Still going strong after 60 years of service, the rock-solid MiG-21 supersonic fighter gained a fearsome reputation despite its lackluster combat record.

While the United States was cranking out Century Series fighters, all spectacular but none particularly effective in the role for which they were intended, the Soviet Union quietly came up with a weapon of enormous capability, performance, economy and longevity: the single-engine, Mach 2 Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 “Fishbed.” It was an airplane that hewed to the classic “perfect is the enemy of good enough” approach. The Americans were trying to create superfighters in small numbers, but the Soviets wanted to fill the sky with thousands of simple, lightweight, reliable jets. After all, that strategy had worked splendidly with the AK-47 rifle.

Fishbed was its randomly chosen NATO identifier. The Soviets hated it, just as they hated Fagot, Faithless, Frogfoot and other Western names for their fighters. The MiG-21 had no official Russian identifier, but its popular handle was Balalaika, after the triangular folk instrument—an obvious reference to the MiG’s delta wing.

The MiG-21 had a long production run—1959 to 1985—and the airplane was thereafter updated and modified by companies in India, Israel and Romania; copied by the Chinese; and simply rebuilt and kept in service so long that even today there are 14 developing countries operating the ancient jet as their first-line fighter. The Fishbed is the most-produced supersonic fighter of all time, with 11,496 manufactured. Its baby brother, the transonic MiG-15, holds the all-time jet record: some 18,000 units.

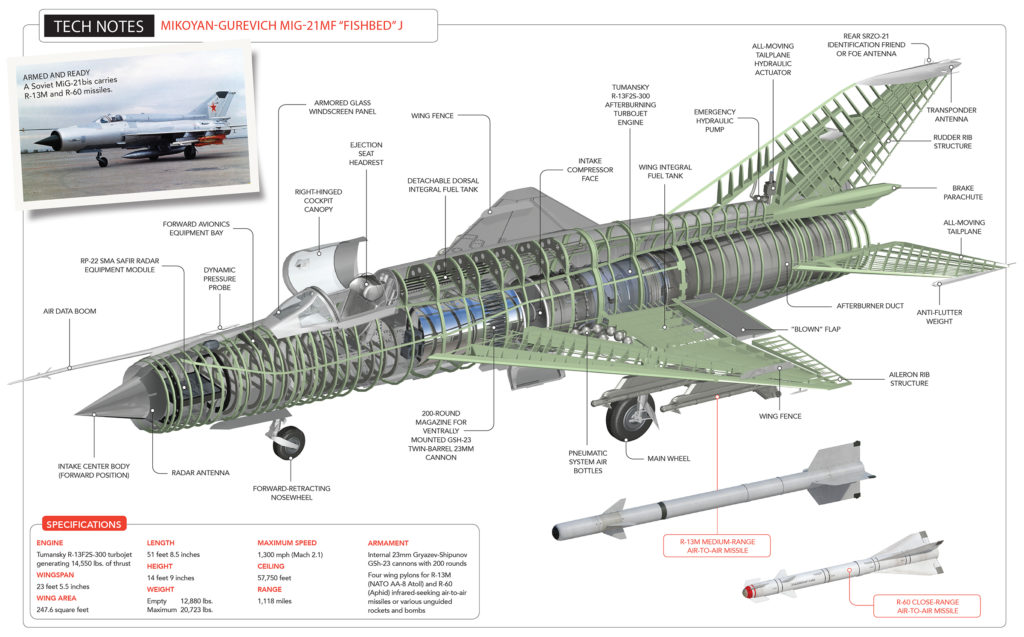

The final Soviet-produced Fishbed was the MiG-21bis, manufactured between 1972 and 1985. This refined model corrected many of the failings of earlier marques. (Bis, Latin for “second,” more broadly means “improved.”) The ultimate MiG modification was the Indian Air Force’s MiG-21-93, which the Indians called the Bison. It had a MiG-29 bubble canopy and wraparound windscreen; far more capable radar; a helmet-mounted weapons sight; and beyond-visual-range, fire-and-forget missile capability. These and other mods created a four-fold increase in the airplane’s capability and brought it up to roughly the level of an early F-16.

The MiG-21 has been called the AK-47 of airplanes. “Rock-solid airframe,” noted a former aviation technician who ground-crewed on one. “Really the thing only needs to be topped off with fluids and it just goes and goes.” When the U.S. Air Force operated MiG-21s as adversary aircraft combat trainers, they found them to be, in the words of one crew chief, “Just like your family car. As long as it’s full of fuel, you pull it out of the garage and start it up.” Maintenance typically consisted of changing the oil, brakes and tires after every 50 sorties. “With a set of Home Depot metric socket wrenches and screwdrivers, you could get a lot of maintenance done on the little jet,” said another crew chief.

Even more important is the fact that a MiG-21bis can be had for $500,000. A secondhand F-16C can cost a small country $15 million.

Yet for all its masterful qualities, the MiG-21 wasn’t an unmitigated success. The Fishbed has flown in some 30 wars, and its combat record is a negative number: More of them have been shot down than have downed opponents. There have only been four MiG-21 aces ever—three North Vietnamese and one Syrian. Much of this has to do with the pilots: Egyptian and Syrian MiG drivers fighting talented Israelis; North Vietnamese against better-trained F-4 crews, if not at first, at least as the Vietnam War progressed; Asian and African air forces out of their depth. Egyptian MiG-21 pilots were so inept during the Six-Day War that one of them shot down another Egyptian MiG…and then was himself shot down by Egyptian antiaircraft fire.

When pilots argue about combat between disparate types—a MiG-21 and a more modern fourth-generation fighter, say—they sometimes bring up the classic “knife fight in a phone booth” between a big guy and a little guy. Once the big guy launches his missiles, he just might find himself trying to dogfight in that phone booth if they miss. And air-to-air missiles did usually miss. Over Vietnam, 91 percent of Sparrows and 82 percent of Sidewinders

fired by F-4s failed to find their mark.

Early in the Vietnam air war, the Phantom-versus-Fishbed battle was a classic case of the phone booth fight. The little MiG was far more nimble and tighter-turning than the big F-4, until American pilots learned to “fight in the vertical.” Rather than dogfighting in tailchases, F-4 pilots used their superior acceleration and thrust to climb vertically, away from the fight, and then to pull over the top and come back down full of altitude and energy.

Second-generation 1950s-’60s Fishbeds have for some time faced third- and fourth-generation jets of undeniably superior capability. The MiG-21 was exported in huge numbers to a wide variety of air forces with varying strengths and skills. In some cases, it was the best jet these countries could afford, and too often they found themselves going to the mat with opponents flying F-14s and F-16s.

The air force for which the Fishbed had been designed, the Soviet Frontal Aviation Branch, ultimately got little use out of its new fighter. During the Soviet war with Afghanistan, the MiG-21 was used solely for ground attack, and one of the few aerial victories earned by a Fishbed occurred in 1973 when an Iranian aircraft strayed into Soviet airspace. The Soviet pilot missed with two missiles and then found himself too close to the target to allow space for his remaining two missiles to arm, so he rammed the interloper. A rather extreme way of dealing with a simple navigation error, particularly since the Russian pilot was killed and the two Iranians—actually a U.S. instructor and his Iranian student—ejected and lived.

The MiG-21 is a tiny thing, a fact belied by what looks like an enormous fuselage in proportion to its highly loaded little delta wings. Park a Fishbed next to an F-4, however, and the Soviet fighter looks like a 4/5th-scale toy. It is little more than 40 percent the empty weight of a Phantom II, with a wingspan 15 feet narrower and a length 11 feet shorter. At comparable combat-loaded gross weights, an F-4 was four times as heavy as a MiG-21. The Fishbed is roughly the size of a Northrop F-5, an airplane that was frequently used as a stand-in for the MiG-21 during dissimilar-types air combat maneuvering (ACM) training. In a head-on engagement, the Fishbed was a mere dot in the sky suspended between two tiny wings, while a fat twin-engine F-4, smoking like a locomotive, announced its presence from two counties away.

But it’s possible the MiG pilot didn’t see it anyway. Squeezed into a narrow cockpit bracketed by the big Tumansky engine’s air ducts, he sat between high canopy rails and an inch-thick, triple-layer composite windscreen obscured by a big ballistic gunsight, head-up display and often a clutter of switch panels and electronics. Vision aft from about 4 to 8 o’clock was nonexistent, and the view down was minimal.

Only the earliest MiG-21s, with bubble canopies and a small dorsal fairing aft of the cockpit, offered adequate vision. The dorsal fairing was soon enlarged and made into a fuel tank, and the canopy was changed to a more vision-restricting design. The initial canopies, hinged to the windscreen at the front, were part of the ejection seat package. They stayed with the seat during punch-out and provided the pilot with a protective shield. The Soviets were longtime ejection seat innovators, but this mechanism proved to be complex and unreliable, so the Fishbed was later provided with a more conventional side-hinged blowoff canopy.

With the best field of view forward and upward through the canopy, some North Vietnamese MiG units used jungle-camouflaged Fishbeds flying down in the weeds, lost to radar in the ground clutter. “Snakes in the grass” was the warning call when they were spotted, but sometimes it was too late. They would approach F-105 Thunderchiefs from below and behind, then climb hard in afterburner, strike from 6 o’clock low and flee for home.

Most MiG-21s were lightly armed: two Atoll heat-seeking missiles and just 30 rounds, a two-second burst, for their single 30mm cannon. Often even this wasn’t needed over Vietnam, though. If a MiG threat could make an F-105 or F-4 punch off its stores, the attack was successful. The North Vietnamese could head home knowing they had forced the enemy to waste time, fuel and ordnance.

Fighter pilot Robin Olds, a 12-victory World War II ace who added four MiG kills in Vietnam, knew just how good a fighter the MiG-21 nonetheless was. “The best flying job in the world was a MiG-21 pilot at Phúc Yên,” Olds once said. “Hell, the way we fought that f—ing war, if I’d been one of them I’d have got 50 of us.”

Olds did spring a major MiG trap, Operation Bolo, that during a single melee in January 1967 shot down five of those best-job-in-the-world pilots—eliminating almost half of North Vietnam’s operational Fishbed fleet. Olds and his squadron mates imitated the speed, altitude, route, formation and radio calls of a strike package of bomb-heavy F-105s. When 16 eager Phúc Yên Fishbeds burst out of the undercast below, they found not vulnerable fighter-bombers but 28 locked-and-loaded Phantoms.

One thing the irascible Olds wouldn’t have enjoyed was that Fishbeds were controlled from the ground. Ground-controlled intercept (GCI) meant that MiG-21 pilots not only took up increasingly fine vectors and altitudes provided to them by radar operators on the ground, but even fired the weapons that the GCI guys ordered them to and pickled their drop tanks on command.

Mikoyan and Gurevich’s design bureau had chosen a single gaping nose air intake for the MiG-21’s engine because of its simplicity and efficiency, but this severely limited the airplane’s ability to carry its own radar. Only a small dish would fit into the airflow-slowing nose cone, and anything that involved searching more than a few miles ahead became the job of observers on the ground linked to huge radar arrays. (That three-position nose cone slid in and out, depending on airspeed, to generate shockwaves that would slow inlet air to a speed the engine could swallow.) MiG-21 onboard radar was famously near-useless.

F-105 fighter-bombers were the Fishbed’s favored target over Vietnam. The Thuds were so fast—up to 700 knots down low—that it required a super-interceptor simply to catch them. When MiG-21s did overhaul them, they ended up shooting down 17 F-105s with no MiG losses to the Thuds.

The Fishbed had one other serious flaw: Designed to climb extremely rapidly to altitude, shoot down a single non-maneuvering bomber and return to base, it carried just enough fuel to fulfill that mission—typically 45 minutes’ worth. Nor could a MiG-21 be dead-sticked to a landing if fuel ran out while near its airbase, since a power-on approach was required. Early MiG-21s had a poorly designed fuel system to boot. A full 175 gallons of fuel remained unusable and created an aft center-of-gravity shift during landing approaches, which killed many inexperienced pilots.

The Fishbed first went to war in 1965, flown by Indian pilots against Pakistanis, though there was no actual air combat. The first-ever MiG-21 victory came the next year, over Vietnam, when a North Vietnamese pilot shot down an American Ryan Firebee surveillance drone—sounds simple, but the Firebee was cruising at 59,000 feet (the MiG-21 actually can intercept at up to 65,000 feet).

It was in the Mideast, however, that the Fishbed would first go into all-out war.

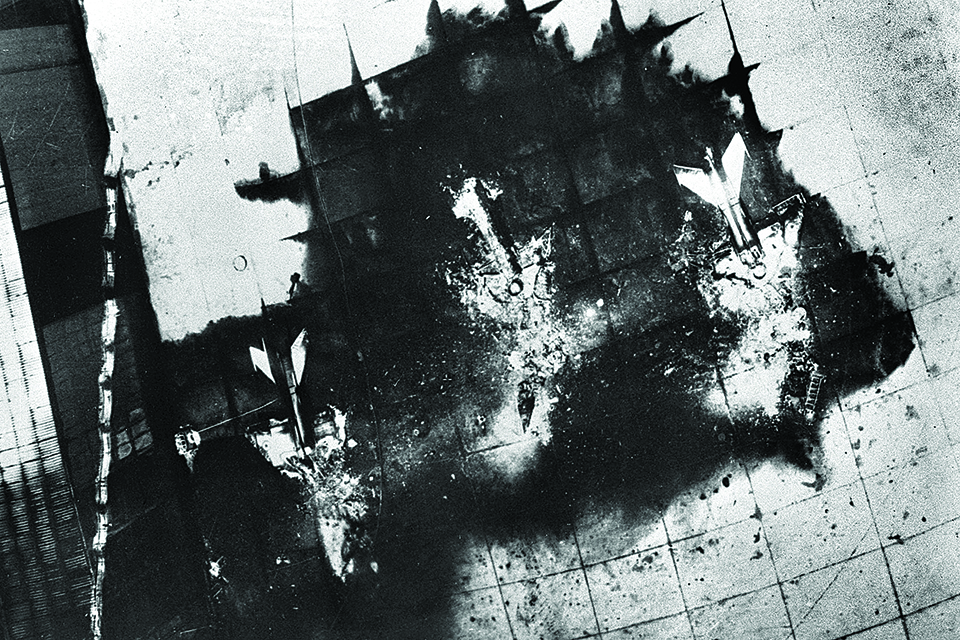

In 1966 Israel was surrounded by MiG-21s. The Soviets had provided client states Egypt, Syria and Iraq with 194 Fishbeds as part of an overwhelming Arab buildup of troops, tanks and aircraft intended to wipe Israel off the map. The Arabs waited just a little too long, though, and early in the morning of June 5, 1967, Israel began the Six-Day War with a preemptive strike that wiped out most of the MiGs and other Arab jets on the ground.

Israel had already decided it needed a MiG of its own to fly and evaluate, so that it could refine the air-to-air tactics of its fleet of delta-wing Mirage IIICJs, which were equivalent to the MiG-21 in many ways. Israel’s Mossad intelligence agency recruited a disgruntled Iraqi MiG pilot to defect with his airplane, in exchange for $300,000 and Israeli citizenship for himself and his family.

The Israel Air Force flew the Iraqi MiG enough to determine that it was a good high-altitude interceptor, was easy to fly and that, against a Mirage, pilot skill would determine the outcome. In other words, bring it on.

The IAF then painted the stolen MiG in a high-visibility color scheme, slapped on Star of David roundels and the appropriately intriguing number “007,” and parked it on a ready ramp prepped to scramble and shoot down Arab MiG-21s flying at altitudes unattainable by the Mirages. The call never came, and in 1968 the airplane was lent to the U.S. for its own testing and evaluation. It can still be seen at the IAF Museum in Hatzerim.

A decade later, the U.S. Air Force would become far more seriously involved with Fishbeds when it established the 4477th Test and Evaluation Flight, soon to officially become a squadron, as part of the top-secret Operation Constant Peg. At one point, Constant Peg was operating 17 MiG-21s out of a secret airfield near Tonopah, Nev., in the mystery-shrouded Area 51. The airplanes were officially YF-110s, since the Air Force now owned them. They had been acquired from scrapyards and from foreign air forces that needed cash, dug out of swamps where they’d been left to rot, given as gifts by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and even simply bought new from the Chinese, which had manufactured them as Shenyang F-7Bs.

Shenyang F-7s—today designated Chengdu J-7s—are invariably referred to as “license-built MiGs,” which is not true. China and the Soviet Union had initially tried to strike a licensing deal, but the arrangement came apart as Sino-Soviet relations soured. The Chinese ended up disassembling a MiG-21 and reverse-engineering it for production. They even tried working with Grumman during the process, but the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre ended that arrangement. The F-7s were the very last production MiG-21s, and about 2,400 were manufactured, some as recently as 2013. The Chinese MiGs corrected the original version’s faulty fuel tank design, among other things.

Constant Peg pilots griped that the arcane Eastern Bloc instrumentation read out airspeed in “kilometers per fortnight.” They also had to re-learn how to taxi: The MiGs had brakes powered by a compressed-air tank and applied by differential rudder pedal input plus a bicycle brake handgrip on the joystick. If you used up too much air weaving your way out to takeoff, there wouldn’t be enough left for braking on landing, since the MiG carried no compressor. The only recourse was a braking parachute plus a frequently employed catch-net at the end of the Tonopah runway.

Constant Peg’s mission was to train American pilots to fight against a variety of Soviet aircraft, particularly the MiG-21 and -23. The initial ACM schooling involved simply letting a pilot see a MiG-21 in the air, up close. For many of them, it was like sitting at a stoplight waiting for an informal drag race and watching a Formula 1 car pull up in the next lane. The Fishbed was still that fearsome an opponent.

Constant Peg ended in 1989 after generating more than 15,000 MiG-21 and -23 sorties against opposing fighter pilots, though the program wasn’t declassified until 2006. At least five formerly Indonesian MiG-21s became gate guardians or went to museums or display areas, including the aggressor-aircraft park at Nellis Air Force Base, in Las Vegas, known as the “Petting Zoo.” One 4477th technician recalled that a 40-foot-deep hole was dug in the desert near Tonopah and filled with the F-7s bought from China as well as spare wings and engines.

The MiG-21 will soon end its operational career, after at least 60, perhaps even 65 years. Even today, Syria’s air force is flying them, dropping homemade propane tank bombs on rebels and ISIS. There is no possibility of the Fishbed approaching the Boeing B-52’s near-century of service when the Stratofortress stands down in 2050, but those ancient MiGs will likely be flying in the hands of warbird enthusiasts long after the last B-52 shuts down forever.

Contributing editor Stephan Wilkinson recommends for further reading: Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21, by Alexander Mladenov; MiG 21 Fishbed, by Gerard Paloque; and America’s Secret MiG Squadron, by Col. (Ret.) Gaillard R. Peck Jr.

This feature originally appeared in the May 2019 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!