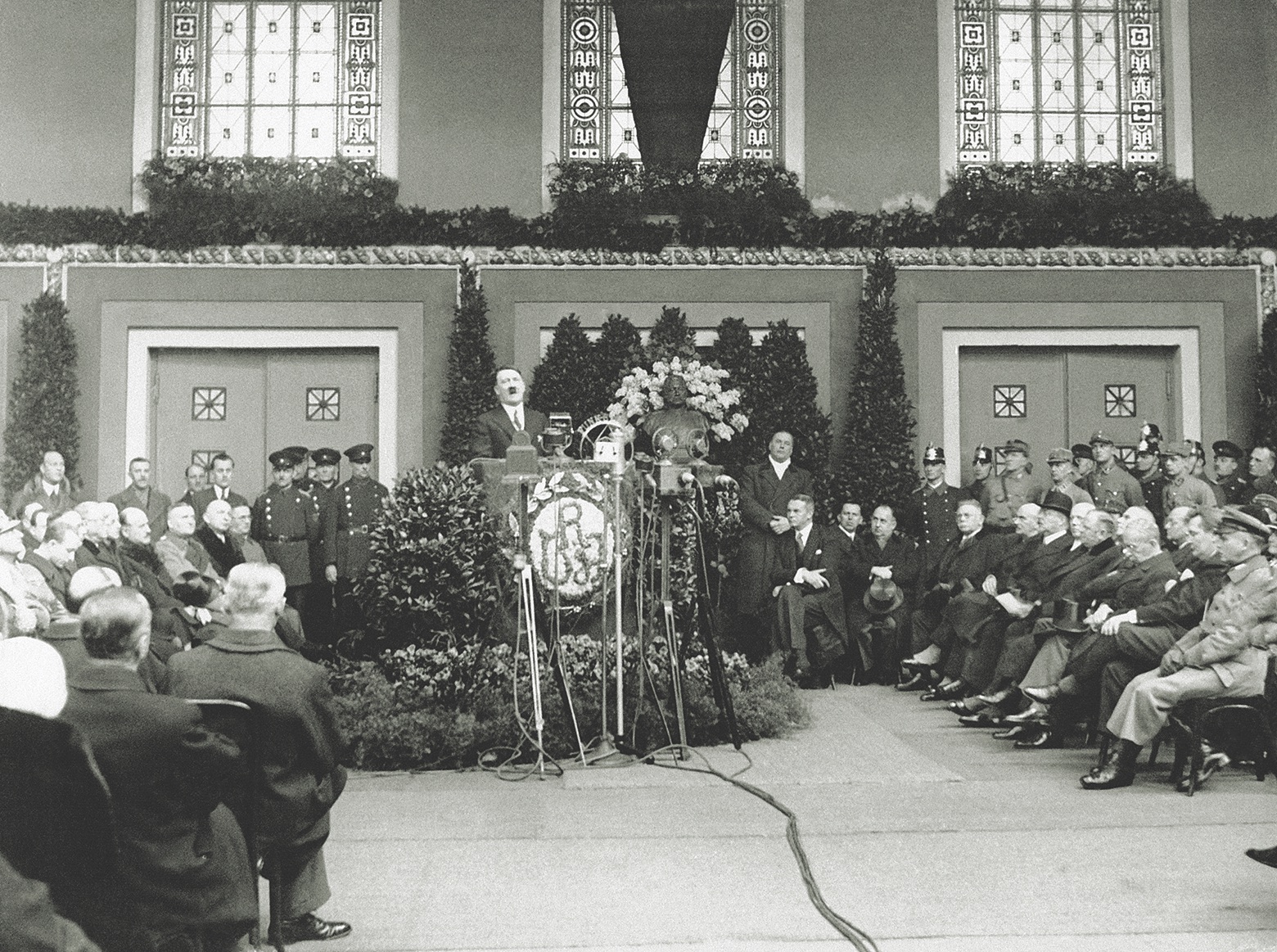

On February 11, 1933, Adolf Hitler strode into Berlin’s vast “Hall of Honor” to open the city’s International Motor Show. As he stood on a high, well-lit podium, dressed in a black suit, silence fell over the crowd inside.

Hitler had become Germany’s chancellor only 12 days earlier. The Nazi Party had celebrated with a nighttime parade through the capital that André François-Poncet, the French ambassador, described as follows: “In massive columns, they emerged from the depths of the Tiergarten and passed under the triumphal arch of the Brandenburg Gate. The torches they brandished formed a river of fire.” The jackbooted brownshirts marched past the French embassy and then down Wilhelmstrasse, raising their voices as they passed by the winged palace of the Reichspräsident.

Hitler moved swiftly to secure his rule. He called for new Reichstag elections, purged state offices of political opponents, arrested thousands, green-lighted attacks on Jews, commandeered radio stations, and recruited business leaders to bankroll his campaign. Feeding off the drummed-up fear of communist violence, he prepared to suspend a host of liberties guaranteed under the Weimar Constitution, including freedom of the press, the right to assemble, and protections against warrantless searches and seizures.

Amid this flurry of activity, he decided to use one of his first major public speeches as chancellor to promote the German automobile industry.

His voice quivering with a passion amplified by loudspeakers, Hitler declared his intention to slash taxes and regulations on Germany’s automotive industry, to align its growth and development with aviation, to build a nationwide highway system, and to dominate international motorsport. The captains of the industry, including Wilhelm Kissel, the chairman of Daimler-Benz, hung on his every word. “These momentous tasks are also part of the program for the reconstruction of the German economy!” the new chancellor exclaimed. With these rousing words, Hitler declared the motor show open.

Closely accompanying Hitler around the exhibition halls afterward was Korpsführer Adolf Hühnlein. A battalion commander in World War I, he had abandoned the army to join the Nazi Party in 1920 after hearing Hitler speak of Germany “never bending, never capitulating.” After the Beer Hall Putsch, Hitler’s failed attempt in 1923 to overthrow the German government, Hühnlein and Hitler had spent six months together in Landsberg prison, and they had remained close ever since. Hühnlein, who came across as grim and purposeful, was short, with heavy jowls and a high tuft of blondish brown hair swept back from his balding round head. Hitler had tapped Hühnlein, known to be a roughneck “man of action” rather than an intellectual, to command the National Socialist Motor Corps (the Nationalsozialistisches Kraftfahrkorps, or NSKK).

Although Hitler hadn’t spelled out his plans at the Berlin Motor Show, he saw revitalizing the automobile industry not only as key to delivering on his promise of a restored Germany but also as a factor in strengthening the Reich for future war. The purpose of the NSKK, a paramilitary arm of the Nazi Party, was to train a legion of men in driving and motoring skills, establishing the foundation of a mechanized army. For now, as Hühnlein often stated to the press, it was merely part of the “defensive force of the nation.”

Kissel knew differently, but Daimler-Benz supported Hitler’s ambitions, particularly as they brightened its prospects for sales. Over the past decade, the closer Hitler had come to power, the closer Daimler-Benz had drawn itself to him. Jakob Werlin, the head of the company’s dealership in Munich, had long fostered a friendship with the Nazi leader. Before the failed putsch in 1923, Werlin had sold Hitler his first Mercedes—a symbol, as historian Eberhard Reuss put it, of “force, strength, power, and superiority.” Werlin continued to provide discounted vehicles for Hitler’s cross-country political campaigns and became a self-declared confidant of the Fascist leader. Daimler-Benz also curried favor with Hitler by raising funds for the Nazi Party, advertising in Nazi newspapers, and sending its top Grand Prix drivers to visit him and share the glow of their fame with him.

Now that Hitler had become chancellor, Daimler-Benz’s executives needed him far more than he needed them. With the Depression causing car and truck sales to plummet by half from their record high in 1928, Kissel saw government support as the best path out of the crisis. Moves by the Nazis to crush the trade unions would help Daimler-Benz’s bottom line. More critically, orders for heavy trucks were rising, and it seemed clear now that Hitler intended to reinvigorate the German military in direct contravention of the Versailles Treaty. Prototypes for airplane engines and tanks had already been ordered. A move toward full-scale production would be a huge boon to Daimler-Benz, filling the excess capacity at many of its plants and boosting its profits.

A return to auto racing would be a crucial next step: Wins on the international stage would provide a marketing bonanza for Daimler-Benz’s cars, both at home and abroad. Further, success in racing would strengthen the company’s favor with Hitler and his minions.

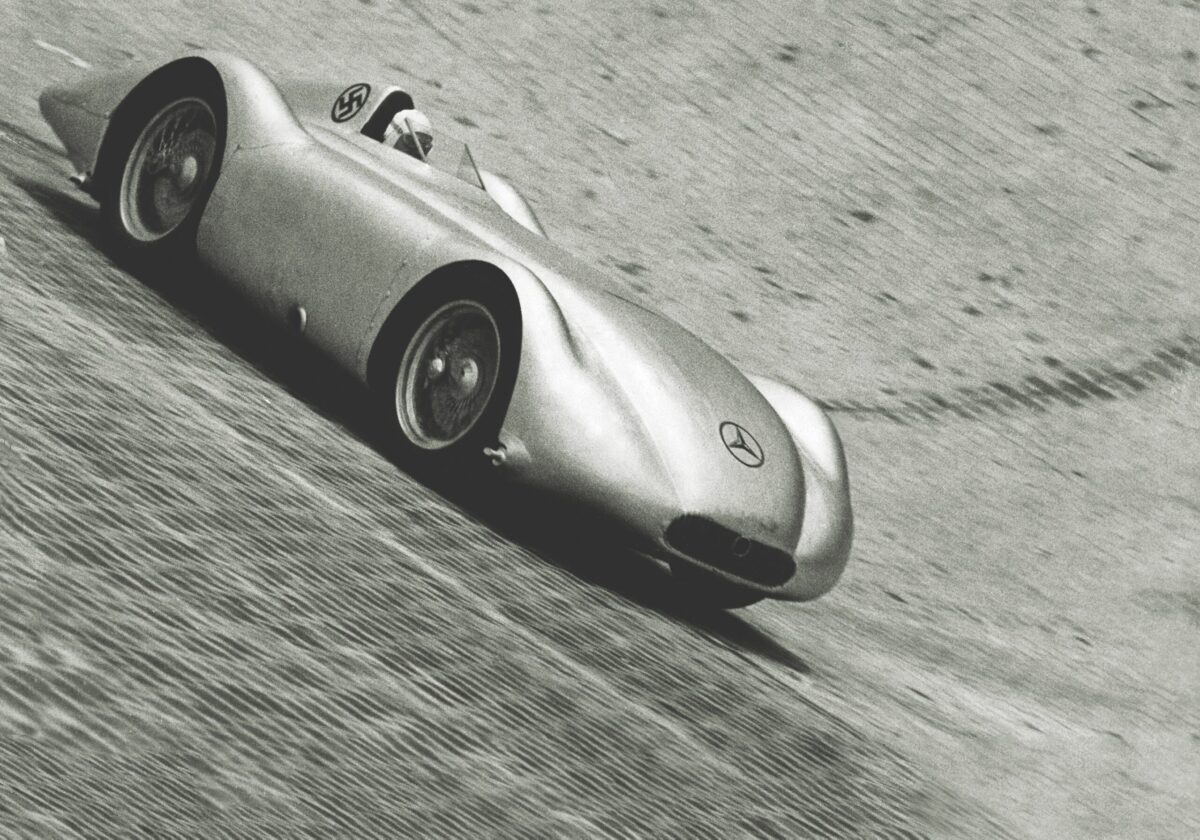

Working quickly, Daimler-Benz and rival Auto Union (the result of a merger of four Depression-hobbled German automobile manufacturers: Horch, Audi, DKW, and Wanderer) each designed race cars for the new Grand Prix formula season of 1934. Generously supported by funds from the Nazi state, the two automakers produced the fastest, most advanced cars ever introduced in motorsport up to that time. With their burnished aluminum bodies, the Mercedes and Auto Union race cars were nicknamed the “Silver Arrows.”

Over the next four years, the two companies absolutely monopolized the Grand Prix, fulfilling one of the promises Hitler made at the 1933 motor show. Neither French nor Italian automakers managed to design anything that could keep up with these supercharged bullets on wheels. In Germany, hundreds of thousands of fans came out to witness the new breed of race cars that their führer had spawned. The events had all the pageantry of the Nuremberg rallies. Lines of swastika flags flew above the grandstands. Nazi soldiers paraded to the clang of brass bands, and Stukas flew over the circuits. Korpsführer Hühnlein, “Supreme Chief of Nazi Motorsport,” was always there in his medal-studded uniform.

Hühnlein supervised every aspect of the Third Reich’s Grand Prix ambitions. Before the start of each season, he sat down with both Daimler-Benz and Auto Union and charted their race schedules to maximize German victories. To remain in his favor, they bowed to his demands on everything from what races to run to how much affection their drivers could show their wives or girlfriends at trackside to promoting the NSKK as “the cavalry of the future” at motor shows and political events. Their drivers’ celebrity was the perfect propaganda and recruitment tool. In return, the Nazi government continued to pour money into the two automakers’ coffers.

Josef Goebbels, Germany’s minister of propaganda, took every opportunity to herald the country’s dominance of the Grand Prix. “Racing is and always will be the highest embodiment of motorsport,” he declared at the end of the first season, “and thus the highest achievement of the nation in any international competition.” Not to be outdone, industry leaders stressed the importance of their work. The head of the national automobile club stated that the prowess of the Silver Arrows was “the benchmark for the industrial ability of a whole people.” An Auto Union executive was also unequivocal, describing the engineers and workers who built its race cars as “a community of prodigious men of German blood and soil who with tenacious will, a fierce heart, and boundless energy, labor for the kingdom of Hitler, marching proudly at its head.”

When the Silver Arrows swept the 1937 Vanderbilt Cup on Long Island, New York, Goebbels’s publicity machine churned out a stack of press releases. The “swastika flag hung on the victory mast at the raceway for over four hours,” one said; the American drivers were “motor-cowboys” while the Germans were considered “gentlemen” who showed “impeccable order and discipline that left a lasting impression,” said another; and the Silver Arrows showed undeniably that “German technology” was superior to anything in the “New World,” said yet another. Lead drivers like Rudolf Caracciola and Bernd Rosemeyer were heralded as “frontline” soldiers in the “racetrack battle.”

Their victories spurred the growth of the NSKK in its “battle for the motorization of Germany.” In swift order Hühnlein took over the national automobile clubs, started scores of driving schools, and recruited hundreds of thousands of new NSKK members.

For Daimler-Benz and other manufacturers, these prewar days were bright indeed. Production figures were growing by double digits every year, exports were rising, and profits were fat. The national Autobahn project was also making huge strides. Hundreds of thousands of workers, fleets of trucks and machinery, tons of iron and steel, and enough concrete to fill 100,000 railroad cars—all went into creating 4,287 miles of “Hitler’s Highways.” The führer was also moving forward with his dream of putting every German family in its own automobile, the Volkswagen (the People’s Car), a project spearheaded by Ferdinand Porsche.

In particular, the symbiotic relationship between the Nazi government and Daimler-Benz was scaled larger when it came to the rearmament of the military. Before Hitler openly defied the terms of the Versailles Treaty, he was already steering the entire German economy toward providing him with the tools of war. Daimler-Benz rapidly increased production of military trucks, armored vehicles, aircraft frames, and tanks. More plants were brought online, and Daimler-Benz engineers shared advances in technology they had made in producing their Grand Prix cars. A boost in engine power or a lesson in aerodynamics in a Silver Arrow design could be used equally well in a fighter plane.

When Hitler finally carried the world into war, his support of Germany’s automotive industry and its efforts in motorsport paid off in spades. Daimler-Benz was a leading armament producer for the Reich. It cranked out airplane engines, tanks, heavy trucks, armored vehicles, and all the spare parts the Reich demanded. It built massive plants in Germany and appropriated factories in Nazi-occupied countries. Daimler-Benz’s executives in Stuttgart, needing workers by the tens of thousands for these factories, did not hesitate to force occupied populations, prisoners of war, and concentration-camp inmates into forced labor under draconian conditions. All the while, profits soared.

Of course, the German army required drivers and mechanics. Thanks to the flood of recruitment during the heyday of the Silver Arrows, the NSKK provided a force of 187,000 trained drivers. Although many joked that NSKK stood for Nur Säufer, keine Kämpfer (Only Drunkards, Not Fighters), the organization was very effective in providing manpower for the Wehrmacht’s motorized infantry divisions. For this reason Hitler awarded Hühnlein, on his death from natural causes in 1942, the German Order, the Third Reich’s highest honor.

The NSKK also proved essential in building the fortified Siegfried Line of defenses, operating transport brigades, and executing blitzkrieg operations across Europe. Its motorcycle troops were the self-declared “spearhead of the modern war.” NSKK members also played an active role in the persecution of the Jews, starting with erecting roadblocks and bringing in stormtroopers during Kristallnacht. It was NSKK trucks that carried out the deportations and the ghettoization of vast numbers of Polish Jews. Throughout the Holocaust, the NSKK perpetrated numerous atrocities, including the shooting of Jews, especially in Russia and the Ukraine.

Such was the venomous end of Hitler boosterism that began at Berlin’s International Motor Show in 1933

Neal Bascomb is the author of 10 books, including The Winter Fortress: The Epic Mission to Sabotage Hitler’s Atomic Bomb. His most recent book is Faster: How a Jewish Driver, an American Heiress, and a Legendary Car Beat Hitler’s Best (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020), from which this article is adapted.

This article appears in the Summer 2020 issue (Vol. 32, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Behind the Lines |‘The Cavalry of the future’