In May 1969, U.S. soldiers paid a heavy price in America’s last great combat assault of the war. Was it worth it?

The 3rd Battalion of the 187th Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, came onto Dong Ap Bia, a mountain in northern South Vietnam, the morning of May 10, 1969. Most of the men were veterans of other assaults and this one, in the A Shau Valley near the Laotian border, seemed no different at first—except for its scale. John Snyder of Bravo Company recalled that this was “the biggest movement of troops I had ever experienced and the most helicopters I’d ever seen in one spot….you knew something big was happening but you didn’t know exactly what you were getting into—other than we already knew the A Shau was bad.” That suggested the approaching battle was not likely to be a “normal” engagement.

At least this was not a hot landing—no enemy fire met the Americans jumping off the helicopters. But that did not mean there was no enemy presence, as combat veterans well knew. As the men set up camp for the night, one officer looked at the forested hill above them and said, “I think we’re heading towards some pretty big shit.”

On the morning of May 11 the 187th Infantry prepared to move to the top of Dong Ap Bia, designated Hill 937 on military maps, about 3,000 feet above sea level. Bravo Company was assigned the lead, and company commander Capt. Charles Littnan told the men: “Go up that hill there and see what you can find, and then after that there’s a ridge that seems to lead in the direction we want. If all goes right, we should be on top of Dong Ap Bia by 1400,” or 2 p.m.

Littnan knew from experience that in Vietnam things did not always “go right.” They would be on the top by 1400 hours—but 1400 hours, 10 days later. By then Dong Ap Bia had become a slaughterhouse better known to Americans as Hamburger Hill.

The assault on Don Ap Bia was a major part of Operation Apache Snow, conducted by the 101st Airborne, under the command of Maj. Gen. Melvin Zais, to break the North Vietnamese Army’s control in the A Shau Valley. The valley, especially the western Laotian side of it, served as a major logistics center—a “warehouse” some Americans called it—for NVA forces. Tunnels and underground facilities harbored enemy units that could quickly infiltrate the surrounding areas and engage in attacks on coastal regions, as they had dramatically done during the 1968 Tet Offensive.

Joining the 3rd Battalion, 187th Infantry, in the operation were the 101st Airborne’s 2nd Battalion, 501st Infantry Regiment and the 1st and 2nd battalions, 506th Infantry Regiment. These units, along with two battalions of the 3rd Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, or ARVN, were ordered to assault different locations between the A Shau Valley and Laos, then converge at or near Dong Ap Bia. Meanwhile, the 9th Marine Regiment, 3rd Marine Division, would block the northern end of the valley.

Ever since the November 1965 battle in the Ia Drang Valley—the war’s first big battle pitting U.S. and NVA forces against each other—the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong had recognized the danger of sustained, conventional engagements with the Americans. U.S. firepower, including artillery and air, was too overwhelming, so communist units engaged in close-range firefights to negate or complicate the Americans’ ability to use their most powerful weapons. Communist forces usually resorted to surprise attacks, ambushes of small American patrols and units. They then withdrew before heavy firepower was directed on them. When Americans attacked, the North Vietnamese would defend their position for a short time, then pull back.

The experience at Dong Ap Bia would not follow the usual pattern of combat in Vietnam. The North Vietnamese had decided this would be a good place to fight. Their supply sources and reinforcements were only about a mile away in Laos, and Ap Bia was honeycombed with tunnels and peppered with formidable bunkers. An Air Force intelligence report had even predicted that for the North Vietnamese Hill 937 “was a better place than most to defend.” However, it is clear that U.S. commanders did not have good intelligence about enemy numbers and fortifications on the mountain.

The 3rd Battalion, 187th Infantry’s commanding officer, Lt. Col. Weldon Honeycutt, recalled that no one in the high command knew what to expect, neither the division headquarters nor the organization that oversaw all U.S. operations in the country, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, or MACV. “They had no idea,” he said. “They were just like us, going in raw.”

According to 1st Lt. Frank Boccia, leader of 1st Platoon in the 3rd Battalion’s Bravo Company, “We just knew we were going into the A Shau and that we would be seeking out the enemy, wherever he was.” Another platoon leader agreed: “Somebody should have known what we were going into. For whatever reason, they didn’t.”

Col. J.B. Conmy, commander of 101st Airborne’s 3rd Brigade Combat Team, said later, “This is my third war, and I haven’t bumped into a fight like this since World War II in Europe. The enemy has stood up and fought and refused to retreat.”

On May 11, when the 3rd Battalion’s lead platoon, 4th Platoon, Bravo Company, moved out of the tree line and began to cross a meadow beneath the heavily wooded mountaintop, it faced heavy fire from well-fortified bunkers. The platoon struggled to inch forward and then withdrew—a pattern of engagement that continued throughout the battle.

Three days later Honeycutt maneuvered the 3rd Battalion’s Charlie Company around to the north for a flank assault. Its troops were decimated by machine gun fire and rocket-propelled grenades. The battalion sent Bravo Company to support Charlie. As Bravo platoon leader Boccia moved up to the ambush site, he saw bodies everywhere. “For that first mind-freezing moment it had seemed as if the ground were literally covered with them,” he said. Boccia discovered that many of the American bodies were wounded, not dead. The advancing units thus had to stop and get the casualties down to a clearing where medevac helicopters could pick them up. These evacuations were a continuing problem as the Americans pressed up the steep slope in the face of heavy machine gun, mortar and rocket fire from the bunkers above.

The 101st Airborne had run into the 29th NVA Regiment, a seasoned combat unit. The fighting was sustained and ferocious. The 2nd Battalion, 501st Infantry, and 1st Battalion, 506th Infantry, along with the ARVN 2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry, moved to support the 187th, but struggled to get up adjacent hills.

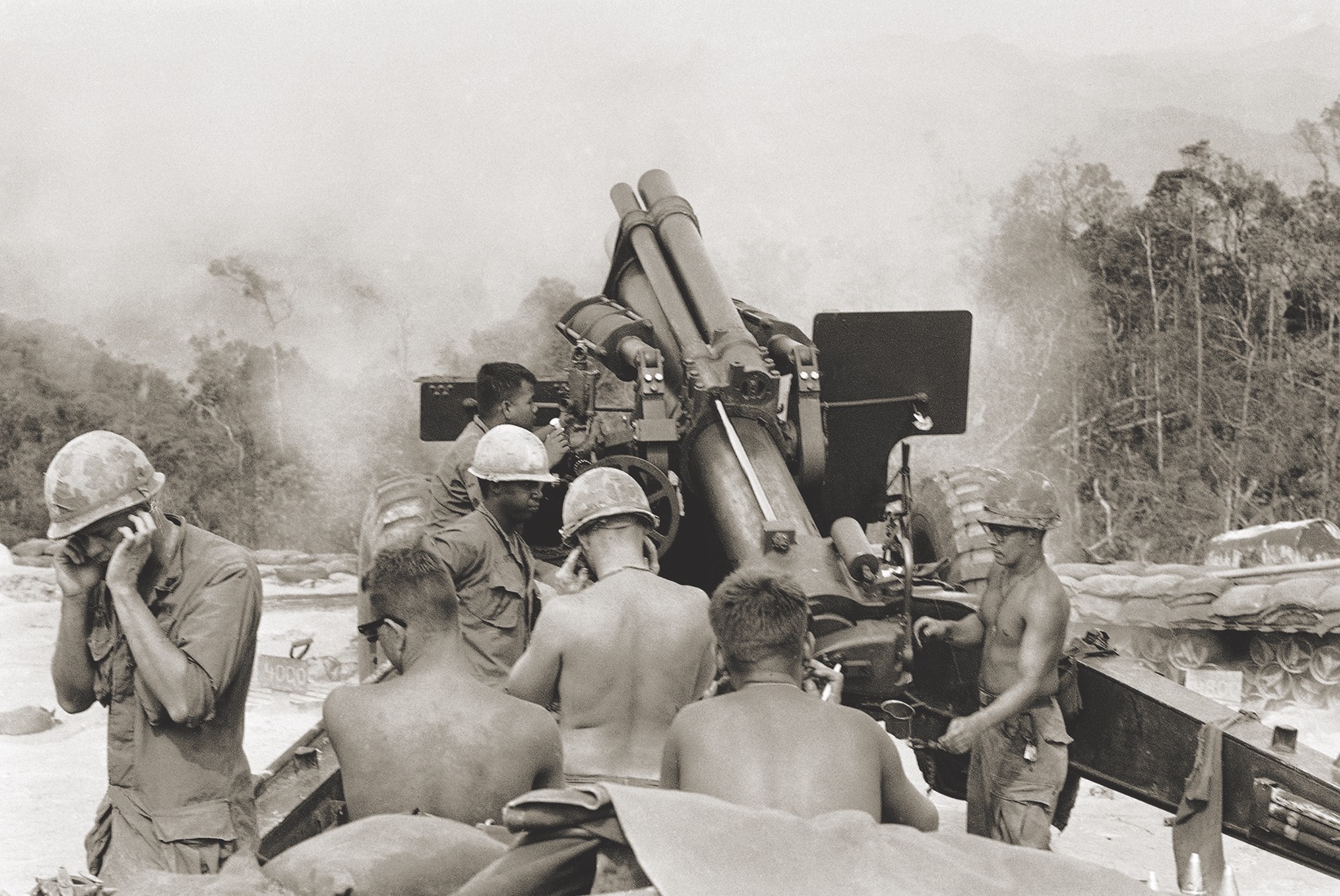

The 101st Airborne sustained heavy losses, including the 27 men killed on May 13 when North Vietnamese sappers assaulted Charlie Battery at Fire Base Airborne, an artillery base on Dong Ngai, a mountain just a few miles from Dong Ap Bia.

Critics later asked why the U.S. did not use B-52 bombers to destroy the enemy’s tunnels and bunkers. One reason was the intelligence failure that provided an inaccurate assessment of the defensive fortifications and the number of enemy troops, which became clear only after the 101st Airborne was on the hill in force. B-52 bombs could not be dropped with precision on a small specific target, a problem when friendly troops were nearby. American troops’ close proximity to the enemy also complicated the use of other air and artillery support.

Nonetheless, the U.S. still hit the hill with a massive amount of firepower: 1,088.5 tons of bombs, 142.5 tons of napalm and 31,000 rounds of 20 mm shells. Mac Campbell, a Marine F-4 Phantom II pilot who flew air support missions, recalls that American aircraft “just pounded that hill. I still visualize that hill. We cleared that place.” But even with careful strikes, Americans inevitably suffered “friendly fire” casualties.

Despite the 3rd Battalion’s significant losses, Honeycutt insisted the men were capable of making the final assault, planned for May 20. The colonel’s battalion, reinforced by Company A of the 2nd Battalion, 506th Infantry, once again headed for the top. They were supported by other battalions, which attacked from different sides of the mountain. This time Honeycutt’s men reached the summit and stepped onto a devastated moonscape of smoldering fires. The remaining NVA forces had slipped away into Laos.

Veterans of the battle vividly recalled the ferocity of the fighting and the courage of the men who repeatedly pushed through a torrent of enemy fire. They talked about the smell of death and the body parts ripped off by rocket-propelled grenades or land mines that sprayed metal fragments. “It’s just unimaginable,” one infantryman said. “Bullets were just trimming the bark off the trees and the leaves were falling down like it was fall.” A medic remembered, “It was just absolute confusion and mayhem.”

Another soldier put the days of battle in perspective: “We went up that day…we got ambushed. We withdrew. We went back up again that same day, probably just within 20 or 30 minutes—got hit again. Withdrew. Spent the night, went up there the next night to recover the dead bodies. The next afternoon, we started going up again around 1:30 in the afternoon. We got hit again. At this time, we’re going, ‘What the hell is going on?’”

Another said, “You’d go up, you’d battle, see people get killed, see people get wounded. After so many dead, we’d pull back and chow down and reorganize and take care of the wounded and evacuate them, and the next time, the exact same thing.”

After getting orders to go back up again, one platoon leader thought, “This is the way that the guys at D-Day must have felt.” He also recalled thinking, “Oh no, We can’t go back up there.” But he did. There were a few instances when men said they weren’t going back, and one officer recalled being “scared to death of mutiny.” But after men griped and vented their frustration, they always picked up their weapons and moved back up the mountain.

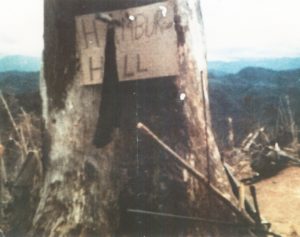

Dong Ap Bia was called “the mountain of the crouching beast” by the Montagnards, a group of tribes that had lived in the region since ancient times, and by the end of the battle some American soldiers felt that the beast had spit them out like the ground meat of a hamburger. John Wilhelm, a Time magazine correspondent, went to the top of Ap Bia after the fighting and spotted a 101st Airborne neckerchief, pinned to a tree with a piece of cardboard that had two handscrawled words: “Hamburger Hill.”

The tally of Americans killed in this battle is somewhat complicated because casualties from other parts of Operation Apache Snow may or may not have been included in the battle for Dong Ap Bia. But recent counts indicate 71 or 72, with some 400 wounded. The American body count of North Vietnamese dead is 630.

Only four of the 20 platoon leaders in the 187th Infantry who went to Ap Bia on May 10 made it to the top of the hill on May 20. The 16 others were dead or wounded. As their leaders fell, junior enlisted men assumed greater responsibility. “A lot of them had not been out of high school and in the Army for a year before they came to Vietnam,” noted one soldier. “And here they were taking over tactical operations in the jungle in Vietnam.”

Among the first men to reach the top of the hill on May 20 was 2nd Lt. Don Sullivan from Winthrop, Massachusetts. He was accompanied by just 18 of the 42 men originally in his 2nd Platoon, Charlie Company. Sullivan said that when they reached the top one of the men crawled over to him and said, “You know, sir, when you took over your platoon we all thought you looked about 15 years old. Now you look really old, and you’ll never look young again.”

After the battle, the survivors had an R&R break at Eagle Beach, on the South China Sea northeast of Hue. Sullivan remembered the showers, clean uniforms, plenty of hot food and cold beer. While there he received a letter from his mother, Helen, who wrote: “The News this week is all bad. They are constantly talking about the 3/187th taking horrible casualties attacking a hill. I certainly hope you had more sense than to go up there.”

The constant talking back home about Hamburger Hill was quite unusual for a specific battle in Vietnam. By 1969, the war itself was a subject of constant debate and criticism, but specific battles were largely unnoticed in the States. Unlike many past wars with large-scale engagements involving thousands of troops, combat in Vietnam was marked by intense and brief skirmishes, ambushes and small-unit actions. Those fights were over quickly and seldom had the drama for news coverage back home. By 1969, the Vietnam War had just a handful of sustained battles: Ia Drang in 1965, Dak To in 1967, Hue and Khe Sanh in 1968, and now Hamburger Hill.

Five days after the battle began, Walter Cronkite in his May 15 broadcast on the CBS Evening News made a brief, vague reference to it: “Tonight American paratroopers are battling for control of a key mountain in the area.”

In the following days the battle was mentioned in other news reports, including a detailed story on May 19 by Jay Sharbutt of The Associated Press. Sharbutt, attached to the 187th Infantry, quoted a soldier who said, “That damn Blackjack [the call sign for Honeycutt] won’t stop until he kills every damn one of us.” Another told the AP reporter: “I’ve lost a lot of buddies up there. Not many guys can take it much longer.”

By the next day the moniker “Hamburger Hill” had made it into news stories. A New York Times front-page headline read: “G.I.’s in 10th try, fail to rout foe on peak at Ashau.” Ironically, that was the day the 187th Infantry secured the hill. It was also the day Democratic Sen. Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts criticized the Nixon administration on the Senate floor for talking about peace while engaging in a “senseless and irresponsible” battle that sent “our young men to their deaths to capture hills and positions that have no relation to ending this conflict.” He insisted that “American boys are too valuable to be sacrificed for a false sense of military pride.”

Criticism of the war, although present virtually from the beginning, picked up significantly as the fighting continued with heavy casualties and no clear resolution in sight. In the 1968 election Richard Nixon promised that he had a secret plan to end the war, and public opinion polls indicated that most Americans wanted it to be over. Nonetheless Kennedy’s argument marked a new turn: He questioned the tactics and military decisions on the ground.

This led to a great debate about the battle, a debate that intensified in early June when Maj. Gen. John Wright, who had succeeded Zais as the 101st Airborne’s commander through a scheduled rotation, announced that the division was going to withdraw from the contested hill.

That departure made the purpose of the battle even more controversial, reflecting the military’s difficulty in explaining tactical operations to Congress and the American public. Zais had earlier pointed out that the operation had not been designed to seize and control ground. This was a war of attrition, and the goal was to kill enemy soldiers and disrupt their supply system.

There is no evidence that the U.S. military command ever intended to occupy Dong Ap Bia for the long term. Occupying ground near Laos without secure supply routes over land was not a good military option. “We didn’t retreat from that hill,” Zais said. “We left it because we had defeated the enemy.”

Some of the soldiers complained later about abandoning the hill. One said, “We felt like we owned that damned property and needed to keep it.” But most shared the view that this was the nature of war. As one said, “We went up a lot of hills and a lot of ridgelines and we didn’t keep ’em. You just went up, and if you had a fight, you had a fight, and then you went off.”

On the cardboard sign that bestowed the name Hamburger Hill, someone had written at the bottom: “Was it worth it?”

Neil Sheehan, who had served in the Army in Korea and was a distinguished correspondent in Vietnam, wondered if the men who fought and died there had questioned their purpose. “Perhaps there is no difference, but it ought to be one thing to perish on the beaches of Normandy or Iwo Jima in a great cause and another to fall in a rejected and unsung war,” he wrote in Harper’s Magazine.

Perhaps. But there is little evidence that most of those who were in combat gave much thought to whether they were fighting for a “great cause” or engaged in a war that many Americans rejected. They fought for the day, for their buddies, for their own sense of purpose, and for staying alive. Indeed, the men who fought at Normandy and Iwo Jima framed their encounter in a similar manner. As a weary Marine fighting at Korea’s Chosin Reservoir in 1950 said when asked by a correspondent what he most wanted: “Give me tomorrow.”

Another Vietnam War correspondent, Ward Just of the Washington Post, said it is not useful to wrestle with questions of whether a battle was “worth” the losses. “An army is fielded, and if it is a good army, it fights. If it must fight against an entrenched enemy on a hill, then that is what it does. The war does not take place in a classroom or on the pages of a newspaper, and it is not fought by…men who read headlines.”

One Hamburger Hill veteran said the battle was of a greater magnitude, but not much different from others in Vietnam. The men who survived moved on, “and then you were back in the jungle doing what you got the big bucks to do,” he said.

The Battle of Hamburger Hill was consequential, not just for those who fought there so valiantly, but also for the publicity and controversy it generated, which influenced the country’s war strategy.

Nixon, looking for time and a means to secure a “peace with honor,” indicated during the battle that the United States was not seeking a “military victory” in Vietnam—something that had always been the case, but now he made it explicit.

After an early June meeting at Midway Island with South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu, Nixon announced a plan dubbed “Vietnamization”—handing more of the fighting to South Vietnamese forces and beginning a drawdown of American troops starting that summer. The nature of tactical operations also began to shift that summer as the Pentagon informed MACV that it did not want any more extended engagements. There would be no more Hamburger Hills.

—James Wright is an American historian and former president of Dartmouth College. He has been recognized for his support of veterans by the secretary of the Army, the commandant of the Marine Corps and the commander of the Veterans of Foreign Wars. He is the author of Those Who Have Borne the Battle: A History of America’s Wars, and Those Who Fought Them (2012), and Enduring Vietnam: An American Generation and its War (2017). He interviewed 160 Vietnam veterans or family members for the Vietnam book, including 26 involved in the battle for Hamburger Hill.

This article was published in the June 2019 issue of Vietnam magazine.