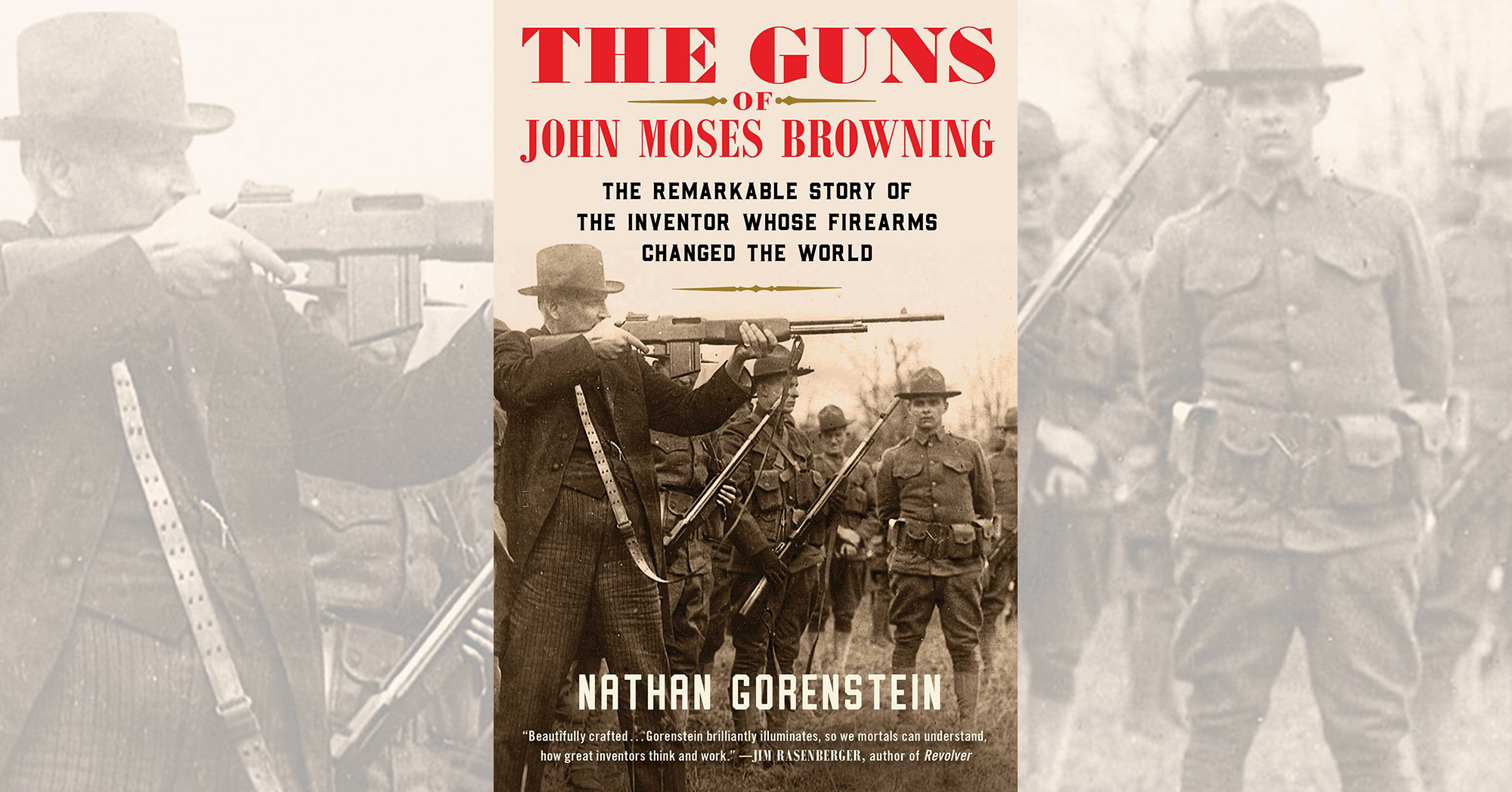

The Guns of John Moses Browning: The Remarkable Story of the Inventor Whose Firearms Changed the World, by Nathan Gorenstein, Scribner, New York, 2021, $28

It is no exaggeration to say that inventor John Browning’s firearms changed the world. The holder of 128 firearm patents, he invented such seminal military guns as the Colt M1911 semiautomatic pistol, the Winchester Model 1897 pump-action shotgun, the M1895 gas-operated machine gun, the .50-caliber M2 (“Ma Deuce”) machine gun and the M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle (the BAR of World War II fame). According to author Nathan Gorenstein, manufacturers worldwide have rolled out an estimated 35–40 million firearms patterned after the inventor’s designs. That number, Gorenstein concedes, is almost certainly too low when one considers the countless knockoffs, as well as firearms influenced by Browning’s designs. “As Henry Ford was to automobiles, and Thomas Edison was to electricity,” the author writes, “Browning was to firearms.” Yet for most of his life the brilliant inventor remained obscure. Gorenstein aims to remedy that with this first comprehensive biography of Browning.

Browning came from humble, prodigious stock. Born in Ogden, Utah Territory, in 1855, he was the son of Mormon gunsmith Jonathan Browning, who with his three wives fathered 22 children. John (No. 13) tinkered in his father’s workshop from age 6 and by his mid-teens was a skilled metalworker who could repair or copy any gun dropped off at the shop. It was a living, but not enough for the talented and curious young man. As he’d handled virtually every available firearm, Browning’s mind hummed with ideas for improvements and entirely novel actions. “As soon as I started to make the gun,” he recalled, “I found my head so full of parts that my greatest difficulty was sorting them out.” Thinking in three dimensions, he eschewed blueprints in favor of trial-and-error cutting, chiseling, drilling and filing in the workshop. In 1879 the 24-year-old filed his first patent, for what would become the Model 1885 single-shot rifle, with Browning’s innovative and robust falling-block action—the debut design of many that remain in use today.

Working in partnership with the Winchester Repeating Arms Co., Browning went on to create the popular Models 1886, 1892, 1894 and 1895 lever-action rifles, as well as the Model 1887 lever-action shotgun and the Model 1897 pump-action shotgun (the devastating American “trench gun” of World War I that, ironically, drew diplomatic protests and threats of retaliation from Germany). When Browning ultimately sought royalties from Winchester rather than the single-fee payments he’d been receiving, the company declined, prompting him to pitch his designs to other manufacturers, including Remington, Savage, Stevens and Belgium’s Fabrique Nationale (FN). Perhaps the biggest beneficiary was Colt, which produced his M1895 “potato digger” (the world’s first successful gas-operated machine gun) and the M1911, history’s most enduring semiautomatic pistol design, variants of which remains in use by military and law enforcement organizations worldwide. Browning also invented the popular .45 ACP cartridge and a half dozen other cartridges of various calibers.

Gorenstein makes no bones about the dichotomy of the gun itself. “Firearms indisputably occupy both ends of a moral spectrum starting at good and ending at evil,” he writes. “Pistols, rifles and machine guns can defend a nation and liberate a people, or conquer a land and slaughter its inhabitants.” He is also cognizant of their undeniable influence on world events. “One is hard-pressed to cite a major historic event since the mid–19th century that was not started, finished or changed by a gun.” Integral to the development and improvement of that transformative tool was Browning. “His inventions,” the author notes, “changed how hunters hunted, how armies fought, how people protected themselves, how crimes were committed, what laws were passed and how people were killed, the innocent and guilty both.” Gorenstein delves into the details behind Browning’s designs and storied career, which brought him great wealth and, ultimately, the fame he’d largely avoided in his lifetime. That remarkable life ended in 1926 after the tireless 71-year-old inventor suffered a heart attack on the FN factory floor in interwar Belgium.

—David Lauterborn

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.