‘For miles we fared along the windings of the road, with the ever beautiful waters of Gibbon River at our side, now admiring this, then admiring that. Indeed, this was the very poetry of cycling’

Tired and hungry, their bright blue Army-issue blouses tattered and wet from rain and snow, the men of the 25th Infantry Regiment reached Alliance, Nebraska, on July 4, 1897. They had covered 1,000 miles in 21 days, having mastered the Rockies, crossed the Yellowstone and Little Bighorn rivers and surmounted drifts of hail said to be “fully 8 feet high.” The 20 buffalo soldiers, led by Second Lieutenant James A. Moss, still had another 900 miles to go, including a grueling 200-mile trek through Nebraska’s notorious sand hills. Each man carried his own rations, cooking utensils, blanket, tent and other necessities rarely toted by soldiers in the American West—extra parts for needed repairs and spare tires. Yes, tires, because these St. Louis–bound soldiers from Fort Missoula, Montana, were sitting tall on bicycle seats not saddles.

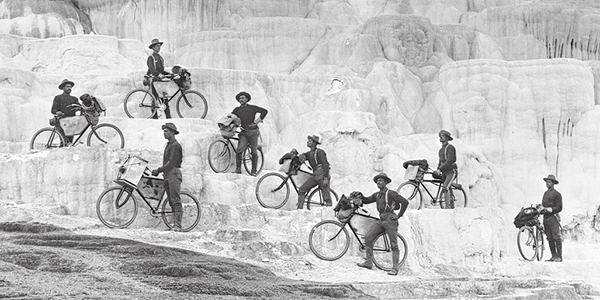

The 25th was one of four regiments of black soldiers enacted by Congress in 1866 and led by white officers. The U.S. Army had established Fort Missoula (now part of the city of Missoula) in 1877, and the men of the 25th first arrived there in May 1888. Eight years later Maj. Gen. Nelson Miles gave Lieutenant Moss—sanguine in his view of modernizing the Army—permission to organize the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps to test the practicality of the bicycle for military use in mountainous country. Moss, a Louisiana native and West Point graduate, wanted to show that cycling was faster than marching and cheaper than traveling on horseback. In early August 1896 he and eight volunteers, including trusted Sergeant Mingo Sanders, made their first excursion, pedaling north to McDonald Lake in the Mission Mountains—a four-day, 126-mile round-trip. Later that summer Moss led a 23-day, 800-mile bicycle trek from Fort Missoula to Yellowstone National Park and back again. “Again and again would we stop along the road to look at paint pots, pools, springs, geysers, etc.” Moss later recalled one particularly fine day in the park:

Riding through the Gibbon Meadows, we then turned off into Gibbon Canyon, deep, sinuous and picturesque. For miles we fared along the windings of the road, with the ever beautiful waters of Gibbon River at our side, now admiring this, then admiring that. Indeed, this was the very poetry of cycling.

While both 1896 jaunts were successful, Moss realized he must try a longer, more grueling trek to prove the true worth of the bicycle. The 1897 trip to St. Louis, about 1,900 miles one way, was the ultimate test ride.

Moss didn’t dream up the bicycle idea in a vacuum; a cycling craze was sweeping the nation. In 1880 enthusiasts had formed the League of American Wheelmen, which lobbied for road improvements and promoted the advantages of the bicycle. The invention of the “safety bicycle,” sporting two wheels of equal size, provided the catalyst to power the craze. Safety bicycles were easier to ride and safer than the earlier cumbersome “penny-farthings,” with one large wheel and one small one. In 1895 Theodore Roosevelt, then president of the board of New York City Police Commissioners, created what became known as the “Scorcher Squad,” a unit of 29 police bicyclists who pursued runaway horses and nabbed reckless carriage drivers. By that time the cycling phenomenon had carried into the Rockies, and bicycles were the talk of the town in Missoula. “Half of the people at the fort are on bicycles, and a person without a wheel is out of the times, as it were,” the Daily Missoulian reported in the spring of 1894.

Military use of the bicycle dated back as early as 1886, when Germany field-tested a bicycle corps. At first it was just a courier service, but the German army later mounted orderlies, scouts and shock troops on bicycles. By the time the U.S. 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps was testing this new mode of transport, other European nations, England and France among them, had followed Germany’s lead and were using bicycles for certain military functions. It helped that the roads in Europe were kinder to two-wheeled vehicles than the largely primitive roads in the American West.

A.G. Spalding & Co. of Chicopee Falls, Mass., made the bicycles for the 25th’s expedition to St. Louis, just as it had for the 1896 trials. The company was at the forefront of bicycle design. Built to Moss’ specifications to handle the rigors of the road, its military two-wheelers were fitted with steel rims, puncture-proof tires, reinforced forks and enclosed gear cases that protected the chains from dust and debris. Each bike weighed 32 pounds, riderless. While the Army and the men of the 25th approached the long journey as a test, Spalding seized it as an opportunity to showcase its bicycles.

Moss and the buffalo soldiers, accompanied by post surgeon James M. Kennedy and Daily Missoulian reporter Edward “Eddie” H. Boos, left Fort Missoula at dawn June 14, 1897. At midday a heavy rain pelted the riders, and the next afternoon bad roads and another downpour forced them off their bicycles to slog along on foot—an inauspicious beginning to their overland odyssey. On their fourth day out, as the men climbed into the Rockies, rain turned to blinding snow, and they couldn’t see past 20 feet. The steep descent presented more danger; Moss and his men had to walk their bicycles, all the while digging in their heels, lest they lose their footing and plummet downslope. Surely, they must have breathed a collective sigh of relief once the Continental Divide was behind them. But more challenges lay ahead.

Stretches past Montana’s Beaver Creek were impassible, compelling the soldiers to shoulder their loaded bicycles. In the Gallatin Valley overflowing wastewater from roadside irrigation ditches splattered the soldiers’ boots. As the riders approached Bozeman, many took what Boos described as “a header over handlebars” on a deeply rutted descent. In Big Timber an old Union veteran insisted every trooper have a drink on him.

While riding between towns, the corps by necessity dispensed with any semblance of formation. Each rider pedaled a path that suited him. Some caught a wagon wheel rut and stayed with it, while others steered a zigzag pattern to avoid rocks. The line of troops often strung out, opening up miles between the lead rider and last straggler. But before entering each town, the men would regroup and strike formation, to emphasize they were a military unit and not just black bicyclists roaming the land.

Boos painted a colorful picture of the procession—“hot and flashing storms” beset the men, “mud covered wheels until they were discs of gumbo,” and “rumors of rattlesnakes broke up uncomfortable camp and started the line in the middle of the night.” Moss also kept a journal on the trek. Each soldier strapped his knapsack, blanket roll and tent to the head of his bike, his haversack to the horizontal bar. Every other soldier carried a carbine, strapped horizontally to the bike’s two upright bars, while the alternating riders hauled canvas-covered boxes with extra supplies. Quartermaster units had placed food drops every 100 miles, but the riders soon discovered that two days’ supply of rations provided just four meals, not six—which often left the “Handlebar Infantry” with hunger pangs. From camp on June 24 Moss reported the men had ridden 42 miles on “a cup of weak coffee, partially sweetened, and a small piece of burnt bread.”

On June 25, its 12th day on the road, the column reached the Little Bighorn, resting amid the ghosts of George Custer’s 7th U.S. Cavalry on the anniversary of its infamous defeat. The next several days brought fair weather, inspiring the men to pedal at a quickened pace. They made good time across northeast Wyoming and through the southwest corner of South Dakota to the Nebraska state border. There, however, they faced the dreaded sand hills, a “soft, shifting mass of sand,” Boos wrote, that compelled them to follow railroad tracks that paralleled their route. As they thumped along the crossties, jarring their wrists, shoulders and backs, they faced temperatures up to 110 degrees. Adding to their misery, drinking water tinctured with alkali soon had three-quarters of the troop doubled over, sick. Moss himself was bedridden for four days, leaving the troop in Dr. Kennedy’s temporary command.

Road conditions continued to vex the cyclists. Moss wrote that roads they encountered were often “a disgrace to civilization,” while Boos added, “The only choice of roads narrowed to bad ones and others that were worse.” Regardless, the column rolled along through such Nebraska burgs as Broken Bow, Germantown (today’s Garland) and Lincoln. Somewhere in Missouri, Boos asked a farmer for permission to camp on his land, and the man asked whether they were Union soldiers. “Why, I guess we are,” the reporter replied, though three decades had passed since the Civil War. “Then you can pile right offa this land,” the farmer snapped back. As the cyclists moved on, a voice called out, “You can camp down there below the pig sty!” Moss and his men decided to push on.

On the rainy morning of July 24, the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps rolled across a railroad bridge on the Missouri River at St. Charles. The clouds soon broke, and they covered the last few rough miles to St. Louis under a broiling sun. On the city outskirts hundreds of local cyclists pedaled out to greet them and form an escort. At 6:30 that evening, after 40 days and 1,900.2 miles, the trek officially ended. Moss was pleased with the results—the troop had averaged 6.3 mph and more than 50 miles each day. Over the next week bicycle clubs feted the buffalo soldiers, and the color barrier seemed to evaporate.

Moss wanted to further test the corps before returning to Missoula. But Maj. Gen. Miles, while applauding the gung-ho lieutenant for a job well done, remained unconvinced of the military value of a bicycle corps. Absorbed in Indian matters, he ordered the 25th back to Montana by rail. The buffalo soldiers, according to Private Richard Rout, still had those trying Nebraska sand hills on their minds and were happy to board the train.

Although disheartened, Moss did not lose confidence. “The trip has proved beyond peradventure my contention that the bicycle has a place in modern warfare,” the lieutenant told the Army & Navy Journal that summer. “In every kind of weather, over all sorts of roads, we averaged 50 miles a day.” Moss further pressed his cause in the interview: “The practical result of the trip shows that an Army bicycle corps can travel twice as fast as cavalry or infantry, under any conditions, and at one-third the cost and effort.”

The bicycles suffered damage to the tune of 17 tires and a half-dozen broken frames, which seems reasonable given the demanding ground the riders covered. But the corps quickly handled most of its own repairs, thanks to Private John Findley, who had spent four years as a mechanic for Ames & Frost’s Imperial bicycle works in Chicago. If a disabled bike needed more work, Findley would give up his own wheels to a rider so the column could continue. Once he had completed the repairs, Findley would pedal the repaired bike like a demon to catch up with the others.

In an age when cavalry remained in use, Moss underscored the bicycle’s clear advantages over the horse. “It does not require as much care,” he explained. “It moves much faster over fair roads…and can be hidden from sight more easily. It is noiseless and raises but little dust, and it is impossible to tell direction from its track.” He concluded, “Under favorable conditions the bicycle is invaluable for courier work, scouting duty, road patrolling, rapid reconnaissance, etc.”

Moss did include caveats in his official report. He emphasized that each rider, not every other one, should have a carbine strapped to his bicycle. Brakes should be mandatory, to avoid those “header over handlebars” spills. He advocated some sort of shock-absorbing device on the handlebars to reduce the pounding riders took on the bicycles. Moss also pressed for increased rations and suggested that when traveling over harsh terrain, the soldiers should dismount and walk their bicycles in formation.

Despite Moss’ convictions, the Bicycle Corps went the route of the U.S. Camel Corps—nowhere. In the mid-1850s Secretary of War Jefferson Davis had peddled the idea of using camels on military campaigns in the desert Southwest (see related book review), and the Army had actually imported a number of the humped beasts. But with the outbreak of the Civil War the experiment unraveled, and the camels were left to roam the desert. After the 1897 Bicycle Corps expedition to St. Louis, Moss was less willing to turn the 25th’s wheeled mounts out to pasture. In 1898 he was in the planning stages of another bicycle mission—from Fort Missoula to San Francisco—when the Army suspended further tests due to the brewing conflict with Spain. Indeed, the Spanish-American War broke out that April, and the Army sent the 25th Infantry to serve in Cuba—but not on bicycles. The U.S. Army did adopt a two-wheeled vehicle in 1913, and in 1916 an expeditionary force under Brig. Gen. John J. “Black Jack” Pershing used that same vehicle to hunt Pancho Villa in Mexico. It was called the motorcycle.

David McCormick of Springfield, Mass., relied on contemporary newspaper articles. He recommends a 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps blog and a visit to the Historical Museum at Fort Missoula. Also see Kay Moore’s book The Great Bicycle Experiment (see review).