In late July 1914, American artist Ernest Peixotto and his wife, Mary, returned from a sketching trip in Portugal to the small studio-home in the French village of Samois-sur-Seine that had been their base for 15 years. The town was filled with people enjoying the summer weather: families boating on the river, ladies hosting outdoor tea parties under colored awnings, soldiers on leave sauntering along the streets.

A week later, Germany and France declared war on each other. Overnight, the atmosphere of gaiety disappeared. Five days after the French government posted an order for general mobilization, Peixotto joined the local communal guard. For six weeks, from early August to the First Battle of the Marne on September 12, Peixotto helped patrol the local roads, woods, and fields, watching for spies and deserters.

The Allied victory at the Marne dashed hopes on both sides that the war would be brief. Faced with the prospect of a long and brutal conflict, the Peixottos decided to return to the United States.

Four years later Ernest Peixotto would return to France as one of eight artists attached to the American Expeditionary Forces. As a unit, the uniformed artists were charged with the often conflicting tasks of documenting the war for the historical record while creating stirring images of American soldiers in battle that could be used for propaganda at home.

Peixotto recorded his experiences in sketches and paintings he produced for the War Department and in a powerful memoir of his months as an official army artist, The American Front, published by Charles Scribner’s Sons in 1919.

Peixotto was born into a prominent San Francisco merchant family in 1869. He studied painting first at San Francisco’s School of Fine Arts and then at the Académie Julian in Paris, one of the most respected art schools in the world at the time. By the time the war began, he was well established as a painter and illustrator. He showed paintings at important exhibitions in Paris, New York, and San Francisco and acquired an international reputation as a muralist. He wrote and illustrated his own travel books, and he illustrated books written by others, including Theodore Roosevelt’s Oliver Cromwell: The Story of His Life and Work (1904).

When the United States officially entered World War I in April 1917, Peixotto and other artists were eager to lend their pencils and paintbrushes to the effort.

As the American secretary of the aid organization Appui aux Artistes, Peixotto was in close contact with artists in France and aware of what they were doing to help the French war effort. In July 1917 he wrote an article for the American Magazine of Art in which he urged the government to enlist artists to help in the war effort. Titled “The Use of Art in Warfare,” the article suggested that the U.S. government could not only call on artists to create camouflage and design recruiting and propaganda posters but could also follow the French example and create an official department of war artists.

That same month, the newly created Committee on Public Information, a semiofficial propaganda agency of the U.S. government, recommended that artists be commissioned for special service with the AEF—an idea that may have been inspired by Peixotto’s article. For several months, both the committee and the U.S. Army Signal Corps explored the idea, but in the end the Corps of Engineers took over the project, with the support of General John J. Pershing, the commander of the AEF on the Western Front.

A committee headed by illustrator Charles Dana Gibson, who had earned fame with his stylized “Gibson Girl” drawings, selected eight artists, all of whom were commissioned as captains in the U.S. Army. (Accredited war correspondents were given the same rank.) All eight had strong backgrounds as commercial illustrators, with work published in such popular magazines as Harper’s, McClure’s, and Scribner’s.

Peixotto, who was considerably older than the other artists under consideration, was the third artist to be offered a commission. He accepted without hesitation.

On March 14, 1918, just 10 days after receiving his commission, Peixotto sailed for France along with fellow artist Wallace Morgan on the USS Pocahontas, a German ocean liner formerly known as the SS Prinzess Irene that the United States had commandeered when it entered the war. When they arrived in France two weeks later, Peixotto and Wallace reported to the AEF’s general headquarters at Chaumont after being misdirected to the Corps of Engineers’ headquarters at Tours. Though Pershing had approved the appointment of “The Eight,” as the group of artists soon came to be called, no one was quite sure what to do with them. Eventually Pershing’s staff decided that though the artists held commissions in the Engineer Reserves, they should be attached to the Press and Censorship Division of the AEF’s Military Intelligence Branch and stationed with the accredited war correspondents. Despite the dual nature of the artists’ mission, Pershing’s staff clearly saw their job as another type of reporting.

Lieutenant Colonel Walter C. Sweeny, who was in charge of the Press and Censorship Division, immediately asked the artists to give him a report outlining the supplies and conditions they would need to work effectively. At the top of their list was as much freedom of movement as possible. Sweeny agreed. When the artists asked whether they would need official documents giving them the authority to travel and make sketches, Sweeny assured them that their captains’ bars would take them wherever they needed to go.

Peixotto, however, had his doubts. Deciding to test Sweeny’s assertion, he set up across the street from General Pershing’s quarters in Chaumont, which was close to Sweeny’s office, and began to sketch. Sure enough, a lieutenant in the military police soon appeared and asked Peixotto whether he had orders permitting him to sketch. Peixotto said that he did not. Captain’s bars notwithstanding, the lieutenant apologetically arrested Peixotto. Since the post commandant was out of his office, the lieutenant took Peixotto to Sweeny’s office. Sweeny vouched for Peixotto, who had proved his point, and agreed that the artists would need written orders permitting them to move as they wished through the American occupied zone.

With identity papers and permanent passes from both the American and French commands, Peixotto and the other artists headed to the forward trenches. For several weeks Peixotto traveled from sector to sector, visiting various divisions to get a taste of how soldiers lived—and fought—in the trenches. At each location, Peixotto trudged through the trenches in borrowed rubber boots and his own “tin hat,” ankle-deep in red clay mud so slippery that he struggled to stay upright, noting the construction of different dugouts and the personalities of different divisions.

American soldiers were not yet involved in offensive warfare, but even in the quietest sectors, Peixotto experienced what he described as “bits of real warfare.” He heard the “pap-pap-pap” of German machine guns while visiting the trenches of the 32nd Division in Alsace and was shelled by German artillery as he walked between observation posts along the Canal du Rhône, on the edge of no man’s land. The reality of war came closer yet when Peixotto was sketching in an advanced position. He failed to notice puffs of brown smoke, one after another, coming nearer to him—evidence of shrapnel fire. Finally the lieutenant in charge of the battery poked his head out of his dugout and yelled: “Come in out of that, Captain. That’s a very unhealthy spot just now; they’re trying to get our range.”

On May 30 the Germans broke through the French line. A few days later they had fought as far as Château-Thierry. The AEF’s period of preparation—and that of its official artists—was over.

Peixotto arrived in Paris on June 1—just in time to experience a major air raid. Through four separate attacks, he remained trapped on a rail siding with just the roof of a railroad car for protection. (In his memoir, Peixotto admitted that he was terrified—the only time he used the word in 230 pages, even though he was frequently under fire.) When he returned to headquarters a few days later, the first days of the Battle of Belleau Wood were over. He hurried to the Aisne-Marne Sector to be sure that he didn’t miss the end of the battle as well.

By his own account, Peixotto witnessed part of every important AEF offensive thereafter. He watched American troops march into Château-Thierry in July and followed the Allied advance toward Fismes, in early August. He arrived at the front on the eve of the Battle of Saint-Mihiel in mid-September, and he watched Pershing, French general Philippe Pétain, U.S. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, and French premier Georges Clemenceau enter the liberated city to welcoming cheers at the battle’s end. He was with American forces at the beginning of the Meuse–Argonne Offensive in late September and returned to the Argonne Forest twice in October.

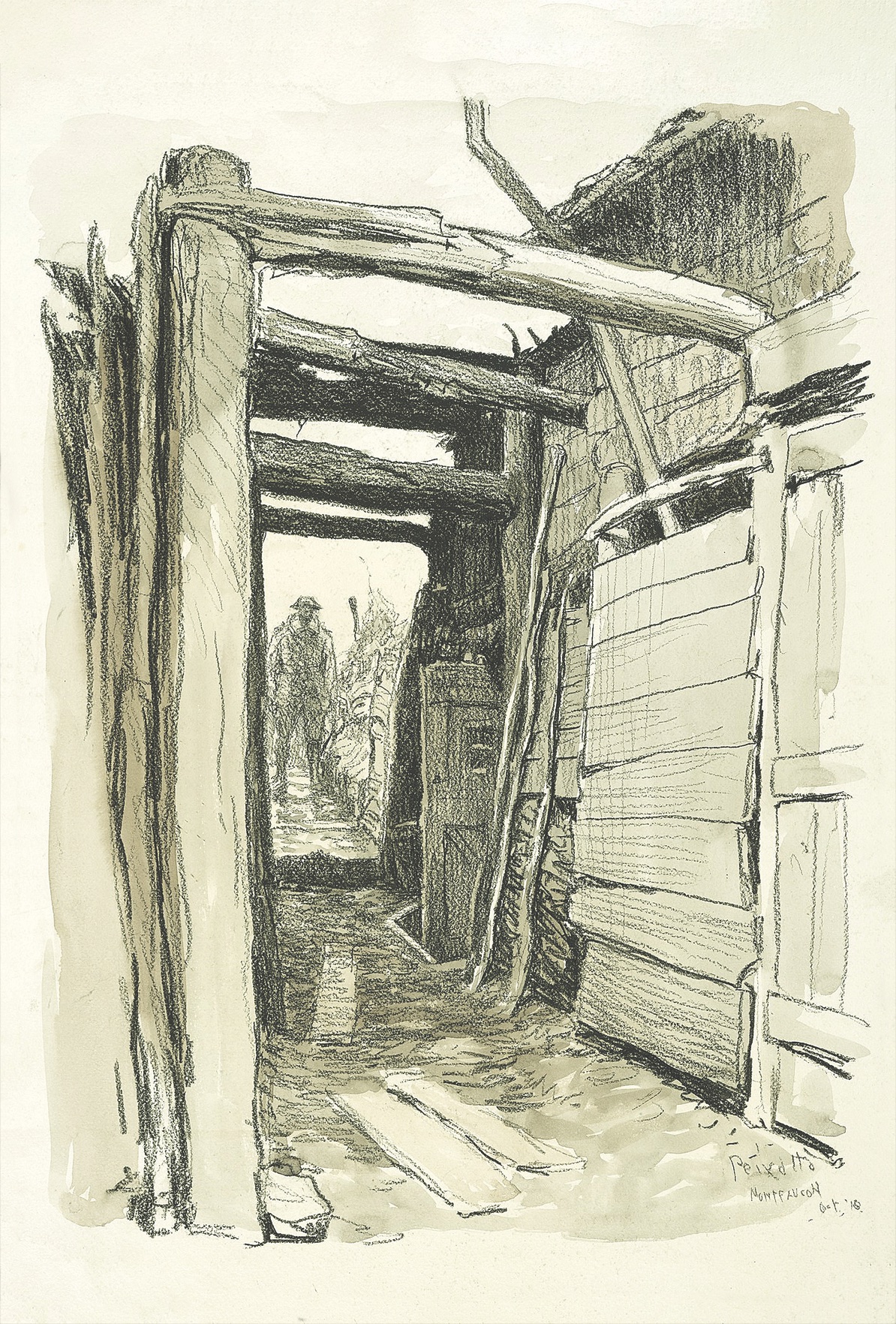

Peixotto’s last trip to the forest cost him the chance to witness the final weeks of World War I. After following the AEF for several days, he made a studio and base camp for himself in a deserted room in Rarécourt. The weather was foul—“rain and slush; mud and dirt,” he later wrote. Inside was not much better, with a fireless fireplace and a leaking roof. Drawing was a challenge because his paper was damp and his hands were numb from the cold. Nonetheless, he made sketching trips to Montfaucon, where he drew the remains of the German fortifications there, and to observation posts overlooking the grim wastes of Hill 304 and Le Mort Homme.

Peixotto followed the progress of the AEF until the Germans stopped their advance and a serious bout of flu—this in the middle of the 1918 influenza pandemic—stopped his own advance at much the same time. His commanding officer ordered him to take time off to recover, which he chose to spend at his studio-home in Samois-sur-Seine.

After his recovery, Peixotto went to Paris for the signing of the armistice. He then returned to his unit at Neufchâteau and continued to make sketching expeditions, recording the impact of the war on the French countryside. (On one trip he arrived at Sedan some hours before Pershing made his official entrance into the liberated city.)

Peixotto’s memoir is a vivid account of his time with the AEF. He describes the discomfort of life in the trenches, the sensory realities of the battlefield, and his own reactions to what he saw.

His art is more distant from the experience of battle, though he often worked on the edge of an active battlefield. Many of his pieces depict ruined towns and the blighted French countryside. In piece after piece, the remaining walls of bombed-out churches are surrounded by mounds of rubble and debris. In others, roads stretch into the distance, lined by shell-torn buildings or formerly grand trees reduced to stumps and gaunt skeletons. In one sketch, a large crater dominates the foreground while a row of ruined buildings defines the horizon. The images are tied to the war’s events only by their place-names. Peixotto includes few humans in these scenes; people are so small in scale and impressionistic in treatment that they are reduced to elements in the landscape.

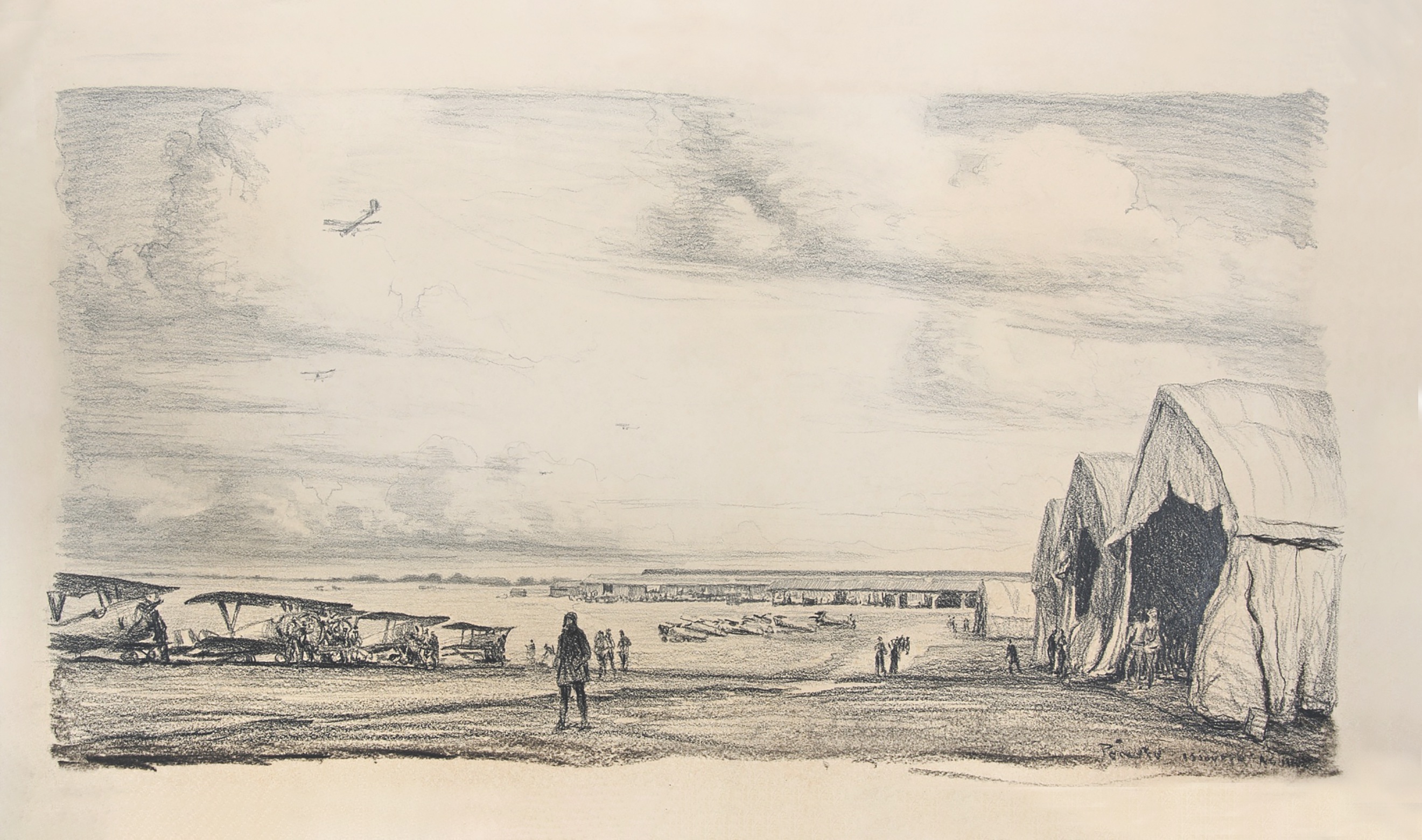

Even those pieces that show soldiers at work often focus on the infrastructure of warfare. Soldiers building a new bridge across the Marne River to replace one destroyed by German bombs. Barracks dug into a hillside. Soldiers playing cards in their billets. Airplane engine shops, locomotive works, and the camouflage depot in Dijon. Planes on the ground at the airfield at Issoudun. Soldiers lining up outside a commissary. A few pieces show troops in movement, but the soldiers are always moving toward battle rather than engaged in battle.

In February 1919, Peixotto was offered one last assignment on behalf of the AEF when it joined forces with the YMCA to provide educational opportunities for the soldiers stationed in France. The most ambitious element of the project was the creation of the AEF’s own university at Beaune, including an art school. Peixotto was offered, and accepted, a position as head of the school’s painting department, though his tenure was short-lived. The university opened its doors on March 17, 1919, but closed three months later with the rapid demobilization of the AEF.

With the closing of the university, Peixotto returned to his interrupted career as an artist. In 1921 the French Legion of Honor awarded him the rank of chevalier (knight) for his work in the war and for promoting friendship between France and the United States. He went on to serve as the president of the National Society of Mural Painters from 1929 to 1935 and was the director of murals for the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Murals, he once observed, “have stirred the feelings of a mass of American people who have never been stirred artistically before.”

Peixotto died at his home in New York City in 1940.

Pamela D. Toler, who writes about history and the arts, is the author of several books, including Women Warriors: An Unexpected History (Beacon Press, 2019).

[hr]

This article appears in the Summer 2021 issue (Vol. 33, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Artists | The Enlistee