LAURA INGALLS was planning her most daring aviation stunt yet. The famous pilot intended to reveal her ambitions to her friend Sylvia Comfort over dinner at a Los Angeles restaurant in July 1941. But first, Ingalls swore the young woman to secrecy. “I have all the confidence in the world in you,” Ingalls told Comfort that night. “I know if I told this to the wrong person, I would get into trouble.”

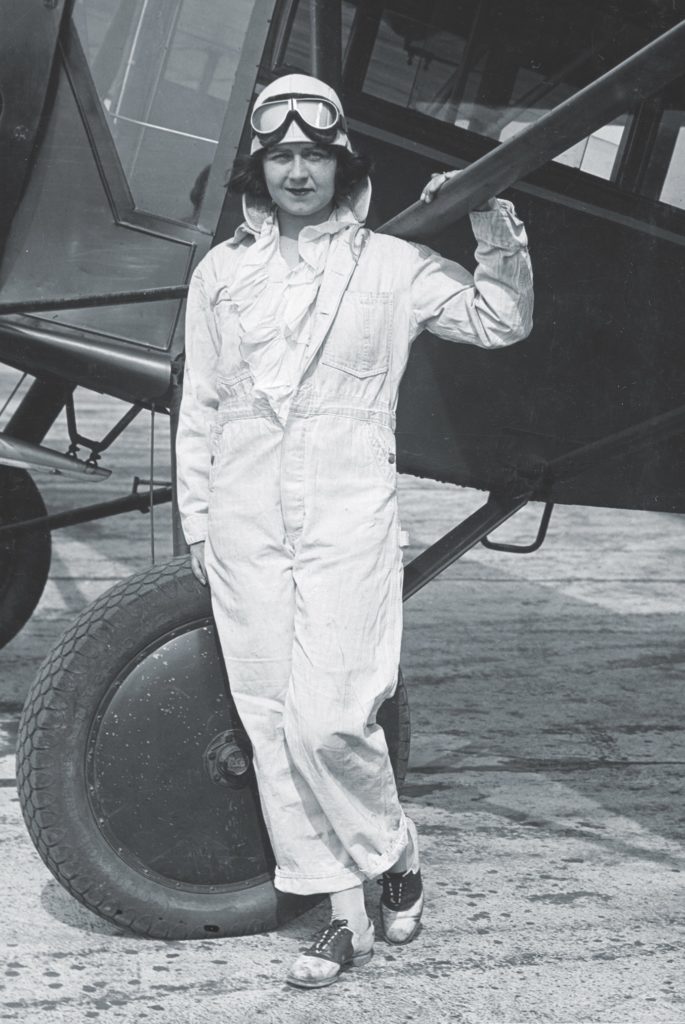

It would take a lot to top Ingalls’s previous exploits. Through the 1930s, she had made a name for herself as a fearless flier who had little regard for the restrictions that society and gravity placed upon a woman pilot. At the start of the decade, she had set the women’s record for consecutive loops in an airplane, turning 344 cartwheels over St. Louis, and then, three weeks later, broke her own record with 980 loop-the-loops in the Oklahoma skies. She continued her dizzying rise to fame in 1930 with a record-setting 714 barrel rolls and the first round-trip transcontinental flight by a woman. Over the next several years, she and Amelia Earhart battled for the distinction of being the fastest woman pilot to fly from coast to coast, but Ingalls’s solo flight to South America in 1934 remained unrivaled.

She flew 17,000 miles from New York to Santiago, Chile, and back again, skimming over the Andes at 18,000 feet. The feat earned her an aviation trophy for outstanding flying that year by an American pilot.

It seemed nothing could ground Laura Ingalls—until war broke out. “Since the Army, Navy and Airlines have recently so absorbed aviation activity, there is literally no chance for a woman to secure a job in flying,” Ingalls wrote in 1939. “I need such a job if I wish to continue to fly—which I do.” Her love of piloting had nearly bankrupted her, and she had to find financial backing to stay in the air.

Ingalls addressed her plea to J. Edgar Hoover at the Federal Bureau of Investigation. “Could you by any chance use in your organization the services of a woman flyer?,” she asked. “It occurred to me that in some way I might be able to work for you through the medium of my airplane and perhaps serve my country as well—something I love to do;—even though I am a woman.” When her first offer was refused, Ingalls wrote again: “It seems inconceivable there is nothing which a woman of intelligence, education and background could do to help safeguard the interests of this country in the present crisis.” To this, the FBI director responded bluntly, “Appointment is limited to male applicants.”

But Ingalls paid no more heed to Hoover than she had to the flight instructors she encountered who, she recalled, would “jolly a girl along instead of taking her work seriously.” By the time Hoover’s letter arrived, Ingalls had already flown her way into the debate over U.S. intervention in the war. On September 26, 1939, Ingalls buzzed through the restricted airspace over the National Mall in Washington, D.C., to the White House, dropping 5,000 pamphlets in her wake. The message: “Never before in history have American women been so aroused and determined to keep their country out of war.”

Ingalls, who had entered flight school during the Lindbergh boom—that heady moment in the aviation industry between Charles Lindbergh’s solo transatlantic flight in 1927 and the stock market crash of 1929—was again following the famous pilot’s flight path, refashioning herself as a face of the isolationist movement.

The petite pilot, now 47 years old, who had so craved the attention she earned for her aerial derring-do, was no longer a fixture on the country’s front pages. It was unlikely that anyone at Carl’s restaurant on L.A.’s Crenshaw Boulevard, where she dined with Comfort that July 1941 night, would have recognized her without her dark curls constrained by a leather flying helmet and oversized aviator goggles. But among a small and fervent group advocating against intervention in the growing wars in Europe and Asia, Ingalls’s fame was again soaring.

Ingalls’s stage presence, described by an observer as “sarcastic, flippant, fluent and dramatic,” made her an in-demand speaker at events hosted by Lindbergh’s America First Committee and antiwar women’s groups. After their dinner, Ingalls and Comfort would be attending a party hosted by one such group, Mothers of Los Angeles, to raise $450 for Ingalls’s next protest flight to Washington, D.C., the following month. Her earlier trip to scatter petitions over the White House grounds had nearly cost Ingalls her pilot’s license. This time she pledged to hand them directly to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

But that was not the plan Ingalls wanted to share with Comfort. After her trip to Washington, Ingalls confided, she would fly over London and then over Berlin dropping messages of peace. She asked Comfort to accompany her to the warring capitals, but she advised there would be no return trip. “There is much work to be done by Americans over there,” Ingalls said of Germany. “Especially by people who know how to type and have a good command of English.”

As part of her audacious mission to keep the United States out of the war—her “peace mission,” as she called it—the American aviator planned to join the Nazis.

“I FELT IT BEST to play along with her,” Sylvia Comfort wrote the day after her July 1941 dinner with Laura Ingalls. Comfort was not who she had seemed to be when Ingalls met her at an America First Committee meeting the previous month. The devoted isolationist with the open, friendly face who professed sympathy for Adolf Hitler’s leadership and “efficiency” was a spy of sorts.

The 27-year-old part-time secretary worked for the Community Relations Committee of the Jewish Federation Council, an innocuous-sounding civilian organization founded in 1933 to rout out Nazi influence in Los Angeles. Comfort had joined the effort in 1940 when she realized that William P. Williams, the man with whom she had taken a temporary typing job, was not just an isolationist but a vicious anti-Semite who was organizing secret groups in California to take what he called “drastic” action against the country’s Jewish population. Comfort, who was not Jewish, was disgusted by the man, but her continued employment with Williams gave her unique entry into the United States’ most prominent isolationist organizations and access to those within the movement who were motivated by their support for Hitler and his worldview.

Laura Ingalls was among this group, Comfort now reported to her handler at the Community Relations Committee: “She said, in that many words, that she admires Hitler.” Comfort had already seen the distinctive swastika bracelet Ingalls wore—it was an Indian symbol, Ingalls explained—and she had watched Ingalls, standing before an America First Committee meeting, extend her hand into the air in a straight-armed salute. “We ought to adopt an American salute—the outstretched left arm,” Comfort, a stenographer by training, had recorded Ingalls as saying. Ingalls claimed this gesture was “purely American,” taken from the continent’s indigenous people. “And no one can accuse us of being Nazis, for the Nazis use the right arm.”

But over dinner at Carl’s, Ingalls had been more honest about her allegiance. Comfort related all the details of their conversation to her handler. “I am pro-German,” Ingalls had said. By way of explanation, she added that she had been raised by a German nurse and that her mother was German. The latter statement may have been true, but Ingalls would have had to reach back centuries to find a relative who had been born in that country. (Among the relations on that family tree was the popular writer with whom Laura shared a name; Laura Ingalls Wilder, author of the Little House on the Prairie books, was a distant cousin.) Still, Ingalls seemed determined to fly back to her ancestral homeland.

Comfort’s handler made a note on her report. Agent S3—Comfort’s codename—“was instructed to play along with Ingalls as if informant were ready to accompany her on this very adventurous proposition.” Then the Community Relations Committee of the Jewish Federation Council forwarded Comfort’s intelligence to the FBI.

Ingalls seemed to believe Comfort’s feigned enthusiasm for “the PLAN!,” as Ingalls referred to it. Through the summer of 1941, the two frequently spoke about the trip and Ingalls’s efforts to secure funding and safe passage to Europe. Ingalls was preparing to sell her home in Los Angeles and encouraged Comfort to get a passport for the journey, which could take them through Brazil or Argentina and Italy, as commercial travel was restricted from the United States.

Though Comfort did not see in Ingalls the same deep vitriol toward the Jewish community she had witnessed in others in her orbit, Ingalls was certainly aware of the horrors taking place in Germany. It did not deter her. “She told me that I must realize that if I go along with her to Germany, many people will call me a Nazi,” Comfort wrote in another July report. Ingalls offered a simple reassurance to the woman she still believed to be a friend. Comfort reported that Ingalls advised her, “if I am convinced that the Nazis are doing the right thing and have no reservations whatsoever about them, I wouldn’t mind being called a Nazi.”

Comfort made a record of each interaction with Ingalls for her handler and the FBI. By early September, Laura Ingalls’s name was again in front of the FBI director. This time Hoover was much more interested in the flier. “It is believed that an immediate, thorough and discreet investigation [should] be made into the activities of Laura Ingalls,” he wrote.

Through Comfort’s reporting, the FBI watched as Ingalls grew increasingly frustrated by her slow progress toward Berlin. She was still aggravated that the United States government had turned down her offers of assistance, and now the isolationist movement, too, seemed uninterested in supporting her grand vision. “I continue to be convinced that the medium of flying should be introduced into our campaign—in any possible way. It holds the color, action and appeal which nothing else does—but America First hasn’t lifted a finger to help,” she wrote to Comfort in October 1941.

Ingalls’s second flight to Washington had looked like a failure to those in the movement. She had taken off from Los Angeles that past August with little fanfare, in a plane she had painted with the slogan “No A.E.F.,” an objection to reestablishing the American Expeditionary Forces of the Great War. Soon after, Ingalls crash-landed at the Albuquerque Airport, the first accident of her 11 years in the air. She privately claimed sabotage. For several days, she was stuck in New Mexico, unable to rent another plane. Finally, she purchased a commercial airline ticket to complete her trip, but she never made it to the steps of the White House.

Ingalls was even rebuffed by the one group she felt sure would support her grandiose gesture: the Germans. Ingalls often boasted to Comfort about her connections at the German Embassy, and she sent them coded messages signed with the pseudonyms “Ellen” or “Sagittarius.” Comfort knew Ingalls had used her visit to Washington as a cover to meet with a German contact, but the embassy had refused to support her peace flight. Instead, Ingalls was told, “the best thing you can do for our cause is to continue to promote the America First Committee.”

The FBI kept tabs on Ingalls through the fall as she rallied isolationists at America First meetings, quoting from Hitler’s Mein Kampf, and they tailed her through Washington, D.C., when she arrived in the city on December 11, 1941—the day the United States declared war on Germany. Ingalls was on an urgent mission to see Ulrich von Gienanth, the second secretary of the German Embassy and the country’s chief of propaganda in the United States. She wanted the names of those “who can continue our work in this country,” an informant reported.

On December 17, 1941, believing that the woman J. Edgar Hoover now called “among the most active and dangerous pro-Nazis in the Los Angeles district” was finally ready to make her flight to Berlin, the FBI arrested Ingalls on charges that she was working for the Germans.

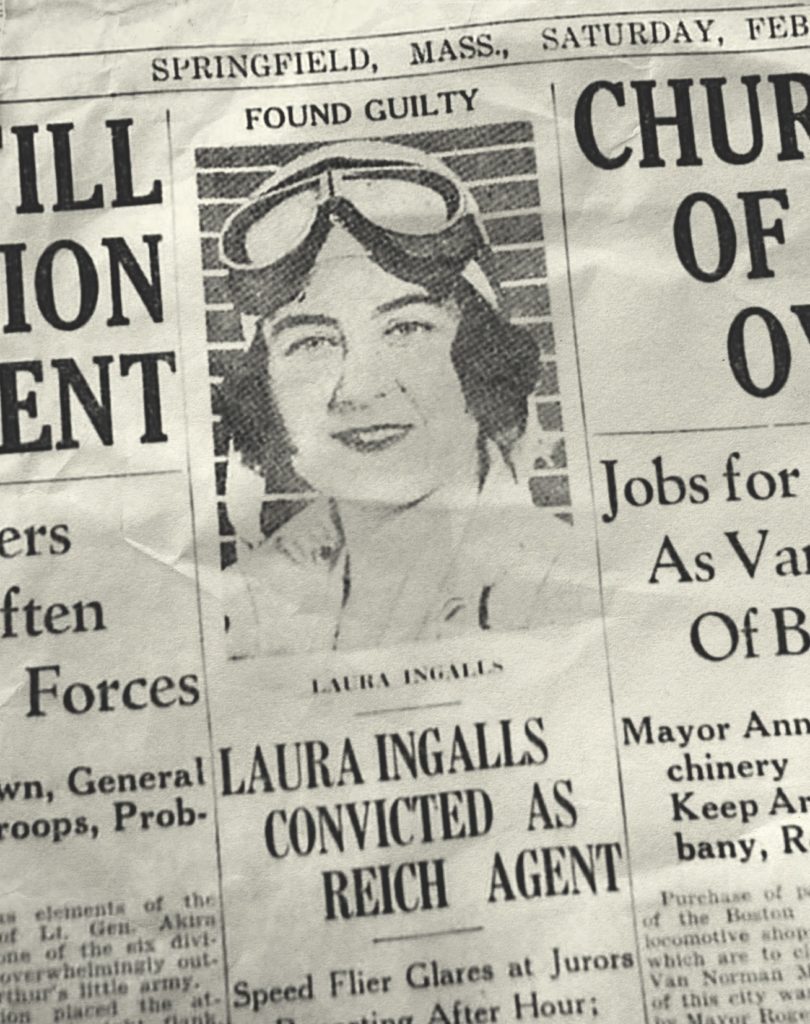

IN A WASHINGTON, D.C., courtroom on February 12, 1942, Laura Ingalls took the stand, the only witness for the defense. Over the previous three days, the prosecution had made the case that Ingalls had violated the 1938 Foreign Agents Registration Act. As the FBI discovered upon her arrest, not only had Ingalls undertaken the work of the German government for nearly a year, she had, for a portion of that time, been secretly paid for her services, all without filing the necessary paperwork with the U.S. government.

Ingalls freely admitted to accepting money from the Germans. She had even negotiated a raise—$300 a month instead of the offered $250; the extra cash came directly out of Ulrich von Gienanth’s pocket, according to a prosecution witness. But, Ingalls argued, she was not what she seemed. Ingalls claimed that she—like Sylvia Comfort, whose role in her arrest Ingalls likely never knew—was a self-appointed spy.

At her arraignment in December, Ingalls declined to enter a plea, instead surprising the court with an impromptu defense: “I don’t take orders from the German government; I was carrying out my own investigation.” She added, “I guess I overstepped.”

At her trial, Ingalls told the jury, “I saw myself as a sort of Mata Hari, an international super spy,” adding, “and I wanted to serve my country.” According to Ingalls, she was a patriot who had espoused pro-Nazi views to ingratiate herself with the enemy. She intended to inform on the employees of the German Embassy and “possibly their superiors in Germany.”

It was, her lawyer said, a “one-woman campaign of counterespionage against the Nazis.” He charged that the U.S. government was on a “witch hunt,” eager to smear the isolationists and embarrass the powerful America First Committee. The defense was difficult to square with the impassioned pro-German sentiments Ingalls had expressed at America First rallies, but her lawyer also willingly acknowledged to the court that Ingalls was “a fanatic” and “a bit of a crack-pot…with a burning desire to make the front pages.” And she had. Throughout the trial, the flier’s face, now framed in a graying bob, again graced newsstands.

It took the jury less than 90 minutes to find Ingalls guilty of spreading Nazi propaganda through her isolationist speeches at the direction of the German government. A few days later, the judge sentenced Ingalls to eight months to two years in prison for her crime. In her statement to the court, Ingalls made one last impassioned isolationist speech on behalf of a movement now distressed by its association with her.

When it had been to her benefit during her trial, Ingalls eagerly disavowed months of pro-Nazi sentiments, expressed both publicly and privately, but she did not abandon the anti-intervention views that had briefly restored her fame. She now thought those views made her a martyr. “One of the great fundamentals implicit in the Constitution is liberty of conscience. I felt that I had a right to follow the dictates of my conscience. I felt that I had as much right to oppose America’s participation in the war as those who were trying to push America into war,” she said. In the isolationists’ battle, she concluded, “sacrifice is necessary. I am willing to make it.” ✯

This article was published in the December 2021 issue of World War II.