In 1899 the Boers handed the British Army three humiliating defeats in southern Africa.

ON OCTOBER 11, 1899, AFTER YEARS OF TRYING, CECIL RHODES FINALLY GOT THE WAR HE WANTED in southern Africa. Rhodes, the wealthiest man in Britain, perhaps even the entire world, had a heavily vested interest in a new outbreak of hostilities between Great Britain and the Boer republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State. Rhodes’s De Beers diamond mine in Kimberley controlled 90 percent of the world’s diamond supply, and after the discovery of fabulously rich gold deposits in Transvaal in 1886, he had joined forces with fellow diamond magnate Alfred Beit and other “gold bugs” to corner the market for that precious mineral as well.

With Rhodes’s encouragement, thousands of Britishers poured into Transvaal’s Witwatersrand region, known as the Rand. These uitlanders (outsiders), as the Boers, longstanding Dutch settlers in the region, called them, soon outnumbered the original residents three to one, creating a new boomtown at Johannesburg that almost overnight became the largest English-speaking city in Africa. The uitlanders, alleging ill treatment at the hands of the Boers, demanded that the British Crown intervene.

The uitlanders complained, not without reason, that the Boers had effectively disenfranchised them by severely restricting the voting rights of non-Boers. In addition, the Boers had imposed crushingly high taxes on the newcomers, with the revenues being diverted to other areas of the Transvaal. Most infuriating of all to the British miners was a tax on dynamite, an absolute necessity in their work. Rhodes, then serving as prime minister of Britain’s Cape Colony, added his considerable voice to the uitlanders’ demands. Both in public and in private Rhodes pressed the British government to more aggressively intervene. The fact that Great Britain had agreed by treaty to stay out of the political affairs of Transvaal and the Orange Free State did not seem to give him pause.

In late 1895 Rhodes went a step further by organizing a guerrilla raid on Johannesburg aimed at triggering a large-scale revolt by British immigrants there. The raid, led by Leander Starr Jameson, a top executive of one of Rhodes’s mining companies, was an abysmal failure. The Boers quickly rounded up Jameson and his men after they crossed the border from neighboring Bechuanaland, and the uitlanders in Johannesburg failed, at any rate, to rise up. Nevertheless, the raid dramatically worsened relations between Great Britain and the Boers. “The Jameson Raid was the real declaration of war,” Jan C. Smuts, a high-ranking Boer statesman and soldier, later observed. “The aggressors consolidated their alliance, the defenders on the other hand silently and grimly prepared for the inevitable.”

Faced with deteriorating political, social, and racial conditions in Transvaal, the republic’s formidable president, Paul Kruger, issued an ultimatum to Great Britain in early October 1899. Kruger demanded that the British and their South African colonies immediately cease interfering in his country’s affairs, remove their troops from the Transvaal border, and recall any military reinforcements that might be on the way from England. Otherwise, Kruger warned, he would “with great regret be compelled to regard the action as a formal declaration of war.” Though Kruger and his stolid countrymen had defeated British forces in the First Boer War 18 years earlier, the new ultimatum was met with near-universal derision in Great Britain. London’s mighty newspapers dismissed Kruger and his “impudent burghers.” “One is in doubt whether to laugh or to weep,” gibed the London Daily Telegraph.

There would soon be more weeping than laughter. After the expiration of Kruger’s ultimatum at 5 p.m. on October 11, some 38,000 Boer commandos swept on horseback across British-controlled Natal, Cape Colony, and Bechuanaland and put the major outposts at Kimberley, Ladysmith, and Mafeking under siege. British reaction back home was immediate. A 47,000-man relief corps led by General Sir Redvers Buller, one of the nation’s most decorated soldiers, was dispatched to Cape Town and ordered to head north to capture the Boer capitals of Bloemfontein and Pretoria. Britain would call the Boers’ bluff.

RHODE’S INEXPLICABLE DECISION TO RUSH TO KIMBERLEY IN THE FIRST DAYS OF THE WAR, rather than remain safely in Cape Town, drastically altered Buller’s battle plan before he ever set foot in Africa. Instead of heading straight to Pretoria and possibly bringing a speedy end to the war, Buller was forced to divide his army into three parts. The first would remain in Cape Colony to guard against further Boer incursions; the second, commanded by Buller himself, would march to Ladysmith, in western Natal; and the third, under Lieutenant General Paul Sanford Methuen, would relieve Kimberley in northeastern Cape Colony and stop the relentless stream of angry messages that Rhodes was somehow smuggling past the Boers to the highest levels of the British government.

Buller and Methuen, though experienced soldiers, shared a serious drawback: Neither had ever commanded large numbers of troops in battle. Buller confided his misgivings to the British secretary of state for war, Henry Charles Keith Petty-Fitzmaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne, before he left for South Africa. “I have always considered that I was better as second in a complex military affair than as an officer in chief command,” Buller said. “I have never been in a position where the whole load of responsibility fell on me.” What Lansdowne made of that remarkable admission is unknown, but he expressed his own doubts about Lord Methuen. “Paul Methuen is a great friend of mine,” Lansdowne told Buller, “but I doubt if he is man enough to run the show in the Cape.” These were the men the Crown had chosen to lead British soldiers into action against the Boers.

Methuen, for his part, entertained no such misgivings about his fitness for command—far from it. “I shall breakfast in Kimberley on Monday,” he airily announced when he set out from his Orange River base camp on November 21, sporting a jaunty bush hat, khaki trousers, and bedroom slippers. Methuen had reason to be confident. The youngest lieutenant general in the British Army, he had been educated at Eton and won his first commission with the Scots Fusilier Guards in 1864. He had served in Africa under General Sir Garnet Wolseley during the Ashanti War and the subsequent Egyptian campaign. But these were staff positions. His only experience as a field commander had come with a mounted rifle battalion in the bloodless Bechuanaland expedition of 1884–1885.

From the start, Methuen labored under serious tactical handicaps. As his experience in Bechuanaland should have taught him, a commander is only as good as his intelligence, and Methuen was hamstrung by his lack of good cavalry scouts. Major Michael Rimington’s colonial guides—known as the Tigers for the wildcat-skin bands they wore around their bush hats—were the best he had in camp, but they were no match for the native-born Boers, who were unmatched marksmen on horseback and had a killing range of 500 yards with their 7.63-caliber Mauser rifles. This made the Tigers understandably cautious, and their intelligence reports tended to be vague estimates rather than close observations of enemy strength and dispositions.

Methuen was further hindered by his need to hug the railroad as he inched along. Because he had few transport animals, the single track rail was his one lifeline to the coast; he and his troops couldn’t stray from it. The railroad ran straight into Kimberley, giving Boer observers the great advantage of knowing exactly where Methuen was at any particular time and where he was going next. They could pick their spots to attack.

The Boers chose to contest the British advance first at Belmont, 20 miles from the Orange River. On November 23, some 2,000 Free State commandos under Jacobus Prinsloo launched an ambush from the kopjes (hills) overlooking the Belmont railroad station. Several staff officers, fearing the worst, had advised Methuen to outflank the Boers. Methuen would have none of it. “I intend to put the fear of God into these fellows,” he told his chief of staff. He said he would attack head on, “trusting to the courage and stubbornness of our troops to gain the day.”

At daybreak, the Coldstream Grenadiers and Scots Guards charged into a volley of Boer bullets and clambered to the top of the hills while the Boers, as planned, fled down the rear to their waiting horses. The triumphant British raised an impromptu chorus of “Soldiers of the Queen.” One retreating Boer, unmoved by the serenade, thumbed his nose as he galloped away.

Two days later, at Graspan, 20 miles northeast of Belmont, the British again confronted a dug-in line of Boers on the high ground flanking the railroad. This time the Naval Brigade led the charge. “By Jove, what sport!” cried one young midshipman. Despite being picked off by the dozens, the sailors somehow managed to cover the 650 yards to the steep-sided kopjes through a hurricane of fire. Once again the British forces carried the high ground, only to see the Boers ride away unscathed.

In the two brief encounters Methuen had suffered nearly 300 casualties, including war correspondent E. F. Knight of the London Morning Post, who lost an arm to an illegal dumdum bullet. Dumdums—hollowed at the tip and covered with a piece of tin that shattered on impact, causing horrific wounds—had been outlawed by the recent Geneva Convention, but the Boers claimed that they had found a sizable supply the British left behind at Dundee. To the Boers’ unforgiving way of looking at things, they were simply returning the bullets to their former owners.

Though badly shaken by his losses, Methuen continued to advance toward Kimberley. When the British column pulled within sight of the Modder River on the morning of November 28, Methuen scanned the wide plain leading down to the water. “They are not here,” he remarked confidently to Major General Sir Henry Colvile of the Coldstream Guards. “They are sitting uncommonly tight if they are, sir,” Colvile replied uneasily. No sooner had he spoken than 3,000 Boer riflemen opened up from concealment behind the riverbank. All that Methuen’s men could do was fling themselves on the ground, cover up, and wait for darkness.

All day beneath a broiling sun, in temperatures that rose to 110 degrees, the surviving British soldiers lay as motionless as their dead brethren. The slightest movement would bring a bullet to the head, and the men did their best to ignore the blazing heat and the red ants that swarmed over them. The kilted members of the Sutherland Highlanders suffered blistering sunburns on the backs of their legs.

At nightfall the Boers again fell back, leaving the empty field to the British. For 12 days Methuen, who had suffered a superficial but painful bullet wound to the thigh, waited impatiently for reinforcements while his engineers repaired the Modder River bridge, which the Boers had dynamited when they fled. On the evening of December 9–10, Major General Andrew J. Wauchope and the Highland Brigade reached Methuen, and the next morning British artillery commenced bombarding the new Boer position at Magersfontein. Unbeknownst to the British, the majority of the shells passed harmlessly overhead while the Boers hunkered down in concealed trenches at the base of Magersfontein Hill. The trenches, three to five feet deep, were so well camouflaged by heaps of grass and acacia scrub that British scouts riding within a mile of the trench line could see nothing amiss. With Mauser bullets soon singing about their heads, they did not look for very long.

For the 4,000 men in the storied Highland Brigade huddled beneath thin blankets on groundsheets, it was a cold and cheerless bivouac—no smoking or fires allowed. Still, the kilted soldiers maintained their esprit de corps, even as they attached khaki-colored aprons to their tartan kilts and painted over their polished brass buttons and belt buckles to be less conspicuous to the Boer sharpshooters waiting ahead of them, somewhere in the dark. Three miles to the north lay the enemy position on the gray-green kopjes of Magersfontein, which they would attack at first light.

While Methuen and his 15,000 soldiers waited out the night near Magersfontein, a second, smaller British column led by Lieutenant General Sir William Gatacre advanced northeast to Stormberg, an important railroad junction linking East London and Port Elizabeth in Cape Colony to Bloemfontein in the Orange Free State. Gatacre, a fitness buff whose men called him, not unaffectionately, “General Back-Acher,” was a 35-year veteran of the military, having served with distinction in India, Burma, and the Sudan. Gatacre had commanded a division during the famed British victory at Omdurman, where a year earlier, under the command of Horatio Herbert Kitchener, the British had defeated a Mahdist force twice their size and reconquered Sudan. He was an experienced, energetic, hard-driving officer, and British newspapers confidently predicted that his new campaign would “astonish the world.”

That remained to be seen. The British had ill-advisedly abandoned the garrison in the southeastern district of Stormberg five weeks earlier; now Gatacre would have to retake it. He had at his disposal 2,600 crack troops: the Northumberland Fusiliers, the Irish Rifles, three companies of mounted infantry, two batteries of field artillery, and the 12th Company, Royal Engineers. The force moved by railroad to Molteno, eight miles south of Stormberg, on December 10 and set out on an all-night march across the pitch-black countryside.

Incorrectly informed that the Boers had placed barbed wire across the main road paralleling the rail line, Gatacre abruptly changed direction, depending for his eyes on a handful of Kaffir guides from the anti-Boer Fingo and Tambu tribes. But the guides promptly lost their bearings—intentionally, some skeptical British soldiers said—and Gatacre’s force wandered into the surrounding hills and gullies, missing a crucial turn. Compounding his error, Gatacre failed to alert his subordinate commanders of his change in plans. Instead of approaching Stormberg from the northwest, they went completely around the junction and ended up approaching it from the southwest.

Having marched all night over rough terrain, the men were hungry and exhausted. Gatacre, true to his nickname, ordered them to press on. Passing a Boer farm at Klipfontein, the troops aroused a watchdog. Its barking woke two sleeping burghers, who rushed to their guns and opened fire on the British from behind a low stone wall. Sixty Boer riflemen posted on a hill a mile away rushed to join the fight, as did other quick-responding villagers. Boer regional commandant Jan Henrick Olivier arrived on the scene with 800 reinforcements. The British troops, thinking they had reached Stormberg proper, floundered about in a large gully, taking fire from all sides in the dark.

Gatacre responded calmly, sending the Irish Rifles to seize a small hill on the Boer right. They did so, but the remainder of the British force charged directly up the main ridge, where Boer marksmen quickly shot down 89 men while losing only 34 of their own. The Northumberland Fusiliers, at the head of the column, tried to get around the ridge from the rear but ran into another approaching Boer contingent on the Molteno road. Believing themselves surrounded by a much larger enemy force, they abruptly hoisted a white flag. Nearly 700 British officers and men handed over their weapons to 50 astonished Boer commandos and townsmen.

Gatacre, unaware that the Northumberlands had surrendered en masse, fell back along the rail line to Molteno, having lost a third of his command in less than an hour. Buller, preoccupied with his own long-delayed approach to Ladysmith, received news of Gatacre’s defeat with remarkable equanimity. “Am sorry to hear your bad luck,” he responded. “You are right to concentrate; will reinforce you as soon as possible.” The next day, a much greater disaster would befall the British at Magersfontein.

THE FOUR SCOTTISH REGIMENTS IN THE HIGHLAND BRIGADE PICKED TO LEAD THE ASSAULT at Magersfontein were among the most famous fighting units in the British Army: the Black Watch, the Argylls, the Seaforths, and the Highland Light Infantry. Only four regiments in the entire army boasted more battle honors than the Highland Lights, who had been recruited not in the Highlands but in the urban slums of Glasgow. The soldiers in their brother regiments called them the “Glesca Keelies,” Scottish slang for Glasgow pub brawlers. The Highlanders adopted the nickname with pride.

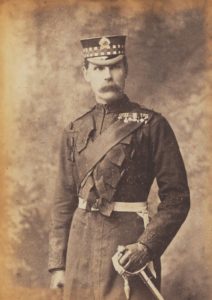

The men in the brigade were rested, confident, and battle tested. They placed complete faith in their commander, Wauchope, whom they called “Red Mick.” Tall, thin, and clean shaven (the only general in the army without facial hair), Wauchope was one of the richest men in Scotland, heir to a massive coal-mining fortune. At 53, he had followed the Union Jack for 34 years and had seen combat in four colonial conflicts in Africa: the Ashanti War of 1874, the Egyptian campaign of 1882, the Nile expedition of 1884–1885, and the Sudan campaign of 1898. He had been seriously wounded three times—once given up for dead—and he confided to friends that he did not expect to survive a fourth wound.

Nor did Wauchope share his men’s confidence about the planned attack. Having already attacked the Boers head on three times without success, Methuen proposed to do the same thing yet again. This time the Highland Brigade would take the lead. To shorten the distance they would have to cover, Methuen ordered Wauchope to march his men halfway to Magersfontein, camp on the open plain, and then creep as close as possible to the Boer position under cover of darkness. Methuen did not explain how he expected them to avoid being spotted by some of the best mounted scouts in the world.

Once his men were in position, Wauchope ate a cold roast beef sandwich and bedded down in his sleeping bag to wait for dawn. He had never been lucky in battle—his three wounds could attest to that—and his mood was further darkened by the fact that he had lost the new knife and compass his wife had given him before he sailed away to war. It seemed a bad omen.

At midnight on December 10–11, Wauchope was awakened by his staff. Against standing orders that officers not carry swords or other outward signs of rank that might attract Boer snipers, he picked up his well-used claymore, the traditional double-edged broadsword of the Scottish Highlanders, and headed for the front. His men were arranged in quarter columns. Ninety-six rows of soldiers stood shoulder to shoulder in a column 40 yards wide and 160 yards deep. To keep the column in close formation, two junior officers, one at each end of a line, held the ends of a long rope that acted as a guide. As quietly as possible, the 4,000 men headed into the darkness. The Black Watch took the lead.

Three hours later the gray face of Magersfontein Hill began to take shape 600 yards in the distance. Wauchope’s aide-de-camp, Major George E. Benson, whispered, “This is as far as it is safe to go, sir, in mass.” He assumed that the men would deploy in extended order, three lines of troops with a five-pace interval between each soldier. But Wauchope, concerned that the men would get lost in the thick patches of thorny bushes, replied, “I think we will go a little further.” But this was as far as most would get.

Before the Scotsmen could take another step, a torrent of gunfire erupted in their faces; an Argyll sergeant later recalled that it was as though “someone had pressed a button and turned on a million electric lights.” The astonished Highlanders froze in their tracks. Many of the Boers’ first shots went high, and Wauchope ordered the men to deploy and charge the enemy trenches. He turned to his cousin, Lieutenant Arthur G. Wauchope, and directed him to tell the Black Watch to extend their right. “This is fighting,” Wauchope told his young kinsman, somewhat unnecessarily under the circumstances.

Lieutenant Wauchope delivered the order to Lieutenant Colonel John Coode, the commander of the Black Watch. Coode tried to get the men moving again but immediately fell mortally wounded, as did Lieutenant Colonel Gerald Goff of the Argylls. Lieutenant Wauchope, returning to the front, found his cousin also lying dead, 200 yards in front of the enemy position, his trusty claymore by his side. The lieutenant soon fell wounded beside him.

Without proper leadership, the men of the Black Watch staggered across the exposed plain. One surviving Argyll Highlander recalled the chaos that ensued. “I remember distinctly the 91st [Argylls] getting the order to move to the right, and we started moving in that direction when several contractor orders rang out, some calling to ‘fix bayonets and charge,’ etc. Then the Black Watch, who were in front, could stand it no longer, and were driven back on the Seaforths, who likewise started to shout ‘retire’ and the next minute the brigade had lost all shape and were converted into a dismayed mob, running to seek cover and getting shot by the score as they did so.”

Sunrise revealed a plain heaped with prone British soldiers—dead, wounded, or dazed. For the next nine hours, in a grisly reprise of the Modder River debacle, the Scots and their compatriots hugged the scorching ground while Mauser bullets zinged overhead or thudded horribly into flesh and bone. Lieutenant Wauchope drew particular attention from Boer sharpshooters as he lay writhing on the ground. He was hit several times in both legs, injuries from which he never fully recovered.

At 9 a.m., Methuen committed his last reserves, the 1st Gordons. Advancing over the sprawled Highlanders, the Gordons made a series of charges across the 3,600-yard-wide plain. The closest they came was 300 yards before Boer riflemen drove them to the ground alongside their comrades. Methuen, watching through binoculars from a hillside several miles in the rear, found himself fresh out of ideas. “Hold on until nightfall,” he commanded.

After sundown the firing stopped and the plain grew silent except for the guttural groans of hundreds of wounded, thirst-crazed men. Even the Boers, not the warmest-hearted of foes, took pity on their enemy. They called out to one isolated remnant of the Black Watch and told the soldiers that if they left their arms and ammunition behind, they could get up and walk back to the rear unmolested. It was done.

Methuen clung to a minimal hope that the Boers would retreat again, as they had done at the Modder River. But this time the Boers remained in their trenches, observing the carnage they had wrought. The next morning ambulance drivers went out to gather the wounded and dead. They found 210 British troops dead and another 948 wounded. Of those casualties, 702 were members of the Highland Brigade, including General Wauchope, Lieutenant Colonel Coode, and 44 other officers.

Methuen ungallantly blamed Wauchope for the defeat, saying that Red Mick had not gotten his men to attack quickly enough. Wauchope’s men, in turn, blamed Methuen. “Everyone here is furious with Methuen for his bad generalship,” Lieutenant Bertram Lang wrote in a letter home. Another member of the Black Watch spoke for all the devastated Scottish soldiers at Magersfontein. The brigade, he said, had been “led into a butcher’s shop and bloody well left there.”

REMARKABLY, WORSE WAS STILL TO COME FOR THE BRITISH ARMY. Buller, telling Methuen to “fight or fall back” from Magersfontein, continued his advance toward Ladysmith. Twelve miles south of the besieged town, Boer commander Louis Botha had established a strong line of defense anchored in the foothills immediately north of the Tugela River. At Colenso, the most obvious crossing place on the river, Botha had stationed 4,500 men, with another 800-man force guarding Hlangwane Hill on the south side of the river. So exposed was the hill to enemy attack that Botha’s subordinates drew lots to see who would man the position.

Unnerved by the bad news from Stormberg and Magersfontein, Buller decided that he must attack immediately at Colenso. “Am coming through via Colenso,” he heliographed Lieutenant General Sir George White, the British garrison commander at Ladysmith. Like Gatacre and Methuen before him, Buller decided on a frontal assault. The four-foot-deep Tugela River zigzagged between steep banks; the British soldiers would have to cross a triangulated plain of gunfire to even reach the river. The unwelcome task was given to Major General Henry J. T. Hildyard and his headquarters brigade. “May the Lord have mercy on our souls,” someone murmured on hearing the plan.

Certainly the Boers would not show much mercy. At 5:30 a.m. on December 15, British naval guns began bombarding the Boer defenses with recently developed high-explosive lyddite shells, which were designed to pierce armor but would prove relatively ineffective against dispersed ground forces. Buller, wearing a peaked cap and riding breeches, stood directly behind the gunners, watching the bombardment through a telescope. Almost immediately he could tell that something was wrong. Major General Fitzroy Hart, commanding the Irish Brigade, had been ordered to cover the British left, fording the river at Bridle Drift, three and a half miles southwest of Colenso, and head east. Instead, misinformed by his non-English-speaking African guide, Hart veered right and marched his men into an open plain where the river looped north at Punt Drift. Four regiments—the 2nd Dubliners, 1st Inniskillings, 1st Connaught Rangers, and Border Regiment—marched into the narrow loop on a beautiful clear morning that reminded the men of an Irish June. It was, however, nothing short of a killing zone.

Some 300 yards away, the Boers waited patiently in their trenches. When all four British regiments had entered the loop, they opened fire with their Mausers and shrapnel-loaded Krupp artillery.

A sound that resembled hail dropping on a glass roof swept across the field, and the entire first line of Irish infantry went down. Confusion reigned. Some of the men lay flat on the ground; others broke for the rear; still others, disoriented, dashed heedlessly right or left. Captain Cecil F. Romer of the 1st Dubliners described the melee: “Nobody knew where the drift was. Nobody had a clear idea of what was happening. All pushed forward blindly, animated by the sole idea of reaching the river bank.” Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Thackeray, commanding the Inniskillings, found a way out—a clear path to Bridle Drift that had high banks to shelter the men from enemy fire. Hart angrily ordered him back into the loop.

Buller, watching from a nearby hill, sent numerous messages to Hart, telling him first not to enter the loop and once he had, to get out immediately. Meanwhile, the British center, 8,000 men strong, began its advance. Once again, things went wrong from the start. Colonel Charles Long, commanding the field artillery, had been instructed to remain well out of rifle range, at least two and a half miles back from the river. Instead, Long moved his 18 15-pounder and 12-pounder pieces to within 1,000 yards of the river. As historian Thomas Pakenham observed, Long was following “one of the great traditions of the British army: courage matched only by stupidity.” He soon paid for his stupidity with his life, shot through the liver by a Boer bullet. The battery’s other officers began falling as well. A disbelieving Buller shouted to a staff officer: “See what those guns are doing. They seem to me to be much too close. Tell them to withdraw at once.”

Mounting his charger, Buller rode toward the firing line. Staff officers dashed up to tell him that the entire field artillery had been knocked out of action. The commanding general located Hildyard near a wagon bridge. “I’m afraid Long’s guns have got into a terrible mess,” Buller said. “I doubt whether we shall be able to attack Colenso today.” Hildyard’s left flank, which Hart had been supposed to cover, had been left unprotected; the right, at Hlangwane Hill, had made no progress either. At 8 a.m., less than two hours into the attack, Buller called off the entire operation. “Hart has got into a devil of a mess down there,” he told Hildyard. “Get him out of it as best you can.”

Buller rode along the lines, oblivious to the whizzing bullets and shrapnel all around him. “Steady, men,” he called out. “Don’t lose your heads.” When a shell fragment hit him in the ribs, Buller told his doctor that it “had only just taken his wind a bit.” On the open plain ahead, 12 of Long’s field guns lay abandoned, their panic-stricken horses still tied to the traces. “Now, my lads, this is your last chance to save the guns,” Buller called out. “Will any of you volunteer to fetch them?”

A handful of soldiers and junior officers stepped forward, including Lieutenant Frederick H. S. Roberts, son of British field marshal Frederick Sleigh Roberts. Mounting up, they dashed toward the guns, disappearing in a storm of bullets and dust. Somehow, Captain Harry Norton Schofield and a corporal managed to bring back two 15-pounders. Freddy Roberts had taken a mortal wound in the stomach. Buller cabled his father in Ireland with the crushing news: “Your gallant son died today. Condolences. Buller.”

To Landsdowne, the British secretary of state for war, Buller sent a less personal but equally despairing cable: “I regret to report serious reverse. I do not think I am now strong enough to relieve White. Colenso is a fortress, which I think, if not taken on a rush, could only be taken by a siege.” Winston Churchill, then a young war correspondent, concurred. “If Sir Redvers Buller cannot relieve Ladysmith with his present force,” he wrote, “we do not know of any other officer in the British Service who would be likely to succeed.” Buller would not get a second chance. Three days later Lansdowne relieved Buller, Methuen, and Gatacre from command. Taking Buller’s place was the grief-stricken Lord Roberts.

The shocking defeats at Stormberg, Magersfontein, and Colenso completed the infamous “Black Week” for Britain and its vaunted soldiers. In London, crowds of stunned citizens heard newsboys calling out the headline: “Terrible reverse of British troops! Loss of 2,000!” Shops, theaters, and concert halls remained largely empty during the Christmas season. American author Mark Twain, who happened to be staying in London at the time, observed the stricken mood. “It’s awful here,” Twain wrote a friend back home. “Half of our friends are in mourning, and the hearts of the other half stop beating when they see a newsboy. This is a sordid & criminal war, & in every way shameful & excuseless.” Meanwhile, Roberts, wearing a black arm band in mourning, left immediately for South Africa in advance of a massive influx of reinforcements. Exactly two months after the British defeat at Colenso, he succeeded in breaking the Boers’ 124-day siege of Kimberley and liberating Cecil Rhodes and 42,000 less-exalted soldiers and civilians trapped there.

In a clear sign of precedence, the commander of the relief column, Brigadier General John French, reported first to Rhodes, not to Kimberley’s garrison commander, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Kekewich. Somehow, after four months of subsisting on horsemeat, mule meat, and brackish water, Rhodes managed to lay out a welcoming feast of champagne, cake, and caviar at his headquarters at the Sanitorium Hotel. When Kekewich arrived to report to French, Rhodes rushed forward and shouted, “You shan’t see French; this is my house, get out of it.” Actually, that wasn’t quite correct: technically, the hotel was owned by the De Beers corporation—but then, so was much of Kimberley, the Transvaal, and indeed all of South Africa. And Cecil Rhodes never let anyone forget it. MHQ

Roy Morris Jr., who lives in Chattanooga, Tennessee, is the author of nine books. While researching this article, he discovered that he is related to the doomed Lieutenant Colonel John Coode of the Black Watch.

[hr]

This article appears in the Autumn 2019 issue (Vol. 32, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: The Darkest Week

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!