Just before 6 o’clock on the morning of April 19, 1956, Lionel Crabb, an expert British diver, quietly left the Sally Port Inn in Portsmouth, England, accompanied by his minder, a tall, slim American going by the name of Bernard Smith. The two men made their way to HMS Vernon, a red-brick dockside compound of the Royal Navy. There, in the crisp morning mist, they met up with Lieutenant George Franklin, a Royal Navy diving officer who, two nights earlier, had agreed to act as Crabb’s helper and dresser in a clandestine mission arranged by MI6, the British Secret Intelligence Service.

Ostensibly, the plan was for Crabb to dive beneath the Soviet gun cruiser Ordzhonikidze, which was temporarily docked in Portsmouth Harbor, to photograph its keel, propellers, and rudder. The British, then embroiled in the uneasy espionage of the Cold War, were keen to understand the underwater workings of Soviet vessels and the antisubmarine warfare equipment they carried beneath their hulls.

The Ordzhonikidze had arrived in Portsmouth Harbor a day earlier amid much fanfare. On board were the two most important men in the Soviet Union: Nikolai Bulganin, the pragmatic, smartly dressed premier and minister of defense, and Nikita Khrushchev, the energetic, unkempt first secretary of the Communist Party. They had come to the UK on a goodwill mission as guests of the British government. Eager to deflect attention from a crisis that was brewing ominously with Egypt in the Suez Canal region, Anthony Eden, Britain’s prime minister, was on a Cold War charm offensive. The last thing he wanted was scandal. Both of the UK’s security agencies, MI5 and MI6, were told that spying was at least temporarily out of the question.

Someone, though, clearly hadn’t gotten the message.

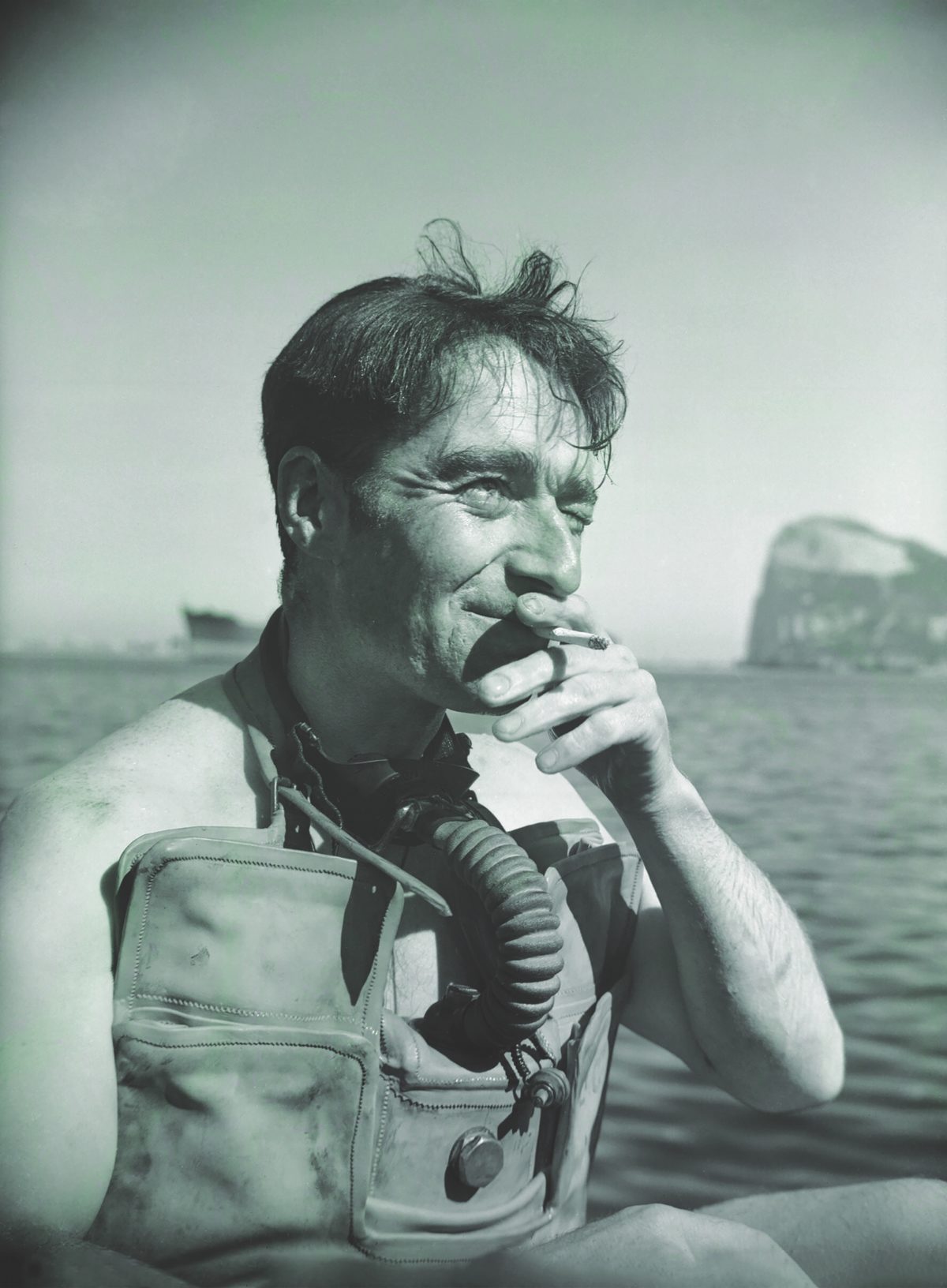

With two policemen escorting them, Franklin and Crabb made their way to the dockside, where a small launch had been procured to get them to within easy swimming distance of the Ordzhonikidze. As Franklin adjusted Crabb’s Heinke frogman suit, the diver settled his nerves with a cigarette on the gunwale before hitting the water just before 7 o’clock and descending into the murky depths. Despite his exemplary wartime service, Crabb, at 47, was not a fit man. A prodigious drinker and smoker, he had supposedly downed five double whiskies the night before on a boozy pub crawl in the nearby town of Havant—not exactly the ideal preparation for such a high-stakes mission.

Crabb surfaced less than 20 minutes later, complaining about the cold and lack of visibility, and asked for an extra pound of ballast. Franklin obliged, attaching a weight to Crabb’s equipment. After checking Crabb’s oxygen levels, Franklin watched him resubmerge and sat down again to wait. And wait. And wait.

Around 9:15 a.m., Franklin realized that something was amiss. Nearly two hours had passed since Crabb had disappeared with little more than 90 minutes of oxygen in his tank. After making a cursory search of the harbor, he aborted the mission and alerted Smith, who was waiting on the shoreline, that Crabb was missing. There was no alarm or police search. Instead, Smith, who had booked into the Sally Port Inn with Crabb two days earlier, coolly paid the bill and hastened back to London, taking the diver’s personal effects with him. Crabb was never seen again.

Thus began a 65-year mystery surrounding the disappearance of Lionel “Buster” Crabb, a real-life spy story filled with intrigue and conjecture that has given birth to assorted conspiracy theories and inspired a host of books.

Six decades after the events, numerous questions re-main unanswered. What was Crabb doing on that fateful day? Who was he working for? What happened to him? And why has the British government still not declassified important evidence relating to the case?

Maverick, loose cannon, and nonconformist are all words that have been used to describe Lionel Kenneth Phillip Crabb. Born in London in 1909, Crabb had a modest and unremarkable upbringing. Diving wasn’t a natural calling. Even at the height of his wartime heroics, Crabb was neither a star athlete nor a strong swimmer. But he was brave, audacious, and adaptable in difficult situations. After training as a navy cadet, he became a merchant seaman, transferring at the beginning of World War II to the Royal Navy, where he gravitated toward the highly specialized field of bomb disposal.

Crabb was based in Gibraltar in 1942, when Italian saboteurs were causing havoc by fixing limpet mines to the hulls of British ships. It was Crabb’s job to defuse the explosives. He took to the task with casual aplomb, learning to dive with equipment salvaged from two deceased Italian frogmen. In 1945 he transferred to northern Italy, where he was assigned to clear Venice Harbor of unexploded Ger-man ordnance, and then to the Middle East, where Zionist rebels were attacking British ships. It was difficult and dangerous work but, spurred by a vigorous sense of patriotism and duty, Crabb quickly made a name for himself.

By the mid-1950s, Commander Crabb was a war hero with an Order of the British Empire and a George Medal. He had even acquired the sobriquet “Buster” after Buster Crabbe, the Hollywood actor and former Olympic swimmer. Something of an eccentric, he favored tweed suits, wore a monocle in the style of an English gent, and brandished a silver swordstick with a crab emblazoned on its handle. Rumors swirled that he had a rubber fetish and liked to sit down to dinner in his frogman suit. Despite his dandy demeanor, Crabb battled depression, an illness he buried in drink, gambling, and womanizing.

After retiring from the Royal Navy in 1947, Crabb worked as a diver for hire, exploring sunken Spanish galleons off the Scottish coast and running a rescue mission to a stricken submarine in the Thames Estuary in 1950. He was probably recruited by MI6 in the mid-1950s, and in 1955 the Admiralty hired him to dive beneath the Soviet cruiser Sverdlov when it was docked in Portsmouth to look at its distinctive turning mechanism. The mission went without major incident, but next time he wouldn’t be so lucky.

When the dust had settled in Portsmouth Harbor on that chilly April day in 1956, it became clear that Lieutenant Franklin may not have been the last person to see Crabb alive. At around 8 o’clock the same morning, three Russian seamen allegedly spotted a diver in the water alongside the Ordzhonikidze. Over an after-dinner coffee later that evening, Admiral Pavel G. Kotov, the Soviet ship’s commander, mentioned the sighting to Admiral Sir Robert Lindsay Burnett, his counterpart at the Portsmouth Naval Base. He wasn’t making an official complaint (as yet) but, puzzled by the presence of a mysterious frogman near his ship, Kotov wanted to know what was going on.

Fearing repercussions while the Soviet delegation was still in Britain on its goodwill mission, MI6 went straight into damage control mode, hurriedly preparing an elaborate coverup. On April 21, 1956, a police officer went to the reception desk of the Sally Port Inn and ripped three pages out of its guest registry, expunging any record that the diver and his handler, the mysterious Mr. Smith, had stayed there. Then, on April 27, the Admiralty put out a statement claiming that Crabb had gone missing after taking part in trials of underwater equipment in Stokes Bay, several miles west of Portsmouth’s docks. It was a thinly veiled lie.

For the outside world, these details clearly weren’t adding up. Crabb’s family was anxious for information about Crabb, and journalists thought they smelled a rat.

Prime Minister Anthony Eden, meanwhile, was seething. Unaware of MI6’s involvement in the Crabb affair until May 4, he was forced to field awkward questions in Parliament while parrying inquiries from an increasingly suspicious press. Disclosing the nature of Crabb’s disappearance was not in the public interest, he claimed: MI6’s action had transpired “without the authority or the knowledge of Her Majesty’s Ministers,” and “appropriate disciplinary steps” would be taken. While Eden’s public demeanor was measured, his private mood was apoplectic. The secret service had explicitly gone against his orders. Heads would roll, including that of MI6 chief John Sinclair, who was promptly forced to retire. The press had a field day.

The Russians weren’t happy either. Pravda, the official Communist Party daily, called the episode “a shameful operation of underwater espionage directed against those who come to the country on a friendly visit.” The Soviet government filed an official protest, and Britain was forced to make a humiliating apology. Eden’s Cold War bridge building had been disrupted by an earthquake.

As time passed, relations healed. Eden resigned over the Suez debacle in January 1957, to be replaced by Harold Macmillan. Interest in the Crabb affair seemed to be on the wane when, in June 1957, a fisherman named John Randall found a headless, handless corpse in a Heinke diving suit entangled in his fishing nets in Chichester Harbor—eight miles east of Portsmouth’s dockyard. Rather than ending the debate, the incident served to intensify it. Lacking essential body parts, the corpse proved difficult to identify. Neither Crabb’s mother nor his wartime diving partner, Sydney Knowles, could categorically say it was Crabb. Notwithstanding, the coroner ultimately declared that there was enough evidence to suggest the body was Crabb’s. Some believed him; many didn’t.

The remains were laid to rest in Milton Cemetery in Portsmouth, although Crabb’s mother still refused to say they were her son’s. While the discovery of a corpse ensured that the celebrated commander received a proper burial, it didn’t snuff out the theories about his disappearance, which were piling up like photofits on a police crime board.

The simplest explanation was that Crabb’s death was an accident, the result of an unfortunate equipment mishap or possibly a heart attack. The wheezing middle-aged diver was notoriously unfit at the time of the Ordzhonikidze mission, and his affinity for drink and high-tar Turkish cigarettes was well known. This line of reasoning, however, underestimated Crabb’s ability as a frogman and ignored the fact that Portsmouth’s sheltered docks weren’t particularly difficult diving territory for someone of his experience and skill. Additionally, if Crabb had died of natural causes, why the headless corpse, the lack of a proper missing person report, and the intense government coverup?

Another regularly cited theory suggests that Crabb was assassinated by the Russians. This claim was widely propagated in the 1972 book Operation Portland, written by convicted spy Harry Houghton, who purported that Crabb had been taken on board the Ordzhonikidze and killed after being interrogated. A similar, perhaps slightly more credible scenario was advanced in 1990 by Joseph Zwerkin, a former Soviet naval intelligence agent, who maintained that a Russian sniper on the ship’s deck had spotted the frogman in the water and shot him..

In 2007, a 74-year-old retired Russian sailor named Eduard Koltsov came out of the woodwork, declaring on a television documentary that he had cut Crabb’s throat after he saw the diver attaching a mine to the hull of the Ordzhonikidze. The much-belated claim was widely dismissed as far-fetched. The idea that Crabb, with the support of MI6, was trying to blow up a Russian ship on a goodwill mission in British waters made no sense and would have been counterproductive in the extreme.

Others have speculated that instead of killing Crabb, the Russians took him—voluntarily or involuntarily—back to the Soviet Union. Cold War spying was at its height in the 1950s. Two British diplomats, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, had defected to the Soviet Union several years earlier. It was probable that Crabb had already met others in British spy circles including Kim Philby and Anthony Blunt, both of whom were later unmasked as Soviet double agents.

In his 1960 book Frogman Extraordinary, J. Bernard Hutton alleged that sources in the USSR had told him that Crabb was working as a diving officer in the Russian navy and that the Russians had dropped an anonymous handless, headless corpse into Chichester Harbor as a cover. The book even included a photograph of a man it claimed was Crabb—alive.

This defection story was corroborated by Patricia Rose, Crabb’s fiancée at the time of his disappearance. In a 1974 newspaper article, Rose declared that Crabb had successfully gone to the Soviet Union and was working as a double agent, training Russian frogmen in the Black Sea. She even claimed that Crabb had been in touch with her through intermediaries who had told her that he was homesick.

Over time, rumors that Crabb was still alive became as frequent as stories of Elvis sightings. There were reports that he was languishing in Moscow’s Lefortovo prison, that he had been tortured and brainwashed, that he was serving in the Soviet navy as Lieutenant Lev Lvovich Korablov. But no solid evidence was ever presented to back up the claims.

In 2006, the story took the spotlight off the Russians and aimed it at the British when Crabb’s old diving partner, Sydney Knowles, contacted author Tim Binding, who had written a fictionalized account of the Crabb affair the previous year. Knowles, who had known Crabb since his Gibraltar days, claimed that the Ordzhonikidze mission had been a setup, and that a fellow frogman hired by MI5, the UK’s domestic security agency, had eliminated the diver to prevent him from defecting to the USSR.

According to Knowles, Crabb had expressed bitterness about the way the navy had treated him in retirement and had subsequently begun fraternizing with the likes of Anthony Blunt and other Soviet sympathizers. Defection, he implied, had become a serious consideration.

Knowles’s allegations, although shocking, were interesting in that they came from someone who was professionally close to Crabb. Nevertheless, it’s difficult to imagine how Crabb, a celebrated war hero who had put his life on the line for his country numerous times, would suddenly flip and contemplate treason. In reality, most of Britain’s Cold War spy ring had been recruited young, when they were still in school, before Joseph Stalin’s grisly crimes had become fully apparent.

For 65 years, the Crabb affair has filled newspapers, books, and public debate, but it has yet to deliver an adequate epilogue. Nevertheless, touched by a mixture of heroism and tragedy, it has spawned a lucrative myth. Indeed, the adventurous and sometimes louche life of Crabb, who worked under Ian Fleming in naval intelligence during World War II, is often cited as one of the inspirations for the character of James Bond. His diving exploits were subsequently fictionalized in Fleming’s 1961 novel Thunderball.

The trickle of documents released by British authorities over the years has thrown some light on a raft of government blunders, high-level misunderstandings, and messy coverups, but fundamental questions linger: What happened to Crabb on April 19, 1956, and was it really his mutilated body that washed up near Chichester in 1957?

The truth, however, could be a long time coming. In 1987, in a mysterious plot twist, the British government added 70 years to its standard 30-year declassification rule on files related to the Crabb affair. For the full story, the world will have to wait at least until 2056. MHQ

Brendan Sainsbury, a freelance travel writer, is originally from Hampshire in the United Kingdom and now lives near Vancouver, Canada.