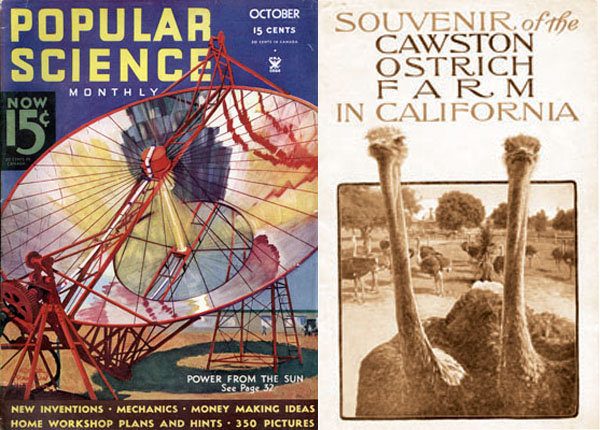

Edwin Cawston’s ostrich farm in South Pasadena, Calif., was a bona fide tourist attraction. Cawston had been breeding the birds since 1886 to cash in on the lucrative trade in feathers for women’s fashion. In 1901, Cawston met up with Aubrey Eneas, an inventor who needed a sunny, public place to demonstrate his latest machine: a motor powered by solar energy. Cawston bought one of Eneas’ 8,300-pound glass-and-steel contraptions to pump water for the arid ostrich farm. It worked. Eneas’ parabolic reflector—33 feet at its widest point and covered with 1,788 pieces of mirrored glass—heated water in a metal boiler at the center of the reflector. Steam was then routed from the boiler to an engine that pumped 1,400 gallons of water a minute from a deep well. The first successful commercial use of solar power seemed primed to launch an energy revolution, but Eneas’ reflectors fared poorly in other parts of the Southwest, where fierce storms tore them to pieces. With a price tag of $2,500, the reflectors were well beyond the means of most, and cheap oil soon became the fuel of the future. Eneas gave up on solar and declared bankruptcy around 1910. A year later, Cawston sold his farm for $1.25 million, but the innovative solar motor continued to pump water for the ostriches until World War I, when the reflector’s metal was needed for the war effort.

1835 William Austin Burt designs a solar compass when iron ore deposits in the upper Midwest throw off magnetic compass readings

1948 MIT scientist Maria Telkes develops solar panels capable of heating an entire house

1958 International Rectifier Corporation refurbishes a 1912 Baker electric car and powers it with 10,000 solar cells mounted on a rooftop panel

1981 Solar Challenger sets a record for manned, solar-powered flight with a 163-mile, 5-hour trip