John Moncure Daniel, the editor of the South’s leading newspaper during the Civil War, had a penchant for putting his life on the line.

John M. Daniel, the editor of the Richmond Examiner, sat alone in his office as he waited for the poet to arrive. Earlier, they had discussed the possibility of the writer contributing to the newspaper. But they were much alike, these two—-brilliant, brooding, temperamental—and the negotiation had turned sour. It worsened when Daniel made disparaging remarks about the writer’s mounting debt and budding romance. The poet, infuriated, had dashed off a note challenging the editor to a duel.

Daniel knew from the stories circulating in July 1848 that the poet had been frequenting local taverns, imbibing freely, and entertaining his barroom admirers with his latest rhymes. True to form, when Edgar Allan Poe appeared at Daniel’s door, he was drunk.

Daniel packed a lot into his brief, turbulent life. He served variously as a U.S. diplomat, journalist, and Confederate staff officer. He is best known, however, as the rabidly proslavery, secessionist, and anti–Jefferson Davis editor of the wartime Richmond Examiner, the South’s most important newspaper. “No one man in all the Southern Confederacy,” an early biographer of Daniel wrote, “exerted a wider and more powerful influence on popular thought.” Largely because of that power, Daniel’s scathing editorials rankled many people, causing more than a few of them to resort to the peculiarly Southern method of resolving “affairs of honor.” Daniel fought as many as nine duels.

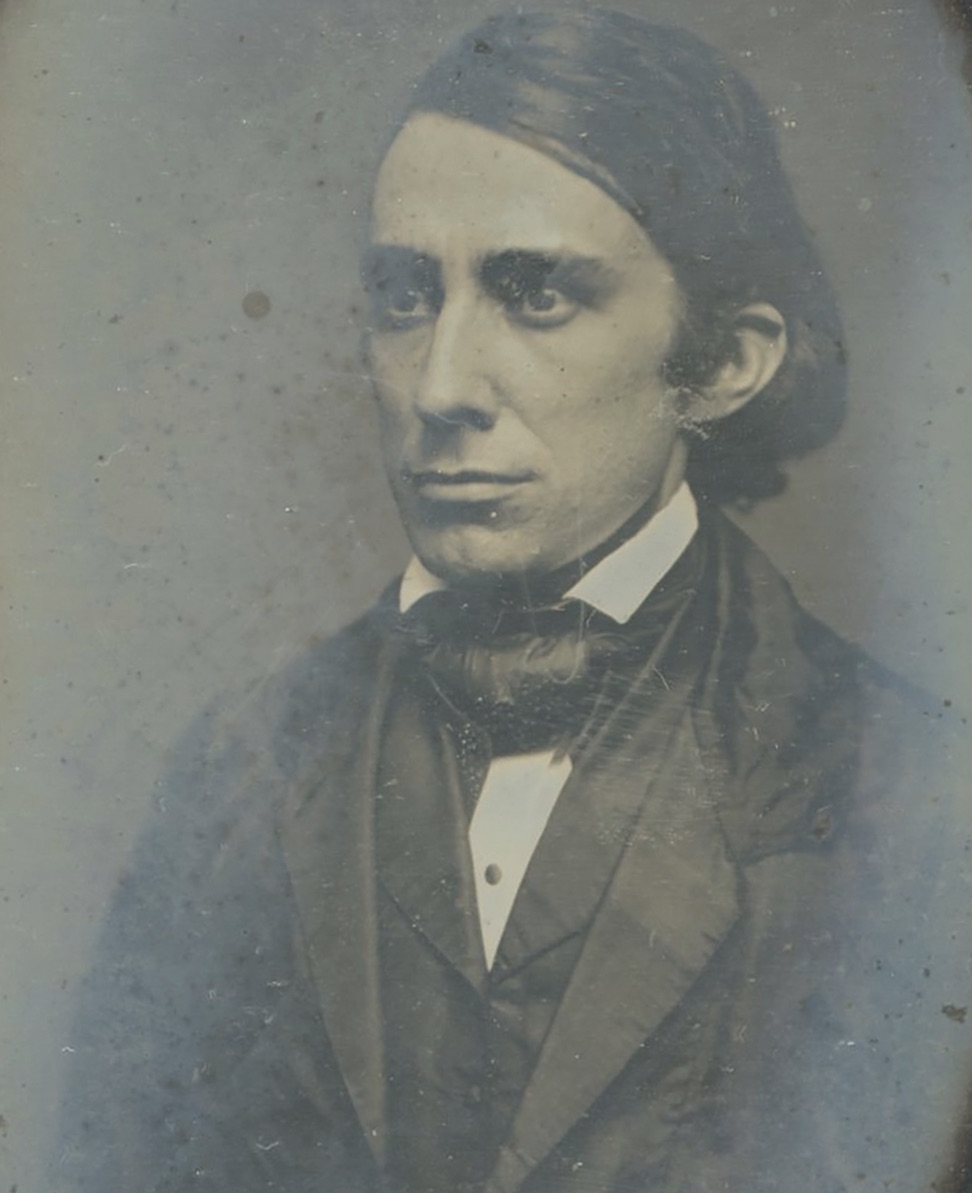

Born in 1825 in Stafford County, Virginia, John Moncure Daniel was at first educated by his father, a physician, after whom he was named. At age 15 he moved to Richmond to attend school and live with his great uncle, Peter V. Daniel, an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. While still young, Daniel, an avid reader, developed a blunt, forceful prose style. Thanks to the judge’s influence, Daniel took up the proslavery point of view and briefly read law in Fredericksburg. Penniless after the death of his father in 1845, Daniel returned to Richmond, where he first worked as the librarian of the Patrick Henry Society, a literary and debating club for the well-heeled.

Around this time Daniel discovered his true calling: journalism. In 1846 he became coeditor of the monthly Southern Planter, an influential agricultural journal, but by early 1848 he was also plying his pen at the newly founded Richmond Examiner. He soon became its chief editor—at age 22—and, in short order, its sole proprietor.

Of medium height, never weighing more than 120 pounds, Daniel had a well-shaped and prominent nose, wore his black hair long, and had piercing dark brown eyes. A coworker described his countenance as “classical” and wrote that Daniel was “capable of expressing the most winning kindliness or the most repellent scorn.”

In July 1848 Daniel’s threatened confrontation with Edgar Allan Poe—the editor’s first brush with dueling—quickly fizzled when the inebriated poet noticed two rather large pistols on a nearby table. Sobering up, Poe asked a few questions and soon determined that the entire affair had gotten out of hand. After Poe died the following year at age 40, Daniel wrote a long essay for the Southern Literary Messenger in which he observed that Poe, an “original individual,” had developed a totally new type of writing.

During the 1850s, Daniel fiercely supported the Democratic Party, prophetically warning readers that Northern opposition to slavery threatened not only the Southern way of life but also the Union itself. In 1850 Virginia’s majority Democrat legislature elected Daniel to the Virginia Council of State, an advisory panel to the governor. In 1852 he was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention. With his slashing editorial style, Daniel made many enemies when he took on Virginia’s predominant Whig Party and threw his considerable influence behind the 1852 Democratic presidential candidate, Franklin Pierce.

That year Daniel fought a well-publicized duel with Edward W. Johnston, the editor of the Richmond Whig. Strangely, the dispute was purportedly over the merits of a sculpture, the Greek Slave, crafted in Italy by neoclassical artist Hiram Powers. Under the surface, however, was the long-simmering feud between the rival Richmond newspapers. It was reported, for example, that the state’s Whigs wanted to knock off the Examiner, which by then had 4,000 readers and soon would be the city’s largest newspaper. Johnston touched off the duel by calling Daniel “a raging slanderer” in print, but it ended bloodlessly on the outskirts of Washington, D.C. Though both men fired, neither was hit. Daniel soon wrote a friend saying that the incident had been exciting; it had removed all his fears related to dueling.

In 1853, to reward Daniel for his support of the Democratic Party, Pierce appointed him chargé d’affaires at the court of Turin in the Kingdom of Sardinia (one of seven kingdoms into which Italy was then divided). Daniel sold his interest in the Examiner but wisely reserved the right to resume editorial control when he returned. Shortly after he arrived in Sardinia, he created quite an uproar when a letter in which he called the kingdom “more trashy than I ever imagined” somehow made its way into print. The letter went on to say that Sardinia’s women were ugly, the diplomats had “heads as empty as their hearts,” and the entire country reeked of garlic. Despite the controversy, Daniel was eventually promoted to minister and retained his post throughout the Pierce and James Buchanan administrations. During his diplomatic tour, Daniel helped boost imports of Southern tobacco, kept American sailors and merchantmen out of trouble, and helped the U.S. Navy maintain its post at La Spezia.

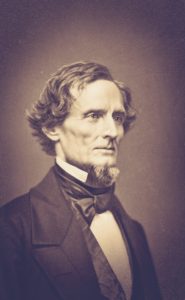

By February 1861 Daniel was back in Richmond at the helm of the Examiner, just in time to add his voice to the Old Dominion’s crisis of secession. By that time, seven Southern states had seceded: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. In early February they had formed the Confederate States of America, adopted a provisional constitution, established a capital at Montgomery, Alabama, and elected Jefferson Davis their president. Thinking that Southern unity was of utmost importance, Daniel became a powerful proponent of Virginia’s secession. On April 19, two days after Virginia cast its lot with the new nation, Daniel wrote jubilantly that “the low-flung and mercenary vulgarity which pervades all the North and inspires the councils of the Yankee president has proved her [Virginia’s] salvation….The Ordinance of Secession places us all together.” Soon he was calling for Davis to be made a dictator, adding that the capital should be moved to Richmond because Davis’s presence there would be “worth an army of fifty thousand men.” (His support for Davis, however, would not last for long.)

As to the reason behind the Confederacy’s creation—the protection and perpetuation of slavery—Daniel was crystal clear: The South’s “peculiar institution” was a moral good. “The presence of an inferior race,” he wrote, “influences and helps to mould the manners and the character of the white man in the South. It inspires every citizen with the feeling of pride and decent self-respect.”

Though Civil War Richmond had several other newspapers, the Examiner now became the most successful of the lot, and in time the whole South was reading it. And nobody was safe from Daniel’s fault finding and acerbic attacks. He called President Abraham Lincoln “an ugly and ferocious old Orang-Outang” and wrote that Davis, whom he’d initially supported, was guilty of nepotism, wasn’t aggressive enough in waging the war, and had appointed incompetent generals and cabinet members. Davis’s wife, Varina, later wrote that while the Examiner was “ably edited,” it went out of its way to make her husband seem odious, which “annoyed and galled him greatly.”

But Daniel’s controversial style also multiplied his readership. Not to read the Examiner in those days, wrote a biographer, “was to miss a part of the history of the times….Into all the recesses of the body politic those shafts of ridicule or denunciation penetrated.” As Daniel told the story, Davis had a body servant pick up a copy of the paper every morning before daylight and, according to the servant, couldn’t “get out of bed or eat his breakfast” until he’d read every word.

In 1861, not content to fight the war in print, Daniel procured a major’s commission and served briefly in western Virginia on the staff of Brigadier General John B. Floyd. The following year Major John Daniel—outfitted with a splendid uniform, a tent he designed himself, and his own enslaved valet and cook—served on the staff of Major General A. P. Hill just east of Richmond. During this period, readers noticed that the Examiner heaped particular praise on Hill and his “Light Division.”

On June 27, during the Battle of Gaines’s Mill, the third of the Seven Days Battles, a .58-caliber minié ball shattered Daniel’s right arm. His two slaves escorted him back to Richmond to recuperate at home. More than two months later a visitor reported that Daniel was still “confined to his bed.” He soon was able to resume working full time, but he never regained the full use of his right arm.

In April 1863—in the wake of the Richmond “Bread Riot,” which featured hundreds of female rioters and the pillaging of numerous shops over shortages of bread—the Davis administration asked newspapers to refrain from mentioning the embarrassing incident. Daniel refused. Instead, the Examiner denounced the women, branding them “a handful of prostitutes, professional thieves, Irish and Yankee hags, gallows-birds from all lands but our own.” Fearing a repeat performance from the protesters, the military unlimbered artillery pieces at major city intersections.

Daniel continued to attack Davis’s handling of the war. He was especially critical of Davis for keeping Northern–born lieutenant general John C. Pemberton in command in Mississippi—the disastrous result of which was Pemberton’s surrender of Vicksburg, and his 20,000-man army, on July 4, 1863. “Had the people dreamed that Mr. Davis would carry all his…doting favorites into the Presidential chair,” Daniel wrote, “they would never have allowed him to fill it.”

At a suburban Richmond soiree, famed diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut was seated beside a stranger, someone she described as “bright and clever beyond my wildest hopes.” During a lively conversation she denounced the Examiner—the newspaper, she said, was “splitting us into a thousand pieces”—and added that the editor deserved to be hanged. Daniel, her dining partner, looking “grimmer than ever,” didn’t let on. Later, Chesnut was shocked to learn that her witty conversationalist had been the infamous editor himself.

Daniel fought his last duel on August 16, 1864. His opponent this time was Edward C. Elmore, the treasurer of the Confederate States of America. The controversy arose after the Examiner reported that an unnamed Treasury officeholder had been gambling at faro with public funds. Worse, it stated, the man had lost immense sums and spent $10,000 to keep the story out of the newspapers. Elmore challenged Daniel to a duel, and the two men met at Dill’s Farm outside the city. Forced to shoot with his left hand, Daniel missed. But Elmore’s aim was true; he hit the editor in the right leg. Recuperating at home, Daniel felt vindicated when Elmore was indicted for betting at faro and fined $500.

By early 1865 both Daniel and the Confederacy were rapidly approaching their last gasps. Daniel was suffering with tuberculosis and pneumonia; the Confederacy was succumbing to hubris, the overwhelming numbers of Union troops, and its overzealous attachment to a god-awful cause. Daniel died on March 30, 1865. The Examiner’s last edition carried the news of his death at age 39. He was buried in Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery.

Union forces captured Richmond on April 3. A fire that day destroyed much of the lower city, including the offices of the Examiner. Confederate Richmond, John Moncure Daniel, and his beloved newspaper were now all gone. MHQ

Rick Britton, a historian and cartographer, lives in Charlottesville, Virginia.

[hr]

This article appears in the Summer 2020 issue (Vol. 32, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: War Stories | The Duelist

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!