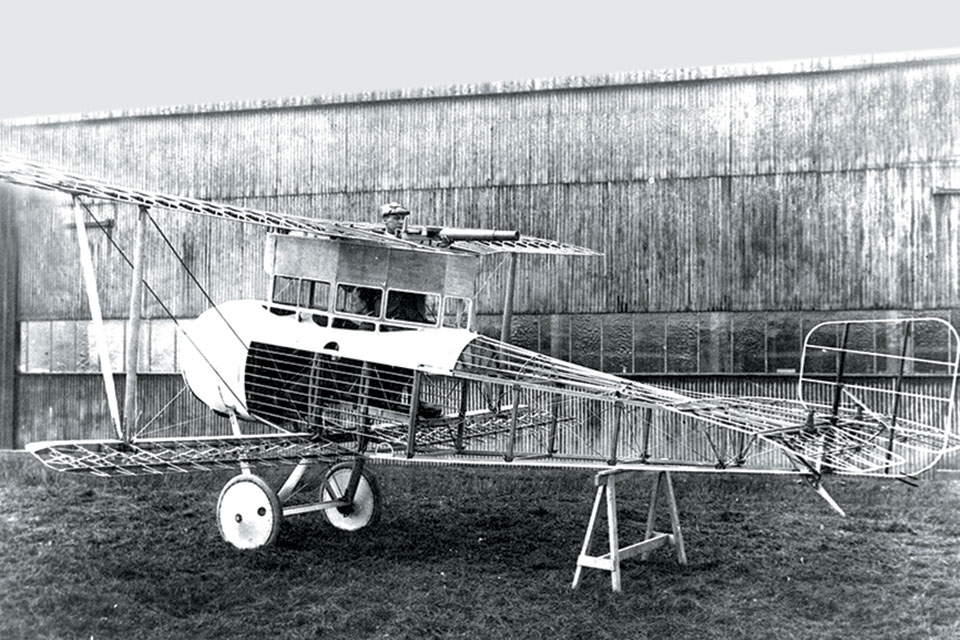

The Sage Type 2 fighter’s elegant enclosed cockpit set it apart from other early two-seaters.

When World War I began, few aircraft existed that had been specifically designed for military use. Of those, most were intended for reconnaissance, and little thought had been given to arming them. It wasn’t long, however, before pilots recognized the necessity of equipping their airplanes for combat. They began by attacking enemy reconnaissance planes operating over their territory, as well as by protecting their own recon planes in enemy airspace.

One of Britain’s first successful military mounts was the Bristol Scout, a compact single-seat tractor biplane. Designed by Frank Barnwell and first flown in February 1914, the Scout had originally been conceived as a racer. But it established the design formula that would eventually dominate WWI single-seat fighter development to such an extent that the configuration would become generically known as the “scout plane.”

The Bristol Scout could reach 95 mph on the meager 80 hp generated by its Le Rhône rotary engine. Despite its excellent flying qualities, the plane exhibited a number of disadvantages as a fighter. Pilot Cecil Lewis praised its handling characteristics, but recalled that the Scout was “so small even an average man has to be eased in with a shoehorn” and “so narrow that my knees prevented any lateral movement of the stick; so short that I can hardly move the rudder.” In addition, the pilot was seated between the upper and lower wings, which interfered with his view. Worse still, the Bristol Scout hadn’t been designed to carry a machine gun, and consequently no adequate method was ever devised to install one.

When Clifford W. Tinson, who had served as assistant designer under Frank Barnwell at Bristol, became the chief designer at Sage Aircraft in 1915, he brought with him his experience working on the Scout. He also brought some very original ideas on what a successful fighter plane should be. The result was the Sage Type 2 two-seater, one of the most unusual combat planes of WWI and among the first aircraft with an enclosed cabin.

With a span of only 22 feet 2 inches and a mere 21 feet 1 inch long, the Sage was extremely compact, especially for a two-seater. Its tail surfaces and landing gear displayed a distinct family resemblance to the Bristol Scout. The large propeller spinner and closely cowled rotary engine were also reminiscent of the engine installations seen on some of the little Bristols. Aside from those similarities, however, the Sage Type 2 was strikingly different from its predecessor.

The Sage’s wings emulated the French Nieuport rather than the British Bristol design practice, in that they were of sesquiplane, or “1½,” layout. The two-spar upper wing was of very broad chord, while the single-spar lower wing was exceedingly narrow. That wing configuration had contributed to the conspicuous success of the Nieuport 11, 16 and 17 scouts in air-to-air combat. In addition to providing excellent maneuverability, the narrow chord of the Nieuports’ lower wings gave pilots an improved downward view.

Tinson’s experience with the Bristol Scout had obviously convinced him that a tractor engine layout offered superior performance to that of a pusher. However, the lack of a practical synchronizing gear meant that a method would have to be found to enable a machine gun to fire ahead without striking the propeller. Tinson, again influenced by Nieuport, devised a novel solution: He raised the top wing above the arc of the propeller and positioned the gunner above the wing, where his single .303-caliber Lewis gun had an unobstructed field of fire in all directions.

The pilot was seated ahead of and below the gunner, within an enclosed cabin built between the upper wing and the fuselage. The cabin featured transparent panels all around, affording the pilot what Tinson believed to be “a view equal to that he would have obtained in a similar machine unenclosed.” In addition, the pilot had sliding windows on either side, which he could open up in order to stick his head out of the cabin for a better downward view. Just how the crew gained access to the interior of the cabin is not entirely clear from surviving photos, but presumably there must have been some sort of door or hatch provided for the purpose. The cabin’s elegant, white-painted interior quickly earned the little aircraft its strictly unofficial nickname the “Flying Boudoir.”

One direction in which the pilot could not see, however, was upward, since the fuel tank was mounted directly above his head. Tinson believed that placing the fuel tank “where no Boche would think of finding it” would reduce its likelihood of being hit, and that if it was hit the fuel “would run away clear of the course of fire.” The fact that the leaking fuel would “run away clear” all over the unfortunate pilot does not seem to have concerned the designer. But the fuel tank’s separation from the engine might have been a blessing in disguise, since the engine designated for the Sage, a 100-hp Gnome Monosoupape, demonstrated a disconcerting tendency to catch fire when starting and stopping.

Among the most critical considerations for combat success in a two-seater was close cooperation between the pilot and gunner. The crews of some otherwise satisfactory aircraft, such as the Salmson 2A2 and de Havilland D.H.4, found themselves at a disadvantage in aerial combat because the distance between the pilot and gunner made it difficult for them to communicate. Two-seaters in which the crewmen were situated in close proximity to each other, such as the Bristol F.2B and Halberstadt CL.II, earned formidable reputations.

With the gunner’s head and shoulders protruding above the upper wing and the pilot seated inside the cabin, one might think that cooperation between the Sage’s aircrew was difficult. However, Tinson claimed to have devised an ingenious solution to that problem: “We provided an indicator in the pilot’s compartment, which was worked from the gun ring so that if an enemy appeared in some part of the sky which was blanked off to the pilot, the gunner, standing up in back where he could see everything from horizon upwards, could direct the pilot to change his course accordingly.”

Development of the Sage Type 2, which was intended for the Royal Naval Air Service, began early in 1916, but the plane was not flown until August 10. Completion of the prototype had been delayed mostly because the delivery of its Gnome engine had been held up by the war. Even by the standards of 1916, a 100-hp engine was regarded as minimal for a two-seater, but it was the best the Admiralty could provide under the circumstances. Despite its relatively low-powered engine, the Sage Type 2 demonstrated a sparkling performance by the standards of the day. Weighing in at only 1,546 pounds fully loaded, the tiny two-seater could do 112 mph at ground level and 109 mph at 10,000 feet, to which height it could climb in 14 minutes 45 seconds. It had an endurance of 2½ hours and a ceiling of 16,000 feet.

Although the Sage Type 2 impressed those who initially witnessed its testing, development ended abruptly after the prototype crashed on September 20. Neither the pilot nor the designer, who happened to be in the rear cockpit when the plane crashed, was injured. It was later ascertained that the crash resulted from the collapse of the rudderpost, attributed to a flaw in the manufacture of that individual component rather than to any inherent design fault.

Nevertheless, technological advances had been so rapid that the Sage Type 2 would have been obsolete by the time it appeared over the Western Front. By the fall of 1916, practical gun synchronizing gears had been perfected, as had engines developing well over twice the power of the troublesome Gnome rotary. Powerful and versatile new two-seaters such as the Sopwith 1½-Strutter, de Havilland D.H.4 and Bristol F.2B were coming on line—aircraft with more than twice the power and armament of the diminutive Sage.

As for Clifford Tinson, he thought his Flying Boudoir was a success. He wrote that he believed the concept would be resurrected at “a time when comfort in flying will be an important consideration.” Considering the subsequent popularity of small cabin planes in general aviation, perhaps he was right.

Originally published in the March 2009 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.