As the sun rose over South Africa’s Pretoria Gaol on the morning of Feb. 27, 1902, two British army officers walked hand in hand across the yard toward a pair of straight-backed chairs. The pair had been convicted of committing acts counter to “the rules of civilized warfare”—to wit, murder. Specifically, they had shot or ordered the shooting of unarmed Boer prisoners, some of whom had surrendered under a white flag. Court-martialed for the killings, the officers—Lieutenants Peter Joseph Handcock and Harry Harbord “Breaker” Morant—had been sentenced to death by firing squad.

Once seated, the pair stared down the dark muzzles of 18 Lee-Metford rifles. According to Australian lore, as his executioners prepared to fire, Morant shouted, “Shoot straight, you bastards! Don’t make a mess of it!” These words have long been quoted in chronicles, novels, stage productions and, finally, in the tragic climax of a highly romanticized 1980 feature film.

In fact, the “last words” story is almost certainly apocryphal, part of the mythos surrounding one of Australia’s most controversial figures. From Morant’s birth to the day he was shot, his life story was embroidered with half-truths, legends and outright lies. Even his name was a fiction of his own inventing.

The man who would become known as Harry Morant was born Edwin Henry Murrant on Dec. 9, 1864, the son of a union workhouse manager and matron in Bridgwater, Somerset, England. The young man of humble origins later appropriated the Morant variant of his surname from a prominent British admiral, with whom he falsely claimed kinship as an illegitimate son.

In 1883, Harry Morant migrated to Australia, where he spent the better part of the next two decades working his way across outback Queensland, New South Wales, and South Australia in a bid to further reinvent himself. He was widely known for his skill at taming wild horses, a talent that earned him the nickname “The Breaker.” It was under that sobriquet The Bulletin, a respected Sydney journal, published his widely read verses.

As some of his verses allude, the handsome, roguish Morant had a taste for high living and seldom let a lack of funds discourage him. He repeatedly defaulted on debts, on at least one occasion professing to be awaiting a check from fictional wealthy relatives. By the eve of his 35th birthday in 1899, his carefree, hard-drinking lifestyle had taken a toll. His debts were mounting, his credit was in tatters, and—charmer though he was—he had worn out his welcome in his usual haunts. The timing, however, was propitious. The Second Boer War had just begun.

Seeking to maintain control of the African corner of its far-flung empire, Britain was waging what historians have described as a “dirty little war” against the independent Boer (Afrikaner) republics of the South African interior. As elsewhere in the empire, British authorities in the Australian colonies put out the call for volunteers, and Morant jumped at the opportunity for distinction in the field.

After penning a “Departing Dirge” for The Bulletin, he enlisted in the South Australian Volunteer Contingent for service in South Africa. Before the volunteers shipped out, the Jan. 27, 1900, edition of Adelaide’s South Australian Register listed all the members of the contingent along with a pocket biography of each man. Lance Cpl. Morant’s fanciful write-up lists him as the “son of Vice-Admiral [Sir George Digby] Morant” and states he was born in Devon, England, in 1870.

On reaching Africa, Morant served with distinction as a dispatch rider and war correspondent, though when his six-month term of enlistment expired in July, he happily mustered out. His commanding officer wrote him a sterling letter of recommendation, stating in part, “Your soldierly behavior and your continual alertness as an irregular carried high commendation—and deservedly—from the whole of the officers of the regiment.”

After collecting his final pay and a bonus, Morant sailed to England, hoping for a measure of forgiveness from his creditors. He received none, but while there he struck up a friendship with fellow veteran Capt. Percy Frederick Hunt. The two were to forge a brotherly bond, and through no fault of Hunt’s their emotional ties would prove Morant’s undoing.

Morant and Hunt returned to South Africa in early 1901 and received commissions—Hunt as a captain, Harry a lieutenant—in the Bushveldt Carbineers (BVC), a recently formed British regiment of irregular mounted infantry. By that point in the war the British high command believed victory was imminent. After all, British troops had taken the major population centers, and the Boers’ currency had been rendered virtually worthless.

That said, back in August 1900, having led his men to victory in the set-piece Battle of Bergendal, Field Marshal Lord Roberts had preemptively declared the entire South African Republic a British territory. He, too, had not reckoned on the Boers’ stubborn refusal to quit. The main body of the Afrikaner army remained intact. Reorganized into small, mobile units known as commandos and led by highly competent field officers, the Boer fighters transitioned the conflict into a classic guerrilla war that would last another two years.

The cumbersome British regular forces were ill equipped to successfully counter the Boer partisans. By the turn of the 20th century, the Afrikaners had been living off the land for more than two centuries, and they knew the terrain well. After ambushing the British, the commandos simply melted back into the bush. And while the Boers could count on replenishing their supplies at the farms of friends and relatives, the British had to rely on steam-driven trains and lumbering supply columns, both of which made easy targets.

It soon became obvious to British commanders they would need a radical new approach were they to end the war swiftly and favorably. In October 1900, Gen. Lord Horatio Kitchener assumed command of British forces in South Africa, and he and his staff soon formulated a two-part campaign plan.

The first part proved an unmitigated public relations disaster. Resolving to separate the Boer fighters from their civilian supply sources, the British herded tens of thousands of civilians from their homes and farms—which were then burned, the crops and livestock destroyed—and concentrated them in fenced-in camps, giving rise to the chilling term “concentration camps.” However effective, Kitchener’s plan seemingly failed to consider such essentials as sanitation, clean water, and proper and sufficient food. Nearly one-third of the 94,000 Boer detainees died of starvation, malnutrition or disease, with children suffering disproportionately.

Part two of the plan involved the widespread use of irregular army units. In imitation of the enemy, British irregulars were to live off the land and remain highly mobile, functioning with a minimum of logistical support. As part of his strategy Kitchener erected some 8,000 blockhouses linked by thousands of miles of barbed wire, thus sectioning South Africa’s Transvaal region into grids. It fell largely to the newly created irregular units to clear the grids of resistance. Regiments such as the 1st and 2nd Kitchener’s Fighting Scouts, Steinaecker’s Horse and the Bushveldt Carbineers were tasked with pacifying the Northern Transvaal.

Formed as the Bushveldt Mounted Rifles, the BVC was based in Pietersburg, with detachments at Strydpoort and Fort Edward in the Spelonken region, where Morant, Hunt and Handcock—a self-described “poorly educated” blacksmith from New South Wales—were stationed. Although officially a British regiment, it comprised predominantly Australians, with smatterings of Canadians, Americans, New Zealanders, Germans, Rhodesians, British and a handful of disaffected Boers. All but two of the unit’s officers were Australian.

Oral tradition has elevated the BVC to the level of a highly disciplined anti-guerrilla force, but that was far from the reality. According to a historical sketch by the Australian War Memorial, by the time Morant and Hunt were commissioned, “the carbineers…had already acquired a reputation for shooting prisoners, looting and insubordination.”

The soldiers in the BVC were expected to be expert riders and shooters, though such was not always the case. “A sicker or sorrier crowd of men…would be hard to picture,” one enlistee recalled. “Some had been thrown and lamed through their being bad riders and the horses unbroken. Some had never ridden a horse before, and you know what a 25-mile ride is on a novice.”

Initially, Morant was a welcome addition to the unit—gregarious and charming, a fine horseman and a competent officer. One night in early August 1901, however, a terrible incident occurred that would abruptly change his outlook.

Percy Hunt was a seasoned soldier, having served for years in various British regiments. The captain commanded one of the BVC’s two squadrons. In late July word had arrived that a large band of guerrillas was ensconced at the farmstead of a high-ranking Boer officer. Hunt led out a patrol of a dozen Carbineers and a support contingent of armed “black fellows,” arriving at the farm on the night of August 5. Though forewarned that the house, perched on a rocky kloof (ravine), was impregnable, the captain nonetheless elected to charge the stronghold. The attack went horribly awry. Hunt was shot in the chest almost immediately—though he managed to dispatch the Boer commander—and a sergeant was killed while attempting to retrieve the captain’s body.

By the time Hunt’s body was recovered, it had been stripped of all clothing and—according to an initial report—mutilated. “Morant interrogated several [of Hunt’s] men,” Lt. George Witton later recalled. “They were all positive that [Hunt] had met with foul play.…His neck had been broken, as his head was rolling limply about the cart when he was being brought in. His face had been stamped upon with hobnailed boots, and his legs had been slashed with a knife.” However, a trooper in Hunt’s squadron later testified that the initial report on the condition of Hunt’s body was mistaken.

The discrepancies in the accounts are hard to explain. Natural postmortem effects such as livor mortis (the pooling of blood in the lower portion of the body) can be mistaken for bruising, though that doesn’t explain the deep cuts or broken neck. Regardless, Morant heard the horrific initial report—though he never saw Hunt’s body—and the news greatly distressed him. While attempting to address the assembled carbineers, he broke down and was unable to continue.

From that point on Morant set himself on a dark course. Word had long circulated among the BVC and other units that orders from the highest levels mandated the execution of Boer prisoners. In the wake of Hunt’s death Morant avidly pursued the practice—not from any sense of military justice, but out of a desire for revenge.

Hunt’s death put Morant in command of the squadron, and he immediately assembled a 45-man expedition to pursue those who had killed his friend. The men traveled light and rode fast, soon catching up to a commensurate force of Boers camped along a river. Morant sent a detachment on a flanking movement, but before it was able to get in position, the overanxious, embittered lieutenant ordered the main body of his men to fire.

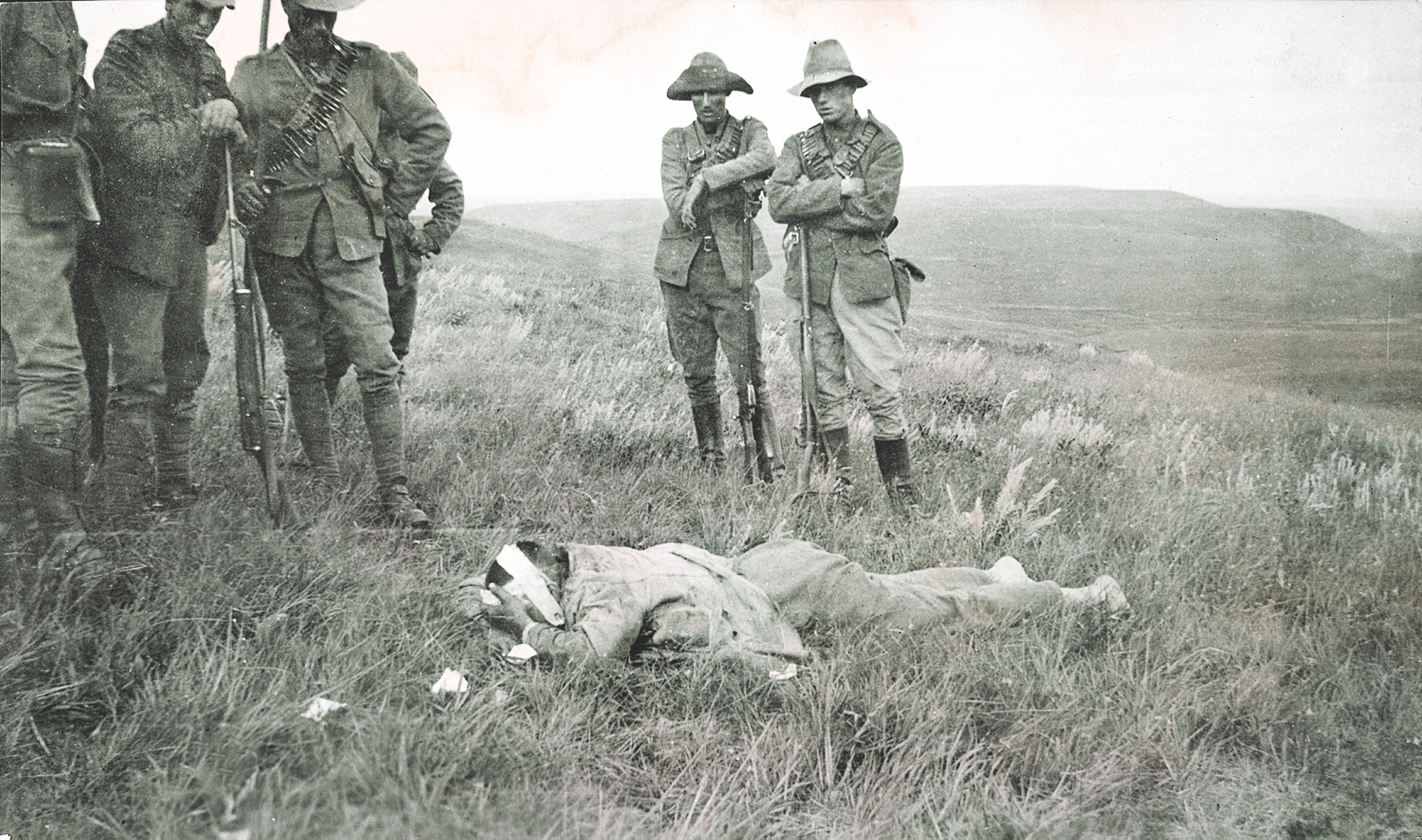

Predictably, most of the Boers escaped, leaving behind one young man, Floris Visser, who had suffered a crippling ankle wound. Morant, with the verbal support of Handcock, ordered Visser summarily shot, precipitating a chorus of objections from several of the men. When told by a mate refusal could lead to his arrest, one trooper responded, “I’ll go prisoner, but I’ll not shoot a wounded man.” Another later wrote, “Shooting an innocent man that cannot stand to take his death awakes big feelings in most hearts, and more than one lanky Australian swore with a gulp that justice should peep into this.”

When one of Morant’s officers presented the men’s objections, the lieutenant replied, “You didn’t know Captain Hunt, and he was my best friend; if the men make any fuss, I will shoot the prisoner myself.”

Another unwritten order purportedly in circulation specified execution for any enemy combatant caught wearing British khaki. Hunt’s tunic and trousers had turned up in the cart beneath which Visser was hiding, but the prisoner had not been wearing it. Trooper James Christie pointed this out to Morant. “I said that Captain Hunt had died a soldier’s death—that he had died in a ‘fair go,’” Christie later testified. Morant replied, “It’s got to be done.” A firing squad was quickly assembled, and Visser was dispatched without preamble. Morant then led the patrol back to Fort Edward. According to Christie, Morant’s subsequent report read in part, “I regret to say that the wounded Boer, captured by us, died of his wounds.”

Before Hunt’s death Morant had not been in favor of executing prisoners, and it is difficult for supporters to justify his apparent shift in approach. Those who knew him well, however, revealed darker aspects of the Breaker’s nature. Two young sons of a rancher for whom Morant had worked in Australia later recalled their fear of him, claiming he regularly abused aboriginal ranch hands. One close friend observed that when sober, the lieutenant presented a polished manner, but when drunk, he repelled polite society. He also acknowledged a dark side to Morant always lurking just below the surface. Hunt’s violent death apparently had called forth that dark side with a vengeance. Tellingly, Witton noted that Morant’s superior, Maj. Robert William Lenehan, “thought, as did others, that Morant’s mind had become unhinged with grief.”

Morant was on a singular mission—to avenge his late friend. “Captain Hunt told me not to bring in prisoners,” the lieutenant himself stated during his subsequent court-martial. “I did not carry out those orders until my best friend was brutally murdered.” A BVC trooper and witness to the killings of prisoners later confirmed that swing in temperament, testifying, “Morant had always treated prisoners well, till Hunt’s death, and then he became a different man altogether.”

Less than two weeks after the captain’s death, Morant reported to Lenehan on the progress of his punitive patrol. “We’ve killed 13 of them up to date now—and that crowd haven’t a blanket left to wrap themselves in,” he wrote. “News comes in every day of small parties of Boers; and out we go to harry them like bloody cattle dogs.”

Six days later Lts. Morant, Handcock and Witton, in company with a sergeant and two troopers, intercepted a BVC patrol returning to the fort with eight Boer prisoners, four of whom were schoolteachers. “Morant said that it was his intention to have the prisoners shot,” Witton recalled. “Both myself and Sgt. Maj. Hammett asked Morant if he was sure he was doing right. He replied that he was quite justified in shooting the Boers; he had his orders, and he would rely upon us to obey him.” As the firing party was forming, one of the Boers made a grab for Witton’s rifle barrel. “I simplified matters by pulling the trigger and shooting him,” the lieutenant recalled, describing the man as a “notorious scoundrel.” The other seven, two of whom Handcock personally dispatched, soon followed him in death.

A German missionary, the Rev. Carl August Daniel Heese, had been observed conferring with the prisoners before they were shot. It was later alleged that after closely questioning the clergyman, Morant ordered Handcock to follow and kill Heese, lest he report the execution to British authorities. In the lead-up to the court-martial Handcock had reportedly broken down and confessed to the missionary’s murder, but at Morant’s urging later withdrew his confession, claiming he had spent the afternoon lunching with the wives of two absent Boer guerrillas. Surprisingly, the women confirmed Handcock’s latter account.

In early September Morant and Handcock led a five-man patrol that intercepted a Boer and his two sons, aged 12 and 17. They were coming in to Fort Edward to surrender, as the teen was ill and needed medical treatment. Morant gave the sick boy a drink of brandy, then ordered all three shot.

Still other executions were attributed to Morant, though he was not the only BVC officer to have killed civilians. Around that time Lt. Charles Hannam led a patrol that encountered three Boer wagons also bound for Fort Edward. When called on to surrender, its panicked occupants bolted, and Hannam’s men opened fire, killing two boys, aged 5 and 13, and shooting a 9-year-old girl through the neck.

By early October the BVC troopers and NCOs had had enough, and 15 of them wrote, signed and sent a letter of complaint to the commanding British officer at Pietersburg regarding their officers. It itemized each incident and listed the names of those responsible. In short order military authorities arrested several BVC officers. “The arrests,” wrote Trooper Christie, “comprise one major, one captain, five lieutenants and one sergeant major. Such a spectacle has never, I hear, taken place in the annals of the British army.”

A court of inquiry led to a series of courts-martial. In accordance with regulations at the time, the official British military records were never made public and ultimately destroyed. But period newspapers offer context, and those in attendance provided ample documentation for a detailed account of the proceedings.

After hearing evidence for four weeks and deliberating for another two, the court of inquiry brought murder indictments against four lieutenants—Morant, Handcock, Witton and Picton—while other senior officers, including Lenehan, awaited trial on lesser charges.

Representing the defendants was Maj. James Francis Thomas, a country solicitor from New South Wales. Unwilling to leave his fate in the hands of the “bush lawyer,” the volatile Morant often opted to speak for himself, which helped his defense not at all. In one instance, when asked whether he had conducted a proper inquiry prior to having young Visser executed, Morant blurted out, “We were out fighting the Boers, not sitting comfortably behind wire fences; we got them and shot them under Rule .303 [a reference to the caliber of the Lee-Metford rifle].”

Each of the accused was tried separately. In his summation regarding the case of the eight executed Boers, defense counsel Thomas argued, “The action they respectively took in the summary execution of these eight Boers was justifiable, or, at any rate, not criminal.” After describing some of the depredations committed by Boers, Thomas concluded, “Upon such an enemy I maintain our troops are justified in making the severest reprisals and are entitled to regard them not as lawful belligerents at all, but as outlaws.”

The court disagreed. On Feb. 26, 1902, after a lengthy trial and intense deliberation, the six-judge panel found all four defendants guilty: Morant of three murders, Handcock of two murders and one manslaughter, and Witton of one murder and one manslaughter. In the case against Morant and Handcock for the murder of the Rev. Heese, thanks in large part to the testimony of the Boer women, the court found the “plea in evidence was not sufficient to convict.” Picton was judged guilty of one manslaughter and cashiered. The other three were sentenced to be shot.

Lord Kitchener ultimately commuted Witton’s sentence to life imprisonment, “in consideration of his having been under the influence of Morant and Handcock.” Released after little more than two years, he later authored the memoir Scapegoats of the Empire, a scathing, self-justifying and heavily slanted indictment of the court, the British army, and the governments of both England and Australia.

The argument has persisted that Morant and Handcock were betrayed by their men, condemned by a one-sided court, abandoned by an Australia seeking to cement its recent status as an independent nation and doomed by a British empire anxious to smooth the path toward a swift peace. Within the past decade defenders even petitioned the Australian government to pardon Morant, Handcock and Witton, based on “fatal flaws in the arrest, investigation, trial and sentencing of the accused.” While their petition was rejected in 2012, such defenders continue to point to Witton’s jaundiced account as the beacon directing their argument.

Among other allegations, Witton claimed the courts-martial were conducted in absolute secrecy, deeming them “the greatest farces ever enacted outside of a theater.” In fact, the trials were publicly held, and whereas most courts-martial resolved in a matter of days, those of the four lieutenants stretched over some months and were reported to be scrupulously fair. If anything, the court allowed the defense considerable leeway. In the words of Deputy Judge Advocate General Col. James St. Clair, whose legal opinion the court sought immediately following the proceedings, “A heap of irrelevant evidence was admitted by the court on the part of the defense, despite the rule of the judge advocate.”

Defenders of the accused assert the supposedly predisposed court unilaterally dismissed the arguments of their talented defense counsel. But there are problems, too, with this claim. “In the popular myth of Breaker Morant,” biographers Joe West and Roger Roper write, “much has been written on the plucky and heroic defense put up by embattled bush lawyer Thomas in the face of overwhelming odds.” But according to reputable sources, Thomas was at best less than competent, and his defense, West and Roper argue, was “naive, inept and, it might be argued, somewhat preposterous.” For example, the solicitor repeatedly allowed his clients to make self-incriminating statements. Ill-advisedly speaking in his own defense, Morant virtually admitted his culpability, stating, “I am quite satisfied that [the Boers] fully deserved the summary execution they received.” Finally, Thomas knew little about military law, the court at one point dismissing his line of reasoning as “perfect nonsense.”

Thomas’ central argument hinged not on whether the defendants killed prisoners, but on their claim to have done so in obedience to standing orders. There is no question Morant and Handcock ordered and conducted the execution of captured Boers, nor did they deny it; however, they justified their actions by citing verbal orders from Hunt all the way up the ladder to Lord Kitchener. Yet neither they nor Thomas offered any corroboration of that claim during the courts-martial.

Even if proof of such instructions had been forthcoming, British military law gave officers the latitude to disobey unlawful orders. One court directive dating from the Napoléonic era established, “Every officer has a discretion to disobey an order against the known laws of the land.” As murder is clearly unlawful, it follows that any reasonable officer should refuse an order to commit it.

In 1973 Australian film director Frank Shields recorded an interview with 91-year-old Muir Churton, a Boer War veteran and former BVC trooper. Churton had been in the patrol that executed Visser and still harbored strong feelings about the event. “Those men had surrendered under a white flag and had given up their arms when they were shot,” he said. When asked whether he felt Morant and Handcock had deserved their fates, Churton replied, “They were as guilty as sin.”

Eighteen hours after being sentenced, Morant went to his death believing he had been sacrificed by the British war machine. He also went game. On the eve of his execution he penned his final ballad, “Butchered to Make a Dutchman’s Holiday.” One verse reads as follows:

It really ain’t the place nor time

To reel off rhyming diction—

But yet we’ll write a final rhyme

Whilst waiting cru-ci-fixion!

It only adds to his mystique that Morant died bravely, refusing a blindfold and staring down the muzzles of the firing squad. According to Pretoria Gaol warden John Henry Morrow, the condemned called out, “Be sure and make a good job of it!” As romantic a figure as Morant might appear, however, more than a century of research and reflection suggest he had abrogated his responsibilities as a wartime officer to wage a personal vendetta. As for Handcock, far from being the slow-witted dupe portrayed by various historians, he had murdered at least two unarmed men and willingly participated in the executions of several others. From both a military and moral perspective, he and Morant had deserved their fate. When the 18 chosen men of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders fired in unison at the two convicted felons seated before them in the Pretoria prison yard, their rifles dispensed nothing less than justice. MH

For further reading frequent contributor Ron Soodalter recommends Shoot Straight, You Bastards! The Truth Behind the Killing of “Breaker” Morant, by Nick Bleszynski; The Legend of Breaker Morant Is Dead and Buried, by Charles Leach; and Breaker Morant: The Final Roundup, by Joe West and Roger Roper.