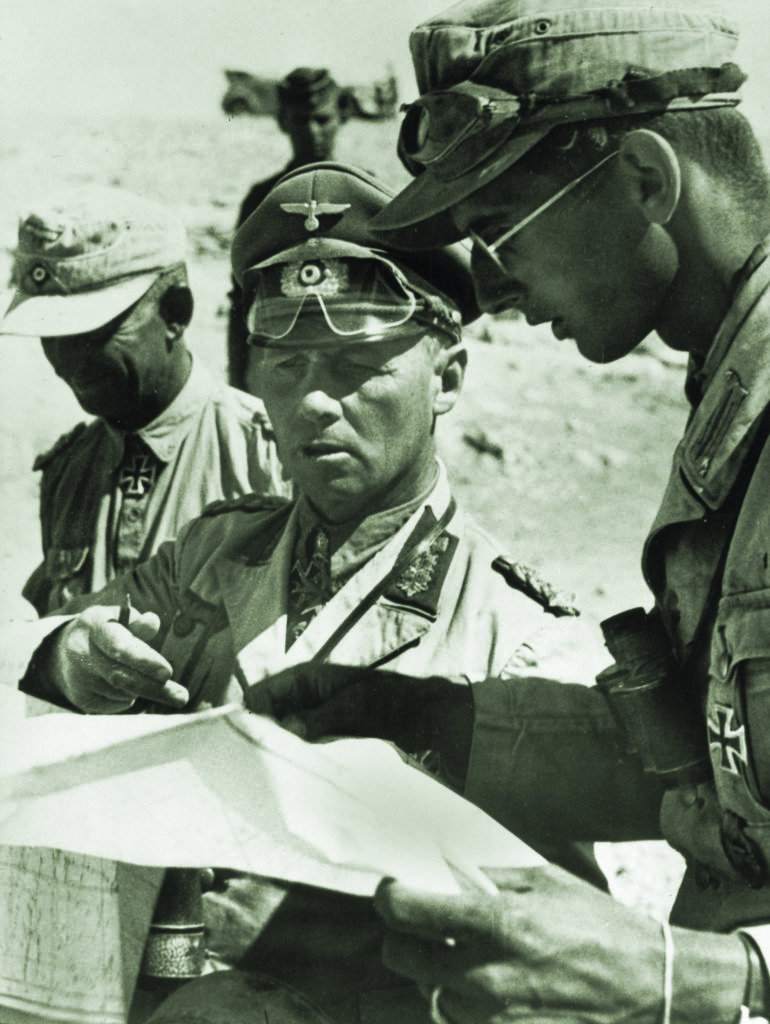

AS OFFENSIVE OPERATIONS GO, the plan was simple with a potentially enormous payoff. A select force of British commandos would sail westward aboard two submarines from Alexandria, Egypt, to the northern coast of Libya, disembark at night in rubber rafts, and paddle to a deserted stretch of beach well behind German lines. From there it was just 13 miles to their target: the headquarters of the German army’s Panzergruppe Afrika. A small squad would work its way around German sentries, stealthily enter the building, and capture or kill the villa’s primary resident: the panzergruppe’s commander, Lieutenant General Erwin Rommel—the “Desert Fox” himself. Mission accomplished, the commandos would return to the submarines, preferably with Rommel in tow, and sail triumphantly back to Egypt. The force’s leader, Lieutenant Colonel Geoffrey Keyes, just 24, reckoned it would be a job “that would be heard all over the world.”

It would, though not in the way Keyes imagined.

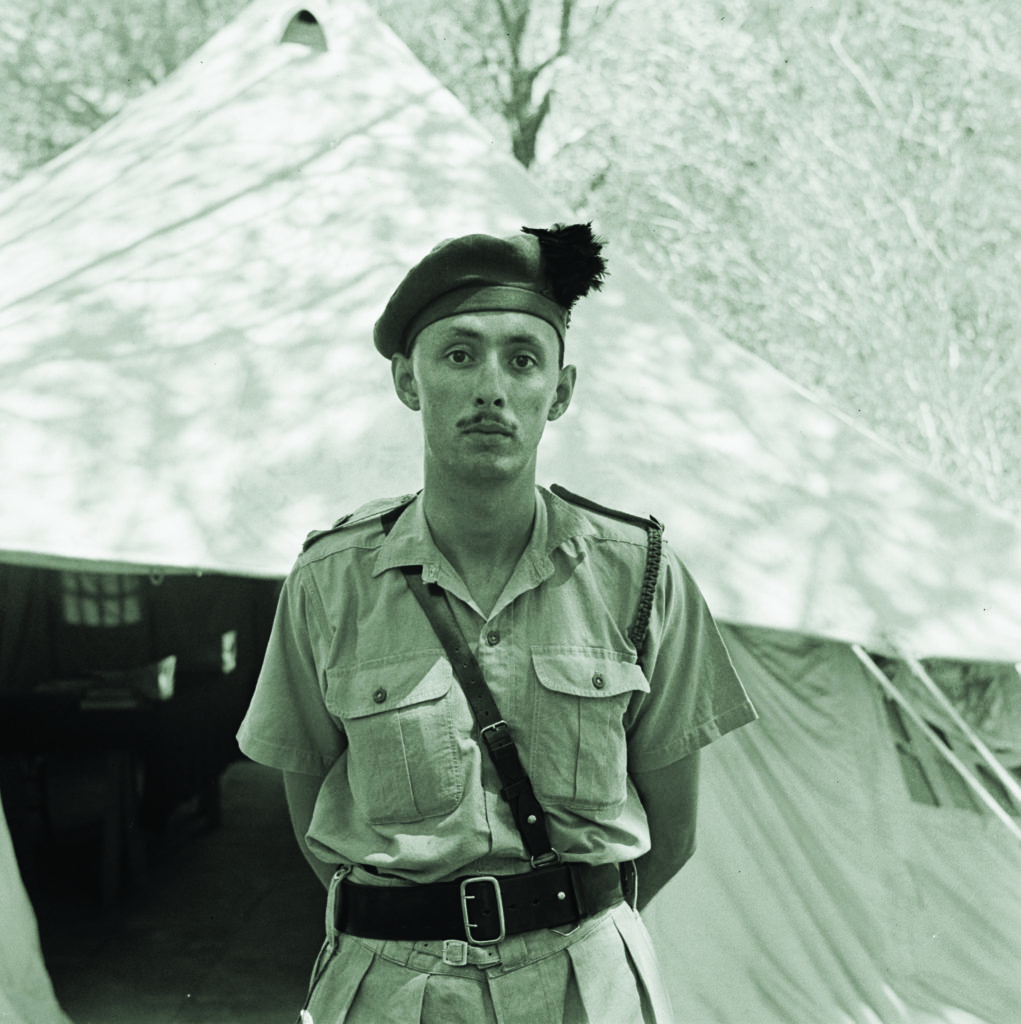

GEOFFREY CHARLES TASKER KEYES was a young man in a hurry. His grandfather had been a knighted general in the British Indian Army. His father was a famed World War I naval hero, recipient of a knighthood and a baronetcy. The lad had a lot to live up to and wasted no time trying to make his own mark. After graduating from Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, he joined a cavalry regiment in 1937, saw action in Norway, and in 1940 volunteered for a wholly new warfighting unit—the Commandos.

Its creation was a direct result of the debacle that spring on the beaches at Dunkirk, France, where a relentless German advance had trapped the bulk of the British Army and other Allied troops, necessitating the famed impromptu evacuation. In a speech to the House of Commons on June 4, Prime Minister Winston Churchill argued for the immediate establishment of forces that could conduct small-scale raids in enemy territory. A news correspondent during the 1899-1902 Second Boer War, Churchill was delighted when his staff suggested calling them “Commandos,” based upon the military successes of the irregular Boer militia Kommandos that fought and harassed the British Army throughout that conflict.

The following month, Churchill placed Sir Roger Keyes, an admiral who had led a successful raid against German submarine facilities in Belgium during the First World War, in charge of all Commando activities. His son Geoffrey, then a captain, wrote his father on July 24 to say that he had signed up for a position in the new forces. “I’m glad you applied—because I was going to apply for you,” the admiral replied. That same day young Keyes wrote his girlfriend: “I am on top of the world, as I have just got the most superb job, [with] infinite possibilities for the future.”

On February 1, 1941, a special-mission unit of 1,500 freshly trained Commandos—called “Layforce” in honor of commanding officer Colonel Robert Laycock and divided into three battalions—departed Glasgow bound for the Middle East. One battalion saw action in Libya, another in Crete. Their losses were heavy: the Germans captured nearly 700 men. Geoffrey Keyes’s unit, meanwhile—No. 11 (Scottish) Commando—bided their time bolstering the British garrison in Cyprus before being sent in June to Southern Lebanon to participate in a campaign against Vichy French troops. On June 9, during their first fight, at the Battle of Litani River, Geoffrey Keyes—then No. 11’s second in command—saved the day when his troops captured an enemy redoubt. But No. 11 took fearsome casualties, losing a quarter of its strength, with its commanding officer among the more than 40 killed. Command immediately devolved upon young Keyes: “There is rather a lot of responsibility attached to commanding a battalion at my age,” he wrote.

THE BATTALION’S REMNANTS returned to Cyprus to regroup. Keyes got the good news that he had been promoted to Acting Lieutenant Colonel—the youngest in the British Army—and awarded the Military Cross for gallantry. But there was bad news, too. Due to the heavy losses, and because the Germans had beefed up resistance to the raids, Middle East Headquarters (MEHQ) ordered the disbandment of Layforce. While fighting raged across the Western Desert as the British Eighth Army tried to push Rommel out of North Africa, No. 11 spent the summer of 1941 lolling about or ignominiously unloading ships in the port. “We will pass peacefully into oblivion when we leave this place,” Keyes wrote in a letter home. “No one wants us here, and we get nothing to do.” He added a plea to his father: “Do what you can for us, Pop.”

Admiral Keyes tried to fix things up. He managed to delay the immediate dispersal of his son’s battalion, which in early August shifted to Egypt to await reassignment. Young Keyes was overjoyed when his colonelcy became permanent the following month. While MEHQ dithered about the future of his unit, Keyes took advantage of the social whirl in Cairo, writing home that, “We continue to have very good parties. Last weekend we bathed all day and danced all night.”

It was while hanging around headquarters that the young officer picked up a juicy bit of intel from a staff officer: General Rommel had been sighted at Beda Littoria, a small town high in the fertile Green Mountains of northeastern Libya, and had set up a headquarters there alongside the Italian Army’s XXI Corps. That got Keyes thinking. Checking a map, he saw that Beda, though well behind the front lines on the Western Desert, was just a few miles from the coast of the Mediterranean Sea—within easy marching distance for a submarine-delivered raiding party tasked with going after the Desert Fox.

On October 4, 1941, he shared his brazen idea with Captain R. T. S. “Tommy” Macpherson, No. 11’s executive officer. Macpherson wrote in his diary—in red ink—“A red letter day! Geoffrey found a great idea. He said, ‘If we get this job, Tommy, it’s one people will remember us by.’”

To make the idea more palatable to MEHQ, Keyes outlined three other objectives, designed to knock out Italian communications facilities. The proposal circulated at high echelons for a couple of weeks. The thinking was that the raid would tie in nicely with Operation Crusader, a British offensive to relieve the beleaguered garrison at Tobruk—also in Libya—set to kick off on November 18. If Keyes’s plan worked, the loss of Rommel, a brilliant tactician, would slow the German response to the assault.

Commando leader Colonel Robert Laycock reviewed the plan. He was not optimistic, calling the attack on Rommel’s headquarters “desperate in the extreme” and meaning “almost certain death for those who took part.” Headquarters nonetheless approved the raid. Then, in a bit of a turnaround, Laycock decided to go along on the mission as an observer. He hoped his participation would restore his reputation, damaged after he had disobeyed an order on Crete in June by evacuating himself ahead of his troops.

Lieutenant Colonel Keyes and No. 11 Commando started an intensive training program for the raid, by then dubbed “Operation Flipper.” Practice landings from submarines along the Egyptian coast showed that disembarking should take no more than an hour per sub. Two separate reconnaissance missions of the Beda area began gathering intel. Tommy Macpherson led one, but he and the three men with him were captured by an Italian patrol and imprisoned. The second, conducted by a veteran desert fighter, Captain John Haselden, confirmed that Rommel had been seen at Beda Littoria and had slept at the villa there, the former residence of the local prefect. The Italians called it the “Prefettura.”

By November, Flipper’s troop of 56 men was ready to go. Captain Robin Campbell, 29, the son of a baronet and a former journalist, had been in one of the disbanded units and was pulled in because of his fluency in German; he would be second-in-command to Keyes. Just before departing, Keyes wrote home: “If this thing is a success, whether I get bagged or not, it will help the cause. I am certain I will roll up alright. This is a hell of a chance.”

THE SEAS WERE DEAD CALM the night of November 13, 1941, when two Royal Navy submarines, HMS Torbay and HMS Talisman, trained their periscopes on a stretch of Libyan beach 250 miles behind German lines. When they detected no movement, Torbay’s skipper, Lieutenant Commander Anthony C. C. Miers, urged Colonel Keyes to take advantage of the good weather and land immediately—one day earlier than scheduled. But the Commando leader said no: he wanted to wait until the 14th, when Captain Haselden was to scout the beach and signal “All Clear.” And so the party waited 24 hours at the bottom of the Mediterranean.

But when they surfaced at dusk on the 14th, the state of the sea had changed dramatically for the worse. Through wind-whipped mists, Miers’s crew could barely make out the recognition signals flashed from the beach. While Talisman waited offshore, Torbay moved in to within a few hundred yards. A little after 7 p.m. its 28 Commandos—Keyes and Campbell among them—swarmed onto the deck and began to inflate their two-man rubber rafts. No sooner had the rafts been put into the water than they started to drift away in the strong current, forcing an exhausting retrieval effort and stretching the launch into a six-hour ordeal. By half-past midnight, all Torbay’s Commandos were safely ashore. Now it was Talisman’s turn.

If it took another six hours to get the second team launched, the final rafts wouldn’t reach the beach until after sunrise, leaving the second sub visible and vulnerable to enemy reconnaissance. Still, Laycock, aboard Talisman, decided to go ahead and, at 1:40 a.m. on November 15, landing operations commenced. From the onset, things did not go well. A rogue wave knocked seven rafts and 11 men into the sea. One drowned. Weapons, rations, even shoes, vanished in the current. As dawn approached, they halted the landing; only eight men, Laycock included, had made it ashore. That left 20 still on board, including two Arab guides from the pro-British Senussi tribe, cutting the strength of Keyes’s force by one-third.

Later that morning, Keyes and Laycock reworked the mission plan from the shelter of a ruined house. They reduced the objectives from four to two. Keyes himself would lead the first detachment on the raid to Rommel’s headquarters; he gave Lieutenant Roy Cooke’s seven-man detachment the task of hitting an Italian Army radio facility at Cyrene, eight miles east. Laycock would remain near the beach with seven men to guard their supplies.

Just before sundown on the 15th, Keyes began leading No. 11 Commando, now only 25 strong, on the 13-mile march toward Beda Littoria. For reasons of stealth, they planned to travel mostly at night, with arrival at the Prefettura intended for just after midnight on the 18th. But almost immediately they encountered a steep, rocky escarpment, rising 450 feet above the beach and slowing their progress. At 2 a.m. the next morning, the colonel halted the climb to rest his men. Shortly after daylight, they awakened to shouting from a group of armed Arabs who had surrounded their bivouac. With the help of his interpreter, Keyes calmed the locals and even elicited a promise of assistance from their British-friendly chief.

Rain had begun falling early in the morning and increased throughout the afternoon. As dusk fell on the 16th, the Commandos set off through the morass for the second stage of their march. A few hours later, their local guides led them to a large cave used mainly by goatherds, about four miles from their objective. Once his teams had settled, Colonel Keyes tried to make a reconnaissance of Beda. Unable to get into the town himself for fear of being recognized, he sent a Libyan boy to scout the area. From the youth’s descriptions, Keyes mapped out the buildings they would assault the following night.

The weather worsened on the 17th. “The clouds seemed to open, and a deluge of rain fell,” Captain Campbell recalled. “The country we had to march over turned to mud before our eyes. Spirits were sinking—I know mine were.” Early that evening, the Commandos blackened their faces with burned cork and, at 6 p.m., set off on the final leg. It was even rougher than the night before. “The going became so bad that we were compelled to go in single file to avoid knocking one another over as we slipped and stumbled through the mud,” Campbell remembered. “Every now and again a man would fall, and [we’d] have to halt while he picked himself up.”

After summiting another steep escarpment, Keyes determined his team was a few hundred yards behind the Prefettura. As they moved cautiously forward, an anxious dog in a nearby house began barking. Its owner screamed at the dog, bringing an Arab and an Italian officer out to see what the cause of the commotion was. As they approached, Campbell used his language skills to keep them from getting too close. He told the officers they were a German patrol on a night exercise and ordered: “Go away and keep your dog quiet!” The Italian shrugged, and as he turned to leave, wished the “Germans” Gute Nacht.

Just before midnight, the group reached the rear of Rommel’s three-story, white stucco villa, set in a grove of cedar trees. It was still pouring rain. Keyes set a perimeter guard and took another group of men to the back of the Prefettura. He rattled the door. It was locked. He checked the windows. They were shuttered. That left only the front door.

Seven marble steps rose to a heavy wooden double-door. Rather than storm the entrance, Keyes had Campbell simply knock loudly at the door. The captain’s German proved critical once again—he demanded to be let in. A big bear of a German sergeant armed only with a bayonet opened the door, and the Commandos rushed in before he could react. They were standing on a stone-floored foyer with two doors on the left and a stairway and another door on the right. Keyes aimed his Colt automatic at the man, but before he could pull the trigger, his target grabbed the gun, then Keyes himself. As the pair struggled, Campbell and Sergeant Jack Terry jockeyed to get off a shot. Finally, Campbell fired three times with his service revolver. The foe crumpled to the ground. Campbell remembered Keyes saying that his arm had gone numb.

When another German appeared at the top of the stairs, Terry turned, fired a burst, and the enemy soldier retreated from view. A ground floor door opened and Terry fired again, killing one German and wounding a second. Campbell tossed a grenade into the room, and the sergeant let loose another long burst. That was when, according to Campbell, a bullet fired from within the room hit Keyes. He fell to the floor, mortally wounded. Seconds later, the grenade went off. Complete silence followed. He and Terry pulled Keyes outside. “He must have died as we were carrying him,” Campbell later recalled, “for when I felt his heart it had ceased to beat.”

For decades that was the official version of events. But in his exhaustively-researched 2004 book, Get Rommel, military historian Michael Asher builds a strong case that when Campbell fired at the sentry, one of his rounds hit his colonel—that Keyes was actually a victim of friendly fire. Today this theory is widely accepted.

The scene inside the Prefettura played out in just two or three minutes. By then the whole compound was abuzz with confused German and Italian soldiers, and the Commandos were firing at anything that moved, killing two more Germans. In another instance of friendly fire, a British bullet slammed into Campbell’s shin, putting him out of action. He passed command to Terry, only 19, and ordered him to gather the remaining men and clear the area. The raid on Rommel had foundered the moment the German guard opened the door, any thoughts of capturing or killing the Desert Fox evaporating.

Eleven men heeded Terry’s signal to regroup; the rest were captured. The sergeant led his small squad back down the escarpment and toward the beach, where Torbay was awaiting their return. With the enemy on their heels, they made haste, but unrelenting rain and near-zero visibility slowed their progress. About a mile out of Beda Littoria, Terry, in the lead, suddenly disappeared over a cliff. He managed to grab a branch on his way down and, with some effort, his comrades pulled him back up. They spent a miserable night in the bush waiting for dawn. The rain eased by morning, and the Commandos pressed on, reaching Colonel Laycock’s rear guard late in the afternoon of November 18.

The rendezvous with Torbay was set for that night, but continuing rough seas prevented the soldiers from launching their rafts. The next day Italian and pro-Axis Arab troops pressed home an attack on the Commandos, who were mostly holed up in a cave near the beach. After some brief skirmishes with the enemy, the remains of No. 11 (Scottish) Commando were taken prisoner. Only Laycock, Terry, and a corporal—John Brittlebank—escaped. They set out across the desert, eventually reaching British lines in Egypt on Christmas 1941.

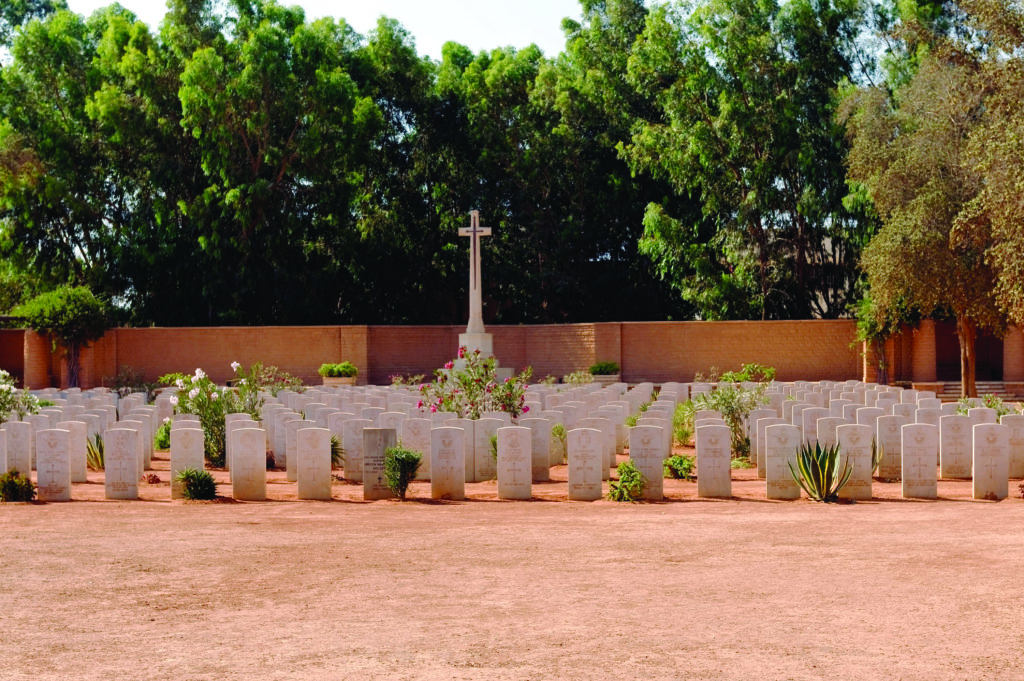

On November 19 the Germans buried their four dead, and Lieutenant Colonel Geoffrey C. T. Keyes, with full military honors in the local church cemetery, the service presided over by a Catholic bishop attached to the Italian Army. That same day, they took Captain Campbell to a German hospital, where his shattered leg had to be amputated. He was freed in 1944 as part of a prisoner exchange. Tommy Macpherson repeatedly tried escaping from a German prison camp before he finally succeeded, in 1944. He made it back to England, returned to the fight, and was awarded a knighthood.

Tactically and strategically, Operation Flipper was an utter failure. It failed to get Rommel or to disrupt Axis communications just prior to Operation Crusader. The key cause can be laid at the feet of British intelligence, which got the situation wrong at every turn: Beda was not Rommel’s panzergruppe headquarters and never had been. At the time of the raid, it was headquarters for Rommel’s quartermaster division. And Rommel was nowhere near Beda when the British came to visit; Captain Haselden’s recce was based upon unreliable information from local spies. Rommel, in fact, had been in Rome, celebrating his 50th birthday. British intelligence had known by November 2—eight days before the submarines carrying the Commandos left Alexandria—that Rommel had departed North Africa for Rome. But the information had not been passed to Keyes.

The Germans initially assumed the raiding party had dropped in by parachute to capture top-secret battle plans. But that was disabused on December 31, 1941, when the British War Department released details of the attack to newspapers around the globe. In California, the Oakland Tribune printed the story on its front page that morning: “British Commando Raid Nearly Captured Gen. Rommel as Libya Offensive Got Started.”

The role of Geoffrey Keyes was prominently mentioned—he was not only the “leader of the British suicide squad,” but the son of World War I hero Sir Roger Keyes. The announcement boosted morale and thrilled Britons, too long accustomed to hearing dispiriting news from the battlefronts. In the New Year, Colonel Laycock put forward Geoffrey Keyes’s name for the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest award for valor. On June 19, 1942, the VC was posthumously awarded to the young Commando. The citation reads: “By his fearless disregard of the great dangers which he ran and of which he was fully aware, and by his magnificent leadership and outstanding gallantry, Lieutenant-Colonel Keyes set an example of supreme self-sacrifice and devotion to duty.”

In 1945 his remains were moved to the Benghazi War Cemetery, the final resting place for 1,240 soldiers from nine Allied countries who fought in Libya during World War II. His grave lies just a few yards from the hallowed Commonwealth “Cross of Sacrifice” that watches over them. In death, Geoffrey Charles Tasker Keyes—a young man in a hurry—tragically fulfilled his destiny to accomplish something “that would be heard all over the world,” finally allowing him a position in his own right alongside his illustrious forebears. ✯

This article was published in the December 2019 issue of World War II.