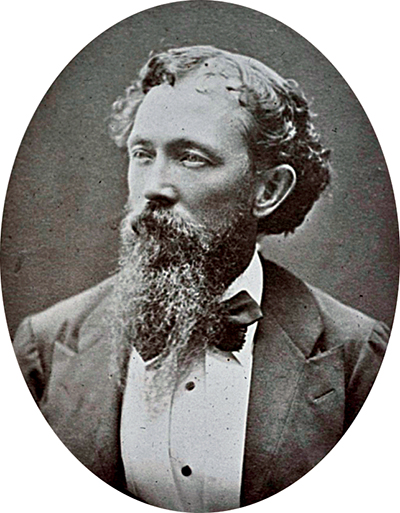

Dr. Isaac Coates and Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer first met at Fort Riley, Kansas, at the outset of Major General Winfield Scott Hancock’s 1867 campaign against the Cheyennes—Custer’s introduction to the Indian wars. “The first thing I noted about [him]…was his laugh, which, soon after I entered the room, burst forth volcanolike until the very windows shook,” Coates wrote of Custer in April 1867. “There was an intellectual vigor, a whole-souled manliness and an indomitable energy expressed in that laugh.” Assigned to the campaign, the doctor would shortly see more of and come to befriend the colonel.

Isaac Taylor Coates was born in Coatesville. Pa., on March 17, 1834, to a Pennsylvania family with deep roots and a good repute if little money. He taught school to pay his way through medical school and earned his M.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in 1858. After making several trans-Atlantic crossings as surgeon aboard the packet ship Great Western for the Black Ball Line of passenger vessels, he served as a physician on various Union Navy ships during the Civil War. On March 22, 1865, Coates married Mary Penn-Gaskel, a descendant of Pennsylvania founder and namesake William Penn. That fall he received a commission from Pennsylvania Governor Andrew G. Curtin, and he served through year’s end as assistant surgeon to the 77th Pennsylvania Infantry, then on Reconstruction duty in Texas. Isaac and Mary had three children (two of whom died in infancy), but he spent most of his life away from home. Descendants surmise he loved his wife but disliked her snobbish family. For much of 1866 he remained on Reconstruction duty in the South as an acting surgeon with the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands.

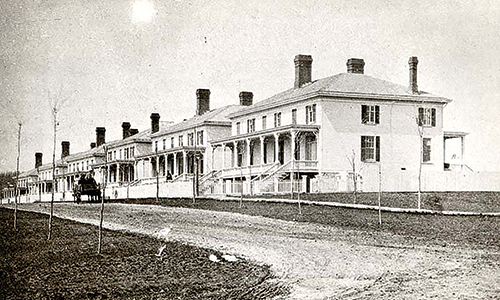

In February 1867, during one of his rare visits home to Chester, Pa., a restless Coates wrote to U.S. Army Surgeon General Joseph Barnes, offering his services as a surgeon for one or two years in “the territories.” Quickly accepted, he was directed to report for duty at Fort Riley, headquarters of the newly created 7th U.S. Cavalry. He arrived on March 22. Eight months earlier an equally restless Custer, who’d ended the war as a brevet major general and taken a long leave of absence, had been appointed lieutenant colonel of the regiment.

Coates and Custer immediately hit it off, the doctor joining General Hancock and the colonel on expedition. Coates was soon the focal point of one of the many seriocomic adventures Custer describes in My Life on the Plains.

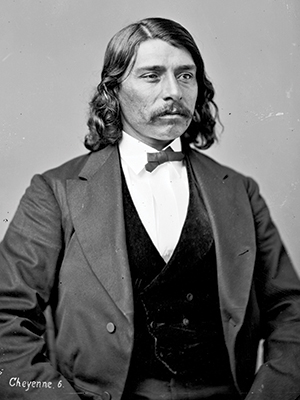

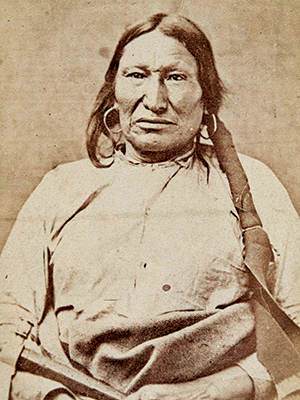

In mid-April, after a conference with truculent Cheyennes under Roman Nose and Bull Bear and Oglala Sioux under Pawnee Killer, the Indians rode back to their village, vowing to return for a full council with the general. But Custer had his doubts, reinforced on the evening of April 14 by intelligence from half-French, half-Cheyenne interpreter Edmund Guerrier, who had accompanied the Indians to their camp and reported they were preparing to leave. Hancock ordered Custer to lead out a strong patrol, surround the village and prevent the Indians from departing. Custer recalled the tense night action:

Directing the entire line of troopers to remain mounted with carbines held at the “advance,” I dismounted, and taking with me Guerrier, the half-breed, Dr. Coates, one of our medical staff, and Lieutenant [Myles] Moylan, the adjutant, proceeded on our hands and knees toward the village. The prevailing opinion was that the Indians were still asleep.…

The doctor, who was a great wag, even in moments of greatest danger, could not restrain his propensities in this direction. When everything between us was being discussed in the most serious manner, he remarked: “General, this recalls to my mind those beautiful lines: Backward, turn backward, O Time, in thy flight / Make me a child again just for one night—this night of all others.”

Coates was relieved and Custer disappointed when the Cheyenne village proved empty. As the curious quartet explored the still-standing lodges, Coates used a horn spoon to ladle a piece of meat from an Indian kettle, examining it with scientific curiosity.

“Ah, here is the opportunity I have long been waiting for!” Coates exclaimed, savoring the aroma of the meat. “I have often desired to test and taste of the Indian mode of cooking. What do you suppose this is?”

Custer merely looked on as the doctor tucked in, finding the morsel delicious. Guerrier, who had lived with his mother’s Cheyenne people for much of his adult life, slipped into the lodge as Coates was eating.

“What can this be?’ Coates again asked.

Guerrier fished a large chunk from the kettle and gulped it down.

“Why, this is dog.”

“I will not attempt to repeat the few but emphatic words uttered by the heartily disgusted member of the medical fraternity as he rushed from the lodge,” Custer wrote.

Moving on to another lodge, Custer and Coates discovered a protruding foot attached to a terrified half-blood girl, no more than 10 years old, wrapped in a buffalo robe. Having Guerrier translate, they asked why she’d been left behind. Her answer quashed their recent mirth.

“After being shamefully abandoned by the entire village,” Custer recalled, “a few of the young men of the tribe returned to the deserted lodge and upon the person of this little girl committed atrocities, the details of which are too sickening for these pages.” Years later Guerrier dismissed her as “a crazy girl.” On examination, however, Coates confirmed that the girl, who he believed to be a full-blood Indian, had been raped. He later questioned whether soldiers had assaulted her, noting in his journal, “Colonel [Edward W.] Wynkoop [agent to the Southern Cheyennes and Arapaho], who declared the girl was an Indian (and an idiot), said there was no instance on record of Indians committing such an outrage on one of their own people.”

The girl wasn’t the only one the fleeing Indians had abandoned in the village. “[Others] found an old, decrepit Indian of the Sioux tribe,” Custer wrote, “who also had been deserted, owing to his infirmities and inability to travel.”

On April 15 Hancock assigned his infantry to secure the empty village and sent Custer with eight companies of cavalry in pursuit of the Indians. The latter raided mail stations and Kansas Pacific rail crews but were never brought to battle. On April 19 Hancock had the Army burn the village of 272 lodges to the ground and destroy all of its possessions in retribution. The column then resumed the chase.

On June 8 a shot was heard in camp. Major Robert Wickliffe Cooper, a 35-year-old Civil War veteran and known alcoholic, was found dead in his tent, his pistol by his side. Coates examined the body and ruled the death a suicide. It appeared the major had acted out of desperation after running out of booze. In a letter written some three decades later, Captain Frederick Benteen—who came to despise Custer—placed the blame on the colonel and the doctor:

On leaving the post of old Fort Hays, Major Wycliffe Cooper, being some days from post and out of whiskey, shot himself—suicide—because the d—-d fool doctor, acting under orders from Custer, wouldn’t give him even a drink of whiskey to “straighten out” on.

For his part, Custer spoke glowingly of Cooper as “a brilliant and most companionable gentleman. He leaves a young wife, shortly to become a mother.” Coates’ own sympathy for Cooper’s widow would get him into trouble. Meanwhile, he faced more immediate perils.

By late June the 7th Cavalry had again caught up to Pawnee Killer, who led the troopers on a wild goose chase while a handful of his warriors dropped back to loot Custer’s supply train. The colonel sent a detachment in pursuit under Captain Lewis McLane Hamilton, a grandson of Alexander Hamilton. Coates rode along in case there was trouble. The captain, in turn, split his command, sending a unit under the colonel’s brother Lieutenant Tom Custer after one group of Indians, while he pursued another. As the troopers separated, the Indians sprang an ambush, placing each unit in peril. In the confusion Coates became separated from both parties. A half-dozen warriors took notice and rode after the doctor. Custer recalled his flight:

How often, if ever, the doctor looked back I know not.…His pursuers, knowing that their success must be gained soon, if at all, pressed their fleet ponies forward until they seemed to skim over the surface of the green plain, and their shouts of exultation falling clearer and louder upon his ear told the doctor that they were surely gaining upon him.…

So close had the Indians succeeded in approaching that they were almost within arrow range and would soon have sent one flying through the doctor’s body, when, to the great joy of the pursued and the corresponding grief of his pursuers, camp suddenly appeared in full view scarcely a mile distant. The ponies of the Indians had been ridden too hard to justify their riders in venturing near enough to provoke pursuit upon fresh animals. Sending a parting volley of bullets after the flying doctor, they turned about and disappeared. The doctor did not slacken his pace on this account, however; he knew that Captain Hamilton’s party was in peril and that assistance should reach him as soon as possible. Without tightening rein or sparing spur he came dashing into camp, and the first we knew of his presence, he had thrown himself from his own nearly breathless horse and was lying on the ground, unable, from sheer exhaustion and excitement, to utter a word.

The detachments managed to repel the Indians, who were loath to mount a charge against troopers armed with revolvers and repeating rifles. But Coates won great respect for his wild ride.

By early July the fruitless pursuit in summer heat across the shadeless Plains on meager rations had taken a toll on Custer’s troopers

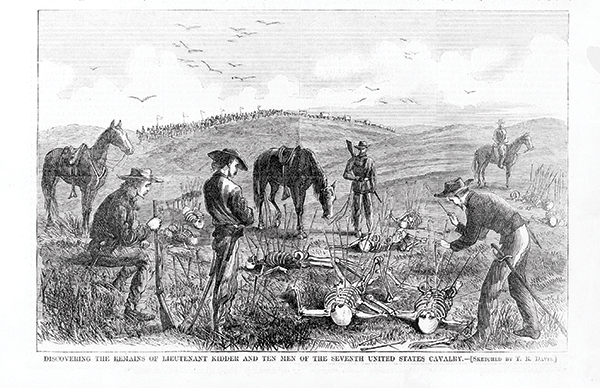

By early July the fruitless pursuit in summer heat across the shadeless Plains on meager rations had taken a toll on Custer’s troopers. More ominously, the cavalry had begun hunting for 2nd Lt. Lyman Kidder, who had vanished days earlier with 10 men and a Lakota scout named Red Bead. Those factors, coupled with word of a nearby gold strike, had convinced a number of men to desert en masse. On the night of July 5 upward of 35 enlisted men did just that.

Two days later came a bold daylight desertion. “Attention was called to 13 soldiers who were then to be seen rapidly leaving camp in the direction from which we had marched,” Custer recalled. “Seven of these were mounted and were moving off at a rapid gallop; the remaining six were dismounted.…This, unfortunately, was an emergency which involved the safety of the entire command and required treatment of the most summary character.”

Custer bluntly described that “summary treatment” to wife Libbie in a July 8 letter he never intended for publication:

I directed Major [Joel] Elliott and Lieutenants Custer, [William] Cooke and [Henry] Jackson, with a few of the guard, to pursue the deserters who were still visible, though more than a mile distant, and to bring the dead bodies of as many as could be taken back to camp.

Custer nemesis Captain Benteen described the incident in a predictably hyperbolic letter written in 1896. “The dismounted deserters were shot down,” he wrote, “while begging for their lives, by General Custer’s executioners: Major Elliott, Lieutenant Custer and the executioner-in-chief, Lieutenant Cooke. One of the deserters was brought in badly wounded, and in extreme agony from riding in wagon (over the Plains without a road), screamed in his anguish. General Custer, in passing by, rode up to the wagon and, pistol in hand, told the soldier ‘that if he didn’t cease making so much noise, he would shoot him to death!’ How’s that for high?”

Within days 7th Cavalry scout Will Comstock found the grisly evidence that Kidder and his men had been encircled, killed and horrifically mutilated. After ensuring they received as decent a burial as possible, Custer led his command into Fort Wallace. The colonel himself then took French leave. Concerned for his wife amid rumors of a cholera epidemic, he led a 75-man detachment on a rapid march to Fort Hays, split off to check in with Colonel Andrew J. Smith, his superior at Fort Harker, then boarded a train to see Libbie at Fort Riley. Almost immediately he received a telegram ordering him back to Fort Harker, where Smith, on Hancock’s orders, placed Custer under arrest.

The court-martial convened at Fort Leavenworth on September 15. Lieutenant Charles Brewster, assigned to Custer’s defense counsel, warned the colonel not to count on his 7th Cavalry officers, as most had refused to testify. The two principal charges were “absence without leave” and “conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline,” the second a catchall that included leaving his command in the field without proper authority and employing troops and government stock on personal business, as well as his July 7 orders to shoot the fleeing deserters.

On September 26 Dr. Coates was sworn in as a witness for the prosecution. “As far as my memory serves me,” he began, “on the 7th of July a number of men deserted while the regiment had halted, and some of those deserters were shot—three of them to my certain knowledge.”

“When you first saw them, did you give them any medical attendance?” the prosecutor asked.

“No, sir,” Coates answered.

“For what reason did you not?”

“When the wagon first came in, I with a number of others started to it,” Coates replied. “As I was going to it, I believe General Custer said to me not to go near those men at that time. I stopped there, just where I stood, of course. I obeyed his order.”

“How long were those men in the wagon before you gave them medical attendance?”

“I suppose two hours.…I administered opiates and made them comfortable, just as I should have done on the field of battle.”…

“Would it not have been better to have dressed their wounds than to have delayed it?”

“It was impossible to dress them on account of not having fresh water,” Coates explained. “We had no water but in the buffalo wallows, and it would have been very hurtful to have dressed the wounds with muddy water.…I waited two days until we came to a stream of clear water—the first we came to.…Sometimes gunshot wounds do not need dressing. Sometimes they do better by allowing the blood to congeal on them. That was the case in these cases. The hemorrhage was arrested by the gluing of their clothing to the wounds. And there was no more hemorrhage after the first hour or so.”

Coates’ testimony had saved Custer from the worst charges of denying medical care to the wounded deserters

Custer then asked to question Coates through his defense counsel.

“When you reached the camp on the night of the 7th and gave the deserters medical attendance, who directed you or instructed you to give them that attendance?” the colonel asked.

“General Custer,” Coates replied. “As far as I recollect now, he said to me, ‘Doctor, my sympathies are not with these men who are wounded, but I want you to give them all necessary attention.’”

Pressed again to answer why Custer had initially directed him not to tend the wounded, Coates spoke to the heavy responsibility the colonel bore at the time.

“I had at that time an idea the objection [to immediate treatment] was made for effect,” he told the court-martial. “There had been a great many desertions, some 30 or 40 the night previous, and the men were crowding around the wagon, and I had an idea the general wished to make an impression on the men, that they would be dealt with the severest and harshest manner.…Soon after I had started to those men—I think just before General Custer moved out with the column, or it might have been immediately after he told me not to go near them—he said, ‘You can attend to them after a while.’”

Coates’ testimony had saved Custer from the worst charges of denying medical care to the wounded deserters. Despite the doctor’s outmoded belief that open wounds don’t require dressing (iodine and other disinfectants were already in field use during the 1870–71 Franco-Prussian War), using water from buffalo wallows, as he testified, would have proved injurious. However, the court found Custer guilty on all other charges and suspended him from rank and command for a year without pay. It was a bitter footnote to his first Indian campaign, which itself had proven less than glorious. Fortunately for him, the brass in Washington felt the same about Hancock’s performance and soon replaced him in Kansas with Lt. Gen. Phil Sheridan. Sheridan appreciated a good fighting officer, and thanks to his intervention, Custer was back with the 7th Cavalry well before his sentence had expired.

In the wake of the court-martial Coates left the 7th Cavalry and the Plains behind and spent a few months as post surgeon at Fort McRae in New Mexico Territory. It was while he was posted there his innate kindness tripped him up.

Sometime in January 1868 a lawyer representing the family of Robert Wickliffe Cooper, the major who’d shot himself in camp the prior June, sought Coates’ help in securing a survivor’s pension for his widow. The Army had thus far denied her petition due to the cause of death. Coates obliged by returning a signed, blank pension form that omitted his medical verdict—a clear violation of U.S. Army regulations. In an accompanying letter, the doctor cautioned the lawyer to practice discretion. Inexplicably, the man forwarded Coates’ signed pension form and the confidential letter to the Army. Oblivious to the attorney’s betrayal of trust, Coates resigned from the service that March, at last report bound for his Pennsylvania home via San Francisco.

The doctor was out of the Army for good—not that he let the dust settle on his boots

On April 21, 1869, after requesting a new field posting, Coates received a terse reply from Surgeon General Barnes. “Your request cannot be complied with,” it read, “as your name had been placed on the list of physicians not to be contracted with again. for the reason of having signed blank Certificate for Pension in the case of the late Major Cooper.”

In 1885, after repeated entreaties by Cooper’s widow, sympathetic U.S. senators finally directed the War Department to change her husband’s record to state he had “died by hand of person or persons unknown while in the line of duty.” But the government’s change of heart came too late for Coates.

The doctor was out of the Army for good—not that he let the dust settle on his boots. He soon embarked on a grand voyage, crossing the country by stage, traveling by ship down the California coast to the Isthmus of Panama, then sailing up the Atlantic Coast to New York and Philadelphia. He returned home just in time to help comfort his first son, Peter, through a fatal case of tuberculosis. Mary gave birth to another son, Harold, as Isaac engaged in a vain effort to get his Army pension. Their last child was stillborn.

Coates then took a job as company surgeon with a railroad in Peru, while there making the first recorded ascent of El Misti, a volcano that towered 19,931 feet in the central Andes. Back in Chester by 1876, he delivered the centennial oration for the community’s Fourth of July committee. A year later wife Mary died at her parents’ home in Philadelphia. Ever the escapist, Coates brought along 7-year-old Harold on a harrowing expedition along Brazilian tributaries of the Amazon River. He and returned with rheumatism and no money. Ironically, in 1881 Harold inherited the considerable properties of one of his mother’s wealthy Irish relatives—the snobbish clan his father had tried so hard to avoid.

By then Isaac had left for Colorado, reportedly for health reasons. For some years he bounced around the Southwest practicing medicine. He was working from an office off the plaza in Socorro, New Mexico Territory, when he died on June 23, 1883, nine months shy of his 50th birthday. The details of his untimely demise remain elusive, though a dispatch in The San Francisco Examiner pointed to suicide. After surviving three decades of harrowing adventures from the high seas to the Great Plains and beyond, the good doctor had taken his own life with an overdose of chloroform. WW

Wild West special contributor John Koster is the author of Custer’s Lost Scout and Custer Survivor: The Final Showdown. For further reading he recommends On the Plains With Custer and Hancock: The Journal of Isaac Coates, Army Surgeon, edited by W.J.D. Kennedy, and My Life on the Plains, by George Armstrong Custer.