IN LATE OCTOBER 1944, the U.S. First Army set up its winter headquarters in the Belgian town of Spa. A flourishing resort since the 1500s—the German travel-guide publisher Karl Baedeker had called it “the oldest European watering-place of any importance”—Spa reached its zenith in the 18th century with visits by Peter the Great and other potentates keen to promenade beneath the elms or to marinate in the 16 mineral springs infused with iron and carbonic acid. The town declined after the French Revolution, then revived itself, as such towns do—in Spa’s case, by peddling varnished woodware and a liqueur known as Elixir de Spa. Here the Imperial German Army had placed its field headquarters during the last weeks of World War I: It was in the Grand Hôtel Britannique on the Rue de la Sauvenière that Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg concluded the cause was lost. The last of the Hohenzollerns to wear the crown, Kaiser Wilhelm II, arrived here from Berlin in October 1918, to fantasize about unleashing the army on his own rebellious volk; instead he chose abdication and exile in the Netherlands.

But in 1944 GIs hauled the roulette wheels and chemin-de-fer tables from beneath the crystal chandeliers in the casino on the Rue Royale, replacing them with field desks and triple bunks. “We’ll take the ‘hit’ out of Hitler,” they sang. Tests by army engineers confirmed that every one of the city’s 11 drinking water sources was polluted, but a decent black market meal could be had at the Hôtel de Portugal—horsemeat with mushroom caps seemed to be a regional specialty in these straitened times. As for the thirsty, each general in First Army received a monthly consignment of a case of gin and half cases of scotch and bourbon; lesser officers combined their allotments in a nightly ritual to make 12 quarts of martinis for the Hôtel Britannique mess, a grand ballroom with mirrors on three walls and exquisite windows filling the fourth. Headquarters generals also requisitioned the hilltop mansion of a Liège steel magnate as their bivouac; Belgian guests were occasionally invited to movie screenings in a nearby school, where soldiers tried to explain in broken French the nuances of Gaslight and A Guy Named Joe. The New York Times war correspondent Drew Middleton reported that fleeing German troops had left behind in an Italian restaurant a recording of “Lili Marlene”; GIs played the disc incessantly while assuring skeptical Belgians that “the song had been taken prisoner…and could no longer be considered German.” Almost hourly, the clatter of a V-1 bound for the key Belgian shipping port of Antwerp from one of the launch sites in the Reich could be heard in the heavens above Spa.

The First Army commander, Lieutenant General Courtney H. Hodges, moved his office into Hindenburg’s old Britannique suite and settled in to ponder how to wage a late autumn campaign in northern Europe. Hodges was an old-school soldier: He had flunked out of West Point—undone by plebe geometry—and risen through the ranks after enlisting as a private in 1905. The son of a newspaper publisher from southern Georgia, he was of average height but so erect that he appeared taller, with a domed forehead and prominent ears. Army records described the color of his close-set eyes as “#10 blue.”

“God gave him a face that always looked pessimistic,” Dwight Eisenhower once observed, and even Hodges complained that a portrait commissioned by Life in early September made him appear “a little too sad.”

A crack shot and big game hunter—caribou and moose in Canada, elephants and tigers in Indochina—Hodges had earned two Purple Heart citations after being gassed in World War I but deemed them excessively “sissy” and tore them up. He smoked Old Golds in a long holder, favored bourbon and Dubonnet on ice with a dash of bitters, and messed formally every night, in jacket, necktie, and combat boots. He had been seen weeping by the road as trucks passed carrying wounded soldiers from the front. “I wish everybody could see them,” he said in his soft drawl. One division commander said of him: “Unexcitable. A killer. A gentleman.” A reporter wrote that even in battle “he sounds like a Georgia farmer leaning on the fence, discussing his crops.” General Omar Bradley, who as Hodges’s subordinate used to shoot skeet and hunt quail with him on Sunday mornings at Fort Benning, later recalled, “He was very dignified and I can’t imagine anyone getting familiar with him.” Now his superior, Bradley still called him “sir.”

FIRST ARMY WAS THE LARGEST American fighting force in Europe, and Hodges was the wrong general to command it. Capable enough during the pursuit across France, he now was worn by illness, fatigue, and his own shortcomings—“an old man playing the game by the rules of the book, and a little confused as to what it was all about,” a War Department observer wrote. “There was little of the vital fighting spirit.” Even the army’s official histories would describe his fall campaign as “lacking in vigor and imagination,” and among senior commanders he was “the least disposed to make any attempt to understand logistic problems.” He was “pretty slow making the big decisions,” a staff officer conceded, and he rarely left Spa to visit the front; for nearly two months the 30th Infantry Division’s Major General Leland Hobbs never laid eyes on him. Peremptory and inarticulate, Hodges “refused to discuss orders, let alone argue about them,” one military officer later wrote. He sometimes insisted that situation reports show even platoon dispositions—a finicky level of detail far below an army commander’s legitimate focus—and he complained in his war diary that “too many of these battalions and regiments of ours have tried to flank and skirt and never meet the enemy straight on.” He believed it “safer, sounder, and in the end, quicker to keep smashing ahead.” “Straight on” and “smashing ahead” would be Hodges’s battlefield signature, with all that such frontal tactics implied.

Peevish and insulated, ever watchful for hints of disloyalty, Hodges showed an intolerance for perceived failure that was harsh even by the exacting standards of the U.S. Army. Of the 13 corps and division commanders relieved in 12th Army Group during the war, 10 would fall from grace in First Army, the most recent being Major General Charles Corlett of XIX Corps after the German surrender at Aachen earlier in the month. When the frayed commander of the 8th Infantry Division requested brief leave after his son was killed in action, Hodges sacked him. The army historian Forrest Pogue described one cashiered officer waiting by the road for a ride to the rear, belongings piled about him “like a mendicant.”

Such a command climate bred inordinate caution, suppressing both initiative and élan, and the men making up First Army’s senior staff made it worse. “Aggressive, touchy, and high-strung,” Bradley later wrote of the staff he had created before ascending to 12th Army Group, “critical, unforgiving, and resentful of all authority but its own.” Three rivalrous figures played central roles in this unhappy family: Major General William B. Kean, the able, ruthless chief of staff who was privately dubbed Captain Bligh and to whom Hodges ceded great authority; Brigadier General Truman C. Thorson, the grim, chain-smoking operations officer nicknamed Tubby but also called Iago after the Shakespearean character who schemes to bring down his commander; and Colonel Benjamin A. Dickson, the brilliant, turbulent intelligence chief long known as Monk, a histrionic man of smoldering grievances.

Not least of First Army’s quirks as it prepared to renew the drive toward the Rhine was what one correspondent called “slightly angry bafflement” at continued German resistance, a resentment that the enemy did not know he was beaten. As the members of this colicky command group settled into Spa and prepared for the coming campaign, they all agreed with the GIs: It was time to take the “hit” out of Hitler.

ON OCTOBER 28, General Dwight D. Eisenhower reiterated his plan for winning the war. “The enemy has continued to reinforce his forces in the West,” he cabled his lieutenants. “Present indications are that he intends to make the strongest possible stand on the West Wall, in the hope of preventing the war spreading to German soil.” (West Wall referred to the fortified line of German defenses running along the country’s western border, which the Allies often called the Siegfried Line.) Antwerp was on the verge of falling to the Canadian First Army. With that, the final battle for Europe would unfold, he said, in “three general phases”: an unsparing struggle west of the Rhine, the seizure of bridgeheads over the river, and finally a mortal dagger thrust into the heart of Germany. Seven Allied armies would advance east apace, arrayed from north to south: the Canadian First; the British Second; the U.S. Ninth, First, Third, and Seventh; and the French First. The enemy’s industrial centers in the Ruhr and the Saar regions remained paramount objectives in the north and center, respectively, with Berlin as the ultimate target.

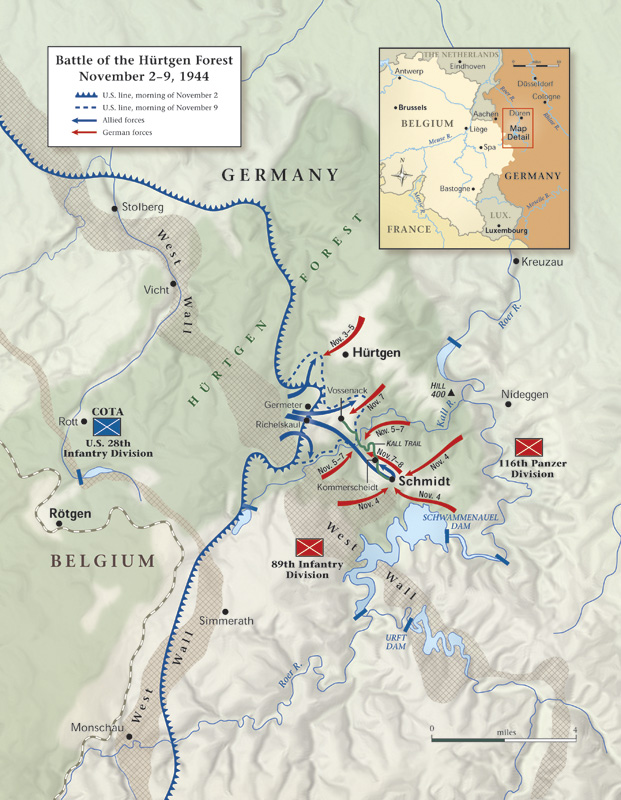

First Army’s capture of Aachen and breach of the Siegfried Line in the adjacent Stolberg corridor left barely 20 miles to traverse before the Rhine. Here lay the most promising frontage on the entire Allied line. Hodges, with assistance from Lieutenant General William Hood Simpson’s Ninth Army, was to sweep forward another 10 miles to the Roer River, overrun the town of Düren on the far bank, then press on toward Cologne and the Rhine. Joe Collins’s VII Corps would again lead the attack, but first, V Corps on his right was to clear out the Hürtgen Forest and capture the high-ground village of Schmidt, providing First Army with more maneuver room and forestalling any counterattack into VII Corps’s right flank by enemies who might be skulking in the forest dark.

Four compact woodland tracts formed the Hürtgen, 11 miles long and 5 miles wide in all. For generations, forest masters had meticulously pruned undergrowth and managed logging, leaving perfectly aligned firs as straight and regular as soldiers on parade, in what one visitor called “a picture forest.” But some of its acreage grew wild, particularly along creek beds and in the deep ravines where even at midday sunlight penetrated only as a dim rumor. Here was the Grimm forest primeval, a place of shades. “I never saw a wood so thick with trees as the Hürtgen,” a GI later wrote. “It turned out to be the worst place of any.”

The Hürtgenwald had been fortified as part of the Siegfried Line, beginning in 1938. German engineers more recently had pruned timber for fields of fire, built log bunkers with interlocking kill zones, and sowed mines by the thousands on trails and firebreaks; along one especially vicious trace, a mine could be found every eight paces for three miles. The 9th Division in late September had learned how lethal the Hürtgen could be when its troops tried to cross the forest as part of the initial VII Corps effort to outflank Aachen. One regiment took four days to move a mile; another needed five. By mid-October the division was still far short of Schmidt and had suffered 4,500 casualties to gain 3,000 yards—a man down every two feet—and no battalion in the two spearhead regiments could field more than 300 men. More and more of the perfect groves were gashed yellow with machine-gun bullets or reduced to charred stumps—“no birds, no sighing winds, no carpeted paths,” Forrest Pogue reported. A commander who offered his men $5 for every tree found unscarred by shellfire got no takers. Pogue was reminded of the claustrophobic bloodletting of May 1864 in another haunted woodland, one in eastern Virginia: “There was a desolation,” he wrote, “such as one associated with the Battle of the Wilderness.”

Nearly half of the 6,500 German defenders from the 275th Division had been killed, wounded, or captured in checking the 9th Division; reinforcements included two companies of Düren policemen known as “family fathers” because most were at least 45 years old. More bunkers were built, more barbed wire uncoiled, more mines sown, including nonmetallic shoe and box mines, and lethal round devices said to be “no larger than an ointment box.” Enemy officers considered it unlikely that the Americans would persist in attacking through what one German commander called “extensive, thick, and nearly trackless forest terrain.”

That underestimated American obstinacy. The Hürtgen neutralized U.S. military advantages in armor, artillery, air power, and mobility, but Hodges was convinced that no First Army drive to the Roer was possible without first securing the forest and capturing Schmidt, from which every approach to the river was visible. He likened the menace on his right flank to that posed by German forces in the Argonne Forest to the American left flank during General John J. Pershing’s storied offensive on the Meuse in the autumn of 1918. This specious historical analogy—the Germans could hardly mass enough armor in the cramped Hürtgen to pose a mortal threat—received little critical scrutiny within First Army, not least because of reluctance to challenge Hodges. In truth, “the most likely way to make the Hürtgen a menace to the American Army,” the historian Russell F. Weigley later wrote, “was to send American troops attacking into its depths.”

No consideration was given to bypassing or screening the forest or to outflanking Schmidt from the south by sending V Corps up the vulnerable attack corridor through Monschau, 15 miles below Aachen. Senior officers in First Army would spend the rest of their lives trying to explain the tactical logic behind their Hürtgen battle plan. “All we could do was sit back and pray to God that nothing would happen,” Major General Truman Thorson, the operations officer, later lamented. “It was a horrible business, the forest….We had the bear by the tail, and we just couldn’t turn loose.” Even Joe Collins, who enjoyed favorite-son status with Hodges, conceded that he “would not question Courtney.”

“We had to go into the forest in order to secure our right flank,” Collins said after the war. “Nobody was enthusiastic about fighting there, but what was the alternative?…If we would have turned loose of the Hürtgen and let the Germans roam there, they could have hit my flank.”

NO LESS REGRETTABLE was a misreading of German topography. Seven dams built for flood control, drinking water, and hydroelectric power stood near the headwaters of the Roer, which arose in Belgium and spilled east through the German highlands before flowing north across the Cologne plain and eventually emptying into the Maas southeast of Eindhoven. Five of the seven dams lacked the capacity to substantially affect the river’s regime, but the other two—the Schwammenauel and the Urft—impounded sizable lakes that together held up to 40 billion gallons. In early October, the 9th Division’s intelligence officer had warned that German mischief could generate “great destructive flood waves” as far downstream as the Netherlands. Colonel Dickson, First Army’s intelligence chief, disagreed. Opening the floodgates or destroying those two dams would cause “at the most local floodings for about five days,” Dickson asserted. No terrain analysis was undertaken, nor were the dams mentioned in tactical plans. “We had not studied that particular part of the zone,” Collins later acknowledged. “That was an intelligence failure, a real combat intelligence failure.”

By late October, as First Army coiled to resume its attack, unnerving details about the Roer and its waterworks had begun to accumulate. A German prisoner disclosed that arrangements had been made to ring Düren’s church bells if the dams upstream were blown. A German engineer interrogated in Spa intimated that a wall of water could barrel down the Roer. Inside an Aachen safe, an American lieutenant found Wehrmacht plans for demolishing several dams; by one calculation, 100 million metric tons of water could flood the Roer valley for 20 miles, transforming the narrow river to a half-mile-wide torrent.

A top secret memo to Hodges from Ninth Army’s General Simpson on November 5 cited a Corps of Engineers study titled “Summaries of the Military Use of the Roer River Reservoir System,” which concluded that the enemy could “maintain the Roer River at flood stage for approximately ten days…or can produce a two-day flood of catastrophic proportions.” An American attack over the Roer might be crippled, with tactical bridges swept away and any troops east of the river isolated and annihilated. Obviously neither the First Army nor the Ninth, farther downstream to the northwest, could safely cross the Roer and make for the Rhine until the dams were neutralized. Simpson proposed to Hodges that he immediately “block these [enemy] capabilities.” A flanking attack toward Schmidt from Monschau in the south would also permit capture of Urft, Schwammenauel, and their sisters.

Yet First Army hewed to its plan for a frontal assault, afflicted by what General Thorson later called “a kind of torpor in our operations.” Hodges in late October had told Bradley that the Roer reservoirs were half empty—unaware that they were being replenished—and that “present plans of this army do not contemplate immediate capture of these dams.” It was assumed that, if necessary, bombers could blow open the reservoirs whenever the army asked. Bradley would later claim that by mid-October “we were very much aware of the threat they posed” and that the “whole point” of the renewed attack through the Hürtgen was “to gain control of the dams and spillways.” That was untrue. Not until November 7 did Hodges order V Corps to even begin drafting plans to seize the dam sites, and not until December 4 would Bradley’s war diary note: “Decided must control Roer dam.”

By that time another frontal assault through horrid terrain had come to grief, and officers at Spa were reduced to feeble maledictions. “Damn the dams,” they would tell one another again and again. “Damn the dams.”

ATTACKING THE WORST PLACE OF ANY now fell to Major General Norman “Dutch” Cota and his 28th Division, still recovering from the September skirmishes that had revived the division’s World War I nickname, the Bloody Bucket, so called for their red keystone insignia. The 28th had regained full strength but only with many replacements untrained as infantrymen, under officers and sergeants plucked from antiaircraft units and even the Army Air Forces. Ernest Hemingway, who for several weeks would live in a fieldstone house south of Stolberg near the village of Vicht while filing reports for Collier’s, suggested that it would “save everybody a lot of trouble if they just shot them as soon as they got out of the trucks.”

In late October the Bloody Bucketeers—as they called themselves with sardonic pride—assembled beneath the yellow-gashed firs. GIs heaved logs into the firebreaks in hopes of tripping mines, or probed the ground inch by inch with a bayonet held at a 30-degree angle, or with a No. 8 wire. Dead men from the 9th Division still littered the forest, bullet holes in their field jackets like blood-ringed grommets. After a soldier ran over a Teller mine with his jeep, a lieutenant wrote, “His clothing and tire chains were found 75 feet from the ground in the tree tops. It snows every day now.” A few men had overshoes; the rest, trying to avoid trench foot by standing on burning Sterno blocks, soon lost any scruples about stripping footwear from the dead.

Foul weather, supply shortages, and the slow arrival of two more divisions caused First Army to postpone VII Corps’s main attack toward Düren until mid-November. An offensive in the north by 21st Army Group was also pushed back. But Hodges saw no reason to delay clearing the Hürtgen and seizing Schmidt. On Wednesday, November 1, after lunch in Spa with the V Corps commander, Major General Leonard T. Gerow, Hodges made a rare visit to a division command post. He drove 20 miles to Rott, strode into the gasthaus where Cota had put his headquarters, and voiced his pleasure that the 28th Division was obviously “in fine fettle, rarin’ to go.” The battle plan, Hodges informed Cota, was “excellent.”

In fact, it was badly flawed. For two weeks across the 170-mile front of the First and Ninth Armies, the 28th Division would be the only U.S. unit launching an attack, attracting the undivided attention of German defenders who already knew precisely where the Blutiger Eimer (Bloody Bucket) division was assembling. The “excellent” plan, imposed on Cota by V Corps staff officers far from the front squinting at a map, required him to splinter his force by attacking on three divergent axes: one regiment to the north, another to the southeast, and a third to the east, toward Schmidt. Cota’s misgivings had been waved away despite his warrant that the attack had no more than “a gambler’s chance” of success. A large sign posted in the forest warned, “Front line a hundred yards. Dismount and fight.”

At 9 a.m. on November 2, a cold, misty Thursday, GIs heaved themselves from their holes like doughboys going over the top. Eleven thousand artillery rounds chewed up German revetments and flayed the forest with steel from shells detonating in the tree canopy. But the brisk brrrr of machine-gun fire from pillboxes on the division’s right flank mowed down men in the 110th Infantry Regiment—“singly, in groups, and by platoons,” the division history recorded. By day’s end the 110th had gained not a yard, and by week’s end the regiment would be rated “no longer an effective fighting force.”

The attack began no better for the 109th Regiment on the left flank. German sappers driving charcoal-fueled trucks had hauled enough mines from a Westphalian munitions plant to lay a dense field in a swale across the road from the village of Germeter to Hürtgen village. The 109th had advanced barely 300 yards when a sharp pop was followed by a shriek: a GI clutched his bloody foot. More pops followed, more shrieks, more maimed boys. After 36 hours the regiment would hold only a narrow, mile-deep salient into enemy territory, a salient almost mirrored by Germans infiltrating the U.S. ranks.

Against such odds, and to the surprise of American and German alike, the division’s main attack won through in the center. A battalion from the 112th Infantry was pinned wriggling to the ground by enemy fire near the village of Richelskaul, but seven Shermans churned down the wooded slope from Germeter, each trailing clouds of infantrymen holding a rear fender and trotting in the tank tracks to avoid mines. The Shermans fired four rounds apiece to dismember the church steeple in the town of Vossenack and any snipers hidden in the belfry, and 200 white-phosphorus mortar shells set the village ablaze. One block wide and 2,000 yards long, Vossenack straddled a saddleback two miles from Schmidt, visible through the haze to the southeast. Soft ground, mines, and panzerfaust volleys wrecked five Shermans, but before noon burning Vossenack belonged to Cota’s men, who burrowed into the northeast nose of the ridgeline.

AT DAWN ON FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 3, the attack resumed. From Vossenack the ridge plunged into the crepuscular Kall gorge, a deep ravine carved through the landscape by a stream rushing toward the Roer. Two American battalions in column spilled down a twisting cart track, then forded the icy Kall near an ancient sawmill and emerged from the beeches limning the far ridge to pounce on the drab hamlet of Kommerscheidt. The 3rd Battalion scampered southeast for another half mile and at 2:30 p.m. fell on the astonished garrison at Schmidt, capturing or killing Germans eating lunch, riding bicycles, or nipping schnapps on the street.

From rooftops in the 16th-century town, the entire Hürtgen swam into view, along with the meandering Roer two miles to the east and the sapphire Schwammenauel reservoir a mile south. A believing man with imagination could almost see the end of the war.

Telephoned congratulations from division and corps commanders across the front poured into Cota’s headquarters in Rott, 10 miles to the west. General Hodges himself sent word that he was “extremely satisfied.” The plaudits, Cota later said, made him feel like “a little Napoleon.”

The bad news from Schmidt reached Field Marshal Walter Model that same afternoon at Schlenderhan castle in the horse country west of Cologne, hardly 25 miles from the battlefield. There by chance Model had just started a map exercise with his top commanders, positing a theoretical American attack near the Hürtgenwald. Sketchy reports indicated that in fact a strong assault against the German LXXIV Corps threatened to overrun the Roer dams that generated much of the electricity west of the Rhine.

Model ordered the corps commander back to his post, but other officers—including two army commanders—were instructed to continue the war game, using dispatches from the front to help orchestrate the battle. Low clouds and fog had impaired Allied fighter-bombers for the past two days; with luck, reinforcements could hasten forward, unimpeded, on the good roads threading the Roer valley. Confrontation with the Americans would first fall to the 116th Panzer Division, which had fought through Yugoslavia and southern Russia as far as the Caspian Sea before surviving more recent battles in the west, at Falaise and Aachen. The reconnaissance battalion was already galloping toward Schmidt, followed by the bulk of the division and by troops from the 89th Infantry Division.

Three isolated American rifle companies and a machine-gun platoon from the 112th Infantry defended Schmidt, unaware of the Wehrmacht high command’s keen interest but unnerved by snipers and haystacks on a hillside that seemed to move in the moonlight. Exhausted after Friday’s trudge through the Kall gorge in heavy overcoats with full field packs, the 3rd Battalion sent out no patrols and scattered 60 antitank mines—delivered during the night by tracked M29 Weasel cargo carriers—on three approach roads without attempting to implant or camouflage them. No panzer counterattack was considered likely given Allied air superiority and the destruction of German armor in the past two months. Oblivious to his men’s vulnerability, Cota remained in Rott; not for three more days would he visit the front. Having already committed his only division reserve to help the hard-pressed 110th Infantry in the south, the little Napoleon had lost control of the battle before it really began.

Just before sunrise on Saturday, November 4, German artillery fire crashed and heaved from three directions around Schmidt. A magnesium flare drifted across the pearl-gray dawn, and wide-eyed GIs spied a long column of Panthers and Mk IVs snaking toward them from the northeast, easily swerving around the pointless mines. German machine-gun bullets ripped through foxholes; scarlet tank fire blew the town apart, house by house. Mortar pits were overrun, bazooka rounds bounced off panzer hulls like marbles, and yowling enemy infantrymen raced toward Schmidt from the south, west, and east, some banging on their mess kits in a lunatic tintinnabulation.

At 8:30 an American platoon on the southern perimeter broke in panic, unhinging the defense. Soon the entire battalion took to its heels, Companies I, K, and L scrabbling through gardens and over fences, “ragged, scattered, disorganized infantrymen,” in one lieutenant’s account. Barking officers grabbed at their soldiers’ herringbone collars in an attempt to turn them, but hundreds leaked down the road toward Kommerscheidt, forsaking their dead and wounded. Two hundred others stampeded in the wrong direction—southwest, into German lines—and of those only three would elude capture or worse. By 10 a.m., Schmidt once again belonged to the Reich.

THE FIGHT FOR THE HÜRTGEN had taken a turn, though it was several hours before the command post in Rott got word that an infantry battle had become a tank brawl. Lowering clouds grounded Allied pilots for a third day, and U.S. intelligence was slow to realize that enemy observers with Zeiss optics on Hill 400, just two miles north of Schmidt, could see even a rabbit cross the meadows on either flank of the Kall gorge. Confusion soon turned to chaos, calamity to farce. A tank company trying to negotiate the steep Kall trail managed, with a great deal of winching around the hairpin turns, to get three Shermans across the ravine to help repel an initial German lunge at Kommerscheidt from Schmidt. But five other tanks stood disabled, repeatedly throwing tracks on the treacherous switchbacks and blocking the path, which at nine feet was precisely as wide as a medium tank. After nightfall, in relentless rain and stygian darkness, engineers hacked at the trail with picks and shovels—a bulldozer broke down half an hour after arriving—but even the nimble Weasels seemed clay footed, and the ammunition trailers they towed had to be unhitched and manhandled around each sharp turn into and out of the gorge.

In Rott, Cota’s perplexity only deepened. Radios worked fitfully, and messengers were ambushed or forestalled by descending curtains of artillery. Was the Kall Trail open? No, came the reply, then yes, then no. Engineers detonated captured Teller mines in a futile attempt to blow apart a rocky knob blocking a switchback above the pretty stone bridge spanning the creek; 300 pounds of TNT finally reduced the obstruction. Tank crews showed little sense of urgency—“Everybody appeared to treat the disabled tanks with the same kind of warmhearted affection an old-time cavalryman might lavish on his horse,” the army’s official history acknowledged. Not until 2:30 a.m. on Sunday, November 5, just before moonrise, were the stalled Shermans finally shoved over the brink into the gorge.

A fretful General Gerow, the V Corps commander, drove into Rott a few hours later, clucked at Cota, drove off, and soon returned with Hodges and Joe Collins. Pulling on an Old Gold, Hodges also berated Cota, but then rounded on Gerow in a crimson tirade—“tougher than I had ever heard him before,” Collins later recalled. “He was pushing Gerow awfully hard.” Cota was reduced to scribbling another order that might or might not reach the 112th Infantry: “It is imperative that the town of Schmidt be secured at once.” He ended the message: “Roll on.”

Had the generals seen the battlefield clearly, reclaiming Schmidt would have been the least of their concerns. Enemy forces now crowded the 28th Division on three sides, threatening the Bloody Bucket with annihilation. Nine Shermans and nine tank destroyers had traversed the Kall to reach the remnants of two infantry battalions huddled in what was described as a “covered wagon” defense in Kommerscheidt. Just the rumor of another panzer attack sent spooked riflemen scouring for the gorge, but any illusion of refuge there soon vanished. On Sunday night, reconnaissance troops from the 116th Panzer clattered down the Kall creek bed past an old sawmill, through ferns half as high as a man. Army engineers grooming the trail ran for their lives, as German sappers mined the switchbacks, set up ambushes, and cut off more than a thousand GIs east of the ravine.

Dawn on Monday laid bare the American plight. Panzer drumfire from Schmidt soon reduced nine Shermans to six, and nine tank destroyers to three. GIs unable to leave their flooded rifle pits, described as “artesian wells,” were once again reduced to defecating in empty C-ration cans. Those gimlet-eyed German observers on Hill 400 lobbed 20 artillery rounds or more onto each position, shifting guns hole by hole by hole; sobbing men waited in terror as the footfall drew closer.

A relief battalion from the 110th Infantry that had been ordered to huddle together for warmth in Vossenack—“just like cattle do in a storm,” one survivor reported—attracted a 30-minute artillery barrage. Men were “killed right and left as they were milling around….Everybody was trying to jump over a bleeding body to find shelter.” One company lost 41 of 127 men, another 75 of 140. “Lieutenant, are my legs still there?” a wounded soldier asked his platoon leader. “Please tell the truth.”

Soldiers in the claustrophobic forest debated whether they could stave off the enemy long enough to finish smoking the carton of cigarettes they carried, or merely an open pack, or perhaps only the Lucky Strike they had just lighted. Examining a badly wounded man for injuries in the dark woods, a 28th Division medic reported, was “like putting your hand in a bucket of wet liver.” A surge in head wounds stirred debate in the ranks about whether German snipers were aiming at the bloody bucket insignia painted on their helmets. “So this is combat,” a lieutenant new to the Hürtgen reflected. “I’ve only had one day of it. How does a man stand it, day in and day out?”

How, indeed? The morning wore on, and the existential crisis sharpened. The 2nd Battalion of the 112th Infantry, whose two sister battalions were trapped in Kommerscheidt, finally broke after four nights of murderous shelling on the exposed nose west of the Kall gorge. An abrupt, piercing scream unmanned Company G, which fled for the rear through Vossenack, and the contagion instantly infected the ranks. “Pushing, shoving, throwing away equipment, trying to outrun the artillery and each other,” an officer reported, the men scorched up the ridge toward their original positions at the beginning of the Hürtgen battle four days earlier. A lieutenant who considered the pell-mell flight “the saddest sight I have ever seen,” added, “Many of the badly wounded men, probably hit by artillery, were lying in the road where they fell, screaming for help.”

Officers managed to rally 70 stout hearts near the ruined Vossenack church—no one had yet seen a single German in the village—and four tank platoons rushed down from Germeter. Cota ordered two road-repairing companies from the 146th Engineers into the line as riflemen. Still in their raincoats and hip boots, the engineers battled infiltrators all night around the church; Germans at one point occupied the tower and the basement while GIs held the nave. On Tuesday morning, November 7, the engineers helped beat back a panzergrenadier assault, keeping Vossenack in American hands except for the eastern fringe, dubbed the Rubble Pile, which the Germans would hold for another month. The 112th Infantry’s 2nd Battalion was considered “destroyed as a fighting unit,” another unit smashed to pieces.

“The 28th Division situation is going from bad to worse,” First Army’s war diary noted on Tuesday. Cota could only agree. A relief force of 400 men had fought across a firebreak in the Kall gorge to reach Kommerscheidt on Sunday, but none of the accompanying tanks or tank destroyers could bull through German roadblocks. Artillery and mortar barrages pounded Kommerscheidt through the night, and catcalling enemy infiltrators crept so close in the encroaching draws that Jewish GIs hammered out the telltale H—for Hebrew—on their dogtags. As the gray skies spat sleet, 15 panzers and 2 infantry battalions renewed the attack on Tuesday morning, shooting up farmsteads and garden shacks. By midday the Americans had fallen back to entrenchments along the eastern lip of the gorge, and Kommerscheidt too was lost.

Reeling from lack of sleep and grieving for his gutted command, Cota phoned Gerow to propose that survivors marooned across the ravine retreat to a new line west of the Kall. Shortly before midnight on Tuesday, Gerow called back with permission. Hodges, he added, was “very dissatisfied….All we seem to be doing is losing ground.” Not until 3 p.m. on Wednesday, November 8, did the withdrawal order reach the battered last-stand redoubt. Soldiers at dusk fashioned litters from tree limbs and overcoats. Others smashed radios, mine detectors, and the engine blocks on four surviving jeeps; three antitank guns were spiked and the only functioning Sherman booby-trapped. Soldiers shed their mess kits and other clattering gear—the senior officer among them mistakenly threw away his compass—and engineers abandoned two tons of TNT with which they had planned to demolish pillboxes in Schmidt.

Come nightfall, American artillery smothered Kommerscheidt with high explosives to hide the sounds of withdrawal, and two columns slipped into the gorge. A smaller group of litter-bearers carried the wounded down the trail, past GI corpses crushed to pulp by the earlier armor traffic, while several hundred “effectives” set out cross country, each grasping the shoulder of the man in front and moving through woods so dark they produced the illusion of walking into a lake at midnight. Charles B. MacDonald, the author of the army’s official account, described the retreat: “Like blind cattle the men thrashed through the underbrush. Any hope of maintaining formation was dispelled quickly by the blackness of the night and by German shelling. All through the night and into the next day, frightened, fatigued men made their way across the icy Kall in small irregular groups, or alone.”

Of more than 2,000 American soldiers who had fought east of the Kall, barely 300 returned. German pickets in the gorge let some wounded pass; others were detained for two days near a log dugout above the rushing creek, whimpering in agony until a brief cease-fire permitted evacuation. The dead accumulated in stiff piles, covered with fir branches until graves registration teams could bear them away.

Eisenhower and Bradley had driven to Rott on Wednesday morning, disconcerted by reports of an attack gone bad. At headquarters, the supreme commander listened to Cota’s account and then said with a shrug, “Well, Dutch, it looks like you got a bloody nose.” Hodges and Gerow arrived a few minutes later for a hurried conference. With Germans still entrenched on the high ground at Schmidt, any November offensive to the Rhine now stood in jeopardy.

After Eisenhower left, Hodges gave Cota yet another tongue lashing. Had the regiments been properly deployed and dug in? If they had been, even under heavy German artillery fire, casualties “would not be high nor would ground be lost.” During the battle, Hodges complained, the division staff appeared to have “no precise knowledge of the location of their units and were doing nothing to obtain it.” The First Army commander wanted Cota to know that he was “extremely disappointed.” Before driving back to Spa, Hodges told Gerow that “there may be some personnel changes made.”

The gray weather grew colder. Sleet turned to heavy snow, and winter’s first storm was on them. Vengeful GIs rampaged through German houses, smashing china and tossing furniture into the streets. “I’ve condemned a whole regiment of the finest men that ever breathed,” a distraught officer told reporter Iris Carpenter. “I tell you frankly, I can’t take much more of it.”

Survivors from the Kall were trucked to Rötgen, where pyramidal tents had been erected with straw floors and stacks of wool blankets. Medics distributed liquor rations donated by rear-echelon officers. Red Cross volunteers served pancakes and beer, and the division band played soldierly airs. “Chow all right, son?” a visiting officer asked one soldier, who without looking up, replied, “What the fuck do you care? You’re getting yours, aincha?”

ON THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 9, the 28th Division began planting a defensive barrier of 5,000 mines around the cramped salient held in the Hürtgen. Patrols crept through the lines searching for hundreds of missing GIs in the once perfect ranks of trees, now quite imperfect. The weeklong battle had been among the costliest division attacks of the war for the U.S. Army, with casualties exceeding 6,000. The Bloody Bucket was bloodier than ever: One battalion in the 110th Infantry was reduced to 57 men even after being reinforced, and losses had whittled the 112th Infantry from 2,200 to 300. “The division had accomplished very little,” the unit history conceded.

In less than six months, Dutch Cota had gone from a man lionized for his valor at Omaha Beach and St. Lô to a defeated general on the brink of dismissal: Such was war’s inconstancy. He was permitted to keep his command partly because so many other leaders had been lost in the division that four majors and a captain led infantry battalions. In mid-November, the 8th Division arrived in the Hürtgen to replace the 28th, which was shunted to a placid sector in the Ardennes for rest and recuperation. To his troops, Cota issued a message of encouragement, which closed with the injunction “Salute, March, Shoot, Obey.”

German losses for the week had totaled about 3,000. “We squat in an air-less cellar,” a German medic wrote his parents. “The wounded lie on blood-stained mattresses….One has lost most of his intestines from a grenade fragment.” Another soldier, with an arm and a foot nearly severed, pleaded, “Comrades, shoot me.”

On the American side of the line, U.S. quartermaster troops dragged dead Germans feet first from a wrecked barn, while a watching GI strummed his guitar and belted out “South of the Border.” But the enemy kept its death grip on the forest. Single American divisions continued to gnaw and be gnawed: Attacks in coming days by the 4th and 8th Infantry Divisions, like those by the 9th and the 28th, gained little at enormous cost, with battalions reduced to the size of companies and companies shaved to platoons. “The days were so terrible that I would pray for darkness,” one soldier recalled, “and the nights were so bad that I would pray for daylight.”

IN LESS THAN THREE MONTHS, six U.S. Army infantry divisions would be tossed into the Hürtgen, plus an armored brigade, a Ranger battalion, and sundry other units. The Allied commanders’ poor comprehension of the importance of securing the dams—so the Roer could be vaulted, the Rhine attained, and the Ruhr captured—would come back to haunt them. The Urft finally fell in early February, but only because German defenders had rallied round the Schwammenauel and the 20 billion gallons it impounded. For nearly a week the green 78th Division, reinforced by a regiment from the 82nd Airborne and eventually the veteran 9th Division, had retaken ground won and then lost in the Hürtgen battles of late fall: the Kall gorge—where dozens of decaying, booby-trapped corpses of 28th Division troops still lined the trail—and then Kommerscheidt, and finally ruined Schmidt, captured in a cellar-to-cellar gunfight on February 8 after 40 battalions of U.S. artillery made the rubble bounce. But the Germans, who by then had had plenty of time to prepare for just this exigency, blew the Schwammenauel’s valves open, which, along with the snowmelt and rain, made the Roer impossible to bridge. Fifteen American divisions otherwise poised to drive on Berlin were stranded on the west side of the river for another two weeks.

All told, 120,000 soldiers sustained 33,000 casualties in what the historian Carlo D’Este would call “the most ineptly fought series of battles of the war in the West.” A captured German document reported that “in combat in wooded areas the American showed himself completely unfit,” a harsh judgment that had a whiff of legitimacy with respect to American generalship.

As the attack in the Hürtgen continued to sputter in late November, Hodges himself showed the strain. “He went on and on about how we might lose the war,” Major General Pete Quesada, the commander of IX Tactical Air Command, said after one unhappy conference. Despite the setback, Hodges and his command group soldiered on: At a November dinner party in the Spa generals’ mansion, the table was decorated with the distinctive black A of First Army’s shoulder flash, originally adopted in 1918. For dessert, each guest received an individual cake with the officer’s name stenciled in pink frosting, and with coffee the film Janie was shown, a romantic comedy starring Joyce Reynolds.

One soldier-poet composed a verse that ended, “We thought woods were wise but never / Implicated, never involved.” Yet in the Hürtgen surely terrain and flora were complicit, the land always implicated. An engineer observed that the forest “represented not so much an area as a way of fighting and dying.” A coarse brutality took hold in Allied ranks, increasingly common throughout Europe. Fighter-bombers incinerated recalcitrant towns with napalm, and one potato village after another was blasted to dust by artillery. “C’est la bloody goddam guerre,” soldiers told one another. Among those sent to the rear for psychiatric examination were two GI collectors, one with a cache of ears sliced from dead Germans and another with a souvenir bag of teeth. Through the long winter, feral dogs in the forest would feed on corpses seared by white phosphorus. “This was my personal Valley of the Shadow,” a medic wrote. “I left with an incredible relief and with a sadness I had never so far known.”

From his fieldstone house, furnished with a potbelly stove and a brass bed in the living room, Hemingway rambled about in a sheepskin vest. Sometimes on request he ghost-wrote love letters for young GIs, reading his favorite passages to fellow journalists. He would memorably describe the Hürtgen as the equivalent of the Great War’s bloody Battle of Passchendaele, except “with tree bursts,” but not even a Hemingway could quite capture the debasement of this awful place. A soldier asked Iris Carpenter as she scribbled in her reporter’s notepad, “Do you tell ’em their brave boys are livin’ like a lot of fornicatin’ beasts, that they’re doin’ things to each other that beasts would be ashamed to do?” A veteran sergeant who believed the Hürtgen more wretched than anything he had experienced in North Africa, Sicily, or Normandy, quoted King Lear, act 4, scene 1: “The worst is not / So long as we can say ‘This is the worst.’”

To a soldier named Frank Maddalena, who went missing in the forest in mid-November, his wife, Natalie, mother of his two children, wrote from New York: “I see you everywhere—in the chair, behind me, in the shadows of the room.” In another note she added, “Still no mail from you. I really don’t know what to think anymore. The kids are fine and so adorable. Right now, I put colored handkerchiefs on their heads and they are dancing and singing….When I walk alone, I seem to feel you sneaking up on me and putting your arms around me.”

No, that did not happen, would not, could not. This is the worst.

Rick Atkinson won the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for An Army at Dawn, the first volume in his World War II Liberation Trilogy. This article is excerpted from the third and final installment, The Guns at Last Light: The War in Western Europe, 1944–1945, by Rick Atkinson. Copyright © 2013. Reprinted by arrangement with Henry Holt and Company LLC.