At 2 a.m. on April 24, 1862, about a dozen Union ships steamed past the forts at the mouth of the Mississippi River toward New Orleans, the economic and cultural heart of the antebellum South.

Panic coursed through the city and by dawn, foodstuffs, already scarce because of the Union blockade of Confederate ports, were almost impossible to obtain. Banks asked depositors to withdraw their valuables, and two closed for business—not accepting deposits of any kind. Four days of bombardment followed. In a last-ditch effort to stall the Union advance, Rebels loaded a large raft with cotton and wood, doused it with pitch and turpentine, and sent it drifting toward the Union fleet. And then they fled, leaving New Orleans Mayor John T. Monroe to confront the Yankees as best he could.

When Admiral David Farragut and his fleet neared the city docks on April 28, the Union commander sent Mayor Monroe a note demanding “the unqualified surrender of the city, and that the emblem of the sovereignty of the United States shall be hoisted over the city hall, mint, and custom-house.” New Orleans was given 48 hours to comply or the city would be fired upon. Mayor Monroe defiantly responded:

We stand by your bombardment, unarmed and undefended as we are. The civilized world will consign to indelible infamy the heart that will conceive the deed and the hand that will dare to consummate it.

The following day Farragut informed Monroe that with the surrender of Forts Jackson and St. Philip, the city was under Union control. He ordered the mayor to “haul down and suppress every ensign and symbol of government, whether State or Confederate.” Farragut then sent a Marine detachment with two howitzers ashore to remove the Louisiana secession flag from the roof of the customs house. Some in the crowd looked on tearfully, but others, like local gambler William B. Mumford, remained rebellious. Joined by three others, Mumford went to the roof, removed the U.S. flag, then dragged it to the front of City Hall, where they tore it up, distributing the tatters to the mob as souvenirs. Mumford would later pay for this desecration before a military tribunal convened by Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, who arrived with Federal troops to occupy the city three days later.

The transformation of the Confederacy’s largest city had just begun. Butler’s seven-month tenure as military governor of New Orleans would leave a lasting mark on the city, and an indelible and controversial legacy on the national stage. Not only would Butler’s shrewd and decisive governing bring an unruly populace under control, but he would also implement an extensive cleanup that would set a record for public hygiene and disease control. Butler’s administrative genius, however, would be countered by a genius for antagonizing powerful adversaries, not only domestically but abroad. While the capture of New Orleans, for example, appeared to mar the Confederate prospects for diplomatic recognition from Great Britain and France, Butler’s treatment of foreign residents would prove so harsh that it aroused European sympathy for the Confederates instead.

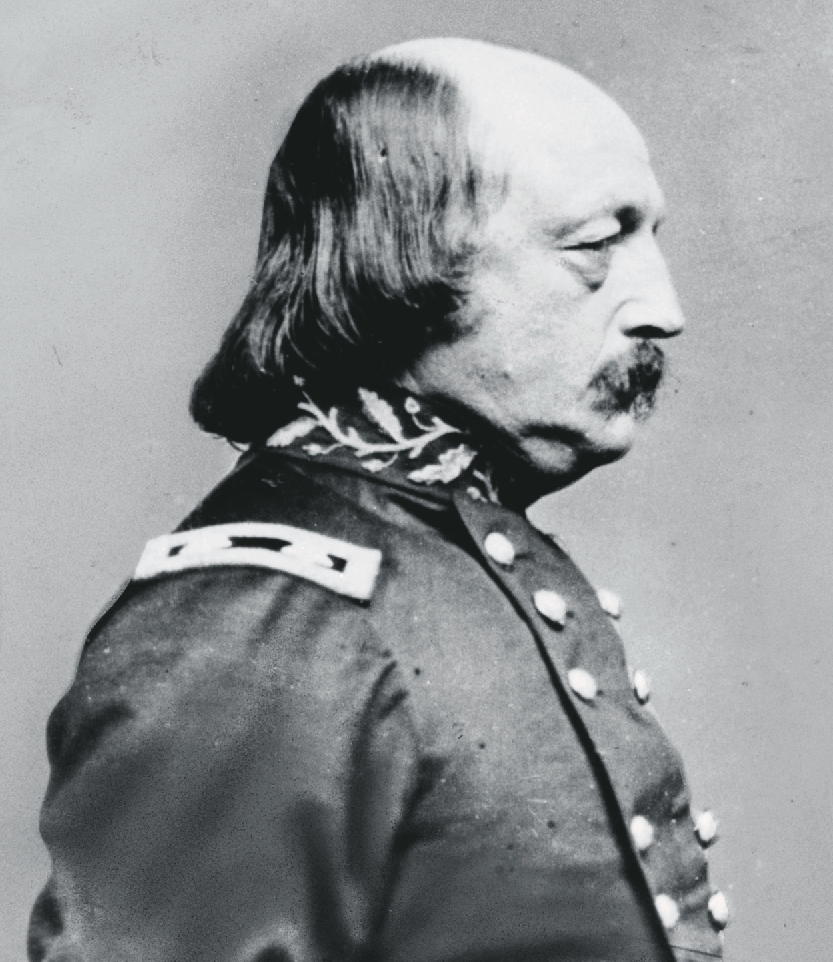

Benjamin Franklin Butler, a successful Massachusetts attorney turned state legislator, was one of several Civil War generals who gained their commands through political appointments. From the start, he was a man of contradictions. As a Democrat, he had briefly thrown his support to Jefferson Davis for the presidency in 1860, believing him to be moderate and statesmanlike. But when war broke out, Butler lined up with those who wanted to preserve the Union, was named a general and quickly earned a reputation for unpredictable, bad behavior. Within weeks of the start of the war, Brig. Gen. Butler had seized Baltimore—without any orders to do so—and arrested pro-secession Maryland officials. President Lincoln was reluctant to chastise an influential Democrat whose actions drew a great deal of support from Northern concerns. Instead, the president offered Butler a commission as a major general, which he accepted.

As commander of the newly created Department of Virginia, Butler began contemplating an advance on Richmond from his base at Fort Monroe, near Hampton. But a humiliating defeat at Big Bethel on June 10, 1861, in which his men were ambushed while attacking a Confederate position, derailed that plan and nearly cost him his commission. In August, Butler was given command of a joint Army-Navy attack on two Rebel forts in North Carolina’s Hatteras Inlet. Though he disobeyed orders during the operation, he forced the surrender of the forts and won popular support in the North. The following spring, he was assigned command of the military expedition to New Orleans—over the protests of Union General in Chief George B. McClellan.

Upon his arrival in New Orleans, Butler issued edicts governing the conduct of both his own troops and the city’s residents. In his General Orders No. 15, he forbade any plundering of public or private property. To the city’s citizens, he laid down martial law:

The commanding general, therefore, will cause the city to be guarded, until the restoration of the United States authority and his further orders, by martial law. All persons in arms against the United States are required to surrender themselves, their arms, equipments, and munitions of war.

Butler demanded that all citizens take an oath of allegiance or risk being “deemed rebels against the government of the United States, and regarded and treated as enemies thereof.” To eliminate any risk of rebellion, he suppressed newspapers that would report troop movements or promote sedition against the United States in any way. And on May 30, Butler made an example of flag-desecrating William Mumford, trying him before a military tribunal. Several witnesses offered evidence against the accused, and Mumford was found guilty of “high crimes and misdemeanors against the laws of the United States, and the peace and dignity thereof.” Despite pleas from Mumford’s wife, Butler issued an order of execution to take place June 7. Mumford stood for his execution without remorse.

To poor and starving people Butler showed a softer side, but only after making clear where he thought the blame for the food shortages lay. In General Orders No. 25, Butler reproached “the vile, the gambler, the idler, and the ruffian” for destroying the foods that had not been seized by the retreating Confederate army. Butler then turned over to the needy food his men had captured from Rebel supplies. “A thousand barrels of these stores will be distributed among the deserving poor of this city, from whom rebels had plundered it,” he wrote. Although historians have asserted that Butler personally received kickbacks from the quartermaster for these goods, no substantial evidence has been found to prove the charge. Butler even used some of his own money to purchase food to distribute. And he was not afraid to impose assessments on wealthy Rebel-supporting businessmen, brokers and planters to support the needy.

After solving the food crisis, Butler addressed a looming threat to his troops. Summer was the season for “yellow jack,” as yellow fever was known in Louisiana. The illness, now known to result from a mosquito-spread virus, was then chalked up to “bad air.” Butler tackled the problem by putting hundreds of unemployed men to work cleaning up heaps of rotting garbage standing two feet deep in some places, and he imposed a quarantine policy on incoming ships.

But his most notorious edict concerned the rebellious ladies of New Orleans who were flagrantly and ingeniously insulting the “Yankee invaders.” One Union soldier witnessed a female who would “contemptuously lift up her skirt, glare at the soldier,” then walk away. Women spat on soldiers as they walked down the street. Even the highest in command was vulnerable. While walking with one of his subordinates in the French Quarter, Admiral Farragut was doused when a woman emptied her chamber pot as they passed beneath her balcony.

To curb this behavior, Butler issued his infamous General Orders No. 28, known to historians as the “Woman Order.” Any woman affronting Union soldiers would be arrested as a prostitute, an order Butler deemed would “execute itself.”

He was right.

“Since that order,” he wrote a Northern colleague, “no man or woman has insulted a soldier of mine in New Orleans.” Southerners, however, denounced the order as “an open invitation to ravage women of all ranks.”

Butler tolerated no loyalty to the Confederacy, and he was particularly committed to punishing any who would aid and comfort the enemy. When he uncovered a plot by Mayor Monroe and some of his staff to smuggle Confederate parolees out of the city, Butler sent them to be held at Fort Jackson.

The people of New Orleans were outraged. One city resident likened Butler and his administration to “the tyrannies of Nero.” A more damaging charge came from one of Butler’s own men. In a letter home, Lieutenant George W. Whittelseip, 13th Connecticut Infantry, wrote that “Butler is a smart and acute man but there is no dependence to be placed on his integrity—he cares more for wealth and fame than for anything else.”

Yet when informed that the wife of a well-known and revered Southern officer was gravely ill and might soon perish, Butler wrote a note offering safe passage if the officer desired to visit her. The favor was unusual, given that sick woman was the wife of New Orleans native General P.G.T. Beauregard, the man responsible for the first shots fired in the war.

Even foreigners in the Crescent City felt the pressure of Butler’s convictions. The European nations with consuls in New Orleans maintained an outward show of neutrality, but their reliance on the South’s cotton for making clothing and other goods gave them reason to be sympathetic to the Confederate cause. When Butler required consuls at foreign embassies to attest that they would not aid or conceal an act that aided the enemy, they collectively protested.

Butler would not be swayed, convinced that wealthy foreigners were subverting his attempts to break the rebellion. His crackdown extended to seizing assets in the vaults of the consulates of the Netherlands and France, which he claimed would be used to benefit the Confederacy. And when he discovered that a fleeing British brigade had given some of their equipment to the Confederate army and that two members refused to leave the city, Butler had the men arrested. The U.S. State Department later ordered them released. On another occasion, Butler had a prominent French champagne distributor arrested after learning he was carrying letters to Richmond while posing as a ship’s bartender. In fact, the Frenchman had come to the United States to collect on debts. Again, Secretary of State William Seward ordered the man released.

Butler’s militancy stood to threaten delicate diplomatic relationships. In August, Seward sent a representative to investigate claims against Butler. The mounting concern led the administration to replace Butler with another politically appointed general, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, who arrived in December 1862 with orders to take a more conciliatory approach to the New Orleans populace. In his 1892 memoir, Butler attributes his reassignment to Seward’s reluctance to alienate the European powers and their commercial interests.

The people of New Orleans rejoiced at the news. “You may reach Yankeedom in safety—but remember, vile old coward, that day will come when you will be hunted down like a fox in your den, and retribution will surely fall upon you,” scolded a woman addressing herself only as one of Butler’s “she-adders” in a December 22 letter. The next day, Jefferson Davis, the man Butler had once backed as a presidential candidate, declared the departing commander “to be a felon, deserving of capital punishment” and “an outlaw and common enemy of mankind,” and ordered any officer who caught Butler to hang him immediately. Richard Yeadon, a Charleston, S.C., businessman offered a $10,000 reward for Butler’s capture, dead or alive.

Never at a loss for words, Butler would not depart without offering a strong defense of his actions. On December 24, he delivered a lengthy and spirited farewell address to the people of New Orleans.

“The enemies of my country, unrepentant and implacable, I have treated with merited severity,” he said. “I hold that rebellion is treason, and treason persisted in is death, and any punishment short of that due a traitor gives so much clear gain to him from clemency from the Government.” Butler named slavery as the evil the people of New Orleans must remove. “Look around you and say whether this saddening, deadening influence has not all but destroyed the very framework of your society?”

The South dubbed Butler “the Beast,” and he was easily among the most hated Union generals in the region. His crackdown on New Orleans, however, proved to be the peak of his military career. After subsequent assignments revealed Butler’s military incompetence and lack of training, Ulysses Grant removed him from command on January 5, 1865. But the controversial commander’s true legacy lies in administrative and policing skills, not in strategy or tactics. He ruled New Orleans with an iron hand, and left the city in far better shape than he found it.

Alan G. Gauthreaux is an adjunct instructor of history at Delgado Community College in New Orleans.