“Without thinking about it or having time to be scared, I crawled back to the open hatch, crouched in front of it, and rolled out.”

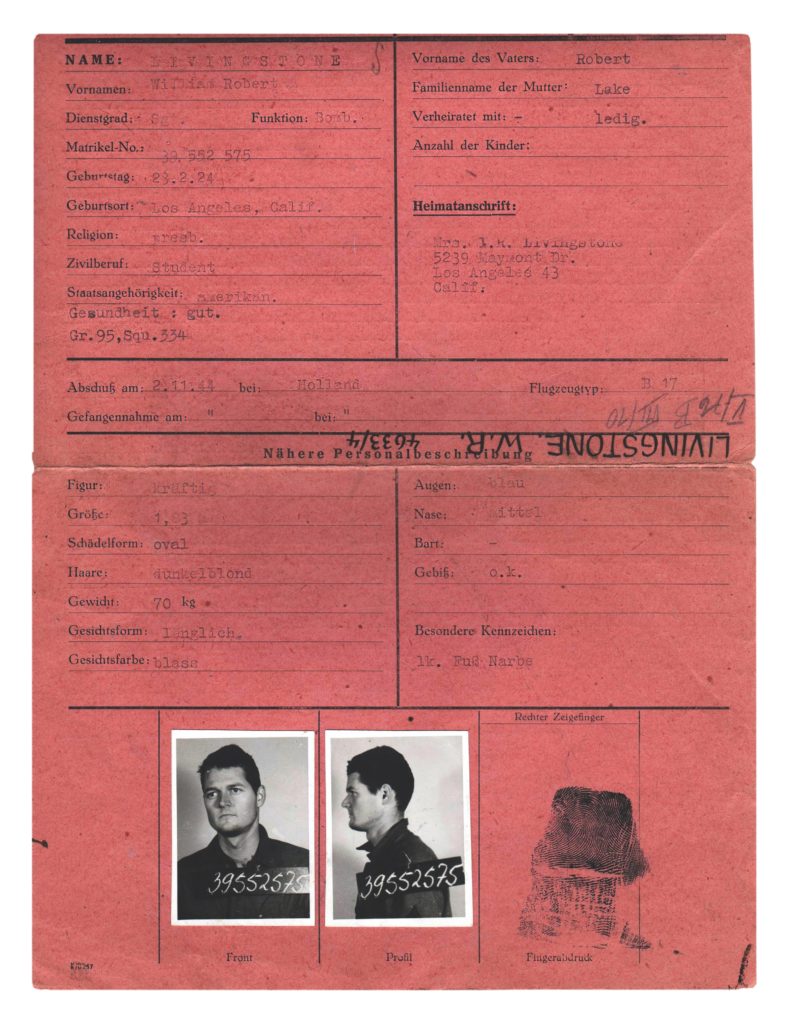

WITH TWO OF FOUR ENGINES shot out by antiaircraft fire, our B-17G, Ole Worrybird, sank slowly away from the rest of the 334th Bombardment Squadron and fell farther and farther behind. Those guys are flying home to England, I thought, but will we make it? We had just completed a bombing mission and were still over Germany. Soon, the remaining 95th Bombardment Group aircraft disappeared over the horizon. It was about half past noon on November 2, 1944—my date of infamy.

Our pilot, First Lieutenant Bill Pozolo, came over the intercom and made a roll call; he wanted to know if everyone on his crew was OK. Each answered in the affirmative until he called the tail gunner’s name. No answer. The pilot called again. Still no answer. The closest crew members—the waist gunners—could not see the tail gunner unless they crawled on their hands and knees back into the plane’s narrow tail section.

“Leo,” I heard the pilot say, “go back and see if he’s OK.” Staff Sergeant Leo Moser was a waist gunner, and a big guy.

“Roger,” I heard Leo reply over the intercom, and he crawled back into the tail section dragging a portable oxygen bottle. In about a minute, he came back over the intercom. This time, in a strained voice, he said, “Waist gunner to pilot, he’s gone.”

“What do you mean, gone?” the pilot asked.

Leo’s voice cracked as he almost shouted, “My God, man, he got hit by flak; he’s dead.” I learned later that Leo had, at great difficulty, dragged the tail gunner, Staff Sergeant James Martin, from the narrow space back to the waist section to see if he could tend to his wounds.

Our pilot responded with a steady voice. “Take it easy, everybody. We’re going to be OK.”

Even after more than 75 years, the details of that flight, and the events that led up to it, remain etched in my memory.

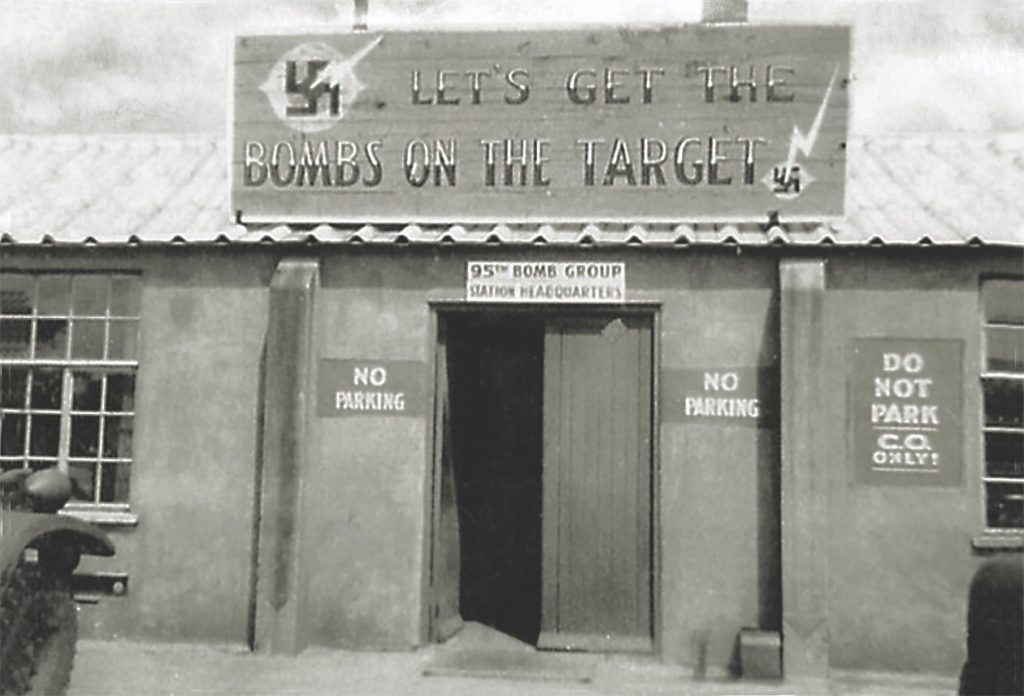

TWO DAYS BEFORE, on October 31, an orderly entered the Quonset hut where I was dozing at the 95th Bomb Group’s base—Station 119 at Horham Airfield in Suffolk, England. “Hey, Livingstone,” he said. “Wake up.”

I rose on one elbow and shook the sleep out of my head. “Yeah?”

“The major wants to see you.”

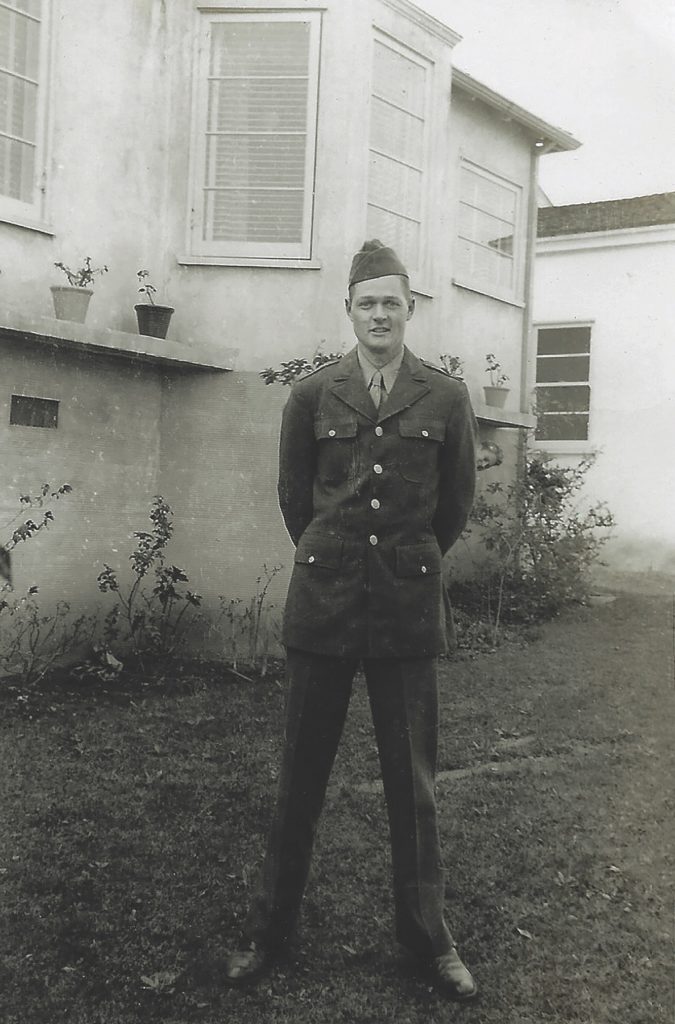

I had joined the 95th Bomb Group about a month prior to be an aerial gunnery instructor. But aside from a week spent training on a new gun site at a Royal Air Force base near Bath, I had killed all my time goofing off—bored as I waited for the “training equipment” that someone said was set to arrive from the States. I later learned that “gunnery instructor” was a euphemism for “replacement gunner.” That was a little scary, but I actually looked forward to flying a mission.

Major Harry M. Conley, commander of the 334th Bomb Squadron—a tall, good-looking Gregory Peck-type fellow—said, “Sergeant Livingstone, the nose gunner on Willis Pozolo’s crew is sick. I’d appreciate it if you’d volunteer to fill in for him for one mission.”

“Yes, sir,” I replied—enthusiastically, as I recall.

The major looked relieved. “Good. Go to supply, get a flight suit, and report to the briefing room at oh-five-hundred tomorrow morning for a practice mission, and you’ll fly a combat mission with the Ole Worrybird crew day after tomorrow.”

“GENTLEMEN, today the 95th’s target is the Leuna oil refinery at Merseburg.”

With the briefing officer’s words arose groans of trepidation from the 350 airmen jammed in the cigarette-smoke-filled room early on November 2. They faced little danger from enemy aircraft by that time in 1944, but heavy antiaircraft protection on the ground made Merseburg the second-most feared target in Nazi Germany; Berlin was the first.

At dawn, our “big-ass bird,” as we affectionately called the B-17, with its four 1,200-horsepower Pratt & Whitney radial engines, roared down the runway and lifted into England’s perennial overcast.

For the flight, I was bundled in a leather helmet, a fleece-lined jacket, pants, and flight boots, all of which I donned over an electrically heated suit. Under that, I wore my regular olive-drab wool Army Air Forces uniform and long johns. On top of all that was my chest-pack parachute and harness, and, finally, my flak jacket and dishpan-shaped flak helmet. Plus, of course, my oxygen mask. No, I wasn’t too warm, because, at the altitude of 29,000 feet, the temperature was 41 degrees below zero. There was certainly no cabin heat in those days.

I sat on a stool at the very front of the plane with the Plexiglas nose cone nearly surrounding me. I was not only the nose gunner; I was also the togglier—the guy who flipped the toggle switch that dropped the bombs. (Only our squadron’s lead plane had a bombardier.)

After nearly five hours of flying over a dense cloud cover, I heard our pilot’s voice over the intercom: “Pilot to togglier, time to ready the bombs.”

“Roger,” I responded and, after connecting my oxygen mask to a “walk-around” oxygen bottle, headed back to the narrow catwalk running through the center of the bomb bay. I leaned away from the catwalk toward the noses of the 10 500-pound bombs that hung on each side, one above the other, and with pliers in hand removed the cotter pins that prevented the bombs from arming accidentally.

That job being accomplished, I made my way back to my picture window in the sky. The only thing that had changed during the 10 minutes it took to arm the bombs was that the clouds below were now quite thin, and I could make out features on the ground, such as rivers and forests.

At about 15 minutes before noon, I noticed a small dark cloud directly ahead of us, and I heard the pilot say over the intercom, “Flak, twelve o’clock.”

The little cloud—rectangular and rapidly getting closer—was actually hundreds of puffs of black smoke: antiaircraft shells exploding at our altitude and directly in our line of flight. The 95th Bomb Group had to fly right into that box of flak to reach our planned bomb-drop zone. Just before we entered this “cloud,” the pilot announced, “One minute to bombs away,” and we were suddenly in it—black puffs of smoke all around us.

I remember thinking: this is just like the newsreels I’ve seen at movie houses for the last two years. At one point I heard what sounded like a paper bag pop, and the flak jacket I had laid over the lower part of the Plexiglas nose cone flopped back over my right foot. There was a small hole in the Plexiglas; I quickly put the flak jacket back in place.

At that moment I glanced back at the navigator, First Lieutenant Bob Strachan, a veteran of 24 combat missions (he, too, was filling in for this mission). He was crouched on a couple of flak jackets and had a couple more draped over his head. I, on my first mission, sat up there in the nose cone dumb and innocent, watching the action all around me.

The intercom crackled and I heard, “Pilot to togglier, open the bomb bay doors.” I flipped the bomb bay door switch and reminded myself not to be distracted—to keep my eyes on our squadron’s lead plane.

After what seemed like forever, but was probably about 60 seconds, I saw the smoke flare signal drop from the lead plane’s bomb bay. I put my finger on the bomb toggle switch.

Shortly, there they were: 10 bombs dropped from the lead plane’s belly. I flipped the toggle switch. Ole Worrybird instantly became two-and-a-half tons lighter, and I felt the force of gravity on my seat as if we had hit an air thermal updraft. Our entire squadron immediately banked hard to starboard to escape the flak zone; in 30 seconds, we emerged. What a relief.

A couple of minutes later, though, I realized we were about 1,000 feet below—and dropping behind—the rest of our squadron. The pilot came over the intercom: “Attention crew. We’ve lost number one and number three,” he said. I quickly looked at the number-one engine: the propeller was feathered and motionless. As I turned to look at number three, the pilot said, “They must have hit a hydraulic line. I can’t feather number three. It’s windmilling.” Bad news. A windmilling propeller causes drag and slows the plane down. That’s when the pilot called roll.

Because our radio operator, Tech Sergeant Tony Capone, had to maintain radio silence so as not to give away our position to enemy aircraft, he could not call for help. But two P-51 Mustang fighters spotted us falling behind and started doing “lazy-eights” over Ole Worrybird to fend off any enemy fighters.

About then, Ole Worrybird’s entire electric system shorted out. We could no longer communicate over the intercom, use the radio, or fire the electrically operated .50-caliber machine guns. Even worse, superchargers on the two remaining engines no longer operated. Ole Worrybird sank to about 2,500 feet, and our airspeed dropped to 100 miles an hour.

I learned later that at one point, while we were flying through the flak and taking evasive action, the waist crew thought we were going down and tried to open the escape hatch in the waist section but could not. Trapped, they decided to completely drop the ball turret, leaving a four-foot diameter hole in the bottom of the plane; bailout through that would be easy. Tony Capone, the radioman, had been sitting on the radio room floor with his feet dangling through that hole when Leo Moser shouted—mistakenly—“We’re out of control. Jump,” and Tony slid out into thin air. Their shock lessened just slightly when they saw his parachute bloom.

WITHOUT GUIDANCE from an electric compass, the navigator, Bob Strachan, was unable to tell the pilot exactly where we were. He looked out the windows and then back to his charts a number of times, trying to figure out our location by comparing the configuration of the small towns, rivers, and roads below us to those on his charts.

At about 1 p.m., half an hour after we dropped our bombs, the two escort P-51s ran low on fuel. They dipped their wings and sped toward England while we struggled on behind over the plains of northwestern Germany. Seeing them fly away left me with a strange feeling of loneliness. Soon the two fighters were out of sight.

Fifteen minutes later, our pilot spotted a small airstrip and decided that because we were flying so low, it would be better to land and be taken prisoner than risk being shot down over the front lines. Most ground fighting at that time was in Holland and Belgium, not Germany. And, of course, there was the possibility we might avoid capture.

While we repeatedly circled over the little airstrip, our pilot told the crew chief, Tech Sergeant Raymond Hill, to crank down our landing gear. One wheel cranked down easily, but the other was jammed; it wouldn’t budge.

Meanwhile, when it became apparent to the rest of us that our pilot planned to land, I signaled to Strachan that the highly secret Norden bombsight should be destroyed first. I did this by pointing my right index finger with my thumb up, like a pistol, at the bombsight. Bob shook his head and pointed to his hip, where he might have carried a pistol, but there was none. Sometime earlier in the war, the Army Air Forces had determined that its officers’ Colt .45s got them into more trouble than out of, and they no longer carried them into combat. But Bob agreed with me, and he signaled for me to go back to the escape hatch at the rear of the plane’s nose section. He unbolted the bombsight and handed it to me; I opened the hatch door against the wind stream and dropped it. I remember watching it grow smaller and smaller until it disappeared.

I started to crawl back toward the front of the nose section; over the engines’ roar I heard Bob shout, “Bill.” When I looked up, he pointed behind me. I looked over my shoulder and saw our copilot, Second Lieutenant Bart MacNeill, crouched in front of the hatch door I had just closed. He pulled the red jettison handle; the hatch door flew off and Bart rolled headfirst out into thin air. When I looked back at Bob, he signaled me to follow MacNeill on out.

I had no idea what was going on, or why the copilot had bailed out. But without thinking about it or having time to be scared, I crawled back to the open hatch, crouched in front of it, and rolled out. That was when I became aware of what had happened.

As I fell headfirst, I looked toward my feet and saw Ole Worrybird beyond them, perhaps 100 yards away, nosing down at a 45-degree angle. Flames were trailing from the right wing back to the tail assembly. Beyond the plane, I saw the belly of a German Focke-Wulf Fw 190 pull up from what must have been at least a second attack on our plane. The crew, the majority of whom had successfully completed 16 combat missions, now dropped out of Ole Worrybird like peas out of a pod.

I’m plenty clear of the plane, I thought; there’s no reason to count to 10 like they’d taught us in gunnery school. I grasped the aluminum handle on the front of the chest pack and gave it a hard yank. The chute trailed above me as I continued to fall headfirst. It quickly blossomed open with a loud pop. The sudden stop whipped me around with a violent jerk, and everything went quiet.

With an almost morbid fascination, I watched our magnificent hunk of machinery as it angled ever more steeply toward the ground. Within 30 seconds it crashed into a hedgerow about a half-mile away and exploded in a great ball of flame and black smoke. What a humiliating end to such a proud airplane.

WITHIN A COUPLE OF MINUTES, my feet, butt, and head hit the ground hard. I thought about how lucky I was to be still wearing my flak helmet. I rolled onto my stomach, reached my knees, collapsed my chute, and stood up in a large plowed field with no cover in sight.

After the bailout, the seven Ole Worrybird crewmen—minus James Martin and Tony Capone—were strung out on the ground fewer than 100 yards apart, close enough to exchange shouts. I heard my downwind neighbor yell that the man beyond him, the first to land, was hurt. I passed the word along and jogged over to where our copilot, Lieutenant MacNeill, with a look of disgust on his face, lay on the ground with a broken leg. Injuries like this rarely happened, even for first-time bailouts without paratrooper boots.

We quickly gathered around our fallen copilot and were discussing what to do next when out of nowhere, a grizzled little old farmer ran up to us, waving his arms and shouting in either German or Dutch. We couldn’t understand his words, but we had no trouble understanding his frantic gestures: he wanted us to get the hell out of there. He didn’t want us to get caught on his farm, I suppose, where he might be suspected of aiding the enemy.

We still didn’t know where we were—Germany, Belgium, or Holland—so I held up my hands to the farmer to stop his jabbering. I pointed in a northerly direction and said, “England.” Then I pointed toward the west and said, “France.” Finally, I pointed straight down at the ground and asked, “What is this?”

He didn’t understand those words, but he certainly understood what I wanted to know, because he turned his shriveled-up face to me and said, “Geermony!”—his way of saying, “Deutschland” in English.

Here we were at two in the afternoon, in enemy territory, with no cover or hiding place in sight. We hadn’t figured out yet what to do about Lieutenant MacNeill when we saw a dust cloud rising behind a motorcycle and a small, camouflage-colored panel truck bounding across the plowed field in our direction. Someone said, “That’s it. We’ve had it.”

The vehicles came to a stop 30 feet from us, and a dozen German Wehrmacht soldiers spilled out of the back of the truck, their rifles pointed. They shouted, “Oben, oben!” Clearly, they wanted us to raise our hands. This we did, in complete surrender.

Quickly a small crowd of civilians gathered to look at the “Yonkee Schreckenfliegers” (Yankee Terror Flyers). Because we had spent about 10 minutes circling the small landing field, they had had plenty of opportunities to see us bail out of the burning Ole Worrybird. At first, I was concerned, as I knew how angry German civilians were about the Allied bombing of their country. But more curious than hostile, these country folk—unlike the Germans who lived in cities—had been mostly isolated from the terrible destruction of war.

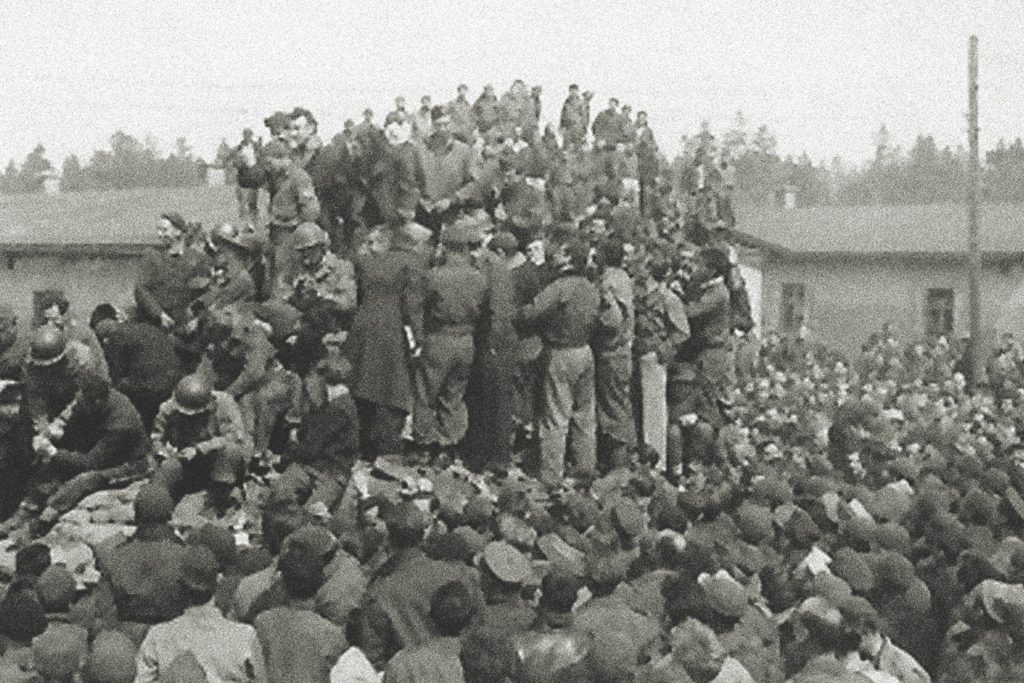

Finally, the soldiers put our copilot in the motorcycle’s sidecar and took him away to a hospital. They made the rest of us gather up our parachutes and marched us down a country road. After about three miles we came to a small Wehrmacht garrison, where we officially started our tour as prisoners of war.

That night, billeted in a cold damp stable, the remaining six of us discussed our fate and retraced the last flight of Ole Worrybird. I and the others spent the next six months in various POW camps in Nazi Germany. It was at our final camp, Stalag VII/A near Moosburg in southern Bavaria, that one of our crewmen crossed paths again with Tony Capone, whom I kept in touch with until his death in 2018. We were miserably housed, always hungry, usually too cold, but always knowing in the end that we would return home to our parents and loved ones. We just had to wait it out. The single day that got me there is the best-remembered out of all the days of my 96 years. ✯

This article was published in the October 2020 issue of World War II.