Recommended for you

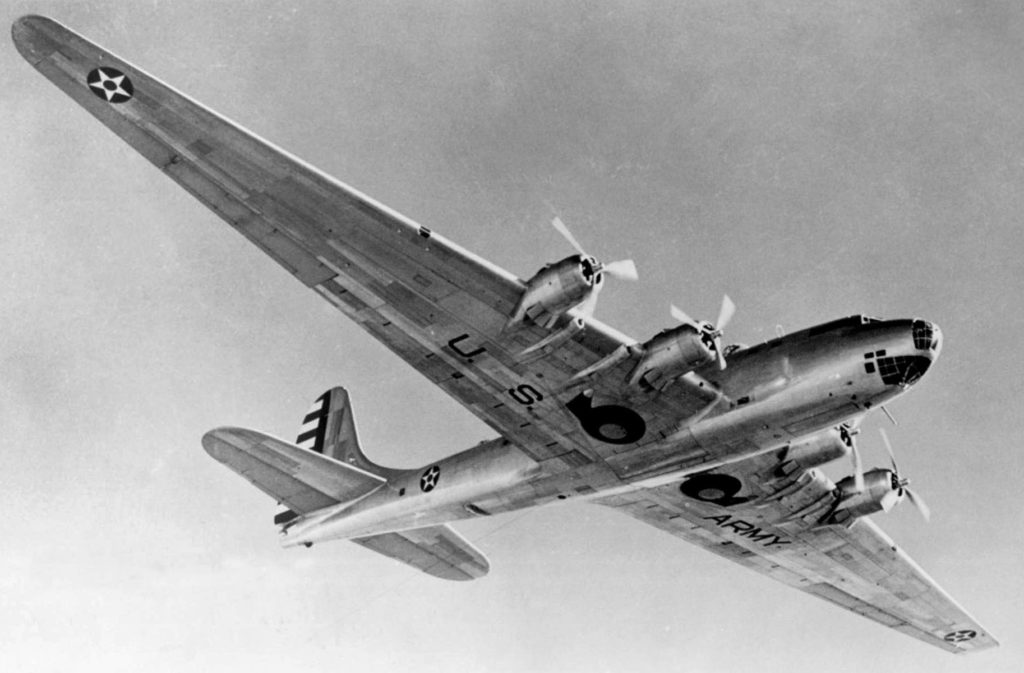

It is somewhat ironic how well-known the XB-19 was in its own time, considering how obscure it has become since. When first flown on June 27, 1941, the Douglas Aircraft Company’s creation was not only the largest bomber in the world, it was also the the largest airplane ever built. The bomber was a top-secret Army Air Corps prototype, but it proved impossible to keep such a gargantuan creation under wraps, and 4,500 people turned out to witness the aircraft’s first flight at Clover Field in Santa Monica, California. It was front-page news in the New York Times. “Biggest Bomber Passes Air Test” read the headline; “Aloft 56 Minutes in Maiden Trip.” Read the article, “Among the spectators were many of the men who worked in the plane’s construction. They cheered wildly as it passed overhead.” President Franklin D. Roosevelt personally telephoned Donald Douglas to congratulate him on his company’s achievement. The XB-19 became featured everywhere in the media, advertisements and animated cartoons. It even received mention in George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart’s comedy, The Man Who Came to Dinner, in which characters dropped the names of every notable person and institution of the day.

How Big Was tHe XB-19?

The XB-19 wasn’t just big, it was humongous. It was 132 feet long, had a wingspan of 212 feet and weighed 162,000 pounds on take-off. To put the scale of the mammoth aircraft into perspective, it was twice the size of the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and 30 percent larger than the later Boeing B-29 Superfortress. In fact, the XB-19 was not bested in size until the advent of Convair’s B-36, which did not fly until 1946. The XB-19 also cost $2½ million to build, a million of which Douglas Aircraft had to absorb.

Operated by a crew of up to 18, the XB-19 was so large that its massive fuselage contained two decks and it had tunnels within the wings so the flight engineer could attend to the engines in flight. The XB-19 could carry up to 36,000 pounds of bombs and had a range of 5,200 miles. Although the defensive armament included two 37mm cannons and five .50-caliber and six .30-caliber machine guns, by the time the bomber flew it was already tacitly acknowledged that the 37mm and .30-caliber guns would be of little practical use.

Why did this super-bomber not appear on the forefront of America’s air arsenal in World War II? For one thing, the aircraft was based upon an Army Air Corps specification that had been issued back in 1935, six years before the United States entered World War II. Those six years were critical, because the state of the art for aviation technology advanced considerably during that period. As an operational bomber, the XB-19 was obsolete before it was even finished. For another thing, engine technology had not kept pace with airframe technology. The engine originally intended to power the XB-19, the Allison V-3420, was delayed, so the design had to be modified to accept lower-powered alternatives. The XB-19 was actually powered by four early examples of the same Wright R-3350 engines subsequently installed in the B-29. The XB-19, however, was so heavy that it was chronically underpowered; to the point where the aircraft had to fly with its engine cooling flaps always open, contributing drag and hampering performance.

Why Was the XB-19 Canceled?

Well aware that the XB-19 would never receive a production contract, by 1938 Donald Douglas requested that the project be cancelled. His company was engaged in much more profitable and higher-priority projects, such as the DC-3 airliner, A-20 Havoc medium bomber and SBD Dauntless dive bomber. Apart from the drain on company facilities, personnel and time, the XB-19 turned into a money pit that ended up costing the company $1 million more than the Air Corps paid for it. Nevertheless, the Air Corps insisted that Douglas complete the aircraft.

Apart from its publicity value, the XB-19 proved its worth as an invaluable “flying laboratory” for the development of new technologies that were applied to subsequent large, long-range bombers like the Boeing B-29 and Convair B-36. In fact, it has been said that the technologically advanced B-29 might never have been developed in time to serve in WWII had it not been for the XB-19.

In 1944 the XB-19 finally received four of the long-awaited Allison V-3420 engines for which it had originally been designed. The engines had also been proposed for an upgrade of the B-29 to be designated the B-39. Although the powerful new engines improved the Douglas bomber’s performance, they never went beyond limited production.

After a long and active, if somewhat obscure, career as a flying testbed, the XB-19 was finally relegated for use as a very large cargo carrier in 1944, although it does not seem to have seen much active service in that role. Laid up at Arizona’s Davis-Monthan Airfield in 1946, the giant bomber was finally scrapped in 1950. Well known in its time, the XB-19 is now almost totally forgotten. The only traces it left behind are two enormous wheels from its landing gear; one at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Ohio and the other in the collection of the Hill Aerospace Museum in Utah.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.