This story is an updated version of one published in the October 1994 issue of Military History.

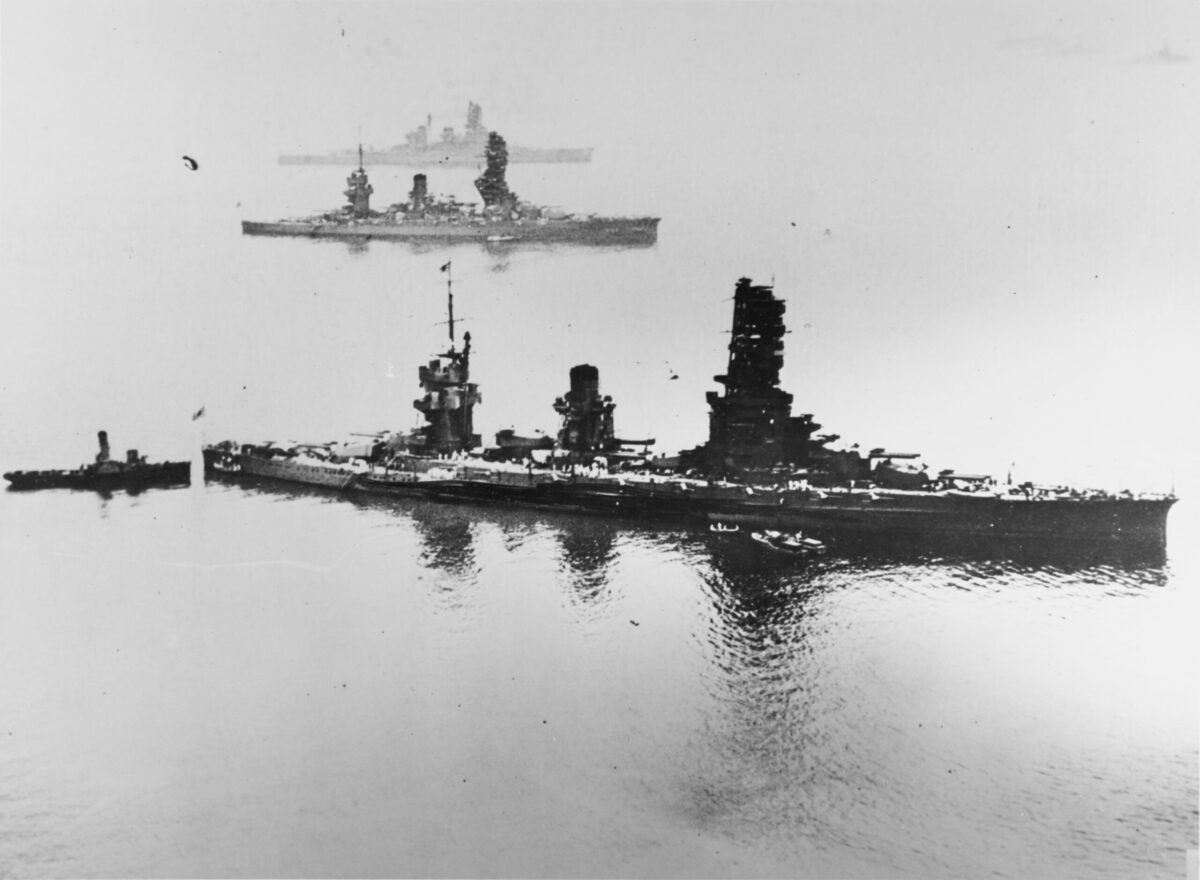

A battleship Arms race

The Battle of the Philippine Sea, fought on June 19 and 20, 1944, left Japan with the bulk of its navy intact but no longer able to oppose the U.S. Navy on equal terms. More serious than the sinking of three aircraft carriers in that action was the virtual decimation of the airmen and aircraft of Japan’s carrier air groups. Even so, Japan still possessed some of the most powerful surface warships in the world. The question now was whether they could ever venture close enough to engage their American counterparts.

Then, on October 20, U.S. Army troops landed on the island of Leyte. General Douglas MacArthur was fulfilling his vow to the Philippines—and here a widespread maze of islands provided the Japanese fleet with a final opportunity to strike at the advancing Americans.

Devised by Admiral Soemu Toyoda and his Combined Fleet staff, Operation Sho-I “Victory 1”) was typically Japanese in its complexity. Essentially, three forces of battleships, cruisers and destroyers were to converge on the American landing site in Leyte Gulf, engaging and sinking any enemy ships on their way to shell the beachhead. The “First Diversionary Attack Force”—in reality, the main force—commanded by Vice Adm. Takeo Kurita, would come from the north, through San Bernardino Strait. Joining it from the south, via Surigao Strait, would be two smaller surface forces commanded by Vice Adms. Kiyohide Shima and Shoji Nishimura.

The fast aircraft carriers of Admiral William F. Halsey’s Third Fleet were to be lured away by a fourth Japanese force, commanded by Vice Adm. Jisaburo Ozawa and including the carriers Zuikaku, Zuiho, Chitose and Chiyoda, steaming off the northern Philippines. With only 118 aircraft between them, Ozawa’s carriers were not expected to achieve much, other than to lure Halsey’s Third Fleet away from Leyte, but its task was essentially sacrificial in nature. If the decoy planned worked, the American naval forces left around Leyte Gulf might be sufficiently weakened to be crushed between the two prongs of surface warships.

Speculation about the practicality of Toyoda’s strategy has been debated ever since, but one factor, more than any others, make its innate futility clear. The U.S. Army had already landed and secured a beachhead on Leyte days before the naval operation was launched. Toyoda and his senior officers knew this, but to them it was beside the point. Unable to countenance watching Japan go down in defeat and surrender its high seas fleet the way the Germans had in 1919 and the Italians in 1943, Toyoda was willing to sacrifice his entire navy just to emblazon in history that it went down fighting.

Even by those parameters, Sho-I got off to a poor start. At midnight on October 23, Kurita’s main force was ambushed in. the narrow Palawan passage by two American submarines. Darter sank Kurita’s flagship, the heavy cruiser Atago, and badly damaged its sister ship, Takao, while Dace sank the cruiser Maya. Darter subsequently ran aground and had to be abandoned. Kurita transferred his flag to the giant battleship Yamato, but it had to be unsettling to lose three of his most powerful ships before even reaching the projected combat zone.

No turning back

On October 24, the U.S. Third Fleet’s alerted carriers launched their planes to go after Kurita’s ships, at the same time fighting off an attack by Vice Adm. Shigeru Fukudome’s Second Air Fleet, joined by most of Ozawa’s aircraft. The Americans lost one light carrier, Princeton, while Yamato’s sister, the battleship Musashi, sank after being hit by 15 torpedoes and 16 bombs. Off to the northeast Ozawa’s carriers, now down to a hopeless 29 aircraft, had still gone completely unnoticed.

Shaken, Kurita turned back, but at 6:15 p.m. he received a message from Admiral Toyoda in Japan: “With confidence in heavenly guidance the combined force will attack.” In essence, it was a chiding reminder to Kurita that retreat was not an option. He turned his force eastward again, unaware that his slim chances of success had taken an arbitrary turn for the better.

Just after 4 p.m., it seems, a scouting Curtiss SB2C Helldiver had spotted Ozawa’s force and reported it to Halsey. Convinced that Kurita’s beating in the Sibuyan Sea had eliminated him as a threat, Halsey took all three of his available carrier task groups and steamed north for Ozawa’s carriers—leaving the San Bernardino Strait almost completely unprotected.

What remained adjacent to the beachhead was the naval force delegated to provide direct support for MacArthur’s amphibious operations, the Seventh Fleet under Vice Adm. Thomas Cassin Kincaid. While it lacked any fleet carriers, the Seventh Fleet had 18 small escort carriers led by Rear Am. Thomas L. Sprague’s Task Group 77.4. Its main punch, however, was a sextet of dated but still powerful battleships, commanded by experienced admirals who knew how to make the most of them.

While Kurita vacillated to the north, two smaller approached Leyte Gulf from the south. The first and most powerful of them was Nishimura’s “Force C,” comprised of the World War I-vintage battleships Yamashiro and Fuso, heavy cruiser Mogami and destroyers Michishio, Asagumo, Yamagumo and Shigure. “Number Two Striking Force,” as the other unit was called, was commanded by Shima and consisted of the heavy cruisers Nachi and Ashigawa, light cruiser Abukuma and destroyers Shiranuhi, Kasumi, Ushio and Akebono.

A modern samurai?

In theory the two groups were to go up Surigao Strait and supplement the tremendous firepower of Kurita’s “Force A.” Several factors, however, would prevent their uniting. First, Nishimura was directly under Kurita’s command, whereas Shima, coming down from the Formosa, was answerable to another superior, Vice Adm. Gunichi Mikawa. Although given vague orders to “support and cooperate” with Nishimura, Shima made no serious attempt to join him, choosing instead to follow him at a distance of 30 to 50 miles.

There were serious temperamental differences between the two admirals, though both were too professional for their mutual loathing to have any real bearing on their failure to combine their forces. Both had grave doubts as to their chances of success—Shima approached the mission with caution and expressed his misgivings; Nishimura was more the more reckless, rushing ahead to either victory or a fighting death worthy of a samurai. On a more practical level, Nishimura was anxious to reach Leyte Gulf before dawn, because he was convinced that his chances of outfighting his adversaries would be better at night—a forlorn hope, since by late 1943 the Americans had much-improved radar capability.

Nishimura’s Force C was first spotted in the Sulu Sea by aircraft from carriers Enterprise and Franklin at 9:05 a.m. on October 24. The planes attacked at 9:18, scoring a bomb hit on Fuso’s fantail that destroyed its floatplanes, while another bomb knocked out the destroyer Shigure’s forward gun turret. Neither ship was slowed, however. At 11:55 a bomber from the U.S. Army’s Fifth Air Force found and reported Shima’s force. Admiral Kincaid now knew the enemy’s strength and his probable course. He delegated the job of dealing with the southern threat to the commander of his Fire Support Unit South, Rear Adm. Jesse E. Oldendorf. Flying his pennant aboard the heavy cruiser Louisville, Oldendorf had three battleships, Pennsylvania, California and Tennessee, at his disposal; they were joined by three more “big boys” from Rear Adm. George L. Weyler’s Fire Support Unit North, Mississippi, Maryland and West Virginia.

Under normal circumstances, Oldendorf’s battle group could pulverize both Japanese formations, but his ships had used up most of their ammunition during the shore bombardment. Oldendorf could not afford an extravagant display of firepower—not if he wished to avoid seeing his mighty battlewagons sunk by Nishimura’s antiques simply because they had no shells left. To make every shot count, he would need accurate information on the enemy’s route up Surigao Strait.

The vital role of intelligence-gathering was assigned to the Seventh Fleet’s patrol torpedo (PT) boats, under the overall command of Commander Selman S. Bowling. That night Bowling’s executive officer, Lieutenant Commander Robert A. Leeson, gathered the 39 boats then available, organized them into 13 three-boat sections, led them south through Mindanao Strait and dispersed them across the northern end of Surigao Strait.

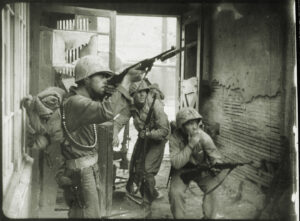

The prospect of action was music to the ears of the PT boat crews. Their primary mission, however, was to lie low and report whatever they saw coming. As night fell they, rather than aircraft, became the eyes of the Seventh Fleet. The weather deteriorated, with frequent rain squalls affecting visibility, by at 10:46 p.m. a section of PT boats lying off Bohol Island picked up something on their radars. Instead of immediately reporting their discovery, however, the PT boats advanced at 24 knots to attack. They were three miles from their intended targets—still beyond torpedo range—when Shigure, survivor of numerous night actions in the Solomon Islands, sighted them. Suddenly, the crack of big guns rent the night and the Battle of Surigao Strait was on.

The battle begins

With shells splashing all around them, the PT boats made smoke and zigzagged as they tried to close on the enemy. Suddenly Shigure’s searchlight fell on PT-152 and in seconds a Japanese shell set the craft afire and killed one of its gunners. PT-152’s skipper, Lieutenant junior grade Joseph Eddin, steered away, as did his two consorts. One of the latter, PT-130, was also hit, a round passing through it without exploding, but knocking out its radio. Once contact was broken off, PT-130 sped over to the next section of PT boats and relayed its contact report to PT-127, which radioed it to the PT- oat tender Wachaspreague. The news reached Oldendorf aboard the cruiser Louisville at 12:26 a.m.

Meanwhile, more of the PT boats converged on the Japanese, engaging them with their 40mm cannons as well as their torpedoes. PT-151 and PT-146 each fired a torpedo at the heavy cruiser Mogami, but both missed. They and PT-190 then fled, pursued by destroyer Yamagumo.

Satisfied with the way things were going thus far, Nishimura reported to Kurita and Shima that he expected to pass Panoan Island at 1:30 and enter Leyte Gulf. “Several torpedo boats sighted,” he said, “but enemy situation otherwise unknown.”

At 2:05, as Nishimura’s force passed Camiguin Point and turned due north, Leeson’s flagship, PT-134, tried to attack but was driven off by intense gunfire. PT-490 tried to attack a destroyer at 2:07 but was hit. One of PT-493’s torpedoes hung on the rack and as it made smoke to cover PT-490’s retirement, it took three 4.7mm shells, possibly from battleship Yamashiro’s secondary battery; the hits killed two men and wounded five others, including its captain, Lt. jg Richard W. Brown, and his executive officer (XO). One of the shells also punched a hole in its hull, but Petty Officer Albert W. Brunelle, described by a shipmate as a “slight sissified-looking boy whom no one expected to be of any use in combat,” stuffed his like jacket in the hole and kept PT-493 afloat just long enough for the crew to run it onto the rocks off Panaon Island. (After wading ashore Brown and his crew were picked up the next morning by PT-491, but the high tide cast PT-493 adrift and it sank in deep water. Brunelle was later awarded the Navy Cross.)

While the PT boats were faring poorly in their efforts to damage Nishimura’s ships, Oldendorf was deploying his force across the northern end of Surigao Strait in battle formation. On the right flank, off the coast of Leyte Island itself, lay destroyer squadron (Desron) 39 led by Captain Kenmore M. McManes aboard Hutchins, and included Bache, Daly, Beale,Killen and the Australian destroyer Arunta. Backing them up were three cruisers, the American Phoenix and Boise and the Australian Shropshire, along with three more U.S. destroyers, Clayton, Thorne and Welles. In the center was Captain Roland M. Smoot’s Desron 56, comprised of flagship Newcome, Richard P. Leary and Albert W. Grant. Immediately to his north was Destroyer Division (Desdiv) 112 under Captain Thomas F. Conley Jr. on Robinson and including Halford and Bryant. To the south were destroyers Heywood L. Edwards, Leutze and Bennion. Farther south, athwart the passage, was Captain Jesse G. Coward’s Desron 54, made up of his flagship Remey plus Melvin, McGowan, McDermut (flagship of Desdiv 108’s Commander Richard H. Phillips) and Monssen. Also waiting in the first American line, due north of Hibuson Island, lay Oldendorf’s flagship Louisville, along with heavy cruisers Portland and Minneapolis and the light cruisers Denver and Columbia. North of them were the destroyers Aulick, Cony and Sigourney. Last but by no means least, forming the backfield, were Oldendorf’s heavy hitters, the battleships Pennsylvania, California, Tennessee, Mississippi, Maryland and West Virginia.

american torpedoes honing in

The last PT boat attack ended at 2:13 a.m. off Sumilon Island. For the loss of three men dead and 20 wounded, the boats had scored no hits, but they had accomplished their primary mission—pinpointing and reporting the Japanese movement. At 2:25, Lieutenant Carl T. Gleason’s PT-327 spotted the enemy 10 miles away and reported the contact to Captain Coward. He in turn ordered Gleason to clear his PT-boat section out of the way, so that they destroyers could engage the enemy. At 3 a.m. Nishimura’s destroyer vanguard ran into Desron 54 and the main event was on. By 3:01, Coward’s “tin cans” had launched 27 torpedoes and begun a zigzagging retirement. Japanese searchlights pierced the night and shells straddled the Americans, but the shoreline blurred the more primitive radar of the Japanese, and no solid hits were scored.

At 3:09 McDermut and Monssen launched 20 more torpedoes from the west. The Japanese fired at those tormentors, too, but again their shells only managed to straddle the American destroyers. Then the American torpedoes began to strike home. One of Melvin’s “fish” ploughed into battleship Fuso’s No.1 turret and another struck it astern, flooding a boiler room and starting a fire. Even with its speed lowered to 12 knots, it developed a starboard list, and at 3:20 it turned south, doing 10 knots. Massive flooding continued and at 3:45 the ungainly battlewagon went down by the bow. Only about 10 of its 1,630 crewmen survived. Their testimony that their ship sank in one piece, not blown in two as per earlier claims, was confirmed decades later when Fuso’s still-intact remains were discovered.

As the torpedoes from Desdiv 108 commander Phillips’ two ships came at him, Nishimura made a half-hearted evasive turn that allowed his flagship to escape Fuso’s fate. One torpedo struck Yamashiro but failed to slow it down. His destroyers were less fortunate. Soon after taking a hit, Yamagumo blew up and sank. A second torpedo left Michishio dead in the water and another blew Asagumo’s bows off. All three hits came from McDermut in the most successful torpedo spread launched by a U.S. Navy destroyer. At 3:30 Nishimura signaled Kurita and Shima: “Enemy torpedo boats and destroyers on both sides of northern entrance to Surigao Strait. Two of our destroyers torpedoed and drifting. Yamashiro hit by one torpedo but fit for battle.” He then single-mindedly pressed on—straight into the waiting clutches of Desron 24.

Again, the Allies attacked in groups of three, Hutchins leading Daly and Bache to loose 15 torpedoes. Farther up the strait, Australian Commander Alfred E. Buchanan of Arunta led Killen and Beale for the second attack—bringing his trio into a closer, more effective range before sending a total of 14 torpedoes at Nishimura.

Recognizing Yamashiro’s distinctive silhouette, Commander Howard G. Corey of the destroyer Killen ordered his torpedoes set to run at a shallower-than-usual depth, 22 feet, before launching his spread. Four of them detonated under the old battlewagon’s keel, breaking its back. While 5-inch shells pelted his crippled flagship, Nishimura issued a general order: “You are to proceed and attack all ships.” At that point, only heavy cruiser Mogami and destroyer Shigure were in any condition to do any proceeding or attacking, but they dutifully steamed on. Somehow Yamashiro’s crew managed to get their ship underway too, plodding on at 15 knots.

Having failed to score any torpedo hits, McManes of Desron 24 circled around Nishimura’s heavies and encountered the crippled destroyers Michishio and Asagumo, which he engaged with gunfire until Rear Adm. Russell S. Berkey, commanding the right flank of Allied cruisers aboard Phoenix, ordered Desron 24 to clear the area because the American battle line was about to commence firing. As his “tin cans” turned northward, McManes’ flagship Hutchins fired its last four torpedoes at Asagumo. They missed it but struck the drifting Michishio, which blew up and sank at 3:58.

Meanwhile, Nishimura’s dwindling Force C ran into Captain Smoot’s Desron 56, the central element of which attacked in two sections (Robinson, Halford and Bryant, followed by Heywood L. Edwards, Leutze and Bennion. After they launched their torpedoes and retired, Smoot, aboard Newcomb, led Richard P. Leary and Albert W. Grant against the enemy formation while the Japanese were turning from a northerly to a westerly course. Following their gun flashes, Smoot led his destroyers on a parallel course to the right of the Japanese and at 4:05 he fired torpedoes at a range of 6,300 yards.

Smoot then had to retire—via one of two unhealthy escape routes. If he went northward, directly away from the Japanese, he would run afoul of the American battle line. Continuing west could take him clear of the American line of fire, but he would still be under enemy fire. Newcomb’s skipper, Commander Lawrence B. Cooke, recommended the northward option and Smoot concurred. As Newcomb and Leary turned north, a flurry of shells, Japanese and American, descended on them—Oldendorf’s “big boys” had finally entered the fight.

Standing rearmost in Oldendorf’s line, Admiral Weyler’s battleships had picked up what remained of the Nishimura’s force on their Mark 8 radars at 3:23. The range was 33,000 yards and Weyler held fire. At 3:31, when the Japanese came within 15,600 yards of his cruisers, Oldendorf signaled them to commence firing. Weyler’s battle line, then 22,800 yards from their targets, joined in two minutes later.

grant Falls

Yamashiro’s speed was down to 12 knots when Nishimura ran straight into the fiery, Wagnerian climax he seemed to have been seeking. At 3:52, as a deluge of heavy caliber shells fell on and around his flagship, he sent a final, pathetic message ordering Fuso—which, unknown to him, lay far behind, sinking—to join him at top speed.

Of the six American battleships, only one, Mississippi, had not been temporarily sunk or damaged in the Japanese carrier strike on Pearl Harbor, but their moment of revenge did not amount to much of a contest. West Virginia, leading the line, sent the most shells at its target—93 16-inch armor-piercing rounds. Tennessee, which had participated in 11 operations between its resurrection after Pearl and this action, fired 69 14-inch shells, while her sister, California, fired 63. The other three battlewagons, equipped with the older Mark 3 radar sets, had more trouble. Maryland’s resourceful gun crews ranged in on the splashes from the others and sent six salvoes—a total of 48 16-inch shells—at the Japanese. Pearl veteran Pennsylvania, unable to get a fix on a target, did not fire a shot.

The U.S. Navy battleship USS West Virginia (BB-48) off the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Washington, July 2, 1944, following reconstruction (Naval History and Heritage Command).

Yamashiro, in contrast, had no fire control radar and was shooting at the only targets its crew could see—the destroyers and cruisers. None of its 14-inch shells came near Weyler’s battleships, nor did they even score any hits on a cruiser. Only one Allied ship felt its dying wrath: the unlucky destroyer Albert W. Grant.

As the third ship in Smoot’s Desron 56 column, Grant had launched half of its torpedo complement at 4:03. Then, at 4:07, it took a shell hit. Just as it was about to turn north, more shells struck it. Realizing his ship might be sunk, Grant’s skipper, Commander Terrell A. Nisewaner, ordered all its torpedoes loosed at the enemy.

Still the shells came—a total of seven 4.7-inchers from the flailing Yamashiro’s secondary battery and 11 6-inchers from the American cruiser Denver. A hit on the 40mm gun mount ignited ammunition and started a fire. An explosion on the starboard boat davit killed the ship’s doctor, Lieutenant Charles Akin Mathieu, along with five radiomen and almost the entire amidships repair party. All lights, telephone communications, radars and radios were put out of commission. Resorting to a blinker gun, Nisewaner signaled: “WE ARE DEAD IN THE WATER TOW NEEDED.”

Within the stricken destroyer, First Class Pharmacist’s Mate W.H. Swain Jr. improvised a first-aid dressing station in the head and took on the tasks of physician and surgeon. The chief commissary steward, L.M. Holmes, set up a similar medical station in the wardroom, while sonarman J.C. O’Neill Jr. administered morphine and first aid to grievously wounded shipmates. On Holmes’ wardroom table, Radioman First Class William M. Selleck, who had had both of his legs blown off, uttered last words that none of his shipmates would ever forget: “There’s nothing you can do for me, fellows. Go ahead and do something for those others.”

A warrior’s death

Meanwhile, at 4:09, news of Grant’s situation reached Oldendorf’s flagship and word was relayed to the heavy warships to cease fire. Somehow, Grant stayed afloat. Somehow so did Yamashiro, which even managed to raise 15 knots as it turned hard left and retired southward. Ten minutes later, however, the cumulative punishment of shells and torpedoes caught up with the old dreadnought and Yamashiro capsized, taking all but a few of its crew with it. If Shoji Nishimura could not achieve victory, he gained the other alternative—a warrior’s death.

Cruiser Mogami showed even greater endurance than Yamashiro. Set on fire by an avalanche of 5-inch shells from McManes’ destroyers, it turned south, made smoke and loosed a spread of torpedoes at 4:01. A minute later, an 8-inch salvo from Portland killed Mogami’s captain, his XO and all other officers on the bridge, while also hitting the engines and fireroom and bringing the ship to a dead halt.

At 4:13 Richard P. Leary reported torpedoes passing close by. Admiral Weyler, lying 11,000 yards north of the destroyer, prudently turned away, avoiding Mogami’s last deadly volley, but also taking his battleships out of the fight. Making the most of that reprieve, Mogami’s engineers managed to get it underway again, and it retired southward, joined by Shigure. Meanwhile. Passing through a rain squall, Admiral Shima’s Number Two Striking Force was ambushed at 3:15 off Panaon Island by PT-134, but its torpedoes missed.

At 3:20 Shima ordered a starboard turn so that one of his destroyers could stay clear of Panaon and raised speed to 26 knots. As he did so, however, the destroyer was spotted by Lt. jg Isodore M. Kovar and the crew of PT-137, who launched a torpedo at it. PT-137’s “fish” missed its intended target but, as luck would have it, ran right into the light cruiser Abukuma instead. Badly damaged with 30 crewmen dead and its speed reduced to 10 knots, Abukuma had to drop out of formation. For scoring the most notable success of the PT boats that night, Kovar was awarded the Navy Cross.

At 4:10, as Shima headed north at 28 knots with his two remaining cruisers and four destroyers, he encountered what seemed to be two battleships ablaze in the night—more likely the dying destroyers Asagumo and Michishio. At 4:24, having picked up two southbound ships on his radar screen, he ordered his cruisers to launch torpedoes; they fired erratic spreads of eight apiece. That done, Shima made a quick evaluation based on what little information he had. He recalled his destroyers, which had steamed ahead but still could “see” nothing beyond the smoke laid earlier by the American destroyers. He then sent out a radio dispatch to all Japanese units in the vicinity: “This force has concluded its attack and is retiring from the battle area to plan subsequent action.”

die trying

Just then Mogami emerged from the fog. Nachi’s Captain Enpei Kanooka ordered a change in course to 110 degrees, but he had underestimated Mogami’s speed (he thought it was virtually dead in the water) and the two cruisers collided at 4:30.

Its stern damaged, Shima’s flagship slowed to 18 knots. That settled matters for Shima—he ordered his column to retire, joined by the battered Mogami and Shigure, both miraculously able to keep up in spite of their own damage. At 4:55, Lieutenant Gleason’s PT boats tried to pick off Shigure, but it fought them off, scoring a slightly damaging hit on PT-321.

At the northern end of the strait, Oldendorf learned of the Japanese withdrawal and commenced pursuit. As his flagship, Louisville, headed down the middle of the passageway, he ordered his flank ships to move south and sent a message to Admiral Kincaid: “Enemy cruisers and destroyers are retiring. Strongly recommend an air attack.”

Not all of Oldendorf’s destroyers took part in the chase. Claxton found about 150 Japanese in the water off Bugho Point and lowered a motor whaleboat. Despite an officer who urged his men to avoid capture, three survivors were recovered, including a warrant officer who spoke English and confirmed that his ship, Yamashiro, had gone down. At 5:15, Newcomb and Leary went to assist Albert W. Grant, Newcomb putting its medical officer and two corpsmen aboard the crippled destroyer. At 5:20 Oldendorf’s ships caught up with the slow moving Mogami. Louisville, Portland and Denver immediately engaged it. Several direct hits rekindled Mogami’s fires and Odendorf moved on to seek other prey. Mogami was not quite finished, however, as Lt. jg Harley A. Thronson of PT-491 discovered at 6 a.m., when he found it limping south at 6 knots and tried to trail it—only to come under 8-inch fire that caused his boat to “leap right into the air.” Two torpedoes from PT-491 missed the cruiser, while PT-137 was driven off by its secondary guns. Mogami was not only still full of fight, but had sped up, Kovar reported, to 12 or 14 knots.

Another bellicose cripple was Asagumo, as proved when Cony and Sigourney caught up with it. Those destroyers were having a lively exchange of shellfire when cruisers Denver and Columbia arrived and settled the dispute with their 6-inch guns. A battle-scarred veteran of Java and Guadalcanal, Asagumo died game—its after turret spat defiance even when its decks were awash, and its gunners got off their last parting shot just as its stern went under at 7:21.

an unpredictable retreat

Before any further Japanese units would be overtaken, Oldendorf learned of a shocking new development. Advancing unhindered by Halsey’s Third Fleeet—which was pursuing Ozawa’s decoy carriers—Kurita’s main force had rounded San Bernardino Strait and was engaging the escort carriers, destroyers and destroyer escorts of Carrier Task Unit 77.4.3 (also known as Taffy 3) off Samar Island. Cancelling his pursuit of Shima and recalling all ships involved, Oldendorf and the weary sailors under his command prepared to oppose the new, more serious threat. But then the Battle of Leyte Gulf took one more unexpected turn.

In one of naval history’s epic fighting retreats, Taffy 3 managed to fatally cripple three Japanese heavy cruisers, Suzuya, Chokai and Chikuma, at the cost of the escort carrier Gambier Bay, destroyers Hoel and Johnston and destroyer escort Samuel B. Roberts. Their desperate courage and sacrifice should have done no more than slow Kurita’s advance, but a series of factors had undermined the Japanese admiral’s faith in his own impending victory. Just the day before, he had lost his original flagship and later had seen one of his most powerful battleships, Musashi, sunk by enemy aircraft. The fight now being put up by Taffy 3’s ships and planes caused him to exaggerate their size to fleet, rather than escort, proportions—a perception rendered no better by the fact that his replacement flagship, battleship Yamato, was driven out of the chase in the process of dodging a spread of destroyer torpedoes and was out of touch with the action thereafter. At 9:11 he ordered his ships to break off contact and to “rendezvous, my course north, speed 20.”

Kurita wanted to regroup, assess damage and decide whether to resume his drive into Leyte Gulf. While he was mulling over the matter, at 10:18 he received a radio dispatch from the destroyer Shigure updating him on the situation in Surigao Strait: “All ships except Shigure went down under gunfire and torpedo attack.” That not entirely precise message, together with Shima’s earlier report that he was retiring from the strait and a succession of messages picked up from the Americans, convinced Kurita that powerful naval units were converging on Leyte Gulf. Realizing that if he stormed into Leyte Gulf his force would end up trapped therein, Kurita decided to withdraw at 12:36 p.m.

The loss of more Japanese ships—including all four of Ozawa’s carriers off Cape Engano—was just the anticlimax to a battle already won by the Americans. And worse was still to come. On the morning of October 25, while the Battle of Leyte Gulf was being decided off Samar, aircraft from Rear Admiral Thomas Sprague’s escort carriers were searching for Shima’s retiring force and 17 Eastern Aircraft TMF-1 Avengers finally found it west of the Surigao Peninsula. At 9:10 they attacked the hapless Mogami and left it dead in the water once more—for the last time. Destroyer Akebono evacuated the cruiser’s gallant crew and sent it to the bottom with a torpedo at 12:30 p.m.

At 3 p.m. Shima’s force was subjected to another air attack in the Mindanao Sea, but got through it with only light damage to the destroyer Shiranuhi. Abukuma, its speed down to 9 knots, was in more serious trouble. Shima ordered destroyer Ushio to escort it to Datipan Harbor in Mindanao. Abukuma was still there at 10:06 on the morning of October 26, when the harbor was attacked by 44 North American B-25 Mitchells and Consolidated B-24 Liberators of the Fifth and Thirteenth air forces, operating from Noemfoor and Biak. They scored several hits on their secondary target and started fires that reached Abukuma’s torpedo room. The explosion that followed blew a large hole in the light cruiser, which sank southwest of Negros Island at 12:42.

Shima’s flagship, Nachi, became a last, belated fatality of the Battle of Surigao Strait. Taking shelter in Manila Bay, it was attacked and sunk there on November 5 by Avengers and Helldivers from the carrier Lexington.

“never give a sucker a chance”

In retrospect, it is easy to dismiss Surigao Strait as a relatively minor element of the epic Battle of Leyte Gulf. Its principal place in history has been a sentimental one—the fight in which the resurrected “ghosts of Pearl Harbor” returned to haunt the Japanese, as well as the last time a line of battleships would ever “cross the T” on an approaching enemy.

Even had they combined, the two Japanese units that entered the strait were outnumbered, outgunned and outmaneuvered. Although their crews performed with outstanding courage and ingenuity, the only competent judgment displayed by their commanders was Shima’s decision to withdraw. Their one chance had been the possibility that their American opponents would commit a major error. But aside from Denver’s and Columbia’s ill-chosen bombardment of Albert W. Grant, neither Jesse Oldendorf nor his subordinates made any serious mistakes that night. The overall performance of his destroyer units was brilliant, almost depriving the big-gun ships any targets. With the added benefit of superior intelligence, courtesy of his PT boats and radar, Oldendorf knew he would win and devoted himself to achieving that victory with minimal casualties. As he put it shortly after the battle: “My theory was that of the old-tie gambler: Never give a sucker a chance. If my opponent is foolish enough to come at me with an inferior force, I’m certainly not going to give him an even break.”

The result was truly a lopsided victory—two Japanese battleships, a cruiser and three destroyers sunk, along with thousands of Japanese casualties, all at the price of one PT boat, 39 American sailors and airmen killed, and 114 wounded. Nishimura and Shima may not have represented the greatest threat to the beachhead at Leyte, but their elimination was significant enough to the invading U.S. Army troops, who they would otherwise have been bombarding. It may be argued, too, that the greatest contribution that Surigao Strait made to the victory at Leyte Gulf was its effect on the uncertain mind of Admiral Kurita off Samar.

For further reading: Leyte Gulf, by Mark E. Stille, Bryan Cooper’s PT Boats, Samuel Eliot Morison’s History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol.XII, Leyte; and Theodore Roscoe’s Tin Cans.