Changes in technology and lust for battle information led to the birth of modern American journalism

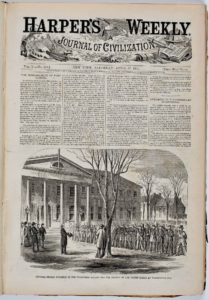

During the Civil War, innovations already under way in technology, business organization, professional practice, government relations, and even reader interest led to great advances in American journalism. The legacy of the Civil War includes the modern mass-circulation daily newspaper, the national illustrated weekly newspaper, and the obsession of readers for both. The war also reinforced the vast disparity of access to media between the North and South.

The telegraph and the railroad, which had been developing rapidly since the 1840s, blossomed during the war. They dramatically transformed how armies conducted warfare and how newspapers and magazines did journalism. Bigger, faster printing presses allowed yesterday’s battle news to be published in today’s newspaper or next week’s illustrated weekly.

In 1861, the New York Herald topped 100,000 in daily circulation. With distribution by rail, the New York Tribune’s national weekly edition achieved a circulation of more than 200,000.

Newspapers and illustrated weeklies became large-scale manufacturing enterprises in the 1860s, presided over by famous editors and publishers such as James Gordon Bennett, Horace Greeley, and Frank Leslie. Nearly as famous—though often still pseudonymous—were the battlefield news reporters, who helped to define the role of “reporter” as a journalistic profession.

In addition to regular daily editions and “extras,” newspapers posted updates on bulletin boards, almost hourly at times. In an 1861 The Atlantic article, Oliver Wendell Holmes captured the new compulsive news habit: “This perpetual intercommunication, joined to the power of instantaneous action, keeps us always alive with excitement….Only bread and the newspaper we must have, whatever else we do without.”

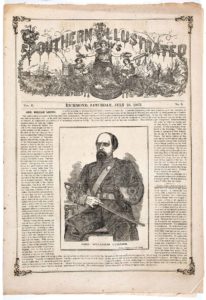

The lust for news was the same for readers in the North and South, but the news industries of the two regions were vastly different. In 1860, less than 10 percent of the nation’s printing establishments were in the South. The South had 70 daily newspapers in 1860, out of 387 nationwide, but those papers accounted for only 10 percent of the national circulation. Only about 20 dailies survived to the end of the war, in part because the South had only a handful of paper mills and no printing-press manufacturers.

In the 1850s, American newspapers employed a few paid correspondents and writers, but it was during the Civil War that newspaper reporting came of age. As war spread across the country, so did legions of reporters. Throughout the war, the New York Herald alone regularly had more than 40 reporters on the fields of battle. Though newspaper reporting had never been a profession that required specialized training or certification, during the war, reporters took on many of the characteristics of professionals: On the major dailies, they were salaried and given lavish expense accounts; they operated independently in the field; lived and worked together in a community of comrades; were supremely competitive yet shared the values that would become standard in journalism: eyewitness description and speed; they resisted military and government censorship; they often became celebrities; and they wrote instant books and memoirs to cash in on that fame.

The art of war reporting, then as now, required a mastery of logistics as well as of reporting and writing. Like the generals, the journalists who covered the Civil War depended on telegraphs, railroads, and horses. The enemy’s task, often achieved, was to destroy those means of communication. Thus, dramatic accounts of reporters getting stories of great battles back to their newspapers became chapters in the lore of American journalism. For example, George W. Smalley of the New York Tribune, unable to get a telegraph connection, wrote what is usually considered the best story of the Battle of Antietam by the light of a small oil lamp on a military train from Baltimore to New York. He arrived at the newspaper office at 5 a.m. September 19, 1862, just two mornings after the battle, and within hours thousands of Tribune copies were on the street.

If reporting for Northern newspapers was a logistical struggle, it was a nightmare for the South. Telegraph and rail connections were sparse and unreliable. Southern newspapers were cut off from the Associated Press, the leading news-sharing cooperative, based in New York. Southern publishers organized their own Press Association in 1862, which did its best to distribute news dispatches.

In addition to newspapers and periodicals, Americans learned about the war from various pictorial sources. While newspapers were illustrated with drawings etched on wood blocks, people could also purchase lithographs in studios and print shops. Lithography was a technology adopted in the 1830s in which an artist drew an image by hand on a special stone, usually a smooth piece of limestone, with a grease pencil or crayon. Water was then applied and would soak in where there was no crayon. An oil-based ink was applied next. The wet stone would repel the ink, but the areas with grease drawing would not. A press transferred ink to paper. Thousands of impressions could be made from one stone.

As lithography grew, it was joined by photography, first with the appearance of the daguerreotype in America in 1839, followed by the more quickly exposed ambrotype and less-expensive tintype in the 1850s. Though these new methods had advantages, their use was still limited. The glass plate or sheet of metal used to capture the image was the photograph, and therefore non-reproducible. The development of the negative-based albumen process, also in the 1850s, eased these impediments to widespread access. This process allowed photos to be reproduced on paper for inexpensive and widespread distribution as carte-de-visite studio portraits and stereographs. Photographers exhibited and sold their work in their galleries. They also used mail order catalogs to distribute photographs and stereographs to distant customers.

This material was originally published with The American Antiquarian Society’s online exhibit, “The News Media and the Making of America, 1730-1865.” The society sponsors a broad range of programs for schoolchildren, undergraduate and graduate scholars, artists, writers, and the public. Visit www.americanantiquarian.org.