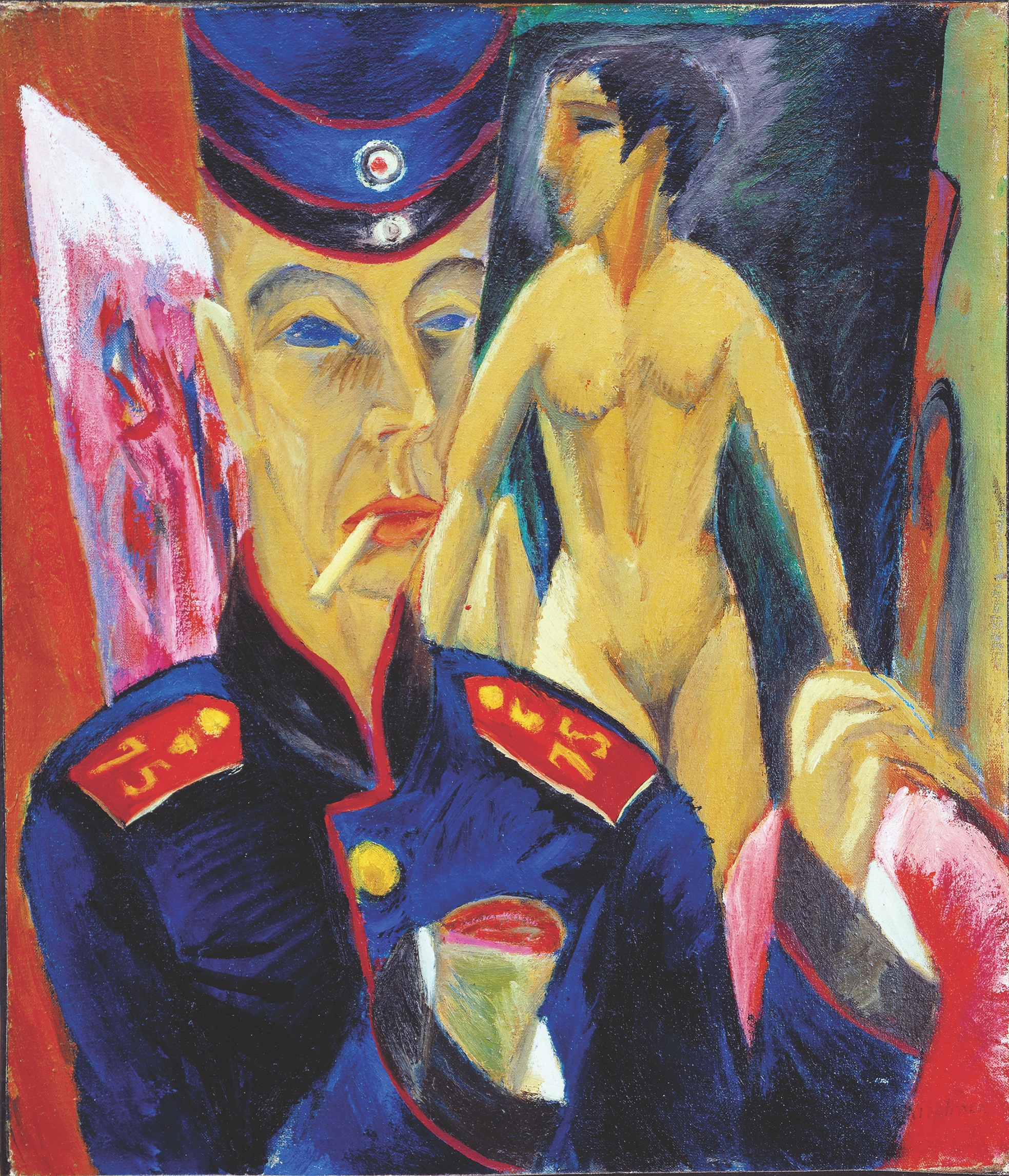

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Self-Portrait as a Soldier remains one of the most famous European paintings produced during World War I. The fame of the work grew from the time Kirchner painted it in 1915. In fact, the self-portrait was his first piece to appear in major museums—first as a loan to the Staatliche Gemäldesammlung in Dresden and subsequently as an acquisition by the Städelsches Kunstinsitut in Frankfurt am Main.

The famed German philosopher Eberhard Grisebach, who visited Kirchner in Berlin in March 1917, offered a respectful assessment of the artist’s works. “Each picture had its own particular colorful character, a great sadness was present in all of them; what I had previously found to be incomprehensible and unfinished now created the same delicate and sensitive impression as his personality,” Grisebach wrote. “Everywhere a search for style, for psychological understanding of his figures. The most moving was a self-portrait in uniform with his right hand cut off.”

Kirchner’s expressionist style, with its bright colors and sharp lines, throws into sharp relief easily recognizable human features. Kirchner represents himself as an artist in uniform. A cigarette dangles from his lips. Alarmingly, his right hand (which Kirchner used to paint) has been cut off, leaving a red but bloodless stump. The left hand bears little resemblance to an actual hand and seems almost to merge with the body of a naked woman just behind the artist. Likewise, his face appears to brush against the arm of the woman. But there is no explicit connection between the two human figures, both of whom gaze with unfocused eyes in different directions. Neither shows any identifiable human emotion.

Few have questioned the meaning of Self-Portrait as a stridently antiwar painting. Certainly, Nazi officials read the image that way. They seized the painting in 1936 and displayed it—presumably as a negative example—in an exhibit of anti-Bolshevik art that same year. More famously, in 1937 they included the work in an exhibition of “degenerate art” in Munich. The Nazis retitled it Soldat mit Dirne (Soldier with Whore).

The standard interpretation of the work as a bitter repudiation of World War I long survived the defeat of Nazi Germany. Generations of art historians, more recently with the aid of gender theory, have affirmed again and again that the painting provides a searing testimony to the artist’s disgust with that conflict. As art historian Donald Gordon wrote in 1987:

The artist cannot paint and soldier cannot fight. His violation is as frustrated as his body is mutilated. The painting’s personal symbolism is one of paralysis and castration, of functional loss both professional and sexual. Its social symbolism, however, is one of defiance and military authority, of an imagined sacrifice of a body part to avoid a battlefield sacrifice of the whole person. If a man must be unmanned to avoid military action, then Kirchner shows by a wished-for amputation a deeply felt pacifism.

Nazi critics in the 1930s and a serious academic art historian writing in the 1980s would of course place radically different value judgments on the work and its message. But if both could arrive at similar interpretations, there would seem little left to explain. Kirchner’s self-portrait represents an emasculated victim, impotently protesting the tragedy of World War I even as that tragedy was still unfolding.

Yet it has always been too easy to assume a connection between the artistic avant-garde in the early 20th century and unconditional pacifism. From well before 1914, the avant-garde concerned itself with finding the proper means of artistic expression—not with rejecting war per se. Indeed, in his Manifesto of Futurism, published in 1909, Italian artist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti embraced a future conflagration. Other figures certainly accepted war when it came. French painters Fernand Léger and Georges Braque responded to the call to arms when their country mobilized in August 1914. Poet and surrealist Guillaume Apollinaire, born in Italy of a Polish mother and Italian father, applied for French citizenship and ultimately joined the artillery. Artists Max Beckman, Otto Dix, and George Grosz all volunteered to serve their German fatherland. In Vienna, Oskar Kokoschka sold paintings expressly to pay for his equipment to serve in the cavalry of Austria-Hungary.

Kirchner held a unique place as a rising star in the European avant-garde before the war. A member of Die Brücke (The Bridge), a group of German expressionist artists founded in Dresden in 1905, Kirchner marshaled his talents against realist artistic convention. But members of the group also acknowledged deep connections to older, particularly artisanal traditions—such as the work of Albrecht Dürer, Mathias Grünewald, and Lucas Cranach the Elder. Not by coincidence, all had been important figures in a distinctly German school of Renaissance art.

A fine book by Peter Springer, Hand and Head: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s “Self-Portrait as a Soldier” (University of California Press, 2002), details the origins and exhibition history of the painting. In 1914, when Germany mobilized for war, the 34-year-old Kirchner placed his name on a recruitment list for the artillery. In April 1915, he wrote to his friend, art critic Gustav Schiefler: “I went to the muster for the field artillery, a beautiful and for me interesting division. I am now waiting for the call-up; when you’re in the military you always have to wait.”

By then, the Great War had already transformed how Europeans waged war. The carnage on the Western Front had reached unprecedented levels. No one could tell how, when, or even whether the conflict would end. In May 1915 Kirchner entered Manstein Field Artillery Regiment No. 75 (the number on his uniform in the self-portrait). He served behind the lines and became strongly attached to the horse he tended.

Before the war Kirchner’s mental state was less than stable, a condition exacerbated by poor physical health. He drank, smoked heavily, and used morphine and barbiturates. Once in the army, he all but stopped eating.

An understanding commanding officer excused Kirchner from regular drills on the thin pretext that the unit needed his photography skills. But Kirchner’s health continued to deteriorate, and he was given a leave to recuperate. Perhaps not by coincidence, the field surgeon authorizing the leave soon found himself in possession of a Kirchner painting. By December 1915, Kirchner’s superiors rendered his medical leave permanent and discharged him from the army. Thus, Kirchner’s direct military service in World War I was over in a matter of months. Not only had he never been wounded, he had never even served near the front. By 1917, his personal retreat from the war took him to Davos, Switzerland, where he remained most of the rest of his life, which ended with his suicide in 1938.

Art historians, knowing that Kirchner suffered no combat injuries during the war, have interpreted the amputated hand in Self-Portrait as symbolic: The horrible war robbed Kirchner of his creativity, even of his manhood. The artist cannot be a man if he cannot paint or if he can only paint images of walking wounded such as himself. He could only paint art without beauty, the hideous having become the only aesthetic thinkable in the war of the trenches.

But in fact, the very existence of Self-Portrait and other important works from this period suggests that diminished creativity in wartime was the least of Kirchner’s problems. Indeed, he continued to produce artistically significant works, including another war-related painting, Das Soldatenbad (Artillerymen in the Shower), in 1915. To be sure, Kirchner spent much of the war in and out of sanatoriums, in a foredoomed effort to restore his health and to wean him from insalubrious habits, notably his dependence on Veranol, the first commercially sold barbiturate. But it was also during the war that Kirchner began to enjoy commercial success. The Schames Gallery in Frankfurt held an exhibition of his works in October 1916 that provided the artist with unaccustomed financial security. His response was another nervous breakdown and a return to the sanatorium that December. His many wartime and postwar landscapes are unfailingly electric, but arguably, after 1915 he never created a work as powerful as Self-Portrait.

Perhaps more surprisingly, Kirchner’s commitment to the war endured. Like so many other Europeans, he seems to have made a distinction between the world war and his personal war. The world war might be senseless and irreparably damage the lives of those it touched, but Kirchner maintained a highly idiosyncratic form of attachment to it, even from Switzerland. He continued to pursue commissions related to the war effort, including a patriotic statue of the Schmied von Hagen (Blacksmith of Hagen). He wrote to Schiefler in October 1916, some 10 months after he left the army for good: “I want to publish a small book to show the German people that I would gladly contribute something human and artistic, not just with weapons.”

Indeed, it seems plausible to turn the time-honored reading of Self-Portrait as a Soldier on its head. Perhaps the deep anxiety of the painting reflects not so much the artist’s victimization by the war as his sense of his own insufficiency before it. He signed up for duty as a soldier and failed utterly, well before he got anywhere near physical danger. He became a living mockery of his own intentions. The painting presented in lurid colors, to use a slang term of the time, a militärischer krüppel, a “military cripple.” This term of derision meant a weakling not able to live up to the masculine norms of soldiering.

From this point of view, the nude woman in the painting becomes not the objectified emblem of Kirchner’s sexual impotence, as critics have long maintained, but an extension of the author himself. The painting is, after all, a “self” portrait. The conventional reading of the woman as a sex worker seems reasonable, given the frequency with which Kirchner photographed and painted such women. But in Self-Portrait the soldier and the woman almost merge—in the soldier’s left hand and along the woman’s right hand and the soldier’s face. The key to understanding this melding is understanding Kirchner’s mortal fear of returning to active duty, his permanent medical leave notwithstanding. He could not escape what he saw as his own emasculation. He wrote to Schiefler in November 1916: “Right now I’m just like the prostitutes I painted. Whisked away, gone the next time.” The woman remains an objectified site of misogyny, but here a site internalized. She, an alternative embodiment of Kirchner, is very much a part of Self-Portrait.

Kirchner, like millions of Europeans, revised his views of the war shortly after it ended. For Kirchner, the jump was a short one from self-loathing militärischer krüppel to victim of a cruel war beyond his control. After the bitter peace of 1919, Kirchner could blame the totality of individual and collective suffering on the war, which had devoured the lives of millions and, for Germany, resulted in defeat. In 1921, the prospect appeared of a commission to design a monument to students from the University of Jena who had been killed in the war. Kirchner declined, protesting that “the task goes against my inner conviction. I have always been an opponent of war, right from the start, and cannot with an honest and clear conscience work for the glorification of soldiers.” At best, this contention oversimplified his own responses to the war. But in rejecting the chance to compete for this commission, Kirchner could complete his personal journey from acceptance to endurance to repudiation of the Great War.

Kirchner did not so much exhibit bad faith on the matter as change his views on the war more completely and more quickly than he cared to remember. Millions of other Europeans on both sides did the same. By 1921 he could efface the problematic facts of his prior embrace of the war. Kirchner could tell himself that his refusal of the war had been the story all along rather than merely the end of it. His journey consisted of his journey’s end, pure and simple.

Thus, if read as a monument that represents the Great War as victimization and tragedy culminating in complete renunciation of the Great War as a worthy cause, Kirchner’s Self-Portrait as a Soldier is not in fact an avant-garde work at all. Kirchner simply expressed in strong lines, bright colors, and facial expressions, harrowing in their blankness, a point of view that by the 1920s had become utterly mainstream in European culture. The task of the historian lies in disentangling the historically specific meanings of the object at different points in time. What a painting came to mean is not what it always meant.

The Nazis would later reinforce Kirchner’s own interpretation of his work by including it in their exhibit on “degenerate art.” By World War II, Self-Portrait had fallen to into obscurity. Under unknown and perhaps dubious circumstances, Kurt Feldhausser, a private collector (and possible Nazi Party member), acquired it in 1943. After Feldhausser’s death in an air raid in 1945, his mother sold the painting to Erhard Weyhe Gallery in New York. Oberlin College purchased the work from the gallery in 1950. Because the Nazis seized the work from a public museum rather than a private individual, it is not considered “looted” art in the manner that has led to so much controversy with other objects. In the fraught world of provenance, Oberlin’s claim to the work appears to rest on solid legal ground. Kirchner’s Das Soldatenbad, in contrast, was returned to the heirs of the prewar owner by the Guggenheim Museum of New York in 2018.

Like many museums, Oberlin’s Allen Memorial Art Museum does not reveal what it paid for objects in its collection. But local folklore has the price at a pittance compared to its present immense value. At the very least, the curators of the Allen at the time made a shrewd guess as to its future value. In artistic and art market circles, by the 1950s, German Expressionism became respectable. It provided a contrast to the patriotic “realism” fetishized by Nazi Germany, as well as the similar aesthetics of Socialist Realism in the Soviet Union. Ironically, the Cold War made avant-garde Expressionism mainstream. Almost as soon as Self-Portrait arrived, Oberlin began to loan it out for exhibitions. It remains one of the most famous objects in the Allen’s entire collection. MHQ

Leonard V. Smith is Frederick B. Artz Professor of History at Oberlin College. His most recent book is Sovereignty at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 (Oxford University Press, 2018).

[hr]

This article appears in the Winter 2020 issue (Vol. 33, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Artist | Fallen Star

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!