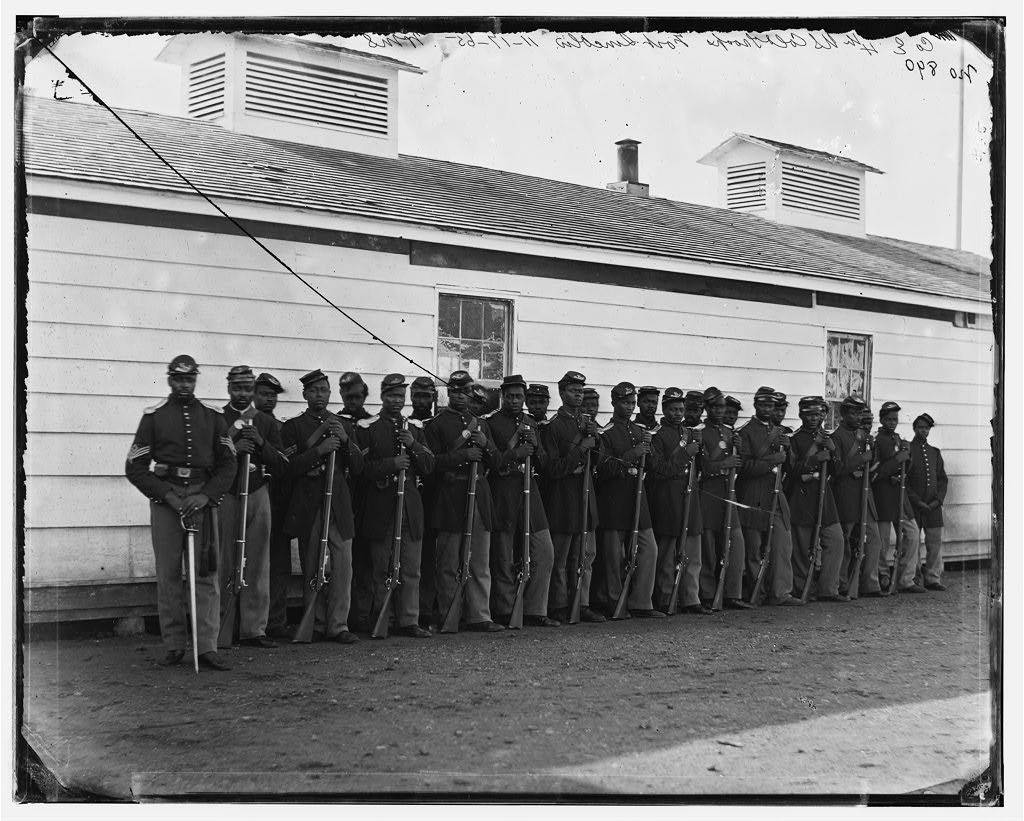

Under the leadership of Eleanor Holmes Norton and Cory Booker, the U.S. Congress has begun debating the possibility of awarding the Congressional Gold Medal to the nearly 200,000 Black people who served in the U.S. military service during the Civil War. Their efforts reinforce that Black Civil War military service, even 100 plus years ago, deserves commemorating and honoring. At the same time, the well-deserved, posthumous award provides a way to include their sacrifices to the ongoing — and often contentious — debates about Civil War public memory.

After the Civil War officially ended on April 9, 1865, many Black veterans and their families entered a new battleground: the public memory of the war. For example, one need only look at the lack of postwar public ceremonies for Black New York regiments. More specifically, even though the 20th United States Colored Infantry, or USCI, Regiment previously received a grandiose deployment military procession (in 1864) which garnered national attention as Black men, in U.S. Army uniforms, marched down the same New York City streets where the Draft Riots occurred seven months earlier. But after the 20th USCI mustered out in October of 1865, they did not get a return event.

Conversely, multiple white New York regiments — including the 63rd New York Infantry Regiment, received a well-attended celebration upon returning to New York City on July 4, 1865. Unfortunately for Black veterans and their kin, the lack of public acknowledgment, in the form of mustering out processions, highlighted that some members of their local communities no longer prioritized honoring their service. It also meant that the earlier promises made by individuals, such as Union League Club of New York President John Jay, that the sacrifices of Black soldiers and their families would never be forgotten became hollow in a little over a year.

Nearly a generation later, some Black veterans decided to become historians to confront whites — scholars and non-academics — for attempting to erase Black military service from public conversations systematically. For instance, both the Lost Cause myth and white reconciliatory rhetoric promoted a historical narrative that framed the Civil War as a “white man’s war,” excluding the nearly 200,000 Black men who served in the U.S. Army and Navy during the conflict. As a result, five Black Civil War veterans — Joseph T. Wilson, Isaac J. Hill, Alexander Heritage Newton, William J. Simmons, and George Washington Williams — used their knowledge, skills, and passion for fighting for their inclusion in the historical memory of the Civil War and became historians. And their collective scholarship, which published between the 1880s and 1890s, provided detailed accounts of Black military service, including documenting multiple military engagements against Confederate forces, to illustrate undeniable truths. Black men fought in the Civil War, and they, like their white counterparts, deserved to be remembered.

The families of numerous Black Civil War soldiers also fought their own battles for inclusion in historical memory. Multiple family members across numerous generations provided economic and emotional support for surviving veterans. As the veterans aged, their kin often provided informal medical care. Some family members attempted to assist in helping veterans navigate the highly complex and bureaucratic Civil War pension application process. And familial support became even more complicated, unfortunately, as many pension agents — who were often white men — routinely denied Black pension applicants primarily on the conviction that they were “untrustworthy.” Even so, their kin never stopped fighting social welfare aid (in the form of pensions).

Many Black families remained resolute in their demands to have their lives remembered in federal government documents after the Civil War ended. For example, Edmonia (the daughter of deceased 6th USCI Regiment soldier William Woodson) wrote Eleanor Roosevelt in 1939. Edmonia pleaded with the First Lady for assistance with her mother’s Widow’s Pension application. Rather than ignore the request, Eleanor demanded representatives in the Veterans Affairs investigate the pension case immediately and provide a definitive answer. Edmonia’s case, while unique, illustrates that Black families — across multiple generations — expressed that their family had not moved on from the Civil War. Their correspondence reveals that the First Lady refused to legitimize the Lost Cause myth by answering Edmonia’s request.

The potential Congressional Gold Medal is long overdue for Black Civil War soldiers. Undoubtedly, the award is also a way to honor their lives and the lives of their families who supported the soldiers. It is also further proof that the remembrance of the Civil War can continue becoming more inclusive if we hope to, more accurately, honor their legacies.

Originally published by Military Times, our sister publication.