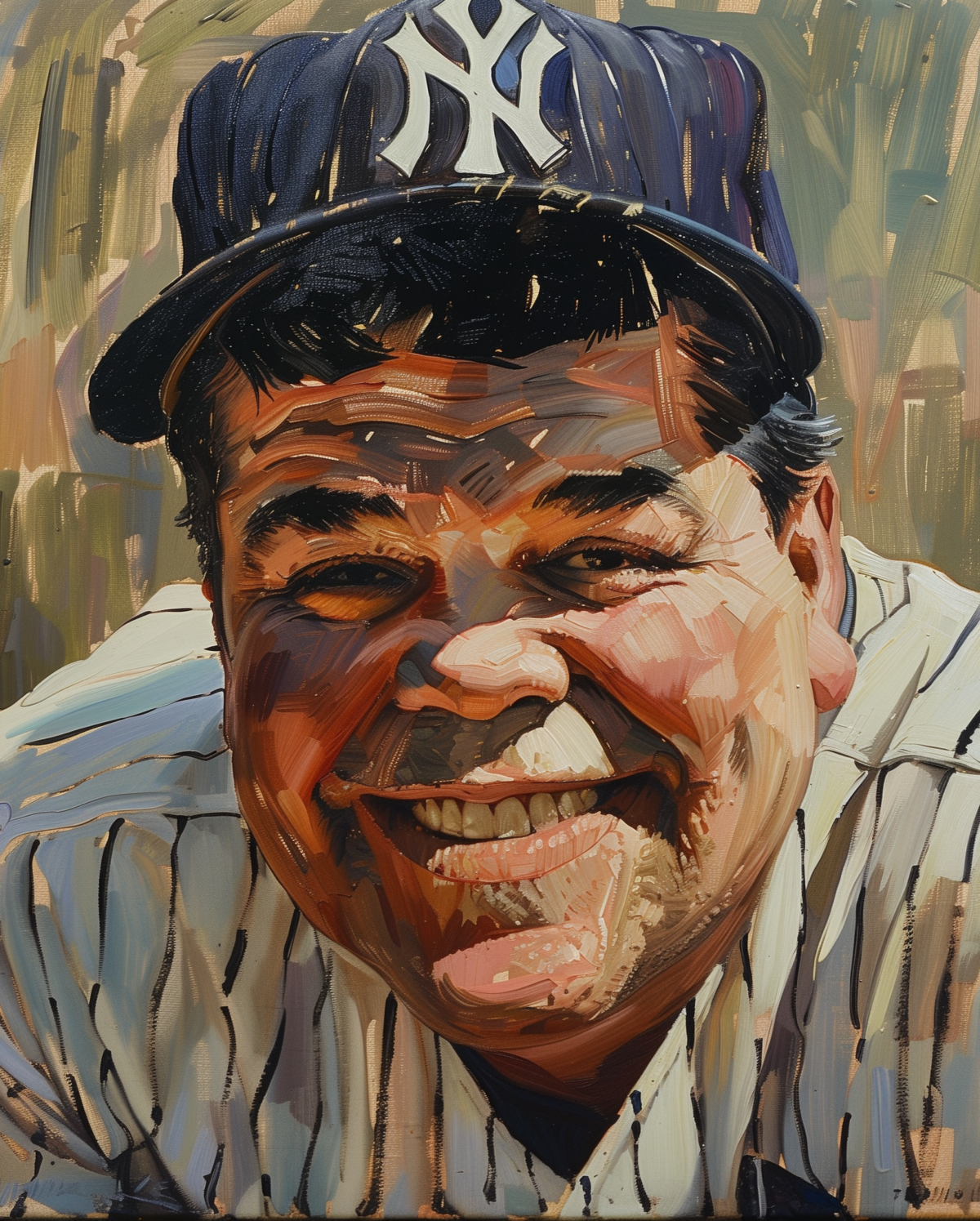

Babe Ruth, baseball’s Sultan of Swat, was renowned for living large. He openly gambled, drank during Prohibition, ate to excess, cheated on his wife, engaged in public brawls, caroused with gangsters and defied authority to the point of dangling his New York Yankees manager, Miller Huggins, upside down from the platform of a moving train. America forgave him all, because his boisterous personality was so reflective of the country’s own in the Jazz Age, and also because he was adored as the man who saved baseball after the 1919 Black Sox scandal in which eight Chicago players conspired to fix the World Series. Ruth was universally seen as the man whose powerful swing launched the game into a new era of glory.

Seventy-five years ago this spring, Ruth headed the charter class of players elected by sportswriters to the Baseball Hall of Fame. Four years would pass before a permanent shrine and museum to honor baseball’s all-time greats would open in Cooperstown, N.Y. But Ruth and his four cohorts in the 1936 Hall of Fame class—Christy Mathewson, Honus Wagner, Walter Johnson and Ty Cobb—had already taken their places in the larger historical pantheon of national heroes. During the early 20th century and especially the Depression years, when so many Americans couldn’t help but feel like losers, the winning ways of men who turned a boy’s game into a Herculean spectacle was both a welcome diversion and a source of great hope. The Babe and his fellow baseball immortals, who are profiled on the pages that follow, were the first bona fide sports superstars, gamers who by their dazzling skills and larger-than-life personalities emerged as legends in their own time.

The charter Hall of Fame class included a feisty orphan, a coal miner’s son, a country bumpkin, a war hero and one irredeemable son of a bitch.

The Bambino

R is for Ruth.

To tell you the truth,

There’s no more to be said,

Just R is for Ruth.

Babe Ruth in his prime was the most popular and most famous man in America, with the possible exception of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. But when he first came on the scene in 1914, baseball was still a fairly quaint enterprise that had emerged as our national pastime because it was democratic at its core: a rollicking team sport that nearly anyone could play—and nearly everyone did—in schoolyards, small town greens, city streets and vacant lots. Likewise anyone who played the game could at least fantasize about being a star.

Christened George Herman, Ruth emerged from nowhere. When he was growing up in Baltimore, his saloonkeeper parents left him at age 7 in the custody of Catholic missionaries running a boys school for orphans and delinquents. His exploits on the ballfield attracted the attention of Jack Dunn, owner of the then minor league Baltimore Orioles, who adopted him at age 19 so he could play for the team. Nicknamed Jack’s latest “babe” by his teammates, Ruth might have become baseball’s greatest lefthanded pitcher. He pitched nine shutouts for the Boston Red Sox in 1916, a regular season record for an American League lefthander that would not be broken until 1978, and during the 1916 and 1918 World Series he ran up a consecutive 292/3 score-lessinnings streak that stood until 1961. But in two subsequent seasons with the Red Sox and then 14 glorious seasons with the New York Yankees, he migrated to the outfield and became the game’s greatest hitter, leading the major leagues in home runs 12 times.

Ruth became a star during the tail end of what would later be called the “dead ball era,” but the brand of baseball he helped usher in was a high-scoring, big city version of the game that stressed power over speed and finesse. Above all, with one mighty swing of his bat after another, he brought joy to the lives of everyday Americans.

The Flying Dutchman

W is for Wagner,

The bowlegged beauty;

Short [stop] was closed to all traffic

With Honus on duty.

Honus Wagner was the first player to have his name engraved on a Louisville Slugger bat, and no shortstop before or after—not even Cal Ripken or Derek Jeter—has approached his combination of offensive and defensive excellence. The son of proud German immigrants who settled in Pittsburgh, he dropped out of school at 12 to work alongside other members of his family in the coal mines, then followed two of his brothers into professional baseball in 1897. Wagner spent most of his career with his hometown Pittsburgh Pirates and was lionized by local immigrants. He was a hulk of a man, with massive shoulders on a 5-foot-11, 200-pound frame, bowed legs, long arms and gargantuan hands and feet. But his speed and German heritage earned him the nickname “The Flying Deutschman,” which was inevitably altered to the more easily pronounceable “Dutchman.”

Wagner was not only a fantastic fielder who was strong enough to throw a baseball more than 400 feet, but also a flawless base runner and hitter. He regularly led the league in stolen bases and runs batted in, and had the top batting average in the National League a record eight times. During Wagner’s entire 50-plus-year career as a player (he set numerous records as the oldest active player in the league) and as a Pirates and local college coach, not a breath of scandal was whispered about him. In his later years, he ran a well-known sporting goods store and remained a popular figure in Pittsburgh until his death in 1955 at age 81. In 2007, his 1909 American Tobacco card sold for $2.8 million, the highest price ever paid for a baseball trading card.

The Big Train

J is for Johnson

The Big Train in his prime

Was so fast he could throw

Three strikes at a time.

Walter Johnson was a mild-mannered country boy whose gangly presence on the pitching mound and easy windup were deceptive. Before Ty Cobb stepped into the batter’s box to face Johnson for the first time in 1907, he and his fellow Detroit Tigers yelled at Joe Cantillon, the manager of the Washington Nationals: “Get the pitchfork ready. Your hayseed’s on his way back to the barn.” But Cobb and his teammates sang another tune when Johnson sailed one sizzling fastball after another past them. “Every one of us knew we’d met the most powerful arm ever turned loose in a ballpark,” Cobb recalled.

Johnson, who spent much of his childhood on a Kansas farm before his family moved west when he was a teen to try their luck in California oil fields, won a breathtaking 417 games over his 21-year professional career. That total was even more impressive because he spent his entire career with the American League’s worst team, the Washington Nationals/ Senators. Or they would have been the worst had it not been for Johnson, who pitched them into the top half of the American League 11 times. A sidearm fastballer, he was the game’s first real power pitcher. But it was said that hard-nosed batters— such as Cobb, who faced him often—would take advantage of Johnson’s well-known gentle disposition and crowd the plate, knowing that he was reluctant to risk hurting someone with his fearsome fastball. Johnson’s method of pitching, said an opposing manager, was simple: He threw a fastball, and if that didn’t work he threw a faster one.

Sportswriters commonly referred to Johnson as “Sir Walter” because of his unfailing politeness. But the way his fastball relentlessly bore down on hitters reminded Grantland Rice of a powerful locomotive and inspired the nickname “The Big Train.”

Saint Matty

M is for Matty,

Who carried a charm

In the form of an extra

brain in his arm.

Christy Mathewson had already practically achieved sainthood status before he was posthumously inducted in the Baseball Hall of Fame, having been depicted in stained glass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York. Born in Factoryville, Pa. (you can’t make this stuff up), Mathewson was one of the few college-educated early major leaguers; at Bucknell University he was class president, and played football (he was chosen an All-American in 1900) as well as baseball. He was America’s first great baseball hero, and after enlisting in the army in World War I, where he was a captain in the Chemical Warfare Service, he became for millions of Americans an even larger hero. After inhaling mustard gas during a training exercise accident, he developed tuberculosis, which finally killed him in 1925 at the age of 45.

Pitching 17 seasons with the New York Giants and the Cincinnati Reds, Mathewson won 373 games, including 20 or more in 13 seasons and 30 or more four times. Dominating the 1905 World Series, he pitched three complete-game shutouts in just six days. A clean competitor and model teammate, he was so devout that he never pitched on Sunday. Matty wrote several baseball novels that stressed the importance of clean living in achieving success in baseball, and instructional books, such as Pitching in a Pinch, still considered one of the best guides ever.

The Georgia Peach

C is for Cobb,

Who grew spikes and not corn,

And made all the basemen

Wish they weren’t born.

Ty Cobb was the black sheep of baseball’s first family: a fanatic competitor who had slashed many an opponent’s calf with sharpened spikes. But he won an amazing 12 batting titles over 13 seasons, had baseball’s all-time highest batting average (.367, still the record), and held numerous other records that would last for decades, including most career stolen bases, 892. If the Hall of Fame had been a mere popularity contest, Cobb would not have had a chance, but his greatness as a player could not be denied.

Born in Narrows, Ga., and a lifelong brawler on and off the diamond, Cobb was in the words of one sportswriter, “a southern Protestant who hated northerners, Catholics, blacks and apparently anyone who was different from him.” He fought with everyone: opponents, teammates, umpires, groundskeepers, fans, family and passersby. His life off the ballfield was a Southern Gothic, demon-driven tale of violence that included his mother’s killing his father with a shotgun when Ty was 19 (she was acquitted of murder) and Cobb’s whipping his own son when the latter flunked out of Princeton.

Cobb was shrewd with money and, not surprisingly, a tough negotiator. He invested smartly, mostly in Coca-Cola and General Motors, and by the time he died of cancer in 1961, at age 74, he was a multimillionaire. But only four people from organized baseball attended his funeral.

A Perfect Day

Baseball royalty descended on Cooperstown, N.Y., for the Hall of Fame opening and ended up choosing sides in a field of dreams.

The wail of the train whistle that reverberated through the Susquehanna Valley on the morning of June 12, 1939, augured a day like no other in the splendid rural village of Cooperstown, N.Y. The number of people in town that day had swelled to 15,000, three times the normal population, in anticipation of the arrival of the greatest assemblage of baseball players ever seen. The occasion for the celebration was the dedication of baseball’s new Hall of Fame Museum and the induction of the charter 1936 class, as well as three additional classes that had been chosen before the building was completed. Walter Johnson and Honus Wagner were aboard the train, which was packed with baseball luminaries. But when the locomotive came to a stop in the station, the roar that erupted from the crowd was “Babe! Babe! Babe!”

Every barbershop, ice cream parlor, soda fountain and diner in Cooperstown was packed with fans trailing their heroes around, thrusting every kind of object from pennants to scorecards in their faces, begging for a signature. Babe Ruth’s entourage followed him to a barbershop, where he was hoping for a quick shave; finding a line, he waved and departed. The barber later told a visiting writer that he would have put Ruth ahead of his other customers but the Babe did not ask. “To think,” he said with regret, “that I almost shaved Babe Ruth.”

Schools were dismissed at 10:00 a.m. so children could join their parents for a once-in-a-lifetime chance to see in the flesh men who they had previously known only through newsreels and newspaper photos. Traffic on Main Street ground to a halt. Every shop sold commemorative pillows, windshield stickers, centennial postcards and souvenir bats. Red, white and blue bunting adorned the buildings and homes. Families carried picnic basket lunches down to the lakeside and found themselves sitting beside such household names—and future Hall of Famers—as Eddie Collins, Hank Greenberg, Tris Speaker, Lefty Grove and George Sisler.

Ty Cobb arrived late, after a 3,000-mile rail trip from California with his teenage son and daughter, and explained that he’d gotten ill and stopped for medical attention in nearby Utica. Or perhaps his competitive fires still burned and he arrived late to avoid getting upstaged by the Babe. In any case, he put on a smile and shook hands with fans and writers (some of whom he had threatened over the years to kill for what they had written about him) as if he were running for public office.

After a brief tour of the new museum and lunch, a parade led the old and new timers though the village streets to Doubleday Field, where Honus Wagner (Class of ’36) and Eddie Collins (Class of ’39) grabbed a bat to “choose up” sides by the old hand-over-hand method popular in schoolyards. In addition to Ruth, Wagner’s team featured future Hall of Famers Lefty Grove, Joe “Ducky” Medwick, Charley Gehringer and Arky Vaughan. Collins countered with Lloyd Waner, Mel Ott, Hank Greenberg and Dizzy Dean.

The players changed into their uniforms in the gymnasium of the nearby Knox Girls School. As he was putting on his cleats, Ruth found a note in his shoe from Cobb, who did not play that day: “I can beat you any day of the week and twice on Sunday.”

Despite the presence of so many great players, it was not a day for all-star performances. In the account of a former Hall of Fame director, “The game itself was just a clam bake affair with skill and precision tossed to the four winds. Players were there to be seen and have fun. Line-up changes were frequent.” The Babe, already looking old beyond his 44 years (he would die of cancer at age 53), drew mighty applause from the packed-in crowd for simply popping up to the catcher in the fifth inning. The game was called in the seventh inning with Wagner’s team ahead because many of the participants had to catch the day’s last trains out of the village.

The old timers, some wearing their baseball caps, strode from the gym to the station, still signing autographs. Most would never see Cooperstown again. But they would never be forgotten.

Allen Barra writes about sports for the Wall Street Journal. His latest book is Yogi Berra: Eternal Yankee.

Originally published in the April 2011 issue of American History.