The people of Paris were nervous, and with good reason. In the days since the August 3, 1914, declaration of war between France and Germany, the Germans had advanced rapidly through Belgium and northern France, and their First Army had reached the Marne River, just 30 miles east of Paris. Parisians could hear the distant rumble of artillery, feeding their fears. Their morale was further depressed when the French government and many wealthy families fled the city and headed southwest to Bordeaux.

To prepare the French capital for a siege, General Joseph Galliéni commandeered every taxi in Paris and rushed all available reinforcements to the front in what was called the “taxi cab army.” Many anxious residents remembered the German victory in the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War, and the occupation of Paris.

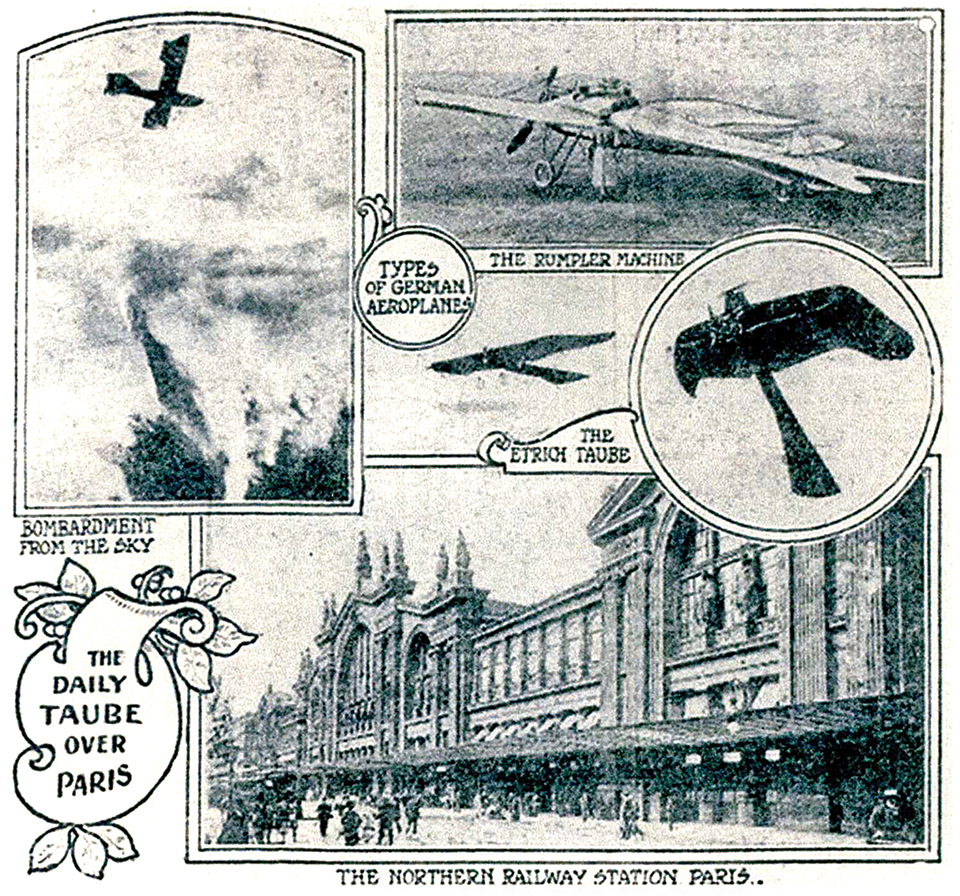

Just after noon on August 30, Parisians heard something above them and looked up to see a strange airplane shaped like a giant bird, with German crosses under the wings. Some recognized it as a Taube (dove), and people watched with curiosity as its observer dropped four small bombs by hand from about 6,000 feet. The first bomb reportedly exploded near the Gare de L’Est (or Nord) railway station, the second in a courtyard at 107 Quai Valmy. The third landed in the street at 66 Rue des Marais, and the fourth bomb broke through a skylight in the Rue des Recollets but failed to explode. One woman was reported killed and four people wounded.

As it turned out, the bombs were not as alarming to the populace as a small object with a streamer that was dropped into a street, where it was retrieved and taken to the gendarmes. Inside the sand-filled pouch were a few propaganda leaflets and a message in French that read: “The German army is at the gates of Paris. There is nothing for you to do but surrender. Lt. von Hiddessen.” The message made the front pages of the next day’s Parisian newspapers.

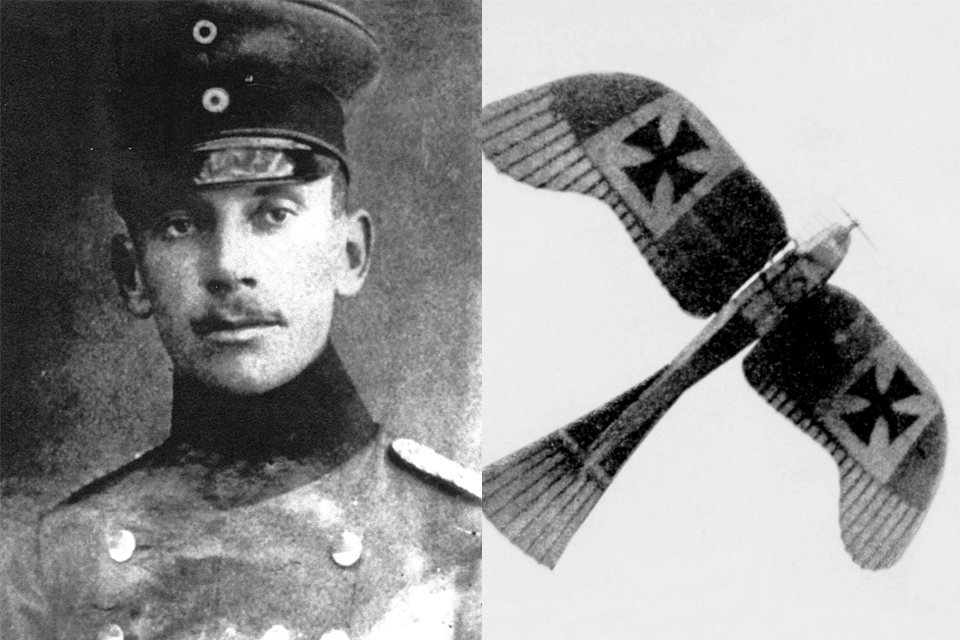

Ferdinand von Hiddessen, the pilot in this first raid by an airplane on a national capital, had joined the German army and been commissioned a 2nd lieutenant in 1908. In 1910 Leutnant von Hiddessen learned to fly at the August Euler School and received pilot license No. 47. He participated in army maneuvers and entered several aviation contests, winning numerous prizes. In June 1912 he took part in Germany’s first airmail flight, and later collected weather data for meteorological research.

When war broke out von Hiddessen was serving in Feldflieger Abteilung (field flying detachment) 11. Assigned to an army corps for observation and reconnaissance, it was equipped with six license-produced Rumpler Taube monoplanes. The birdlike Taube, designed in 1910 by Igo Etrich, featured wing-warping lateral control and a 100-hp Mercedes or Daimler engine that gave it a top speed of 75 mph.

Von Hiddessen’s commander had selected him for the Paris mission because of his extensive flying experience. After von Hiddessen and his observer dropped their payload, their main concern was the return flight. They were worried that the Taube would run out of fuel during the 2½-hour mission, but they landed safely at their field at Saint-Quentin in northern France.

Von Hiddessen returned to Paris at about 5 p.m. the next day and dropped two more small bombs, with one failing to explode. On September 1 another Taube dropped six bombs, killing three people and wounding 16. The following day three planes were reported over the city around 5 p.m., and Parisians began referring to the interlopers as the “Five O’clock Taubes.” Newspapers and city officials urged residents to stay indoors during the air raids, but many remained in the streets and cafes watching the planes through binoculars and opera glasses. The raids then temporarily ceased, as the German aircraft were needed for reconnaissance at the front on September 6 with the beginning of the Battle of the Marne. German raiders returned on the 8th, but no bombs were dropped. A few subsequent raids caused little damage.

Even though the first air raids on Paris accomplished little, and the initial panic they caused quickly dissolved, they set an important precedent as an early aerial example of psychological warfare. They also demonstrated the future potential of air power.

Although Paris was within the operating zone of tactical aircraft at that time, the air raids were not directly in support of German ground forces. After fierce fighting in the Battle of the Marne, the Germans withdrew to a line on the Aisne River.

Recommended for you

The Germans launched a serious strategic bombing campaign in January 1915 with raids on southern England by Zeppelin airships. In May 1917 raids began employing twin-engine Gotha bombers and multiengine Riesenflugzeuge (giant airplanes), continuing until May 1918. Although the damage and casualty figures were minimal by later standards, the raids had a noticeable psychological impact on the British public. More important, they forced the diversion of large numbers of pursuit planes, anti-aircraft guns and searchlights from the Western Front.

After the First Battle of the Marne, von Hiddessen performed observation work until he was shot down over Verdun in 1915. He recovered from serious wounds and remained in a French prisoner of war camp until hostilities ended with the armistice on November 11, 1918. Discharged from the army with the rank of cavalry captain, he became a farmer.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The postwar years was a time of great difficulty in Germany, with runaway inflation and widespread unemployment, which saw many disgruntled Germans turning to radical political parties. Von Hiddessen joined the Nazi Party in the 1920s, and from 1933 commanded an SA (Sturm Abteilung) unit. In 1937 he transferred to the newly founded NSFK (Nationalsozialistisches Fliegerkorps), and was later honored for his organizational work in training fledgling pilots. After the outbreak of World War II, he was commissioned a captain in the Luftwaffe in early 1940. The end of the war saw him interned for more than three years. He lived his last years quietly on a small farm in the Black Forest, and died at Neustadt in January 1971.

This article originally appeared in the November 2018 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!