The gentleman from Wisconsin engendered at least as much discourse in death as in life

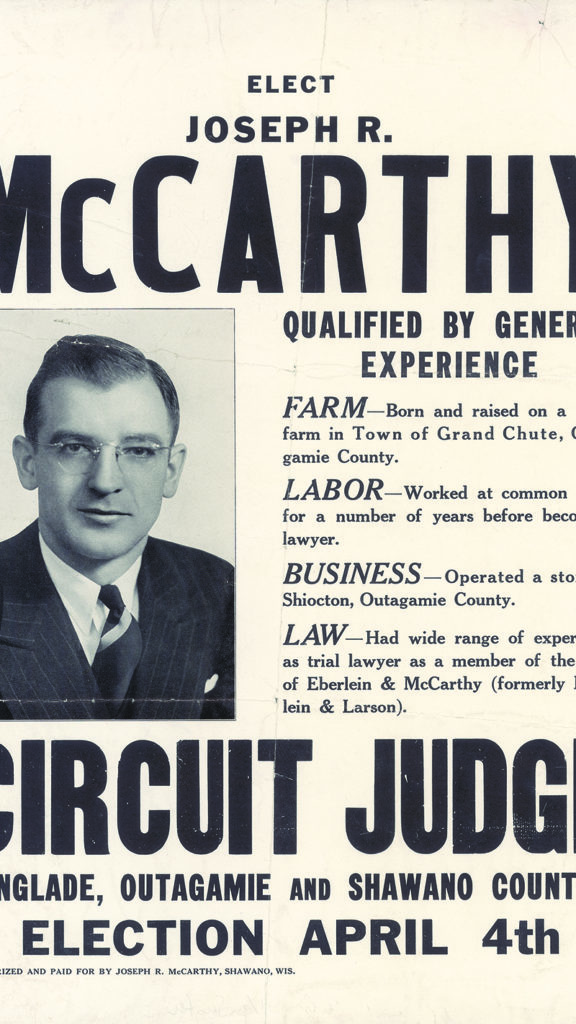

Everyone who ran into Senator Joe McCarthy (R-Wisconsin) that spring of 1957 had a vivid memory of how ill he was—jaundiced skin, unsteady balance, intermittent focus. It was a stunning contrast to the town bully who, a mere seven years before, had captivated the nation with his unsubstantiated charge that there were pinkos lurking behind every pillar at an out-of-touch State Department—and who, on the eve of his 1954 showdown with the U.S. Army, had the backing of a full 50 percent of his countrymen and the swagger that went with it.

“My last view of him was that of a drunk shuffling down a street near the Capitol,” said Irish-American historian George Reedy. “He was closing out the dark side of the victims of the Famine.” Speechwriter Ed Nellor paid the senator a long visit and remembered him as “dazed” and “punch-drunk.” At 1 the next morning McCarthy phoned Nellor at home, rousing his ex-aide from bed to ask when he might be dropping by. He had forgotten! At a meeting of the Wauwatosa School Board, a librarian from McCar-thy’s home-state Milwaukee Journal observed Joe in need of rescue from the board’s cloakroom, where he’d become hopelessly entangled in coats and hardly was able to speak. When editors at the Journal heard about that, they assigned reporter Edwin Bayley full-time to writing the obituary of the pugnacious ex-Marine the world had come to know as Tailgunner Joe.

In his better moments, the senator, a faithful Catholic, seemed to be saying his goodbyes and asking for a kind of redemption. Two-and-a-half years earlier, his Senate colleagues had taken the rare step of condemning him for his incivility, although not for the Red-baiting, accusation by association, fear-mongering, and political double-dealing that had turned the name McCarthy into an ism. “I picked up the telephone and it was Joe. It was the first time we had spoken to each other in exactly seven years,” recalled syndicated columnist and McCarthy nemesis Drew Pearson. “The following conversation took place: ‘Drew, are you sitting down?’ ‘Yes,’ I replied. ‘Well, I wanted to make sure you weren’t standing up or you’d faint. I just wanted to tell you that I’m putting your column today in the Congressional Record. As you know, I don’t always agree with what you say but this column I know tells the truth’…We exchanged a few pleasantries and I thanked him. That was the end of the conversation…I couldn’t help but feel sorry for him. He was a very lonesome guy.”

Another bitter adversary, former Army lawyer John Adams, had a similar experience. Adams’s faceoffs with the second-term senator had been a centerpiece of the famous April 22-June 17, 1954, U.S. Senate hearings into McCarthy’s charges that communists had infiltrated the U.S. Army. “I was sitting in my small law office near the District of Columbia courthouse,” Adams said. “He wanted me to come to see him at his home…I decided to go…He poured about six ounces of Fleischmann’s gin into a glass, added a little tonic and a lump of ice, and lumbered back into the living room. He looked awful. He had lost about 40 pounds, and his hands shook…McCarthy said that he had admired my integrity during the Army-McCarthy hearings…He then suggested that I now show my integrity by repudiating the Army position. He wanted me to join with him in some sort of statement which, he believed, would help him reestablish himself. He did not explain how if one show of ‘integrity’ repudiated another show of ‘integrity,’ either could be believed…‘It’s no good, Joe,’ I said. ‘It won’t work. It’s over and finished; that’s all. You can’t change the truth’…After about an hour, I got up to leave. McCarthy walked with me to the door and stood there until I reached the sidewalk. I said, ‘So long, Joe’ to the cadaverous visage of McCarthyism, standing silently in the shadows, slowly dying.” McCarthy’s visit with Adams, his call to Pearson, and other belated bids for forgiveness all were on his terms. There is no evidence that he was thinking about the damage he’d wrought with his Red-baiting of the State Department and Army. And he was too busy feeling sorry for himself to have second thoughts about his victims, or even to acknowledge that his crusade against communism had generated casualties.

On April 28, 1957, Joe McCarthy checked into Bethesda Naval Hospital for the last time, for what was said to be treatment of an old knee injury. His 12th-floor room was under guard, with wife Jean the only visitor allowed, and much more than a knee was ailing him, as is evident in hospital records made available to this author. Since a previous admission in January, McCarthy’s alcohol consumption had skyrocketed from “1/5 a day of whiskey” to “4/5’s a day.” His food intake had plummeted from “3 well rounded meals a day” to just beef broth. In late February “he began to have severe AM nausea & vomiting” along with “watery diarrhea,” his doctor wrote, and “this past 2 weeks he has been maintained on daily IV feedings—1500-2000 cc/day—Dextrose & H2O.” McCarthy’s liver was enlarged, he was jaundiced, his temperature was spiking, and he’d been sedated even before arriving at the hospital.

Once their patient was admitted, doctors were by his bedside regularly and nurses were present non-stop, on “special watch,” taking notes on every occurrence in a way that made clear Navy brass knew not just how sick the senator was but how controversial. “Patient was looking up at me and all of a sudden threw up his hands. I took them in mine, and I noticed his eyes rolled back and his face and shoulders were getting very flush. He started to gag and I then noticed patient going into what seemed like a Grand [Mal] Seizure,” a nurse wrote the morning of April 29. “At first very hard jerks all over and then completely all over came to a calm, complete calm. I [immediately] got on the bed and began artificial respiration, patient started to breathe again.” Four hours later McCarthy had another seizure and “there was difficulty in getting tongue blade in mouth.”

That evening, after further convulsions, Joe “bit his tongue. He then began body tremors involving his arms, head, & the muscles of his chest, & abdomen & his legs.” He was hallucinating, soiling his bedclothes, venting a pneumonia-like rattle from his chest, and excreting blood-red urine.

Nurses tried to decipher his muttering. “I want to go home… [I] haven’t had a drink in two or three weeks…only a few beers.”

Later, he seemed to be making a “speech” where he “keeps addressing ‘Mr. President.’” He talked about “going to work, his duties to investigate.” What caregivers could make out most clearly was when he “stated he had a new baby and it was his life.”

The watch continued as Joe restlessly picked at his oxygen tent, then clapped his hands and began laughing. He waved his arms overhead “as if to ward off attackers, mumbling incoherently, ‘Get away, get away.’” On day five, he “seemed very hot to the touch.” His temperature registered 106 degrees, then an even more alarming 110. “Packed in ice chips,” his nurse recorded at 4 p.m. “Nasal oxygen started. Color ashen.” A Catholic priest delivered last rites. At 5:45 p.m., three doctors worked in tandem to administer artificial respiration. The nurse’s last entry was at 6:02 p.m. that Thursday, May 2, 1957: “Respiration ceased. Pronounced by Dr. Kenny.”

Nobody close to him was surprised by Joe McCarthy’s death. Members of his inner circle had known long before his final visit to Bethesda Naval that his fall from political grace had shattered his heart and that liquor was eating at his liver. Joe’s refusal to eat—or to stop drinking—suggested he’d lost the will to live. What is less clear is what actually killed him that perfect spring day in May. His doctors and his death certificate gave the reason as acute hepatitis, “cause unknown.” FBI files show reports of everything from bone cancer to a slow poisoning by radiated water, or arsenic, or carbon tetrachloride. Some said the Soviets did him in; others blamed the CIA. The senator’s widow was reported to be telling relatives she suspected foul doings. “The day that [Joe] died, [Jean] went to the hospital to pick him up, because he was feeling good, he was coming home,” Mary Reardon, Joe’s cousin, said Jean McCarthy confided to her mother. “He had his things packed and was ready to go home. And she went to the bathroom and to finish up some things at the desk, and when she came back, there were three men leaving his room. And when she got there he was dead.”

While such theories of intrigue befit the author of America’s grandest conspiracies, they simply aren’t true. Nurses, corpsmen, or physicians were by the senator’s side continuously, making it nigh impossible for an enemy to do him harm. He didn’t have cancer, and nothing indicates he was poisoned with arsenic or anything else. Yet McCarthy’s hospital records do make clear one thing: he didn’t die from hepatitis. Tests showed only modest elevations of the compound bilirubin in his blood and of the time his blood took to clot, two indications of mild liver disease, and there’s little reason to believe that Joe’s mild-to-moderate form of that ailment killed him. The immediate cause of Joe’s death, say four of America’s most distinguished doctors who recently reviewed McCarthy’s files, almost certainly was the fever that spiked to deadly levels. That fever probably was triggered by severe symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, with seizures and delirium tremens, or DTs, which in that era killed a third of alcoholic patients. An infection—in McCarthy’s urinary tract, around a catheter in his bladder, or in his lungs—could have aggravated his DTs and contributed to that sky-high body temperature. So could Joe’s diseased liver, or even the newfangled anti-psychotic medications he was prescribed to control his agitation; such sedatives can interfere with temperature regulation and in rare cases lead to a fatal condition called neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

How could Joseph McCarthy’s team of esteemed Navy doctors seemingly get this final judgment on the senator from Wisconsin so wrong? If McCarthy’s demise had grown out of his DTs, as his hospital records suggest, the medical world had failed to appreciate the risk that condition posed or to treat his particular case as effectively as can be done today, when the mortality rate for DTs is under 5 percent. If neuroleptic syndrome did play a role, McCarthy’s physicians wouldn’t have known it; the first such episodes were only then being described, and in France. The syndrome was not widely recognized until the 1970s. If the senator had contracted pneumonia or some other deadly infection at Bethesda Naval Hospital, that facility’s staff lacked access to current-day drugs and technology that might have saved him. Most likely hepatitis was the acceptable “vanilla” verdict for a man whose liver was diseased. The gesture of invoking hepatitis—especially with the scary modifier “acute,” and absent the more accurate labels of alcoholic hepatitis or alcoholic cirrhosis—spared the McCarthy family the pain of publicly acknowledging Joe’s chronic and perhaps suicidal drunkenness. A concerted cover-up seems improbable, since the Bethesda Naval medical team requested an autopsy, which Jean McCarthy vetoed.

Tributes to the senator poured in from both sides of the McCarthy divide. President Dwight Eisenhower extended “profound sympathies” to Jean over the loss of the senator who’d branded him an appeaser. William Loeb, publisher of New Hampshire’s right-wing Manchester Union-Leader, insisted Eisenhower was one of Joe’s murderers, along with the communists. “No comment at all,” Dean Acheson, the former secretary of state who McCarthy had branded “Red” Dean, said. “De mortuis nil nisi bonum.” (In English, that Roman aphorism reads, “Of the dead, say nothing but good.”) Annie Lee Moss, a communications clerk targeted by McCarthy in his probe of the Army, said she was sorry to hear of her inquisitor’s death. “But that’s something we have all got to do sooner or later,” Moss added. The New York Times led with an obituary, along with two full pages of retrospectives, but no editorial. “Why dignify the bastard?” editor Charles Merz explained later. “Let him pass from the scene without more attention.”

Neither the Roman Catholic church nor the U.S. Senate appeared to have any such qualms. On Monday, May 6, a pontifical high requiem mass took place a few blocks from the White House at St. Matthew’s Cathedral, where four years earlier Jean and Joe had wed. As 2,000 mourners listened, Monsignor John J. Cartwright said McCarthy’s role in raising an alarm about communism “will be more and more honored as history unfolds its record.” Later that day, Joe was memorialized in the chamber of the Senate that he had joined at 38 and where, in 1954, colleagues had voted overwhelmingly to denounce him. The last Senate funeral had been William Borah’s in 1940, although leaders were quick to point out they would have done the same for any member whose family asked, as Jean had. “This fallen warrior through death speaketh,” said Chaplain Frederick Brown Harris, “calling a nation of free men to be delivered from the complacency of a false security and from regarding those who loudly sound the trumpets of vigilance and alarm as mere disturbers of the peace.” Seventy senators were on hand, along with Jean Kerr McCarthy, three of Joe’s siblings, Vice President Richard Nixon, Federal Bureau of Investigation Director J. Edgar Hoover, and McCarthy protégé Roy Cohn.

The next day Joe’s body, accompanied by three of his closest Senate pals, was flown by military plane to Green Bay, Wisconsin, then driven 32 miles to Appleton. Disciples came in flocks that sun-baked Tuesday, packing the pews at St. Mary’s and spilling onto the streets outside the Irish-American parish where Joseph Raymond McCarthy had been baptized and, six months shy of 49, was being eulogized. “Senator McCarthy was a dedicated man, not a fanatic,” Father Adam Grill said. “The guidance of our beloved land is under the guidance of human beings and as human being[s] we are all fallible.” Flags across Appleton were at half-staff, as they had been at the White House and other public buildings in Washington, and in Appleton schools and shops were shuttered at midday. This was the last of three memorials and the first in the state that had easily and repeatedly elected McCarthy to state and national office; 25,000 friends and fans from Green Bay, Neenah, and McCarthy’s native Grand Chute had paid their respects at his open casket. Others were keeping vigil outside the church alongside honor guards of military police, Boy Scouts, and Knights of Columbus members. On hand were 19 senators, seven congressmen, and a handful of other luminaries, most of whom had supported Joe in his relentless assault on communism.

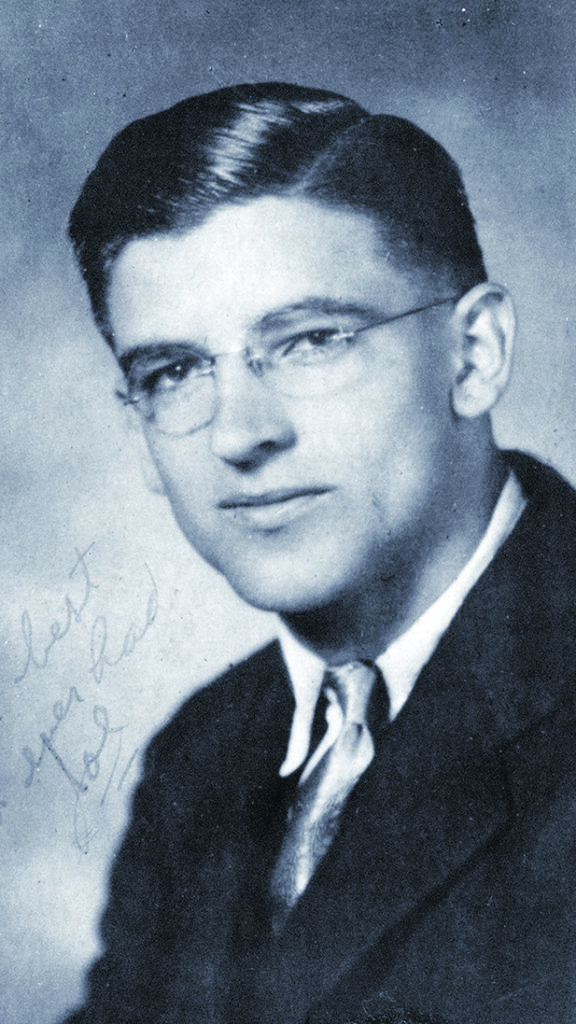

Joe McCarthy was buried in St. Mary’s cemetery, at his favorite spot on a tree-lined bluff overlooking the Fox River. As a rifle squad of U.S. Marines and Catholic War Veterans members fired triple volleys, Jean stood at attention. The casket was lowered into the ground between the graves of Joe’s parents, Timothy and Bridget, where a simple stone would read: Joseph R. McCarthy, United States Senator, Nov. 14, 1908–May 2, 1957.

Newspapers around the world ran obituaries, and commentators weighed in from the right and the left. The one who came closest to capturing the enigma—and the tragedy—of the Wisconsin senator may have been Eric Sevareid of CBS, one of the crusading wartime correspondents dubbed Murrow’s Boys. McCarthy “was a sudden rocket in the sky, enrapturing some, frightening others, catching millions in a kind of spell that dissipated only when the rocket itself, as a rocket must, spluttered, went cold, and fell…” Sevareid said. “If history finds that McCarthy used his strength in a wrongful manner, it will find that the weakness of others was part of the fault.”

_____

Excerpted from Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy copyright © 2020 by Larry Tye. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved.

This story appeared in the August 2020 issue of American History.