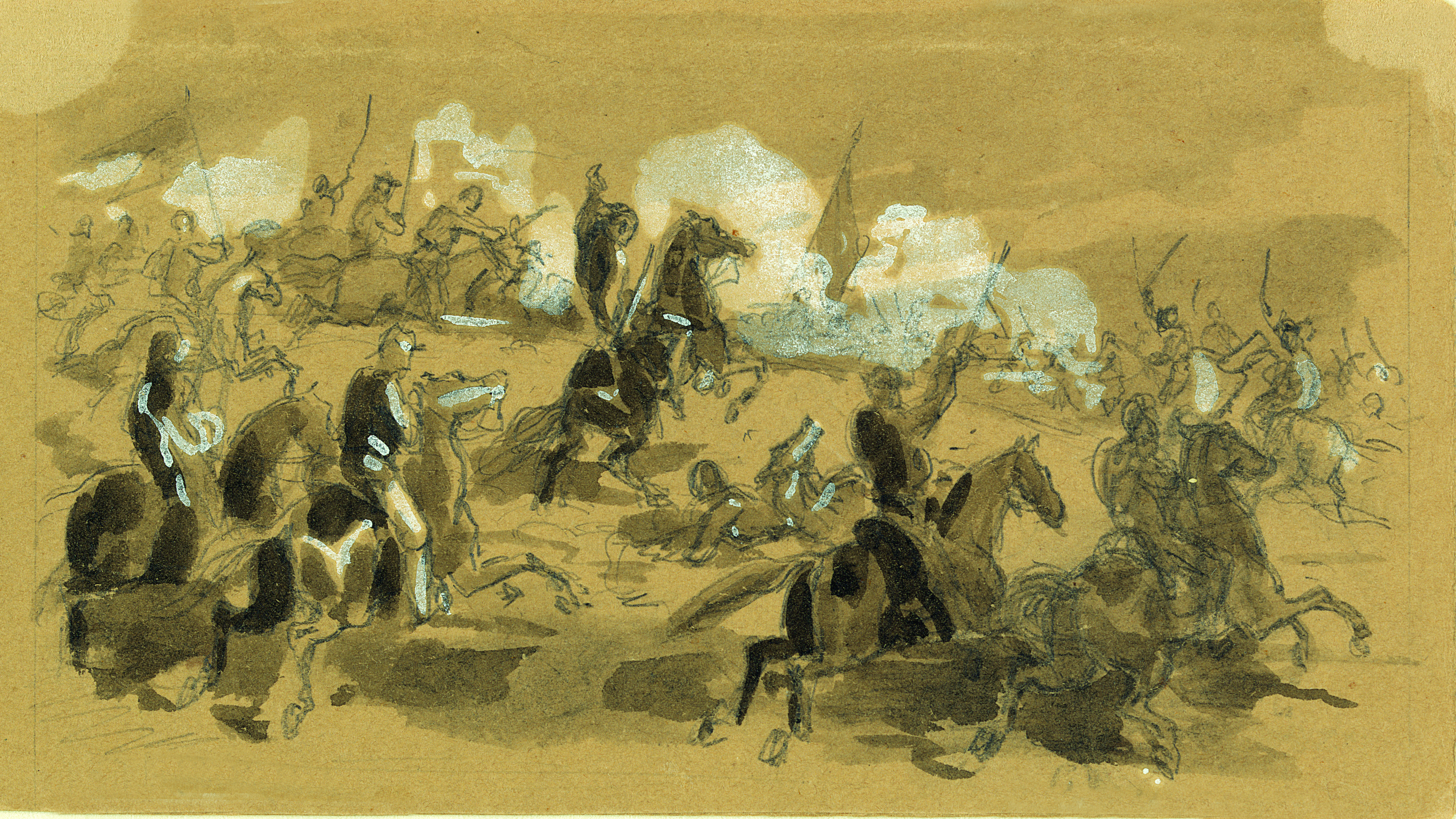

Much-maligned Yankee cavalry finally got the best of its Confederate rivals

Confederate troops used key railroads such as the Orange & Alexandria to move about Virginia. By November 1862, when Alfred Waud sketched

this Union O&A picket post, Yankee forces had control of several tracks.

BY THE SUMMER OF 1862, Federal Brig. Gen. John P. Hatch and his brigade of horse soldiers were already seasoned veterans, having seen plenty of action on the short end of Stonewall Jackson’s legendary Shenandoah Valley Campaign earlier in the year. On June 26, in an effort to revive flagging Union prospects in the Eastern Theater, President Abraham Lincoln formed the Army of Virginia under Maj. Gen. John Pope. Lincoln desperately hoped that the pompous Pope, victor of several recent battles in Tennessee and Missouri, could crush Stonewall’s vaunted army once and for all.

Hatch’s cavalry, which consisted of the 1st Michigan, 5th New York, 1st Virginia (redesignated the 1st West Virginia when that state joined the Union in 1863), and 1st Vermont, was added to Pope’s ranks. The change of commander, however, did not improve Hatch’s fortunes. Assigned to destroy a portion of the Virginia Central Railroad, he and his troopers headed from Culpeper, Va., to the station town of Gordonsville on July 17, only to get beaten to the town by Confederate infantry by proceeding at a ponderous pace. Although Hatch’s brigade had been accompanied on its march by infantry and artillery, the general decided not to face the Southerners when he reached Gordonsville and withdrew.

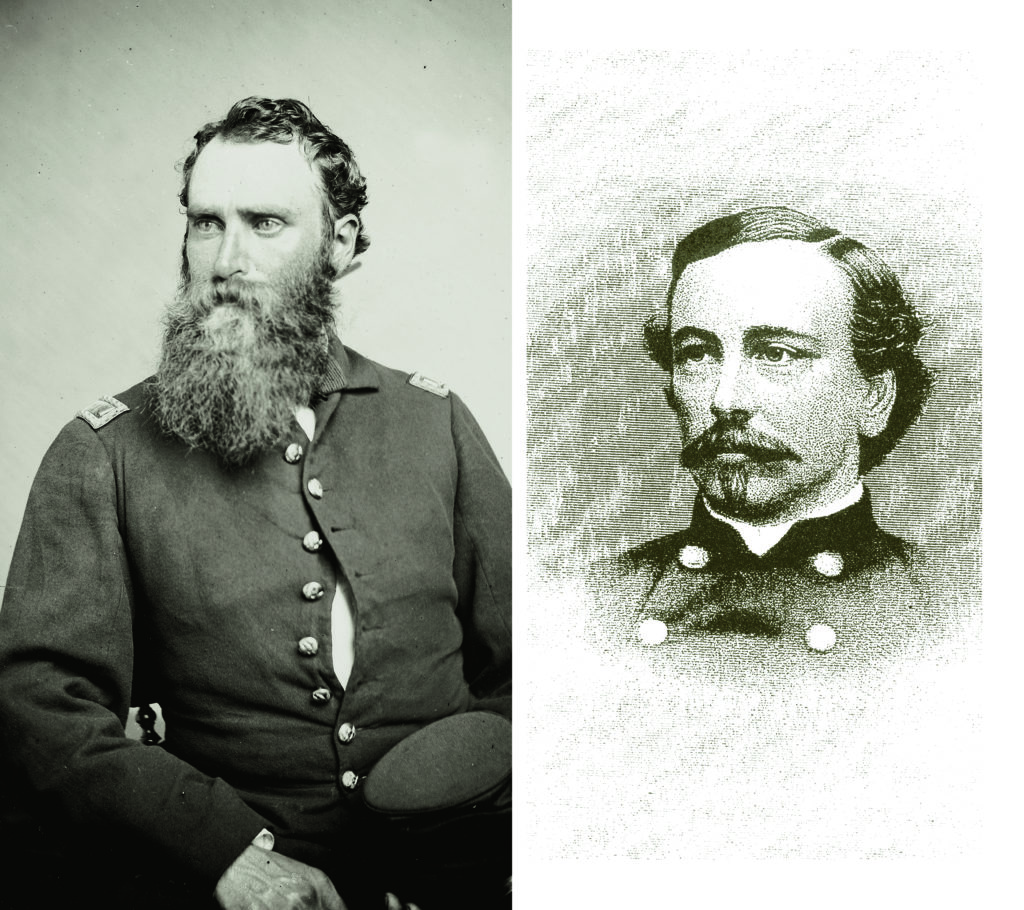

After Hatch failed in a second attempt to wreck the railroad the following week—blaming the fiasco on “the utter breaking up of the horses, the state of the roads, and…storms”—he was finally relieved by a disgusted Pope. Nearly a year later, Hatch’s replacement, John Buford, would become immortal for his resolute stand on McPherson’s Ridge on the first day at Gettysburg. But for now, Pope needed anyone he could count on. Buford, a career cavalryman with respectable enough credentials, had been languishing in the Army’s inspector general’s office in Washington, D.C. Pope promoted him to brigadier general on July 27, and sent him to Central Virginia.

For a few days, as Buford traveled, Colonel Thornton F. Brodhead led the brigade. The brigadier didn’t reach his command until August 3, but before long, it became clear he was a worthy substitute for Hatch.

On August 2, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks, head of the Army of Virginia’s 2nd Corps, ordered Brig. Gen. Samuel W. Crawford, one of his 1st Division brigade commanders, to lead a mixed force of infantry and cavalry on a reconnaissance-in-force toward the town of Orange Court House, 19 miles south of Culpeper. Crawford was to locate not only Stonewall Jackson’s army but also to learn the makeup of the Confederate forces in front of Banks.

With Buford’s brigade attached—Brodhead in command—the Federal column moved out at 4 a.m. Thinned by heavy casualties to men and horses, the brigade now consisted of only about 1,000 troopers.

The Federals crossed the Rapidan River below Culpeper and marched along the south bank of the river. Brodhead’s troopers were forced to navigate Crooked Run and the Robinson River but covered several miles en route to the Orange county seat of Orange Court House. Leading the way were Colonel Othniel DeForest’s 5th New York and Colonel Charles H. Tompkins’ 1st Vermont.

Arriving at the junction of the Rapidan Station Road and the Old Turnpike (Fredericksburg Road), Tompkins ordered Captain Henry Flint, with a squadron of the 1st Vermont (Companies H and I) and a squadron of the 5th New York, commanded by Major William P. Pratt, to deploy as skirmishers. Those skirmishers came upon 50 or so pickets of the 17th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry. Drawing their sabers, they charged, scattering the Confederate pickets—killing one and wounding another—before advancing into Orange Court House. Recalled a 5th New York trooper: “Without opposition, the advance entered the town, whose streets they found deserted, while a stillness like that of death seemed to reign all around.”

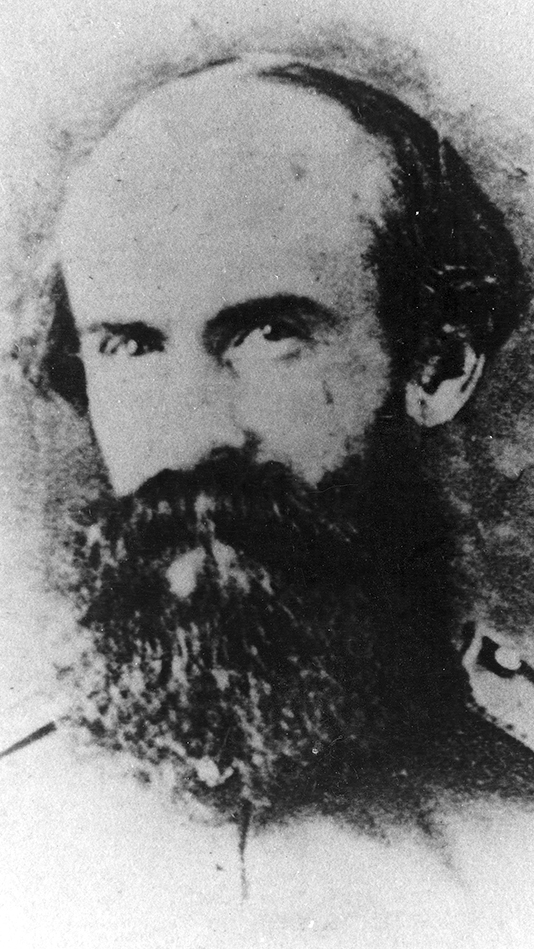

Not long after that encounter, the 7th Virginia Cavalry arrived to reinforce the 17th Battalion’s pickets. When Brig. Gen. Beverly H. Robertson spotted a lone Yankee ahead, he ordered the 7th to support his brigade’s pickets along the Rapidan Road, saying, “Boys, that Yankee is not alone; there may be a troop down there.” Colonel William E. “Grumble” Jones, the 7th’s cantankerous but highly competent commander, learned from the pickets who had just been chased away that there was indeed a large enemy force advancing on the town. “No time could be afforded for inquiries[;] to fight or run were the only alternatives,” Jones declared. “I chose the former, and, as it turned out, against immense odds.”

The colonel deployed some of his men as dismounted sharpshooters, while the rest prepared for a mounted charge. Major Thomas C. Marshall, Jones’ second-in-command, took part of the 7th Virginia and tried to outflank the Federals near the Orange & Alexandria Railroad’s downtown depot, while Jones led the rest of the regiment in a charge at the main enemy body. “The main street of Orange Court House was packed with the contending horsemen,” recalled a Confederate officer, “the choice spirits of both sides pushing into the thick of the fight, the timid withdrawing.”

Noted Colonel Tompkins: “[T]he front of the column becoming confused created some disorder in the main body. The confused troops were gotten out of the way and order restored and the companies reformed.” Once the muddled troopers were out of the way, Captains Hiram Hall and William Wells of the 1st Vermont led a determined countercharge. Wells and his company drew their sabers and prepared to charge. Hall, seeing that Wells would support him, cried “Charge!” The Vermonters bolted ahead “with a yell and the rebels broke and fled in every direction, and we after them, running them down and taking them prisoners,” wrote Sergeant Homer Ruggles of Hall’s company.

Wells, who later received the Medal of Honor for his performance at Gettysburg and ended the Civil War as a brevet major general, recounted, “Co. F & C were called upon to charge with Sabre which they did and drove the Rebels like chaff before the wind, out of town, a few of us went out about ¾ miles out of town. I was one of them.”

They pursued the Confederates through a barnyard and along a farm lane into a ditch. Wells eventually turned his command around and headed back, fortunately dodging capture along the way. “The fact is we went a little too far with so small a force & had to run our horses as fast as they would go to Keep them out of their hands,” wrote Wells, who also noted, “the boys behaved nobly.”

Meanwhile, another column of Union cavalry crashed into Jones’ right and rear. Lieutenants Jacob G. Neff and Jacob Mohler of the 7th Virginia responded by wheeling their horses around and charging the Federals with about a dozen troopers in tow. Mohler and Neff, who was wounded in this exchange, were able to blunt the Union charge, driving the rear Union companies off while wounding or capturing several Federals.

Jones found himself separated from his men and surrounded by Yankees. Fortunately, as an expert swordsman, he hacked his way to safety. Union cavalry, however, successfully drove the Confederates out of Orange and beyond.

“Shots flew in every direction, killing horses and men alike,” remembered a member of the 5th New York. “The fight was furious in the narrow streets.” Captain John Hammond of Crown Point, N.Y., commanded a company of the Empire State regiment. Seeing an opportunity, he ordered his men “to draw sabers, and told them that it was the first time we had had a good chance to use them, and that we would carry the place or die if they used their hardware well.” With a cheer, Hammond’s company did as instructed and crashed into Marshall’s flank, hurling it back. “And they did the work most heroically,” recalled the 5th New York’s regimental historian. “Tremendous were the blows they dealt, and the street was strewn with unhorsed men whose head [sic] displayed fearful gashes from the Yankee sabers.”

The poorly mounted Marshall fell behind, his horse unable to keep up. The major had emptied his pistols during the initial charge—left with no other viable weapon, he drew his saber and attempted to slash his way out, only to be knocked senseless by a Yankee saber. At the Federals’ mercy, Marshall might have been killed, if not for Jones, who arrived at the head of his column and shot down a Federal trooper on the verge of dealing the stunned major a lethal saber blow. Nevertheless, there were still too many Union horsemen and Marshall remained a prisoner.

“The Yankees were bearing down on us not fifty yards away at a fast trot, firing their revolvers as they came [and] a few men and a few horses were struck,” wrote Lieutenant John Blue, riding with the 7th Virginia that day. “Most of their shots were passing over our heads.”

“There arose that terrible Rebel yell,” Blue added, “and with drawn sabre at a tierce point and rowels buried deep in our horses’ flanks, at them we went at full speed, when we met the blue and the gray was considerably mixed for a few moments.” (“Tierce point,” a French term in fencing and swordsmanship that 19th-century readers would surely have recognized, means a saber held at extended arm’s length during a charge.)

Hammond, who ended the war as a colonel and brevet brigadier general, later claimed with justification: “I believe that myself and command have the credit of taking the place, while our main body was repulsed….Our men fought like devils and yelled like savages. We charged, with sabre in hand, with such impetuosity that we swept everything before us. The bullets flew about us like hail, but our brave boys were irresistible.”

As a fellow Empire Stater later noted, Lieutenant James Penfield of the 5th New York, “with a thorough knowledge of sabre exercise, with a long, strong arm, and a courageous heart, did terrible execution in this fray.” During the melee, however, the 5th’s commander, Colonel DeForest, was nearly captured by one of Jones’ men—saved from such humiliation by a bugler.

“It soon became evident that the weight of numbers was forcing us back,” observed Blue, realizing that the Confederates had been beaten by these aggressive Union troopers. “We were overmatched in the mix….Our men had given back faster and the Yankees on that side were forging past us….We kept backing and defending ourselves the best we knew how….The truth is we were hemmed in by a whole brigade. Outnumbered at least five to one. Overpowered and very much demoralized.”

Despite the odds against him, Jones lamented a missed opportunity.

“The enemy here was only checked, and on the renewal of the attack [our] rear companies fled up the plank road before inferior numbers,” he recounted. “A broken culvert and bridge caused them a heavy loss. Had these men joined the fight boldly, a glorious victory would most surely have been ours….[F]our companies (A, B, C, and D), after driving the enemy from the town, found themselves confronted with such overwhelming odds as necessitated a retreat.”

The badly beaten Virginians fled to the Willis Mansion south of town to regroup and await reinforcements, with only a feeble effort at pursuit by the victorious Federals, who then retreated into the town. “Feeling myself greatly outnumbered, I withdrew to a suitable point of observation, about a mile this [side] of the town,” Jones concluded.

About an hour later, the Union cavalrymen withdrew from Orange Court House, pulling back a mile or so to find Crawford waiting for them. Having accomplished their goal, the Federal troopers eventually headed toward Culpeper, much to the disappointment of Jones, who by then had received reinforcements from the 6th Virginia Cavalry and wanted to renew the contest.

Reported Colonel Tompkins: “During the entire skirmish, 25 of the enemy were killed, 2 mortally and several severely wounded, and 52 taken prisoners.” But, Jones claimed, “From the best information attainable the loss of the enemy was 11 men and 12 horses killed; their wounded must have been 30 and their missing was 12,” adding that his “casualties and missing nearly equal to that of the enemy.”

Jones, however, had gone into battle with about 200 officers and men; the Yankees had at least twice as many engaged.

Orange Court House marked several firsts. It marked the first of very few instances of mounted urban cavalry fighting in the Civil War—the others were the June 28, 1863, Battle of Westminster (Corbit’s Charge) and the June 30, 1863, Battle of Hanover, Pa., both during the Gettysburg Campaign; the July 6, 1863, Battle of Hagerstown, Md., during Lee’s Retreat from Gettysburg; and the February 11, 1865, Battle of Aiken, S.C., in the war’s waning days. It also marked an important step in the maturation of the Union cavalry. “This engagement clearly proved our superiority over the enemy’s cavalry,” declared a 5th New York trooper, “which, in this instance, consisted of their best Virginia regiments lately under Col. [Turner] Ashby.”

While that overstated the case, it also foreshadowed the day—not far off—when the Union cavalry would often equal or best its Confederate counterparts in battle. The Yankees would suffer two humiliating defeats in Virginia before the end of the month, routed at Cedar Mountain one week after the Orange Court House clash, and then at Second Manassas on August 28-30. The Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863, is generally accepted as the date that the Union cavalry finally established itself as the equal of its much-vaunted opponent. But what Federal troopers achieved at Orange Court House should not be discounted.

Eric J. Wittenberg, an award-winning historian, is the author of several Civil War titles, including (with Daniel T. Davis) Out Flew the Sabres: The Battle of Brandy Station.

_____

7th Virginia Cavalry’s Shenandoah roots

Colonel Angus W. McDonald recruited Shenandoah Valley men to fill the ranks of the 7th Virginia Cavalry in 1861. The regiment soon became known as “Ashby’s Cavalry” in recognition of Brig. Gen. Turner Ashby, who was killed in combat June 6, 1862, at Good’s Farm near

rrisonburg, Va., during Stonewall Jackson’s Spring 1862 Valley Campaign. By the time of Ashby’s death, the regiment comprised an unwieldy 29 companies. After Ashby’s death, the first 10 companies remained as the 7th Virginia Cavalry—the remaining companies became the nucleus of the 12th Virginia Cavalry and the 17th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry. Colonel William E. “Grumble” Jones assumed command of the regiment on July 18, 1862, after briefly serving as colonel of the 1st Virginia Cavalry. Jones was a difficult personality—his nickname was well-earned—but he was a capable, professional cavalryman. The cavalry clash August 2, 1862, at Orange Court House marked the first of the 7th Virginia’s battlefield encounters. Jones had about 200 officers and men with him that day. –E.J.W.

This story appeared in the January 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.