Racial discrimination, police brutality, and a society slow, and in some cases, unwilling to address widespread social injustice is a recurring theme in America. Over 100 years ago, the senseless death of a young black man, out for a swim on a hot summer day, plunged Chicago into weeks of violence and tragedy.

“The relation of whites and Negroes in the United States,” wrote the authors of “The Negro in Chicago,” “is our most grave and perplexing domestic problem.” The three-year study by the Chicago Commission on Race Relations, published in 1922, was the culmination of a landmark evaluation of the race riot that tore through the city in the summer of 1919.

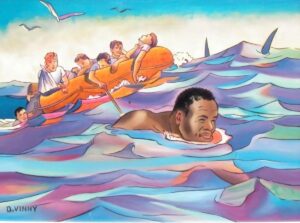

In July of that year, thousands of Chicagoans, amid the throes of a heatwave, thronged along the beaches of Lake Michigan. 29th Street beach was designated for whites and the 25th Street beach for blacks. This boundary even extended into the waters of Lake Michigan. On Sunday, July 27, Eugene Williams, a 17-year-old black youth, accidentally drifted into an area of water that was deemed to be for “whites only.”

One white beachgoer, indignant, began hurling rocks at Williams, causing the teen to drown. The pervading rumor was that Williams was struck in the head by one of the stones and drowned. Although in the autopsy, Williams’ body showed no bruises. The official coroner’s report cited that Williams drowned because the stone throwing kept him from coming to shore.

On the beach, “guilt was immediately placed upon a certain white man by several Negro witnesses who demanded that he be arrested by a white policeman who was on the spot,” the study wrote. “No arrest was made.”

Tensions on the beach escalated and a skirmish ensued when the officer arrested a black man instead. “The riot was under way,” the study noted. Williams’ death was the spark that touched off nearly a week of active, violent protests. But it was just the spark. Deeply rooted factors and injustices within the city kindled the flame.

From 1910 to 1920 the black population in Chicago rose from 44,103 to 109,504—an increase of 148 percent, as thousands moved north for better-paying jobs and to escape Southern racism and violence. At the same time, there was a 21 percent swell in the white population, largely made up of European immigrants.

With America’s entrance into World War I, industrial jobs were granted to blacks due to a labor shortage. Employment in manufacturing sharply increased during the war years and remained high after its conclusion. This created escalating labor tensions between blacks and veterans returning home from Europe, as well as immigrants in search of employment. The post-war cuts to the job market created a labor surplus that contributed directly to growing racial and economic friction throughout Chicago.

In his article “Why the Negro Appeals to Violence,” African American historian and social activist Willis Nathaniel Huggins wrote that “the large employers of labor who lured my people to the North with high wages and the city of Chicago itself have been derelict in providing housing accommodations for them.” It was impossible to place “80,000 people where 50,000 lived,” he wrote.

Chicago was not strictly segregated, but black renters and homeowners were increasingly restricted to what became known as the “Black Belt,” a narrow band of neighborhoods in South Side Chicago. According to “The Negro in Chicago,” 90 percent of Chicago’s black population lived in the Black Belt in the area between 12th and 39th, and Wentworth Avenue and Lake Michigan.

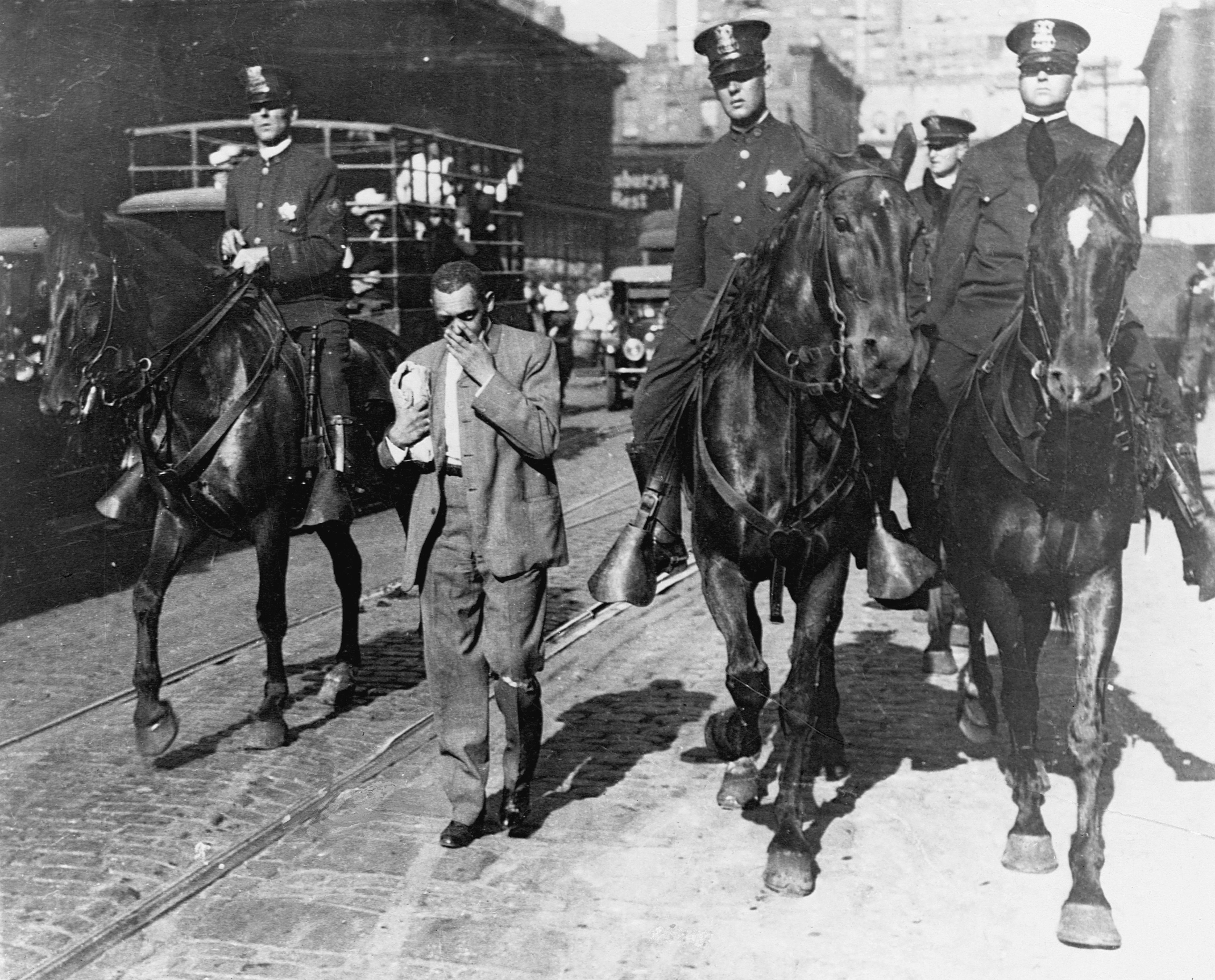

And it was there that 2,800 officers out of Chicago’s 3,500 deployed to respond to protests over Williams’ death, cordoning off the Black Belt. In the first few hours of the riot, 27 black men were beaten, seven stabbed, and four were shot.

Due to the cordon, only two police officers were assigned to cover the entire downtown area of Chicago. Subsequently, the following day, white men dragged many black men from street cars, savagely beating them. Four black men were killed and 30 severely injured. One white assailant was killed.

In the Black Belt, despite the heavy police presence, the rioting grew with escalating violence, looting, bombings, and arson. The police officers had formed a semi-permeable line, and in some cases, shielded white gangs who were emboldened by the generalized terror to “establish a racial quarantine of sorts, using sudden, brutal mob action to lay down a border between white and black Chicago,” wrote Adam Green, a professor of history at the University of Chicago, in the New York Times.

“On Halsted Street,” “The Negro in Chicago” study wrote, “crowds of young men rode in trucks shouting they were out to ‘get the n*ggers.’ ”

Other white assailants sped in cars through black neighborhoods, popping off rifle and revolver shots. With temperatures peaking at 96 degrees that Sunday, many black residents attempted to keep cool by sitting out on stoops and porches and unwittingly exposed themselves to gunfire.

In response, many black residents opened fire on any and all motor vehicles entering their neighborhoods, the study noted.

In many instances, when officers responded to attacks on blacks and their properties, they failed to collect sufficient evidence, ensuring that only few white assailants were apprehended or prosecuted, noted Green. Only 47 were indicted, and while two-thirds of the 537 injured were black, the indictment rates were double that of white rioters.

On Monday July 28, with the Chicago police unable to quell the riot, Governor Frank Lowden ordered the state militia to mobilize. By late Wednesday they had entered the city, and after 13 days, one of the nation’s bloodiest race riots came to an end—the toll was ghastly. Twenty-three blacks and 15 whites were killed, with 537 people injured.

“As the riot demonstrated, personal prejudice among patrolmen had always been a problem, even though the city employed a surprising number of black officers,” wrote Green. “The existence of prejudice among individual police did not necessarily mean that Chicago’s police department was, institutionally speaking, racist. But that would steadily change. Measures intended to modernize the police force—car patrols, information technology as a tool for deploying resources—ended up focusing enforcement on black residential areas.”

City and state officials, at the behest of many citizens and civic organizations, funded a commission to investigate the riot, its causes, and relations between whites and blacks in order to avoid such lawlessness in the future.

“These riots were the work of the worst element of both races,” Lowden said in announcing the commission. “They did not represent the great overwhelming majority of either race. The two are here and will remain here. The great majority of each realizes the necessity of their living upon terms of cordial good will and respect, each for the other. That condition must be brought about.”

The Commission on Race Relations consisted of 12 members—six black men and six white. Three years later, in a detailed, 828-page investigation, the commission bluntly stated in its report:

The “Negro problem,” was not the making of black men and women. “No group in our population is less responsible for its existence. But every group is responsible for its continuance; and every citizen, regardless of color or racial origin, is in honor and conscience bound to seek and forward its solution.”