Last time out, I made a plea to the readership: take the Red Army seriously. These guys were good. They weren’t just a mindless horde, and they didn’t just overrun their German adversary mindlessly. They were quite competently led, they planned their operations carefully, and they had a thoughtful war-fighting doctrine they called “deep battle.” They beat the Wehrmacht for a lot of reasons, and their superior size was only one of them.

But before any of you decide to climb on that Red Army love train, let me also issue a series of caveats. Compared to other armies of the period, the Soviets were an inflexible instrument. They rarely reacted well when the situation changed, and they seemed not to care at all about their own casualties. Even deep battle, which we might identify as their greatest strength, needs careful parsing. Deep battle—the insertion of second and third echelons along the same axis of attack as the initial assault troops—sounds like a good idea. It’s aggressive, it’s relentless, it nails an enemy to the wall and doesn’t let him maneuver, react, or recover. I’m not a general, but if I were, it’s exactly how I’d like to see myself.

Let’s be a little more critical, however. What if you were a commander in an army where “going deep” had become a guiding principle, a catchphrase, perhaps even an obsession? Let us imagine that you are a “Front” (army group) commander in the Red Army in mid-war. Let’s say that you have just landed a heavy offensive blow. Your shock groups have managed to grind their way through a well-defended German position. Your tank armies are currently motoring in the clear. The Fascist enemy is off balance. You know as well as anyone that the high command (read Stalin, the Vozhd, or “boss”) has high hopes for your offensive, and you don’t want to be the one to radio bad news back to the boss. That’s never a good idea.

Let’s be a little more critical, however. What if you were a commander in an army where “going deep” had become a guiding principle, a catchphrase, perhaps even an obsession? Let us imagine that you are a “Front” (army group) commander in the Red Army in mid-war. Let’s say that you have just landed a heavy offensive blow. Your shock groups have managed to grind their way through a well-defended German position. Your tank armies are currently motoring in the clear. The Fascist enemy is off balance. You know as well as anyone that the high command (read Stalin, the Vozhd, or “boss”) has high hopes for your offensive, and you don’t want to be the one to radio bad news back to the boss. That’s never a good idea.

A simple question : where would you stop? Just when do you send your message? Perhaps something along the lines of, “Troops exhausted. Mobile formations badly in need of rest and refit. Supply columns lagging. Forward troops halting.” Oh sure, it all makes perfect sense to us after the fact. Military historians are always to identify precisely when an offensive should stop.

But you’re not a military historian. You’re a Soviet Front commander. Sure, you’ve read the history and the military theory. As a Soviet commander, you are well schooled in it. The great theorist Clausewitz called it the “culmination point” (Kulminationspunkt), the moment at which all offensives wind down, lose their momentum, and need to be halted, lest they are vulnerable to an enemy counterstroke.

Then again, you’re not a history professor. You’re not Clausewitz. You are a high-ranking commander serving in an army with a ruthless institutional culture, an army that has a professed faith in something called deep battle. So you think very carefully about calling a halt to an offensive while you are still driving forward. After all, your decision might be “misunderstood” at higher echelons. Lack of will. Lack of faith. Lack of loyalty. And none of those are good in the 1940’s Soviet Union–especially lack of loyalty.

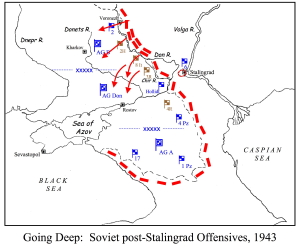

This was the precise situation facing some very good Soviet commanders in early 1943. They had all just landed what we might call a Big Hurt on the Wehrmacht. In November 1942, Operaton Uranus had slammed through the weak Romanian armies north and south of Stalingrad, linking up at Kalach on the Don and encircling the unfortunate German 6th Army. Most western histories trail off at this point, employing the simplistic notion of a “turning point” in the war and focusing on the plight of the encircled Germans until their surrender in early 1943.

Action aplenty continued on the front, however. The Soviets followed Uranus with one great offensive operation after another: Operation Little Saturn, crushing the Italian 8th Army; the “Ostrogozshk-Rossosh operation,” targeting the Hungarian 2nd Army; Operation Gallop against German forces on the Donets river and into the Donets basin (the Donbas) itself; and finally, Operation Star on the extreme right in the southern theater, smashing into German 2nd Army with great force. All across the front, Soviet mechanized forces were driving forward against minimal opposition. Opposition was sporadic. The sense of holding the initiative, that intoxicating feeling of success, was palpable.

Were the Germans finished? As a Soviet Front commander, you were actually asking yourself that question.

And then another one. Am I being overconfident? Is it time to stop?

More next time.

For the latest in military history from World War II‘s sister publications visit HistoryNet.com.