[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n the morning of May 27, 1944, a British transport aircraft descended out of the clouds near the Iberian Peninsula and approached the Allied airfield at Gibraltar. A formation of military and political officials, all wearing their finest red tabs and neckties to welcome the important guest, obediently waited near the runway. Unexpectedly, the aircraft pulled into a turn and began circling the field. It lingered overhead for nearly an hour while the crowd stood by.

Finally, the pilot banked toward the run-way and landed, taxiing to the assembly who snapped back to attention. The British general for whom they all waited strode out of the airplane door and down the steps with élan. The officers immediately recognized the man’s diminutive stature, the trademark beret, the neat mustache hanging under a sharp nose, and the brow that was always furrowed as if he was looking into the sun. Bernard Law Montgomery. Monty.

“Good morning, gentlemen,” the general said, returning a salute. “Where is Foley?”

A major in the British Army, Frank Foley, stepped forward and the two men briefly chatted before leaving in a staff car manned by a driver and an armed escort. They drove to the house of the governor of Gibraltar, waving along the way to those who recognized the colors fluttering from the car’s staff. “Well, Foley,” the general remarked, looking around with an air of familiarity. “It hasn’t changed much since I was here last.”

At Government House, Foley led his guest into a large room with a table already laid out for breakfast. Montgomery’s penchant for lavish breakfasts—even while operating in the deserts of North Africa in the previous two years—had preceded him. Foley closed the door, turned, and let out a long dramatic sigh. “God, what a marvelous show!” he said. “I wouldn’t have believed it! Just wait until the governor sees you. He’ll be tickled to death.”

A few minutes later, when Foley exited the room and left him alone, the famous general became again a lieutenant no one knew—for the time being, anyway.

ONE ESSENTIAL PART OF PLANNING for the Allied invasion of Normandy was the creation of an elaborate deception campaign aimed at misleading the Germans about the location and timing of the attack. When, in late 1943, Montgomery, 56, was appointed commander of Allied forces under American general Dwight D. Eisenhower, the possibility of a new, specialized component of the deception campaign arose. Montgomery, who had successfully led the British Eighth Army in North Africa, was respected by the Germans, who would no doubt be watching his movements closely. Perhaps that could be used to advantage.

The plan, which came to be known as Operation Copperhead, got its conception in January 1944, when British deception specialist Brigadier Dudley Clarke saw a film called Five Graves to Cairo. In it, actor Miles Mander plays a British officer who bears a striking resemblance to Montgomery. If the actor, outfitted as Montgomery, made some public appearances in the Mediterranean theater shortly before the invasion, perhaps he could fool the enemy into thinking the push would come through southern France. At the very least, it would imply the invasion wasn’t imminent, since Monty was away from England.

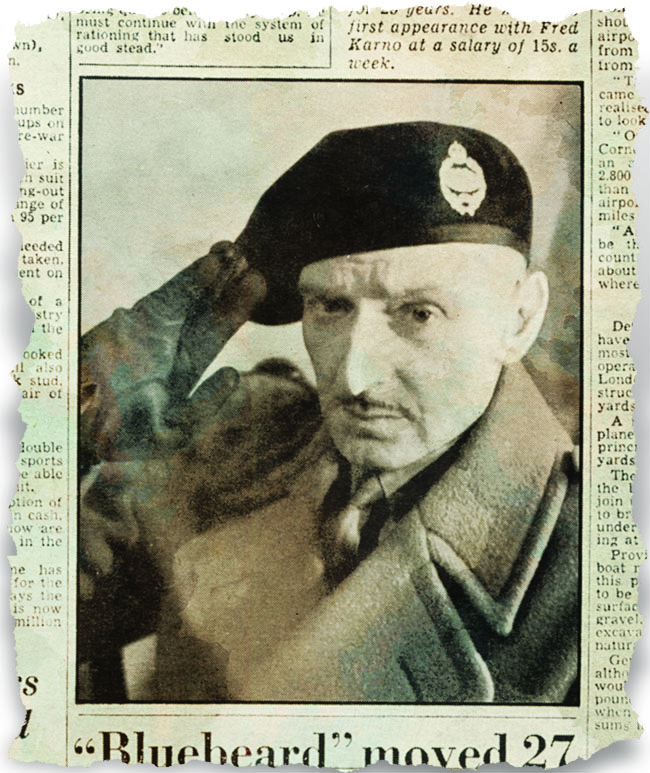

Clarke developed the concept over the next several weeks, but its implementation quickly hit a snag. When military planners met Mander in person, they discovered he was too tall to convincingly portray the five-foot-six Montgomery. Other efforts involving other actors were no more fruitful, but in May 1944 came an unexpected find. Captain Stephen Watts, an officer with MI5, the British intelligence agency, happened across a newspaper photo of British Army lieutenant M. E. Clifton James dressed as Montgomery for a stage show in Leicester. The resemblance was uncanny. An obscure Australian actor before the war, James, 46, had been assigned to the Royal Army Pay Corps, based in Leicester, and performed in shows in his spare time. Watts and Clarke quickly put the operation back in motion.

They asked Lieutenant Colonel David Niven, a well-known actor then assigned to the army’s film unit, to contact James by phone under the guise of hiring him for army training films. He instructed James to meet with a talent scout—someone James would come to know as “Colonel Lester,” a pseudonym for MI5 intelligence officer T. A. Robertson—who evaluated James’s suitability for the task. Only after James signed a nondisclosure document did Robertson tell him the real plan: “You have been chosen to act as the double of General Montgomery before D-Day.”

“The walls of the room began to sway, and his voice seemed to come from a long way off,” James later wrote. “My head began to ache and my throat felt suddenly dry.” James nevertheless accepted, despite his own uncertainty: “Could I really play such a tremendous role?”

WITH THE INVASION ONLY DAYS AWAY, the key planning team—Robertson, Watts, and a lieutenant named Jack Hervey—quickly got down to business. Because the role would involve air travel, they arranged for a trial flight to ensure James would not get airsick. At Heston Aerodrome, just west of London, James climbed into the “smallest and most decrepit airplane on the field.” The pilot took him on a 75-minute aerial jaunt through black clouds and rain and, despite the buffeting and lurching, James didn’t get sick.

For the ruse to be successful, planners recognized that details were just as important as broad strokes. They told James—to his chagrin—that he would not be permitted to drink alcohol or smoke for the duration of his act, as Montgomery abstained from both vices. And although the general enjoyed large breakfasts, he did not eat eggs or pork products and never took milk or sugar on his porridge. James would have to put aside all his personal tastes and preferences and dive into the role completely.

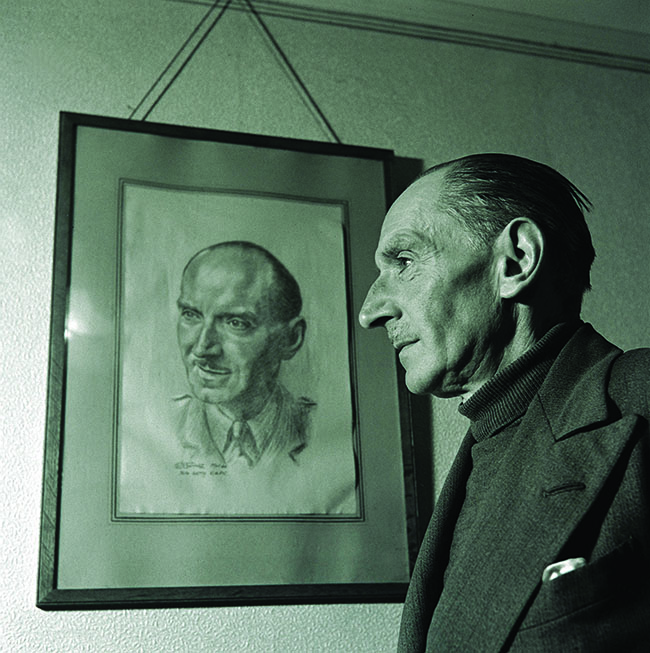

James then visited Montgomery and his staff, all of whom were dressed in an eclectic mix of military and civilian garb—berets, slacks, and cardigans—just like their general. The actor closely studied his subject, whose diminutive figure was “never still” and “strode along, dominating the scene…. Every now and then he stopped and fired questions…checking up, offering advice, issuing orders.” After an outing and lunch, James had a short meeting directly with Montgomery to learn the tone and cadence of his voice. It was an easy conversation, and even James was struck by their resemblance. “All I had to do,” he later wrote, “was to broaden my moustache, slightly whiten my greying hair—and I was General Montgomery.”

AFTER RECEIVING WORD that the general approved of James as his double, the team put the actor through repeated rehearsals using arranged chairs to represent seating inside an aircraft and a staff car. They drilled James on how he should sit in the car—Montgomery preferred the left side of the back seat—as well as how to swiftly climb in and out of the vehicles until the planners were satisfied that the actor had properly captured his subject’s habits, voice, and mannerisms.

After a final dress rehearsal on May 26, James learned that he would fly to Gibraltar for the first phase of the deception that very evening. But at that late moment, Watts noticed a detail overlooked in the bustle of preparation that threatened to derail the operation.

As a private in the Royal Fusiliers during the First World War, James had been hit by enemy fire, which severed the middle finger of his right hand. As Montgomery rarely wore gloves and waved with that hand, this was a key challenge to overcome. Watts quickly sent Hervey to obtain skin-colored adhesive plaster and cotton wool, which they used to fashion a false finger. James found it to be a “quite realistic” solution, as it gave the impression that Monty had simply cut himself and dressed it. But, still nervous, he “began to wonder whether we had overlooked anything else.”

The nerves ratcheted upward as the deception neared. “I felt restless, rather like one does on the first night of a show, when each member of the cast wonders whether it will be a smashing hit or a resounding flop,” James recalled. In this show, of course, the stakes were immeasurably higher. En route to RAF Northolt, an airfield west of London, and fearing that he “looked as much like General Montgomery as Hitler did,” James calmed when he noticed several civilians waving and smiling at his car. He assumed his role and waved back, flashing what he hoped was the “true Monty smile.” The show was on.

THE AIRCRAFT REACHED GIBRALTAR on the morning of May 27, flying past the Rock toward the airfield and circling conspicuously for an hour. With a nearby observation post known to be collaborating with the Germans, the welcoming hubbub would no doubt catch their attention. Clearly someone important was arriving, and the British were counting on those manning the post to transmit their observations up the chain of command.

At Government House, Major Foley took James to a large room to wash and shave before meeting with Gibraltar governor Sir Ralph Eastwood, who was also in on the deception. Left by himself for the first time since taking on the role, James felt a wave of loneliness rush in. “I was literally shaking,” he recalled. “I could have screamed with nerves.” But a waiter bringing a breakfast tray to the famous general snapped James back into character.

One of James’s props was a khaki handkerchief embroidered with Montgomery’s initials. After eating, James dropped it on the floor of his room, ensuring that the waiter or one of the workers would find it and believe they had the general’s own monogrammed handkerchief. The lucky person would likely brag about his treasured souvenir, and talk would spread—as intended.

After a brief meeting, Governor Eastwood led James across the grounds, chatting openly with him to keep up the appearances for all to see. James was the center of attention and noticed onlookers as they leisurely strolled back to the mansion. Hundreds of Spanish citizens lived and worked on Gibraltar; British intelligence suspected many of them of working with the Germans, and the success of the plan counted on them reporting Montgomery’s visit—which they did.

Eastwood’s car then drove them back to the airfield and, after a ceremonial farewell with waving crowds and saluting officers, James boarded the aircraft. With Gibraltar behind them, the aircraft had one more stop: Algiers.

THE NEARLY 500-MILE FLIGHT took them eastward along the coast of North Africa. Approaching Algiers, the pilot avoided a straight approach and instead flew them around behind the city to avoid attracting antiaircraft fire. Otherwise, he told James, “everyone, including the Americans, British, and French will start banging away at us.” The usual assembly of high-ranking officers waited on the tarmac, along with, James later wrote, a “motley group of French, Arabs, and every race under the sun, all eager to catch a glimpse of the great Montgomery.” He obliged them with another performance, following orders to show himself off as much as possible. A staff car, following a pair of American military policemen on motorcycles, took him on a short drive to British general Henry Maitland Wilson’s headquarters.

Once inside the large building, aides led him to an isolated room and closed the door. And suddenly, Clifton James’s performance was finished. Aides collected the general’s uniform and packed it away—along with the false finger. After he was dressed in his actual uniform, James recalled the surreal transformation: “Lieutenant Clifton James was led out of the back door of the house where shortly before General Montgomery had gone in by the front door.”

Led to an isolated villa overlooking the water, James recalled a wave of “horrible depression…a touch of anti-climax. Less than an hour ago I had been playing the part of Britain’s greatest General. Now the show was over.” Brigadier Dudley Clarke paid a visit, congratulating James on a job well done but also warning him to stay hidden until they could quietly fly him off to Cairo, where he was to lie low for an indefinite time—“a few weeks” he was told—until after D-Day.

It was a stark contrast to the past several days, during which he was the center of attention for a great many military and political figures. In Cairo, as James looked out over the sprawling web of streets and houses before him, he reflected on the uncertainty of the whole enterprise. “Had it been a success? On the stage you could tell by the applause. Here there was no applause.”

As far as the War Office was concerned, Lieutenant James had completed his assignment. On the morning of June 7, 1944, he boarded a DC-3 transport that took him on a series of bumpy and jarring flights northward to England. He reported back to Leicester, where he returned to his duties in the Royal Army Pay Corps.

IN OCTOBER 1945, only weeks after the end of the war, the London Daily Express broke the story of James’s wartime leading role. European and North American newspapers ran brief items on the story, but it generated only mild interest; much of the world was fed up with war and looked forward to moving on.

Clifton James stayed in the army until he was demobilized in June 1946. He returned to Australia and, like so many veterans trading in their uniforms for civilian suits, struggled to find a place for himself. That same year, he wrote a book about his exploits called The Great Deception, but the manuscript sat with the British War Office for “vetting” with no given timeframe nor explanation.

The following year, local newspapers reported that he had applied for unemployment benefits. In a short article titled “Monty’s Double Broke,” James claimed that he had been able to acquire only three days’ work as an actor. Producers, he explained, were hesitant to cast him in plays, as audiences were only interested in “seeing Monty,” not seeing James in another role. “It seemed that fame could be of the wrong sort,” he mused. “No actor ever got more publicity than I did. Managers and others rushed to greet me, set me on a pedestal for all to see—but none of them thought of offering me a job.”

Granted a small government pension, James was compelled to secure another source of income. Agreeing to reprise his most famous role, James toured and played Monty to amused crowds across Australia and England before planning a similar trip to South Africa. “I know it is cheap and at first I resisted offers to do it, but I must eat and think of my wife and two schoolboy sons,” he said in 1947.

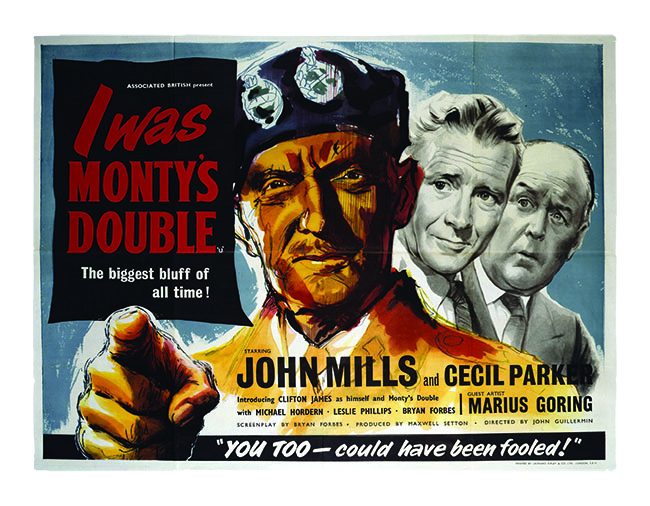

In 1954, eight years after James submitted his memoir to the War Office, the manuscript finally received the go-ahead and was published as I Was Monty’s Double. The book was successful, and Hollywood soon came knocking. The 1958 film adaptation featured James—both as himself and as Montgomery—and took several liberties with the story, going so far as to gin up a German plot to assassinate him.

In the wake of renewed interest in his story, James appeared on the American television game show To Tell the Truth in January 1959. It was his last screen appearance. On May 8, 1963, on the 18th anniversary of V-E Day, M. E. Clifton James died at the age of 65. Upon hearing the news, Bernard Montgomery said: “He performed a very useful purpose at a very dark time of the war. What he did completely fooled the Germans.”

BUT DID IT? It is difficult to evaluate James’s contribution alone, and we may never know for certain. German agents did indeed report Montgomery’s arrival in Gibraltar to their stations in Madrid and Berlin. In his 2011 book, Operation Fortitude: The Story of the Spies and the Spy Operation That Saved D-Day, historian Joshua Levine contends that the Germans were so overwhelmed by conflicting intelligence about the impending invasion—the work of at least 30 separate deception operations—that Monty’s apparent visit to the Mediterranean was but a tiny scrap of information amid countless reports of varying veracity: one sheet of paper in a stack of hundreds.

However, the overall deception campaign did succeed, and Operation Overlord caught the Germans by surprise on the morning of June 6. By those terms, Clifton James’s performance helped sell the plausibility of the whole show—and it was a roaring success. ✯

This story was originally published in the February 2019 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.