[dropcap]L[/dropcap]ieutenant Colonel Doyle R. Yardley knew the answer to the question he had just been asked, but he damn well wasn’t going to answer.

The German panzer captain repeated the question. Yardley shifted slightly and stared back at his interrogator.

Again, the man asked, in perfect English, “What is your mission? Are more parachutists to be dropped?”

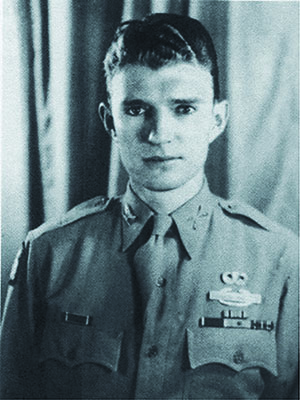

Eyeing the skull and crossbones insignia on the man’s black wool collar, Yardley said nothing. The 30-year-old commander of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion, a 1937 graduate of Texas A&M’s ROTC program, had no intention of cooperating.

Realizing the futility of repetition, the German changed tactics and gave Yardley a shot of whiskey followed by a cup of ersatz coffee. The two adversaries sipped their beverages and guardedly debated the war. While disagreeing over who would ultimately win, they both knew the latest Anglo-American assault in Italy was on the brink of disaster.

Yardley’s own operation was certainly off to a disastrous start. He had been in enemy territory for less than three hours before being wounded and taken prisoner. He had no information about the fate of his men. Nor did he realize that the mission had unraveled almost immediately after take-off and that the men of the 509th, falling back on their training, were being forced to improvise.

ALLIED FORCES HAD LANDED on the beaches of Salerno, in southwestern Italy, before dawn on September 9, 1943, but within three days their advance ground to a halt in the face of heavy German counterattacks. Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark, the American commander of the expedition, had underestimated the Germans’ pugnacity and deft reaction. Tanks and half-tracks filled with panzergrenadiers swarmed in, terminating what little inland progress the Allies had made. By Monday, September 13, the counterattacks were dangerously close to splitting the British and American sectors. On the verge of being thrown back into the sea, Clark realized his situation was precarious enough to consider evacuating his forces.

To avoid that outcome, the 82nd Airborne Division rushed reinforcements to the besieged beachhead. Two parachute infantry regiments dropped into the Allied perimeter over a period of two nights, with two more regiments arriving later by sea. Yet Clark needed more help.

Even before the landings at Salerno, Allied planners had envisioned a bold mission: dropping paratroopers 15 miles behind enemy lines to seize and hold an intersection of converging highways near Avellino, a bottleneck through which southbound German traffic passed en route to the beachhead. But the developing chaos of the landings provoked a series of confused orders and cancellations.

As a result, it was not until the afternoon of September 14 that Yardley’s 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion, temporarily attached to the 82nd, received orders to drop behind enemy lines that same night. The men had only six hours to get ready.

Veterans of combat jumps in North Africa—a campaign defined by improvisation—the men of the 509th were up to the challenge; after months of inactivity they were eager to get back into the war.

“One minute we were sitting, fat, dumb, and happy, on the beach,” Private Charlie H. Doyle, a teenager from Massachusetts, recalled. “The next, orders came down to prepare for action.”

The troopers were briefed to expect a fluid situation as soon as they hit the ground. There was little information about the enemy’s disposition; the Americans expected to encounter rear echelon troops, but reports indicated a panzer division was inbound from Rome and expected to pass through the crossroads. If General Clark’s forces did not break through to relieve the 509th in three to five days, the paratroopers were to split into small groups and make their way back to friendly lines.

As the paratroopers finalized their preparations, the reality of their potential exodus weighed heavily on them. The battalion surgeon, Captain Carlos C. “Doc” Alden, recalled thinking that “if we don’t come back, there will be thousands to take our place and win this war. I hope I make it, but I hope even more to do my duty as an American man.” The bespectacled Alden was well suited for service in the paratroops: before the war, he had been an athlete and an amateur daredevil, playing football at Princeton and roaring down Lake Placid’s bobsled run on his motorcycle.

At 9:35 p.m., the first of 39 C-47 aircraft, each carrying a “stick” of 16 paratroopers, lumbered down the dirt airstrip at Comiso, Sicily, and lifted into the night sky. In the pale light of a full moon, the transports flew in pairs along the Italian coast up to Agropoli, across the Allied bridgehead to Montecorvino, and into the steep valleys of the Apennine Mountains. Except for a few moments of moderate antiaircraft fire when the C-47s flew over the frontlines, the flight was relatively quiet. With the flak behind them, the planes droned on toward the drop zone—a valley near Avellino surrounded by 4,000-foot peaks.

JUMPING FROM THE LEAD AIRCRAFT, Doyle Yardley landed near Lieutenant Fred E. Perry’s 11-man pathfinder team. The pathfinders had jumped a mere 10 minutes before the main element and, with no time to relocate, set up their navigation aids—two Aldis lights and a 5G transmitter—where they landed, hoping the following aircraft would drop on their signal. Perry informed Yardley that they had come down at an intersection near the village of Santa Lucia di Serino—a mile short of the actual drop zone.

Still, as several C-47s buzzed overhead, Yardley believed the mission was unfolding per plan. His optimism soured over the next hour, though, as fewer than 100 of his 638 men reached the assembly point.

Scattered paratroopers continued to filter in, along with an Italian civilian, who warmly greeted the Americans. The man told Yardley several German trucks were parked nearby and offered to act as a guide. It was a tempting target; Yardley organized his men to attack on their way to the crossroads.

During the trek the Italian slipped away into the night. Not long after, Yardley’s lead troops engaged in a skirmish with a German sentry, whom they killed in a volley of rifle fire. As the column cautiously continued forward, German machine-gun bursts sent the paratroopers to ground. Tracer fire ripped through their ranks, killing several men where they lay. Yardley ordered the men to push through, using hand grenades to clear a path.

Suddenly, a German flare popped, casting an eerie glow over the battle and illuminating several tanks and armored vehicles—not the soft target the Americans were expecting. The enemy fire continued to increase and soon became overwhelming. Yardley’s attack collapsed. The paratroopers scrambled to withdraw, with German fire chasing them the entire way. One trooper, sprinting for a tree line, saw Doc Alden calmly firing his rifle toward the German positions. Alden managed to escape the pandemonium, but many did not.

Once the American attack stalled, German troops pressed forward across the killing ground, taking prisoners and searching the dead. One of them found Yardley, shot in his left hip, seeking cover in a roadside ditch. The German prodded Yardley with a bayonet before grabbing him by the collar and dragging him into their camp, where he received rudimentary first aid.

As the panzer captain questioned him, Yardley, unable to sit comfortably due to his wound, stared at his imitation coffee wondering where the mission had gone awry.

THE MOONLIGHT HAD DONE LITTLE to help orient the C-47 pilots. The pale light and deep shadows cast the terrain into a monochromatic maze; it was nearly impossible to differentiate one valley from another. After 45 minutes, many of the two-plane formations drifted apart.

Several pilots, realizing they were in the wrong valley, circled back to the coast to try another approach. Eleven misjudged the turn at Montecorvino and dropped their troopers 10 miles east of their intended location. Fifteen other C-47s managed to fly within five miles of the drop zone, but only four of them delivered their jumpers on target. The remaining transports were completely lost and scattered their paratroopers as far as 25 miles away. The pathfinder team’s navigation aids had been useless: the steep mountains thwarted transmitter reception and the Aldis lights required a pilot be virtually on top of them to be seen.

Compounding the navigation errors was the drop altitude. Surrounding peaks forced the paratroopers to jump from nearly 2,000 feet—more than twice the ideal altitude. Despite calm winds, the unavoidable drift from that height ensured that the troopers, whose chutes allowed only rudimentary steering, would float apart as they descended. Furthermore, almost all their equipment bundles—containing mortars, bazookas, ammunition, food, and radios—were lost or hopelessly snagged in trees.

Upon landing, the paratroopers groped through the darkness to gather whatever comrades and supplies they could. Their priority was to determine their location and how to get to the crossroads at Avellino. Little time had been available to study the terrain and few maps had been issued—and those were hard to read. Crawling under a poncho to scan a map with a flashlight or lighter revealed terrain contour lines webbed so close together that without knowing the name of a nearby village, it was impossible to determine one’s position.

ACROSS THE DARK VALLEY, the scattered paratroopers took stock of their situation. Knowing that they had to hold out for at least three days—awaiting General Clark’s infantry to push inland from the beaches—the clusters of men waged their own guerilla war, laying road mines, cutting telephone lines, sniping sentries, and ambushing small convoys.

Captain Casper E. “Pappy” Curtis and 17 other troopers slipped into the blacked-out town of Avellino and crept down its narrow streets. In the village square, they surprised and captured 10 Germans and commandeered their truck. They decided to drive the rest of the way to the crossroads with their haul of POWs, but an armored car interrupted them and the square erupted with gunfire. In the commotion, several POWs made a break for it. Hearing more incoming enemy vehicles, Curtis yelled for his paratroopers to disengage and scatter.

Southeast of Avellino, in the Santo Stefano del Sole valley, Lieutenant Dan A. DeLeo and his stick of jumpers were engaged in a fighting retreat. They had landed virtually on top of a German headquarters; two of the troopers drifted inside the compound, their parachutes entangled in the trees. Before they could free themselves, German soldiers riddled them with bullets. Behind volleys of fire and hand grenades, DeLeo and the survivors withdrew into the dark, carrying their wounded.

Elsewhere, Lieutenant Lloyd G. Wilson and Staff Sergeant George C. Fontanesi, uncertain of their location, led 10 men toward what they hoped was Avellino. Using a paved road as a guide, they navigated cross-country in the dark woods along the roadside. Suddenly, the lead scout tripped and fell onto a camouflage shelter tent, collapsing it as he crashed on top of its sleeping occupants.

“Schwinehund!”

The lost paratroopers had stumbled into the middle of a Wehrmacht bivouac site. Amid the confusion, the Americans ran forward—blundering into more tents. Before the startled enemy realized Americans were among them, the troopers scattered back into the woods, leaving the Germans bellowing at each other’s clumsiness.

Wilson’s group made it to the deserted crossroads just before dawn. With the sun rising, the troopers concealed themselves in a dry streambed. A few hours later, the Americans were alarmed when two elderly Italian women, picking greens, appeared to be heading directly for them. When it became clear the women would discover them, Wilson stepped out of the underbrush, pointed to the American flag on his shoulder, and whispered, “Americano… Americano.”

The women ran screaming back toward the road; the Americans scurried out of the streambed and climbed to a new vantage point. Soon after, the troopers watched a company of panzergrenadiers form a skirmish line and approach their former positions. When they were 40 yards away, the Germans opened fire with rifles and submachine guns before charging into the empty streambed.

The Americans waited until nightfall before heading for higher ground, where they found a cave. The men decided to hide there by day and go on the warpath at night, attacking targets of opportunity until their ammunition ran out. Staff Sergeant Fontanesi, who had been born in Italy, befriended a local farmer who provided the troopers with whatever food he could scrounge: bread and moldy bacon.

The scattered troopers sowed mayhem whenever they could. Still carrying their wounded, Lieutenant Dan DeLeo’s group ambushed a German motorcycle courier, stringing a telephone line across the road to “clothesline” the driver before pouncing on him with knives. Sergeant Solomon B. Weber, a radioman from New York, shot up a scout car, leaving two Germans dead in the middle of the road. Charlie Doyle and several of his comrades, who had been lounging on the beach less than 24 hours ago, raked the last troop truck in a convoy with their submachine guns as it snaked through the narrow streets of a village.

A few hours after the melee in the town square, 21-year-old Private Edward M. Pawloski and four of his comrades opted to cut through Avellino in broad daylight to reach the crossroads. As they entered the village, a burst of machine-gun fire tore into the group, killing Private J. J. O’Brien and Private Walter A. Cherry. Pawloski was struck in the hip and knocked off his feet. As he examined the wound, he was horrified to see smoke wafting out of his uniform—a bullet had hit the grenade in his pocket. He grabbed the explosive and hurled it at the enemy before running back toward the woods.

The group’s appearance from the north side of the village created panic among the Germans in Avellino, who thought the Americans had landed to the south. To them, it now seemed the paratroopers were everywhere; initial reports wildly exaggerated their numbers. General Heinrich von Vietinghoff, commander of the Wehrmacht’s Tenth Army, diverted troops and armored vehicles from the 16th Panzer Division to hunt the Americans.

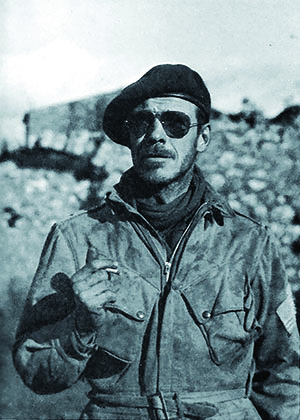

Most German patrols swept the valleys in vain, but some did stumble upon small bands of paratroopers who either fired a few rounds and ran or surrendered to the larger German forces. Doc Alden fell into both camps. After two days on the run, his luck ran out when a squad of Germans cornered the surgeon in a farmer’s field and captured him.

After his scout car ambush, Sergeant Weber bumped into a group of troopers led by the 509th’s executive officer, Major William R. Dudley. As far as Dudley could tell, they had landed off the map; although he had gathered nearly 60 men, he limited their actions to foraging patrols, opting to avoid the enemy until the Allied forces arrived from the beaches.

His decision did not sit well with most of the eager troopers, who believed it their duty to attack the enemy. The staccato of distant gunfire and the crump of grenades reverberating in the valleys were constant reminders that their comrades were out there taking the fight to the enemy. Some troopers decided to disobey the major and sneak away from the group to pursue their own war.

ONE OF DUDLEY’S FORAGING PATROLS met an Italian who told them of the nearby Montella Bridge, which German convoys regularly crossed. The troopers made another appeal to Major Dudley; he finally agreed to attack. In the six days since the drop, the men had recovered only 25 lbs. of demolitions from supply containers—not enough to topple the bridge, but enough to damage it.

That night, September 19, the men divided into several groups. First Lieutenant Justin T. McCarthy, leading the demolition team, recalled that they “waited for the moon to come up” but it was still so dark that several men held hands to keep together and avoid getting lost.

After positioning troopers on each end of the bridge for security, McCarthy and his team went to work, placing their explosives in the middle of the span and tamping them with bags filled with dirt. Without warning, several bursts of .30-caliber machine-gun fire startled those on the bridge; some of the paratroopers had fired on a German Kübelwagen motoring toward them. German soldiers spilled out of the vehicle and returned fire.

With the fuse set, the demolition team scrambled over the side. A minute later the charges exploded. Unaware of what was happening on the bridge, a convoy of four blacked-out German trucks came around the corner and drove straight into the melee. The lead vehicle’s front wheels slid into the crater, stalling the whole group. The paratroopers tore into them with machine guns and rifle grenades and withdrew up the steep slope of the mountain, leaving two of the vehicles in flames. “The worst part of that night’s job was the long hike uphill,” McCarthy remembered. “We were so dog-tired we just stopped and lay down where we were.”

Meanwhile, as the piecemeal units from the 509th created chaos in the mountains, the situation at the Salerno beachhead was improving. Supported by air raids and naval gunfire, General Clark’s forces repelled the final German counterattacks and pushed northwest toward Naples. By that time, ragtag groups of paratroopers were filtering back to friendly lines. Some opted to stay with advancing Allied units and continue the fight.

American infantry finally took Avellino on September 30, a full 16 days after the 509th dropped in. By early October, 520 of the 638 paratroopers had made it back to friendly lines. The remaining men were assumed to be killed, captured, or missing.

Nine days after German soldiers captured him, Doc Alden managed to escape and found his way to an American patrol. His battalion commander, Doyle Yardley, was not so lucky: he spent the rest of the war in Oflag 64, a POW camp in Poland.

TODAY THE 509TH’S CONTRIBUTION to the Salerno campaign remains largely overlooked. In his memoirs, General Matthew B. Ridgway, commander of the 82nd Airborne, wrote that the 509ers “caused the Germans vast annoyance, but whether they had any real effect on the Salerno operation is a matter for military historians to debate.” U.S. Air Force historian John C. Warren called the mission a failure, citing insufficient aircrew training, a difficult flight route, an obscure drop zone, inadequate pathfinder facilities, and loss of equipment.

For their part, the men of the 509th believed they had fulfilled the intent of their mission by sowing pandemonium behind enemy lines. By disrupting German communications and troop movements, the 509th undoubtedly kept units of the 16th Panzer Division on antiparachute patrols, preventing them from participating in counterattacks against the Allied beachhead. Measuring the effectiveness of that pandemonium is difficult, but the tenacity of the troopers and their willingness to close with the enemy at every opportunity reflected their aggressive spirit and fostered the growing reputation of the American parachute troops.

The battalion had more action ahead. In January 1944 it landed with U.S. Army Rangers further north at Anzio, acting as assault troops for the next Allied leap up the boot of Italy. A few months later, in August, the 509th conducted a combat jump into Southern France and fought through Belgium during the Battle of the Bulge. The battalion emerged from that campaign with only 7 officers and 48 enlisted troops—a total of 55—out of an original roster of 745 men.✯