In November 1936 two men from Canada drove through France’s Rhone Valley on their way to the Spanish Civil War. A handwritten sign on the side of their battered Ford station wagon made it clear that the Canadians, like the majority of foreign volunteers, were on the side of Spain’s recently elected Republican government.

French sympathizers raised clenched fists in support as the station wagon passed by. But one of the men, Norman Bethune, a physician from Montreal, barely noticed. He spent much of the journey immersed in a book about blood transfusions.

Four months before Bethune arrived in the capital city of Madrid, General Francisco Franco had declared war on the new government. Franco’s Nationalist forces had the support of wealthy landowners, big business, leaders of the Catholic Church, and the Falange, Spain’s Fascist party. Fascist leaders elsewhere in Europe also rushed to Franco’s aid: Germany’s Adolf Hitler provided 100 warplanes and 16,000 soldiers; Italy’s Benito Mussolini sent 50,000 troops. The Spanish government, on the other hand, was backed by workers, liberal writers, and artists and left-wing political parties, along with some 40,000 volunteers from more than 60 countries.

Ten Years of Action

From his earliest years, Bethune had thrived on taking chances. In 1896, when he was just six years old, he disappeared from his Toronto home one morning only to return hours later to announce that he had walked across the entire city (more than nine miles). His father, a Presbyterian minister, was not amused. Bethune loved being outdoors and tackling new challenges. He dropped out of university for a year to work at a logging camp in northern Ontario. After chopping down trees all day, he spent the evening teaching lumberjacks how to read and write. Later, his medical studies were interrupted by World War I. Serving as a stretcher-bearer at the Second Battle of Ypres in Belgium gave him firsthand knowledge of how quickly the wounded died from lack of blood.

After the war Bethune completed his medical studies and headed to London. He worked at the Hospital for Sick Children on Great Ormond Street and became fascinated by surgery. In 1923 he married a Scottish heiress, Frances Campbell Penney, whom he later divorced, remarried, and again divorced—all within 10 years.

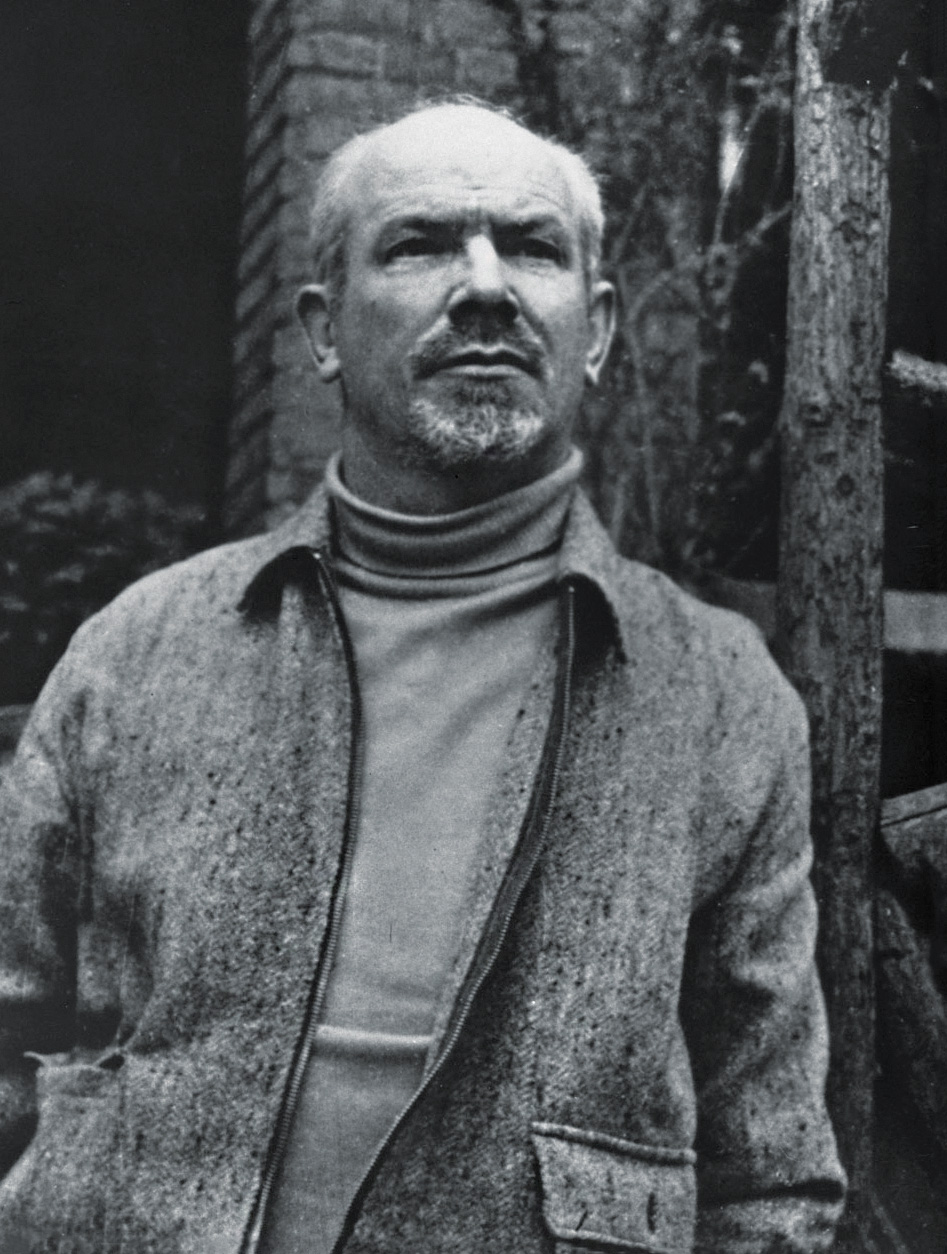

At this stage of his life, Bethune was a handsome man who enjoyed life to the full. Women loved him. One friend described the dashing doctor as “the most aggressively male creature I ever encountered.”

In 1926, after he’d returned to Canada, Bethune contracted tuberculosis and went to an expensive sanatorium in New York for treatment. He had fun there at first, sneaking out at night and drinking bootleg whiskey in a nearby town. But as months passed and his disease got worse, Bethune came to fear that he was dying. He thought of suicide and painted a mural that included his gravestone.

Fortunately, the sanatorium had a good library, and he came across an article in a medical journal that gave him hope. It described a procedure in which a needle was used to collapse a diseased lung to let it heal. Bethune rushed to his doctor, gave him detailed instructions about how to perform the procedure, and demanded to go straight to the operating room. The operation was so successful that when the surgeon checked on Bethune hours after collapsing his lung, he found him standing on a chair finishing his mural.

Bethune later wrote that his year in the sanatorium had given him time to think and deepened his intellectual and spiritual life. Being treated at one of the most expensive sanatoriums in North America had also awakened Bethune’s social conscience. “There are two kinds of tuberculosis—the rich man’s and the poor man’s,” he wrote. “The rich man lives and the poor man dies.”

“Something Great For Humanity”

Bethune told friends that he was determined to do something great for humanity before he died. Finding a cure for tuberculosis was at the top of his list. He took up thoracic surgery in Montreal, but condemned other surgeons’ old-fashioned ways, shouted at nurses, and complained about equipment.

One doctor remembered seeing a trail of surgical knives that Bethune had discarded along a hospital hallway because they weren’t sharp enough.

He was unpopular with his colleagues, but his perfectionism brought huge benefits to his profession.

He invented new surgical instruments that transformed cardiothoracic surgery, including the Bethune Rib Shears (with “long handles, powerful biting jaws, suitable for all ribs,” a catalog said)—that are still in use today.

Outside the hospital Bethune hung out with artists, painted, and wrote poems, plays, and short stories. Though a self-proclaimed socialist, he was a vain man and enjoyed life’s luxuries, splashing his face with the most expensive colognes and dressing elegantly. In 1935 he traveled to Russia, where he was hugely impressed by its free hospitals, and on his return he joined the Communist Party of Canada, a banned organization. He passionately campaigned for free health care, urging the Canadian government to adopt a national health system, but his plans were rejected.

So when the Spanish Civil War broke out, Bethune could hardly wait to leave Montreal and rush to the aid of his Spanish comrades. He looked on fascism as a disease, an insanity that threatened civilized society. “It is in Spain the real issues of our time are going to be fought out,” he wrote. “It is there that democracy will either die or survive.”

To The Front Lines In Spain

On reaching Madrid in November 1936, Bethune wrote to a friend: “The world war has started—democracy against fascism. I wouldn’t be anywhere else.” But Madrid was a city under siege. Franco’s troops surrounded most of the Spanish capital, and Bethune wrote that Fascist bombs fell like “great black pears leaving bodies where once there were women and children.”

The first blood transfusions in history took place in France in 1667, when King Louis XIV’s doctor gave animal blood to humans—with disastrous results. Transfusions then fell out of fashion until the 19th century, when the invention of rubber tubing allowed blood to be transferred from donor to recipient. In most cases, however, the donor had to lie on a bed next to the person who needed the blood.

Nearly as soon as he set up Servicio Canadiense de Transfusion de Sangre, Bethune began advancing the science of blood transfusion. Once blood was collected, he and his workers put it into a bottle and stored it in a refrigerator. Crucially, they added sodium citrate to the blood to stop it from clotting. When Bethune appealed for blood donors on radio and in newspapers, so many Republican patriots queued up that on some days it was not possible to take blood from everyone in line.

In February 1937 Bethune took his transfusion unit to the front lines. He and his mobile transfusion team covered a huge area with more than 100 hospitals and first-aid stations. As soon as a call for blood came, the refrigerator would be loaded, and Bethune and his driver would be off. He later spoke of seeing wounded soldiers lying white-faced and motionless in their hospital beds and described how he watched their skin turn pink and their eyes sparkle as the bottled blood brought them back to life.

It was dangerous work. He and his team were once forced to jump out of their truck when it came under fire from Franco’s soldiers. Another time, as Bethune was taking his mobile blood unit to southern Spain, he witnessed a scene that would haunt him for the rest of his life:

When the little sea port of Almeria was completely filled with refugees, we were heavily bombed by German and Italian Fascist airplanes….They deliberately dropped ten great bombs in the very centre of town on the exhausted refugees….After the planes had passed I picked up in my arms three dead children from the pavement….In the darkness the moans of wounded children, shrieks of agonized mothers, the curses of the men rose in a massed cry higher and higher to a pitch of intolerable intensity.

Deciding to Help Mao

After seven months Bethune had a falling out with Spanish authorities who wanted to take over his transfusion service. He decided to return to Canada, leaving behind a fully functioning mobile blood service. It has been estimated that the number of people who died from their wounds dropped by 30 percent thanks to Bethune’s pioneering work.

Bethune was on a cross-country tour of Canada, raising money for the Spanish Republican cause, when on July 7, 1937, Japan launched a full-scale attack on China. China was already in turmoil, with the Nationalists under General Chiang Kai-shek trying to destroy the Communist forces led by Mao Zedong.

As Bethune saw it, the Chinese were involved in the same struggle as the Republicans in Spain—a fight against fascism—only on a much greater scale. He resolved to help Mao. In January 1938 he left Vancouver on a ship headed for Hong Kong, accompanied by two other Canadians: Charles Parsons, an experienced doctor, and Jean Ewen, a nurse. Ewen was fluent in Chinese.

When they arrived in Hong Kong, however, it became apparent that Parsons, an alcoholic, had spent most of their expense money buying drinks on board the ship. There was nothing left to pay for hotel rooms.

Bethune hit the roof. “I have not seen such a temper before, except in my father,” Ewen wrote. “He stomped and kicked everything in sight except Parsons.”

Parsons was left behind as Bethune and Ewen made the dangerous journey by foot and train to join Mao’s Red Army. It took them six weeks to travel some 800 miles to Mao’s headquarters in Yan’an. Along the way Bethune treated wounded soldiers and civilians. Ewen helped him remove bullets from arms and legs, set broken bones, and amputate infected limbs.

Even in the midst of death and destruction, Ewen had it drummed into her how Bethune expected her to behave: “I was never to call him by his first name. I was not to take it upon myself to diagnose or treat patients. I was a servant, no more, no less.”

Caring for Mao’s Soldiers

Ewen found Bethune to be unsympathetic and rude but was impressed at how calmly he accepted the dangers they encountered on their journey. They were bombed, shot at, and several times nearly killed.

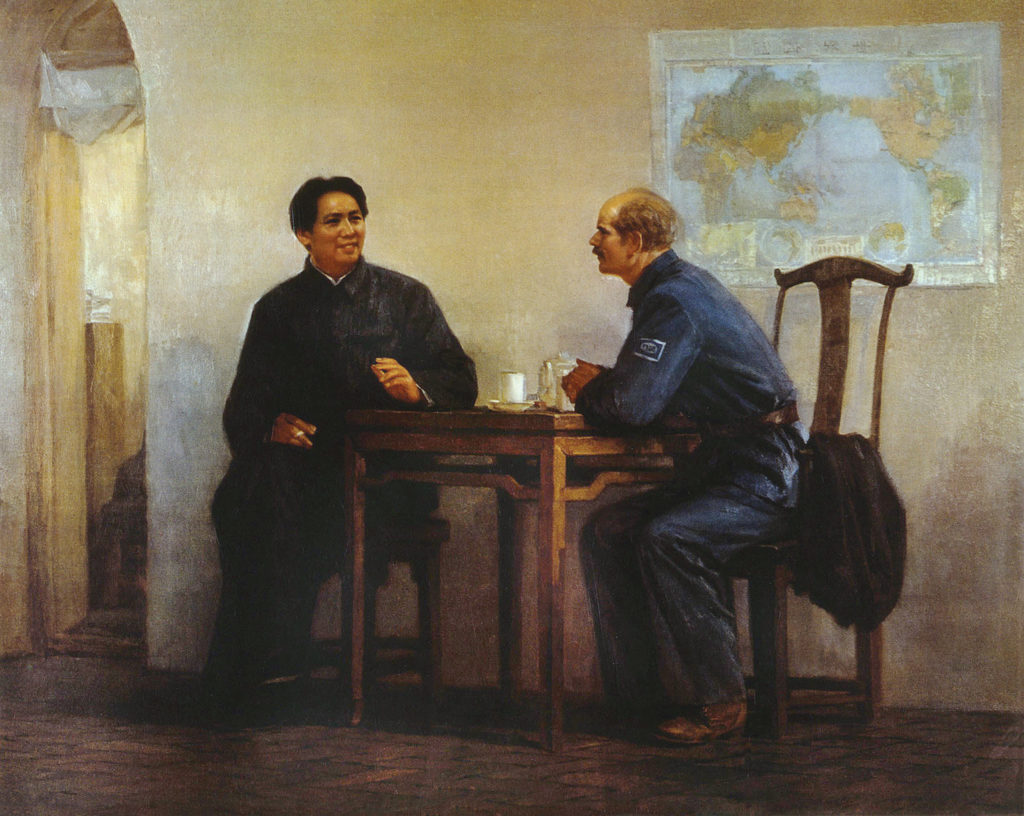

When they finally arrived in Yan’an, the town’s citizens waved flags and banged drums, as Bethune’s reputation had reached even this out-of-the-way place. No sooner had he and Ewen collapsed in their beds than a knock at the door summoned them to meet Mao. Their escort explained that Mao worked from midnight until eight or nine in the morning because that was when it was quiet.

The two Canadians were taken to a cave where Mao lived. Mao greeted his guests with a smile and embraced Bethune. Drinking tea and eating peanuts, they talked for hours, with Ewen translating, about the wars in China and in Spain. They also discussed the need for good medical care for Mao’s soldiers.

It was decided that Bethune’s medical skills were most needed at the front, some 200 miles to the north. Ewen was sent off to buy medicine but was unable to make her way back. “In this great area of thirteen million people, and 150,000 armed troops, I am the only qualified doctor,” Bethune wrote to friends. “The Chinese doctors have all beat it. My life is pretty rough and sometimes tough as well.”

Becoming A Hero In China

In China, Bethune’s most important invention was a mobile medical unit that could be transported in wooden cases on the back of a donkey. The cases contained a folding operating table, 25 wooden legs and arms to replace severed limbs, and supplies for 100 operations. The staff accompanying these units could go into action within 30 minutes of arriving on the scene.

Bethune spent his days frantically treating patients who had “old neglected wounds of the thigh and leg—most of them incurable except by amputation” and who, he said, were “dying of sepsis.” On one occasion he performed 71 operations in 40 hours with the help of two assistants he had trained. He even found time to give classes in basic medical care and to write a textbook.

Working long hours and constantly on the move, sleeping in peasant huts full of lice, and getting frostbite had a disastrous effect on Bethune’s health. He lost 30 pounds and looked much older than his 49 years, but he told friends he hadn’t been as happy for a long time. In less than two years Bethune became a hero in China. He was nicknamed Bai Qiu’en, which means “White One Seeking Grace.”

On October 28, 1939, as he worked in a mountain village, Bethune cut his finger during an operation. His immune system was weakened, so the wound remained open. In early November he performed brain surgery on a soldier. He had run out of gloves, so his cut came into contact with the man’s highly infected brain tissue. Bethune developed a fever, his finger became swollen, and an abscess appeared in his armpit. On the morning of November 12, Bethune died in a tiny hut in the village.

“The Heavens Wept”

Bethune left a note saying that he knew he was dying and that his only regret was that he was not able to do more. The note ended: “The last two years have been the most significant, the most meaningful years of my life. Sometimes it has been lonely but I have found my highest fulfilment here among my beloved comrades.”

His devoted translator wrote: “Our doctor died on the night of many stars in the sky. The heavens wept.”

When Mao Zedong learned of Bethune’s death, he wrote a eulogy in which he called him a martyr who selflessly supported the cause of the Chinese people’s liberation. Mao urged every Communist to learn from him. During the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s, the eulogy was made compulsory reading in every school in China.

Bethune is buried in the city of Shijiazhuang, and his grave has become a place of pilgrimage. Nearby is the Norman Bethune International Peace Hospital and a museum. It contains a glass case displaying his typewriter, some medical instruments, and papers—the doctor’s only possessions to survive the war.