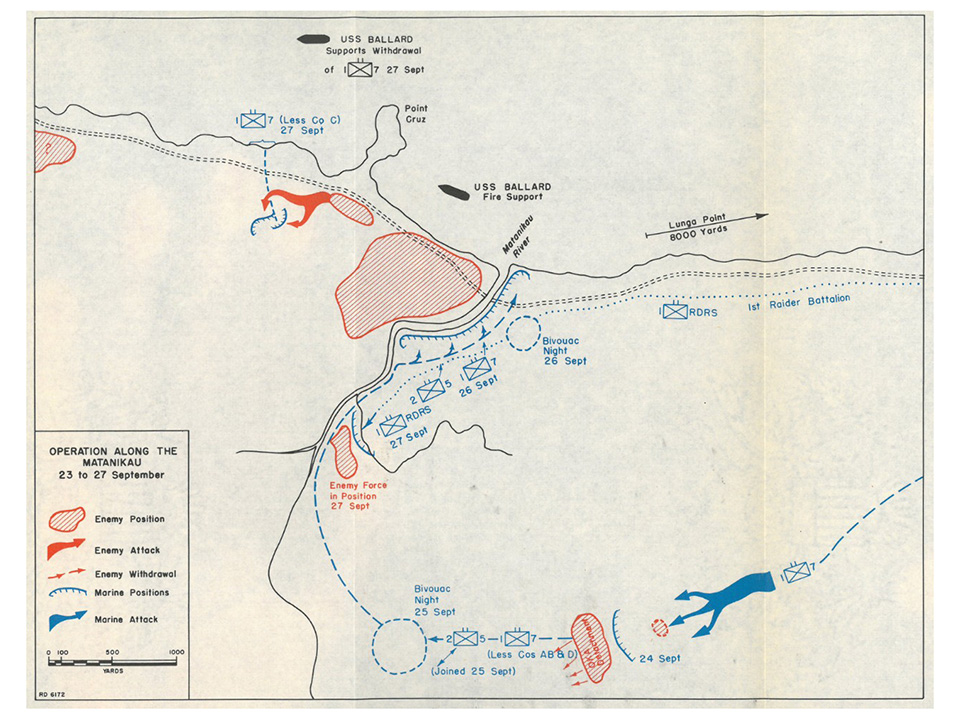

Over a month into the hellish fight for control of Guadalcanal, then-Marine Lt. Col. Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller ordered elements of his 1st Battalion, 7th Marines on an exploratory mission to the peninsula Point Cruz along the Matanikau River.

That region of the island was used as a staging area for Japanese forces to regroup and launch further attacks, particularly against the tenuously held Allied airfield dubbed Henderson Field.

Through miscommunication and miscues, that reconnaissance mission quickly turned deadly.

“On September 27, a message from the group was either misinterpreted or ambiguous, leading division headquarters to believe they had crossed the river and were fighting there… This resulted in the order for three companies of 1st Battalion, 7th Marines [to go ashore] via landing craft on a beach west of Point Cruz to enter the attack from the rear,” according to the National WWII Museum.

On that date Petty Officer in Charge Douglas Munro led the group of 24 Higgins boats, depositing nearly 500 Marines on the beachhead with the mission to wipe out the Japanese staging area.

Within an hour of landing, however, the Marines were in danger of being pushed back into the sea amid crushing Japanese bombing raids and gunfire.

The Higgins crews were still refueling when they received the message that the Marines needed to withdraw immediately. When asked by his commanding officer if the Coast Guard was able to go back and extract the overwhelmed Marines, the 22-year-old Munro reportedly gave a confident, “Hell, yeah!”

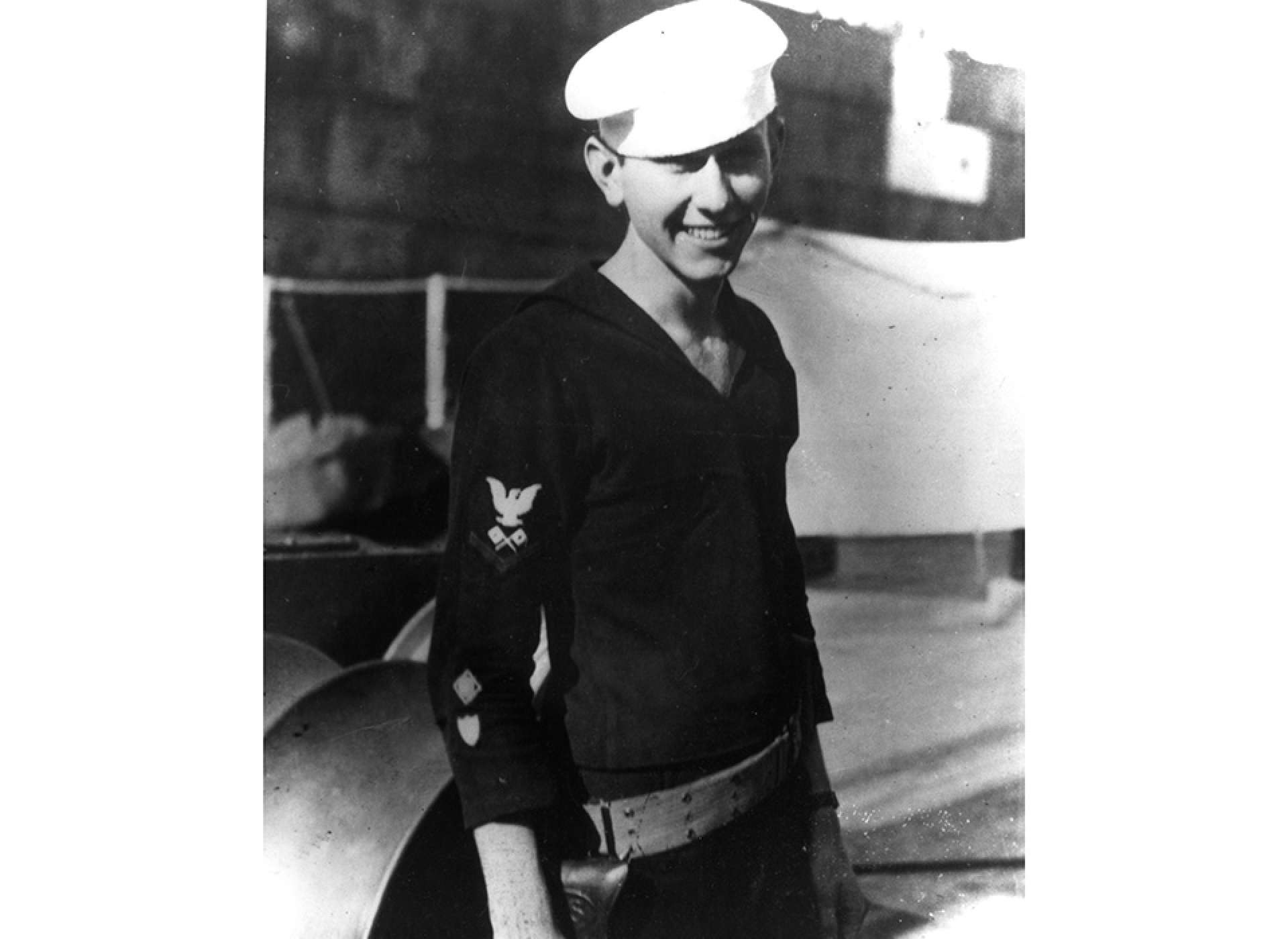

Born to an American father and British mother in October 1919, the then 19-year-old Munro enlisted with the U.S. Coast Guard in August of 1939 as war loomed and the likelihood of an impending draft all but certain.

But his journey from enlistment to combat in the Pacific was not linear.

“Coast Guard training in the latter part of 1939 was virtually nonexistent,” according to the museum. Sworn in on September 18, Munro and 18 other recruits “were sent to Air Station Port Angeles, where the staff there were clueless as to what was to be done with them. For three days they peeled potatoes, mowed grass, and helped with boat maintenance.”

After three days of menial labor, Munro was selected to be a crewman aboard the Coast Guard cutter USCGC Spencer, and the following year transferred to the transport ship USS Hunter Liggett to train as a coxswain for landing craft.

With the U.S. entry into the war, Munro was headed for the Pacific — and Guadalcanal.

After participating in several landings during the Guadalcanal campaign, on September 27 Munro did not hesitate.

“The Marines were being driven back to the beach and many did not have radios to request assistance,” according to the USO. “A single “HELP” spelled out in T-shirts on the ridge near the beach sent a loud and clear signal to those looking on.”

“Under constant strafing by enemy machine guns on the island, and at great risk of his life,” according to his Medal of Honor citation, Munro “daringly led five of his small craft toward the shore. As he closed in on the beach, he signaled the others to land, and then in order to draw the enemy’s fire and protect the heavily loaded boats, he valiantly placed his craft with its two small guns as a shield between the beachhead and the Japanese.”

As he used his landing craft to shield the beleaguered Marines from withering enemy fire, an enemy bullet struck the base of Munro’s skull. His best friend and fellow crewman Raymond J. Evans grabbed the wheel and continued Munro’s mission until the Marines were safely back at the Allied-held location of Lunga Point.

It was there that Munro briefly regained consciousness and asked his final question: “Did they get off?”

Evans replied that they had, with Munro reportedly dying with a smile on his lips.

Munro was posthumously awarded the nation’s highest military honor in May 1943, with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt presenting the Medal of Honor to Munro’s parents, James and Edith.